Texas Lineament Revisited William R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Big Bend and the Davis Mountains April 22-29, 2017

Texas Big Bend and the Davis Mountains Participants: Anne, Craig, David, Frank, Hilary, Jan, Joan, Judith, Lori, Linda, Neil, Skip and Stephen April 22-29, 2017 GUIDES Woody Wheeler and Lynn Tennefoss Sunset through "The Window" at Chisos Basin, Big Bend National Park Day One: El Paso to McNary Reservoir, Balmorhea State Park and Fort Davis Appropriately, we started this journey on Earth Day. We departed from El Paso on an unusually cool but sunny day – ideal for travelling. El Paso and its suburbs swiftly gave way to the vast expanses of the Chihuahuan Desert. An hour east, and well into the desert, we exited off the freeway at McNary Reservoir. At the exit underpass, we found a small colony of Cave Swallows searching for nest sites. This was a life bird for many in our group. Nearby, we pulled into the completely unassuming McNary Reservoir. From below it appears to be a scrubby, degraded bank. Upon cresting the bank, however, there is a sizeable reservoir. Here we found Clark’s Grebes performing a small portion of their spectacular mating dance that resembles a synchronized water ballet. Western Grebes were also nearby, as were a variety of wintering waterfowl and an unexpected flock of Willet. Gambel’s Quail perched conspicuously and called loudly from the shore. Just as we were about to depart, Lynn spotted a lone Ruddy Duck bringing our total to 17 species of Gambel's Quail birds at our first stop. We stopped for lunch at a colorful Mexican restaurant in Van Horn that has hosted a number of celebrities over the years. -

Grants in Action by STEVE WAGNER

NO AMOUNT OF MONEY Grants in Action BY STEVE WAGNER VOLUNTEERS FIND PERSONAL REWARDS IN A WORK PROJECT INSPIRED BY DESERT BIGHORN SHEEP, BUT WHICH BENEFITS ALL KINDS OF WILDLIFE. REPRINTED FROM GAME TRAILS SUMMER 2015 NO AMOUNT OF MONEY irty, smelly and exhausted, Charlie Barnes has never been more gratified. D The DSC Life Member from Trophy Club, Texas, lays down his tools, pulls off his work gloves, draws a deep breath of desert air and bellies up to a tailgate, where a troop of equally sweaty-but-satisfied volunteers is gathering around a cooler of liquid refreshment. Sipping through dry, grinning lips, they gaze upon their collective handiwork. Together, they’ve just finished a project that changes the landscape, both literally and figuratively, for wildlife in the arid Trans-Pecos region of west Texas. Soon, many kinds of species will be sipping here, too. A new guzzler – a device to catch, store and dispense rainwater for thirsty critters – now stands ready for the next downpour. Ready to help the habitat overcome its harshest limitation. “This place has everything it needs to be great habitat for wildlife, except for water, and we just solved that problem,” says Barnes. “Building a guzzler is doing something good for the future, and there’s no amount of money that could replace what I get out of being a part of it.” He explains, “I’m a member of 11 different conservation groups and I volunteer This Reservoir stores rainwater for the dry season. for a multitude of tasks. I help raise money, organize banquets and serve on committees and boards. -

Foundation Document Big Bend National Park Texas May 2016 Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Big Bend National Park Texas May 2016 Foundation Document Unpaved road Trail Ruins S A N 385 North 0 5 10 Kilometers T Primitive road Private land within I A Rapids G 0 5 10 Miles (four-wheel-drive, park boundary O high-clearance Please observe landowner’s vehicles only) BLACK GAP rights. M WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT AREA Persimmon Gap O U N T A Stillwell Store and RV Park Graytop I N S Visitor Center on Dog Cany Trail d o a nch R 2627 TEXAS Ra a u ng Te r l i 118 Big Bend Dagger Mountain Stairway Mountain S I National Park ROSILLOS MOUNTAINS E R R A DAGGER Camels D r Packsaddle Rosillos e FLAT S Hump E v i l L I Mountain Peak i E R a C r R c Aqua Fria A i T R B n A Mountain o A e t CORAZONES PEAKS u c lat A L ROSILLOS gger F L S Da O L O A d RANCH ld M R n G a Hen Egg U O E A d l r R i Mountain T e T O W R O CHRI N R STM I A Terlingua Ranch o S L L M O a e O d d n U LA N F a TA L r LINDA I A N T G S Grapevine o d Fossil i a Spring o Bone R R THE Exhibit e Balanced Rock s G T E L E P d PAINT GAP l H l RA O N n SOLITARIO HILLS i P N E N Y O a H EV ail C A r Slickrock H I IN r LL E T G Croton Peak S S Mountain e n Government n o i I n T y u Spring v Roys Peak e E R e le n S o p p a R i Dogie h C R E gh ra O o u G l n T Mountain o d e R R A Panther Junction O A T O S Chisos Mountains r TERLINGUA STUDY BUTTE/ e C BLACK MESA Visitor Center Basin Junction I GHOST TOWN TERLINGUA R D Castolon/ Park Headquarters T X o o E MADERAS Maverick Santa Elena Chisos Basin Road a E 118 -

