Coral Reef Degradation in the Indian Ocean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Host Population Genetics and Biogeography Structure the Microbiome of the Sponge Cliona Delitrix

Received: 11 October 2019 | Revised: 20 December 2019 | Accepted: 23 December 2019 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.6033 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Host population genetics and biogeography structure the microbiome of the sponge Cliona delitrix Cole G. Easson1,2 | Andia Chaves-Fonnegra3 | Robert W. Thacker4 | Jose V. Lopez2 1Department of Biology, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN Abstract 2Halmos College of Natural Sciences Sponges occur across diverse marine biomes and host internal microbial communities and Oceanography, Nova Southeastern that can provide critical ecological functions. While strong patterns of host specific- University, Dania Beach, FL 3Harriet L. Wilkes Honors College, Harbor ity have been observed consistently in sponge microbiomes, the precise ecological Branch Oceanographic Institute, Florida relationships between hosts and their symbiotic microbial communities remain to be Atlantic University, Fort Pierce, FL fully delineated. In the current study, we investigate the relative roles of host popu- 4Department of Ecology and Evolution, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY lation genetics and biogeography in structuring the microbial communities hosted by the excavating sponge Cliona delitrix. A total of 53 samples, previously used to Correspondence Cole G. Easson, Department of Biology, demarcate the population genetic structure of C. delitrix, were selected from two lo- Middle Tennessee State University, cations in the Caribbean Sea and from eight locations across the reefs of Florida and Murfreesboro, TN 37132, USA. Email: [email protected] the Bahamas. Microbial community diversity and composition were measured using Illumina-based high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA V4 region and related to Funding information Division of Ocean Sciences, Grant/ host population structure and geographic distribution. -

Lab Essentials Best-Selling Supplies and Equipment

Get What You Need Now! See page 1 for details Lab Essentials Best-selling supplies and equipment Fluid Transfer Lab Equipment Products to help you collect, prepare , and analyze your Consumables & Supplies samples 1-800-363-5900 Find >100,000 products Expert product assistance at ColeParmer.ca Felesha, Application Specialist At Cole-Parmer, you come first. We’ve been in the Cole-Parmer: industry more than 60 years, so we understand your expectations and challenges. That’s why you will only experts in science, find industry-leading brands you can trust, backed by a team of application experts who will work with you to dedicated to your meet your requirements. Consider us part of your team. We are dedicated to being your source for fluid handling success products, instrumentation, equipment, and supplies. Your 100% satisfaction is our number one goal. We look forward to helping you succeed. Have questions? We have answers. Our team of highly-trained technical specialists has more than 150 years of experience solving the most demanding customer applications. We will work with you on product selection, troubleshooting, regulatory compliance, or maintenance and repair. With expertise across scientific and industrial disciplines, we will help you achieve the highest performance and cost effectiveness for your project. Call, email, or live chat today to put us to work for you. 1-800-363-5900 ColeParmer.ca [email protected] Go to ColeParmer.ca/Terms for a full list of terms and conditions. For full information on returns, go to ColeParmer.ca/returns. ©2017 Cole-Parmer Instrument Company, LLC. All rights reserved. -

Status of Alcyonacean Corals Along Tuticorin Coast of Gulf of Mannar, Southeastern India

Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences Vol. 43(4), April 2014, pp. 666-675 Status of Alcyonacean corals along Tuticorin coast of Gulf of Mannar, Southeastern India S. Rajesh, K. Diraviya Raj, G. Mathews, T. Sivaramakrishnan & J.K. Patterson Edward Suganthi Devadason Marine Research Institute 44-Beach Road, Tuticorin – 628 001, Tamil Nadu, India [E-mail: [email protected]] Received 28 November 2012; revised 7 December 2012 In this study, the assessment of alcyonaceans was conducted in Tuticorin coast of the Gulf of Mannar during the period between 2010 and 2012 in 5 locations; Vaan, Koswari, Kariyachalli and Vilanguchalli islands and mainland Punnakayal patch reef. Average alcyonacean coral cover in Tuticorin coast was 6.76% during 2011-12 which was 5.61% during 2010- 2011. Percentage cover of alcyonacean corals increased in all the study locations; Kariyachalli 12.04 to 13.96%; Vilanguchalli 8.94 to 10.23%; Koswari 1.6 to 3.69; Vaan 0.53 to 0.72; mainland Punnakayal patch reef 4.95 to 5.21% was documented. In total, 15 species from 7 genera were recorded during the study period. Though anthropogenic threats in Tuticorin coast are comparatively high, the abundance of alcyonacean corals has increased considerably showing their resilience and adaptability. [Keywords: Alcyonacean corals, Status, Diversity, Tuticorin, Gulf of Mannar] Introduction experience all the natural and anthropogenic threats. Alcyonacean corals (soft corals and gorgonians) Reef ecosystems of Gulf of Mannar are heavily are modular cnidarians composed of polyps that stressed due to various human induced threats like always have eight tentacles and are oftentimes destructive and over fishing practices, coral mining, connected by vessels classified under subclass domestic and industrial pollution, seaweed and other Octocorallia while hard corals have six tentacles resource collection in reef areas and invasion of (which are hexa corals). -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

Satellite Monitoring of Coastal Marine Ecosystems a Case from the Dominican Republic

Satellite Monitoring of Coastal Marine Ecosystems: A Case from the Dominican Republic Item Type Report Authors Stoffle, Richard W.; Halmo, David Publisher University of Arizona Download date 04/10/2021 02:16:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/272833 SATELLITE MONITORING OF COASTAL MARINE ECOSYSTEMS A CASE FROM THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Edited By Richard W. Stoffle David B. Halmo Submitted To CIESIN Consortium for International Earth Science Information Network Saginaw, Michigan Submitted From University of Arizona Environmental Research Institute of Michigan (ERIM) University of Michigan East Carolina University December, 1991 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables vi List of Figures vii List of Viewgraphs viii Acknowledgments ix CHAPTER ONE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 The Human Dimensions of Global Change 1 Global Change Research 3 Global Change Theory 4 Application of Global Change Information 4 CIESIN And Pilot Research 5 The Dominican Republic Pilot Project 5 The Site 5 The Research Team 7 Key Findings 7 CAPÍTULO UNO RESUMEN GENERAL 9 Las Dimensiones Humanas en el Cambio Global 9 La Investigación del Cambio Global 11 Teoría del Cambio Global 12 Aplicaciones de la Información del Cambio Global 13 CIESIN y la Investigación Piloto 13 El Proyecto Piloto en la República Dominicana 14 El Lugar 14 El Equipo de Investigación 15 Principales Resultados 15 CHAPTER TWO REMOTE SENSING APPLICATIONS IN THE COASTAL ZONE 17 Coastal Surveys with Remote Sensing 17 A Human Analogy 18 Remote Sensing Data 19 Aerial Photography 19 Landsat Data 20 GPS Data 22 Sonar -