Texas Describes a Great Bend Between the Town of Van Horn, Tex., on BIG BEND the West, and Langtry, Tex., on the East

Big Bend NATIONAL PARK Texas describes a great bend between the town of Van Horn, Tex., on BIG BEND the west, and Langtry, Tex., on the east. During its 107-mile journey along the boundary of the park, NATIONAL PARK the river passes mainly through sandy lowlands and between banks overgrown with dense jungles of reeds. But 3 times in CONTENTS its course it cuts through 1,500-foot-deep canyons that were Page carved by its waters over a period of hundreds of thousands of Welcome 2 years. Land of the Big Bend 2 Within the park itself is a wild kind of scenery that is more Where to Go—and When 4 like that of Mexico, across the river, than that of the rest of the Taking Pictures 10 United States. The Naturalist Program 11 The desert is gouged by deep arroyos, or gullies, that expose Geology 11 colored layers of clay and rock. On this flatland, where many varieties of cactuses and other desert plants grow, birds and Plants 12 mammals native to both countries make their homes. Animals 13 Rugged mountain ranges, near and far, give assurance that Seasons 14 the desert is not endless. In the very center of the strange Big Bend's Past and Future 15 scene soar the most spectacular mountains in this part of the Other Publications 19 country—the Chisos. Their eroded peaks look like distant forts How to Reach the Park 19 and castles as they rise some 4,000 feet above the desert floor. Where to Stay 20 To the east the magnificent, stratified Sierra del Carmen guards Services 20 that border of the park, and to the south the little-known moun Precautions 21 tains of the Fronteriza disappear into the vastness of Mexico. -

Ovis Canadensis Mexicana) in SOUTHERN NEW MEXICO

52nd Meeting of the Desert Bighorn Council Las Cruces, New Mexico April 17–20, 2013 Organized by Desert Bighorn Council New Mexico Department of Game and Fish United States Army , White Sands Missile Range 1 Cover: Puma/bighorn petroglyph, photo by Casey Anderson. 52nd Meeting of the Desert Bighorn Council is published by the Desert Bighorn Council in cooperation with the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish and the United States Army - White Sands Missile Range. © 2013. All rights reserved. 2 | Desert Bighorn Council Contents List of Organizers and Sponsors 4 Desert Bighorn Council Officers 5 Session Schedules 6–10 Presentation Abstracts 11–33 52nd Meeting | 3 52nd Meeting of the Desert Bighorn Council Organizers Sponsors 4 | Desert Bighorn Council Desert Bighorn Council Officers 2013 Meeting Co-Chairs Eric Rominger New Mexico Department of Game and Fish Patrick Morrow U S Army, White Sands Missile Range Arrangements Elise Goldstein New Mexico Department of Game and Fish Technical Staff Ray Lee Ray Lee, LLC Mara Weisenberger U S Fish and Wildlife Service Elise Goldstein New Mexico Department of Game and Fish Brian Wakeling Arizona Game and Fish Department Ben Gonzales California Department of Fish and Wildlife Clay Brewer Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Mark Jorgensen Anza-Borrego Desert State Park (retired) Secretary Esther Rubin Arizona Game and Fish Department Treasurer Kathy Longshore U S Geological Survey Transactions Editor Brian Wakeling Arizona Game and Fish Department 52nd Meeting | 5 Schedule: Wednesday, April 17, 2013 3:00–8:00 p.m. Registration 6:00–8:00 p.m. Social Schedule: Thursday, April 18, 2013 MORNING SESSION 7:00–8:0 a.m. -