Taxonomic Checklist of CITES Listed Coral Species Part II

CoP16 Doc. 43.1 (Rev. 1) Annex 5.2 (English only / Únicamente en inglés / Seulement en anglais) Taxonomic Checklist of CITES listed Coral Species Part II CORAL SPECIES AND SYNONYMS CURRENTLY RECOGNIZED IN THE UNEP‐WCMC DATABASE 1. Scleractinia families Family Name Accepted Name Species Author Nomenclature Reference Synonyms ACROPORIDAE Acropora abrolhosensis Veron, 1985 Veron (2000) Madrepora crassa Milne Edwards & Haime, 1860; ACROPORIDAE Acropora abrotanoides (Lamarck, 1816) Veron (2000) Madrepora abrotanoides Lamarck, 1816; Acropora mangarevensis Vaughan, 1906 ACROPORIDAE Acropora aculeus (Dana, 1846) Veron (2000) Madrepora aculeus Dana, 1846 Madrepora acuminata Verrill, 1864; Madrepora diffusa ACROPORIDAE Acropora acuminata (Verrill, 1864) Veron (2000) Verrill, 1864; Acropora diffusa (Verrill, 1864); Madrepora nigra Brook, 1892 ACROPORIDAE Acropora akajimensis Veron, 1990 Veron (2000) Madrepora coronata Brook, 1892; Madrepora ACROPORIDAE Acropora anthocercis (Brook, 1893) Veron (2000) anthocercis Brook, 1893 ACROPORIDAE Acropora arabensis Hodgson & Carpenter, 1995 Veron (2000) Madrepora aspera Dana, 1846; Acropora cribripora (Dana, 1846); Madrepora cribripora Dana, 1846; Acropora manni (Quelch, 1886); Madrepora manni ACROPORIDAE Acropora aspera (Dana, 1846) Veron (2000) Quelch, 1886; Acropora hebes (Dana, 1846); Madrepora hebes Dana, 1846; Acropora yaeyamaensis Eguchi & Shirai, 1977 ACROPORIDAE Acropora austera (Dana, 1846) Veron (2000) Madrepora austera Dana, 1846 ACROPORIDAE Acropora awi Wallace & Wolstenholme, 1998 Veron (2000) ACROPORIDAE Acropora azurea Veron & Wallace, 1984 Veron (2000) ACROPORIDAE Acropora batunai Wallace, 1997 Veron (2000) ACROPORIDAE Acropora bifurcata Nemenzo, 1971 Veron (2000) ACROPORIDAE Acropora branchi Riegl, 1995 Veron (2000) Madrepora brueggemanni Brook, 1891; Isopora ACROPORIDAE Acropora brueggemanni (Brook, 1891) Veron (2000) brueggemanni (Brook, 1891) ACROPORIDAE Acropora bushyensis Veron & Wallace, 1984 Veron (2000) Acropora fasciculare Latypov, 1992 ACROPORIDAE Acropora cardenae Wells, 1985 Veron (2000) CoP16 Doc. -

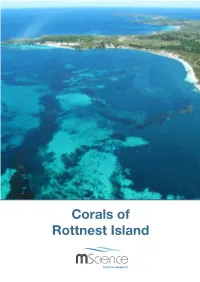

Corals of Rottnest Island Mscience Pty Ltd June 2012 Volume 1, Issue 1

Corals of Rottnest Island MScience Pty Ltd June 2012 Volume 1, Issue 1 MARINE RESEARCH Produced with the Assistance of the Rottnest Island Authority Cover picture courtesy of H. Shortland Jones * Several of the images in this publication are not from Rottnest and were sourced from corals.aims.gov.au courtesy of Dr JEN Veron Contents What are hard corals? ...........................................................................................4 Corals at Rottnest Island .....................................................................................5 Coral Identification .............................................................................................5 Hard corals found at Rottnest Island ...............................................................6 Faviidae ............................................................................................................7 Acroporidae and Pocilloporidae ....................................................................11 Dendrophyllidae ............................................................................................13 Mussidae ......................................................................................................15 Poritidae .......................................................................................................17 Siderastreidae ..............................................................................................19 Coral Identification using a customised key ................................................21 Terms used -

Temperature Data Logger (Dl2b) User Manual

TEMPERATURE DATA LOGGER (DL2B) USER MANUAL Features Data logger simultaneously displays minimum, maximum and current temperatures The unit will provide a visual and audio alert when temperature rises above or falls below the high and low set points. The min/max feature is designed to monitor and store the highest and lowest readings until the memory is cleared, or removal of battery. The temperature sensor is enclosed in a glycol-filled bottle, protecting it from rapid temperature changes when refrigerator/freezer door is opened. Low battery alert function ( battery symbol flashes) User can select oC or oF temperature display Measuring temperature range -45 ~ 120 oC ( or -49 ~ 248 oF) Operating conditions: -10 ~ 60 oC ( or -50 ~ 140 oF) and 20% to 90% non-condensing (relative humidity) Accuracy : ± 0.5 oC (-10 ~ 10 oC or 14 ~ 50 oF), in other range ± 1 oC ( or ± 2 oF) User defined logging interval 1 6.5 ft (2 meters) NTC probe-connecting cable Rechargeable Li-ion battery to record data up to 8 hours during a power-failure event Powered by a 12VDC power adapter Compatible with a USB 3.0 Extension Cable for durability and easy data transfer Large LED lit LCD screen Dimensions:137mm(L)×76mm(W)×40mm(D) Mounting hole dimension: 71.5mm(W) x 133mm(L) Felix Storch, Inc. │ Bronx, NY 10474│ Tel: (718) 893-3900│ Fax: (844) 478-8799 SAVE THIS MANUAL FOR FUTURE REFERENCE AccuCold, Div of Felix Storch, Inc. | R005-07102018 READ ALL INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE USE Package Contents . Data logger . Instructions manual . 4 GB Memory stick [FAT 32] . -

(Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, for the Year 2009

REPORT U/s 21 (4) OF THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989, FOR THE YEAR 2009 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE NO. NO. 1 INTRODUCTION 1-4 2 STRUCTURE AND MECHANISM ESTABLISHED FOR 5-9 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989. 3 ACTION BY THE POLICE AND THE COURTS IN CASES 10-14 REGISTERED UNDER THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989. 4. MEASURES TAKEN BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 15-19 5. MEASURES TAKEN BY STATE GOVERNMENTS AND UNION 20-87 TERRITORY ADMINISTRATIONS STATE GOVERNMENTS 5.1 ANDHRA PRADESH 20-27 5.2 ARUNACHAL PRADESH 28 5.3 ASSAM 29-30 5.4 BIHAR 31-33 5.5 CHHATTISGARH 35-36 5.6 GOA 37-38 5.7 GUJARAT 39-42 5.8 HARYANA 43-44 5.9. HIMACHAL PRADESH 45-46 5.10 KARNATAKA 47-49 5.11 KERALA 50-51 5.12 MADHYA PRADESH 52-56 5.13 MAHARASHTRA 57-60 5.14 MANIPUR 61 5.15 ODISHA 62-64 5.16 PUNJAB 65-66 5.17 RAJASTHAN 67-69 5.18 SIKKIM 70-71 5.19 TAMIL NADU 72-75 5.20 TRIPURA 76 5.21 UTTAR PRADESH 77-78 5.22 WEST BENGAL 79-80 UNION TERRITORY ADMINISTRATIONS 5.23 ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS 81 5.24 CHANDIGARH 82 5.25 DAMAN & DIU 83 5.26 NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI 84 5.27 LAKSHADWEEP 85 5.28 PUDUCHERRY 86 5.29 OTHER STATE GOVERNMENTS/UNION TERRITORY 87 ADMINISTRATIONS ANNEXURES I EXTRACT OF SECTION 3 OF THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND 88-90 THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989. -