Geologic Map of Big Bend National Park, Texas

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3142 Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service (Pamphlet accompanies map) 2011 Geologic Map of Big Bend National Park, Texas By Kenzie J. Turner, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado, Margaret E. Berry, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado, William R. Page, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado, Thomas M. Lehman, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas Robert G. Bohannon, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado, Robert B. Scott, U.S. Geological Survey, Corvallis, Oregon, Daniel P. Miggins, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado, James R. Budahn, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado, Roger W. Cooper, Lamar University, Beaumont, Texas, Benjamin J. Drenth, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado, Eric D. Anderson, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado and Van S. Williams U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado. Photograph: Mule Ear Peaks. Mule Ear Peaks are one of the most distinctive geologic landforms in the park, and are composed of the Chisos Formation and overlying Burro Mesa Formation. Photograph: Casa Grande. Casa Grande is one of the highest peaks (7,325 feet elevation) in the Chisos Mountains, and in Texas. The peak’s name, meaning “Big House” in Spanish, comes from its massive, steep-sided profile, which towers above the Basin. Casa Grande is an extra-caldera vent, or volcanic dome, of the Pine Canyon caldera, which erupted rocks of the South Rim Formation. Photograph: The Rio Grande near the mouth of Santa Elena Canyon. As the international boundary between the U.S. and Mexico (Mexico is on the left side of the river and the U.S. -

Small-Scale Structures in the Guadalupe Mountains Region: Implication for Laramide Stress Trends in the Permian Basin Erdlac, Richard J., Jr., 1993, Pp

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/44 Small-scale structures in the Guadalupe Mountains region: Implication for Laramide stress trends in the Permian Basin Erdlac, Richard J., Jr., 1993, pp. 167-174 in: Carlsbad Region (New Mexico and West Texas), Love, D. W.; Hawley, J. W.; Kues, B. S.; Austin, G. S.; Lucas, S. G.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 44th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 357 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1993 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. -

Distribution of Mammals in the Davis Mountains, Texas and Surrounding Areas

DISTRIBUTION OF MAMMALS IN THE DAVIS MOUNTAINS, TEXAS AND SURROUNDING AREAS by Robert S. DeBaca, B.A., M.S. A Dissertation In BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved John C. Zak Chairperson of the Committee Kevin R. Mulligan Robert D. Bradley Jorge Salazar-Bravo Carleton J. Phillips Fred Hartmeister Dean of the Graduate School August, 2008 Copyright 2008, Robert S. DeBaca The mountains are fountains of men as well as of rivers, of glaciers, of fertile soil. The great poets, philosophers, prophets, able men whose thoughts and deeds have moved the world, have come down from the mountains – mountain dwellers who have grown strong there with the forest trees in Nature’s workshops. John Muir (1938) “John of the Mountains” For Hope ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am greatly indebted to numerous people and agencies for assisting with this project. I thank the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) and the Texas Nature Conservancy for the financial and logistical support for this project. TPWD extended me trapping privileges, and Linda Hedges, Kelly Bryan, and Mark Lockwood were indispensable at facilitating the project at Davis Mountains State Park. John Karges directed me to some novel trapping sites at Davis Mountains Preserve and targeted some relevant literature. Tom Johnson championed all efforts at Balmorhea State Park and Phantom Spring. I am grateful for the efforts many students and professors who performed field work at Davis Mountains Preserve, Davis Mountains State Park, Balmorhea State Park, and Phantom Spring prior to my arrival on the project. -

Guadalupe Mountains, New Mexico and Texas

INVENTORY OF THE FLORA OF THE GUADALUPE MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO AND TEXAS [SECOND WORKING DRAFT] [MARCH, 2002] Compiled by: Richard D. Worthington, Ph.D. Floristic Inventories of the Southwest Program P. O. Box 13331 El Paso, Texas 79913 El Paso, Texas March, 2002 INVENTORY OF THE FLORA OF THE GUADALUPE MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO AND TEXAS INTRODUCTION This report is a second working draft of the inventory of the flora of the Guadalupe Mountains, Eddy and Otero Cos., New Mexico and Culberson Co., Texas. I have drawn on inventory work I have done in the Sitting Bull Falls and Last Chance Canyon area of the mountains and a survey project at Manzanita Springs carried out over the past several years as well as collections made during survey work on two projects completed in 1999 (Worthington 1999a, 1999b). I have included in this report a review of almost all of the literature that deals with the flora of the study area. The goals of this project are to provide as nearly a complete inventory as possible of the flora of the Guadalupe Mts. which includes cryptogams (lichens, mosses, liverworts), to provide a nearly complete review of the literature that references the study area flora, to document where the voucher specimens are located, and to reconstruct a history of collecting efforts made in the region. Each of these activities demands a certain amount of time. Several more years of field work are contemplated. On-line resources have yet to be evaluated. The compiler of this report welcomes any assistance especially in the form of additions and corrections. -

Texas· in This Distance It Cuts Through 1,500-Foot-Deep Canyons That Were Carved by Its Waters Over a Period of Hundreds of Thou- Sands of Years