Alosi, Marlena C., Analysis of Efficiency and User Satisfaction Following The

Alosi, Marlena C., Analysis of Efficiency and User Satisfaction Following the Introduction of Digital Source Documents and Resources in a Clinical Research Setting. Master of Science (Clinical Research Management), November 2015, 111p., 2 tables, 17 figures, reference list of 23 sources. Efficient and accurate data management processes are essential for the successful conduction of clinical trials. The clinical research industry is unique among biomedical fields in that much of the reporting is still conducted using paper-based systems. Recent trends towards exchanging paper-based documentation methods for electronic documentation methods have shown that implementation of digital resources have the potential to expedite clinical development. This practicum sought to evaluate paper-based and electronic documentation processes in a cancer clinic in regards to efficiency and user satisfaction, and determine which documentation form was superior in these areas. Retrospective analyses and a survey were used as the sources of data to assess for these differences. It was determined that the replacement of paper-based methods with electronic methods of documentation at this particular clinic resulted in both greater timeliness and higher user satisfaction. ANALYSIS OF EFFICIENCY AND USER SATISFACTION FOLLOWING THE INTRODUCTION OF DIGITAL SOURCE DOCUMENTS AND RESOURCES IN A CLINICAL RESEARCH SETTING Marlena C. Alosi, B.S. APPROVED BY: _______________________________________________________________________ Lad Dory, Ph.D., FAHA, Major Professor -

EXTENDED COST BENEFIT ANALYSIS of PRESENT and FUTURE USE of INDONESIAN CORAL REEFS an Empirical Approach to Sustainable Management of Tropical Marine Resources

Aus dem Institut für Agrarökonomie der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel EXTENDED COST BENEFIT ANALYSIS OF PRESENT AND FUTURE USE OF INDONESIAN CORAL REEFS An Empirical Approach to Sustainable Management of Tropical Marine Resources Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Agrar-und Ernährungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Magister of Science Achmad Fahrudin aus Jakarta (Indonesien) Kiel, November 2003 Dekan : Prof. Dr. Friedhelm Taube Erster Berichterstatter : Prof. Dr. Christian Noell Zweiter Berichterstatter : Prof. Dr. Franciscus Colijn Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 06.11.2003 i Gedruckt mit Genehmigung der Agrar- und Ernährungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel ii Zusammenfassung Korallen stellen einen wichtigen Faktor der indonesischen Wirtschaft dar. Im Vergleich zu anderen Ländern weisen die Korallenriffe Indonesiens die höchsten Schädigungen auf. Das zerstörende Fischen ist ein Hauptgrund für die Degradation der Korallenriffe in Indonesien, so dass das Gesamtsystem dieser Fangpraxis analysiert werden muss. Dazu wurden im Rahmen dieser Studie die Standortbedingungen der Korallen erfasst, die Hauptnutzungen mit ihren jeweiligen Auswirkungen und typischen Merkmale der Nutzungen bestimmt sowie die politische Haltung der gegenwärtigen Regierung gegenüber diesem Problemfeld untersucht. Die Feldarbeit wurde in der Zeit von März 2001 bis März 2002 an den Korallenstandorten Seribu Islands (Jakarta), Menjangan Island (Bali) und Gili Islands -

Full Text in Pdf Format

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 152: 227-239, 1997 Published June 26 Mar Ecol Prog Ser 1 Habitat specialisation and the distribution and abundance of coral-dwelling gobies Philip L. Munday*, Geoffrey P. Jones, M. Julian Caley Department of Marine Biology, James Cook University of North Queensland. Townsville, Queensland 4811, Australia ABSTRACT Many fishes on coral reefs are known to associate with particula~microhabitats If these associations help determine population dynamics then we would expect (1) a close assoclation between the abundances of these fishes and the abundances of the most frequently used mlcrohabitats and (2) changes in the abundance of microhabitats would result in a corresponding change In fish population sizes We examined habitat associations among obligate coral-dwelling gob~es(genus Goblodon) and then investigated relationships between the spatial and temporal ava~labilltyof habitats and the abundances of Goblodon species among locations and anlong zoncs on the leef at Lizard Island (Great Barrler Reef) Out of a total of 11 Acropora species found to be used by Gobiodon, each specic3s of Goblodon occupied 1 01 2 species of Acropora significantly more often than expected from the avail- ability of these corals on the reef Across reef zones, the abundance of most species of Gobiodon was closely correlated with the abundance of coral species most frequently inhabited However, the abun- dance of 1 species G ax~llar~s.iiras not conelated with the availability of most frequently used corals aci oss reef zones or among