BigBend NATIONAL PARK Texas· in this distance it cuts through 1,500-foot-deep canyons that were carved by its waters over a period of hundreds of thou- sands of years. Within the park itself is a wild kind of scenery that is more BIG BEND like that of Mexico, across the river, than that of the rest of the United States. NATIONAL PARK The desert is gouged by deep arroyos, or gullies, that expose colored layers of clay and rock. On this flatland, where many varieties of cactuses and other desert plants grow, birds and CONTENTS mammals native to both countries make their homes. Page Rugged mountain ranges, near and far, give assurance that Land of the Big Bend 2 the desert is not endless. In the very center of the strange Where to Go-and When 4 scene soar the most spectacular mountains in this part of the Map of Trails in the Chisos Mountains 6-7 country-the Chisos. Their eroded peaks look like distant Taking Pictures . 10 forts and castles as they rise some 4,000 feet above the desert The Naturalist Program 10 floor. To the east the magnificent, stratified Sierra del Carmen Geology 11 guards that border of the park, and to the south this mountain Plants . 12 range disappears into the vastness of Mexico. Animals 13 The name "Chisos" expresses the mood of the country. This Seasons. 14 name, which has been interpreted as meaning "ghost," or Big Bend's Past and Future 14 "spirit," was said to have been given the mountains by the Indians. -

Conserving Evolutionary Process in the Sky Islands of Northern Mexico

Conserving Evolutionary Process in the Sky Islands of Northern Mexico by John McCormack, Graduate Student, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Center for Tropical Research, Institute of the Environment, UCLA The mixed pine-oak woodlands of the Sierra Madre mountain chains in Mexico are a significant focus of biodiversity for North America. Harboring about a third of the world’s pine and oak species, this high- elevation region is a major center of endemism for birds, reptiles, and amphibians, including several endemic bird genera such as the thick-billed (Rhynchopsitta pachyrhncha) and maroon-fronted (R. terrisi) parrot and the Sierra Madre sparrow (Xenospiza baileyi). This area was recently selected by Conservation International as an important “hotspot” – a distinction it shares with the world’s other most “biologically rich and endangered ecoregions.” This double-edged distinction is exemplified by the imperial woodpecker (Campephilus imperialis), the world’s largest woodpecker, endemic to Madrean highlands and now likely extinct. A view of the Sierra del Carmen, a sky island in Coahuila, Mexico. Chihuahuan desert in the lowlands gives way to conifer forest at high elevations. Sky islands in Texas can be seen in the distance. As the Sierra Madres approach the United States border, their massive, interconnected cordillera give way to a series of broken mountain ranges that are isolated from one another by lowland desert. These “sky islands” rise serenely from the desert and provide a refuge for cool-adapted species and a migratory destination for birds and the humans who seek them out. Biologists have long been fascinated by sky islands for the same reason that oceanic islands have held their fancy since Darwin’s time: they provide a natural laboratory of replicated habitats for the study of evolution. -

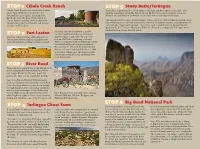

Stop 4 Stop 3 Stop 7

Sunscreen • Binoculars • Hat • Camera • Water • xtra layers xtra E • S tire • pare THINGS TO TAKE TO THINGS at the entrance stations or the visitor centers. visitor the or stations entrance the at which can be taken care of of care taken be can which an requires Park National Bend Big . entrance fee entrance protection sun , and and , , with prepared Be Park. National Bend Big in arrive you once and way, the jackets hats considerably in just a short time so be prepared for different conditions you may find both on on both find may you conditions different for prepared be so time short a just in considerably Don’t except cell service on this trip, it will be spotty at best. The weather can change change can weather The best. at spotty be will it trip, this on service cell except Don’t ownload maps or apps for the area the for apps or maps ownload D • e prepared for weather; it can change quickly in Big Bend. Big in quickly change can it weather; for prepared e B • heck fuel and fluid levels in your vehicle as well as tire pressure. tire as well as vehicle your in levels fluid and C fuel • heck BEFORE YOU GO… YOU BEFORE Canyon. Canyon. Castolon Historic District, and Tuff Tuff and District, Historic Castolon Nail and Homer Wilson Ranches, Ranches, Wilson Homer and Nail the more popular stops are the Sam Sam the are stops popular more the and geology of the area. Some of of Some area. the of geology and and learn about the plants, people, people, plants, the about learn and opportunities to stretch your legs legs your stretch to opportunities points along the drive provide provide drive the along points Roadside exhibits at various various at exhibits Roadside effort.