Lobbying for Decriminalisation, in Abel, G., Fitzgerald, L., & Healy, C., (Eds)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Milestones in NZ Sexual Health Compiled by Margaret Sparrow

MILESTONES IN NEW ZEALAND SEXUAL HEALTH by Dr Margaret Sparrow For The Australasian Sexual Health Conference Christchurch, New Zealand, June 2003 To celebrate The 25th Annual General Meeting of the New Zealand Venereological Society And The 25 years since the inaugural meeting of the Society in Wellington on 4 December 1978 And The 15th anniversary of the incorporation of the Australasian College of Sexual Health Physicians on 23 February 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pg Acknowledgments 3 Foreword 4 Glossary of abbreviations 5 Chapter 1 Chronological Synopsis of World Events 7 Chapter 2 New Zealand: Milestones from 1914 to the Present 11 Chapter 3 Dr Bill Platts MBE (1909-2001) 25 Chapter 4 The New Zealand Venereological Society 28 Chapter 5 The Australasian College 45 Chapter 6 International Links 53 Chapter 7 Health Education and Health Promotion 57 Chapter 8 AIDS: Milestones Reflected in the Media 63 Postscript 69 References 70 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr Ross Philpot has always been a role model in demonstrating through his own publications the importance of historical records. Dr Janet Say was as knowledgeable, helpful and encouraging as ever. I drew especially on her international experience to help with the chapter on our international links. Dr Heather Lyttle, now in Perth, greatly enhanced the chapter on Dr Bill Platts with her personal reminiscences. Dr Gordon Scrimgeour read the chapter on the NZVS and remembered some things I had forgotten. I am grateful to John Boyd who some years ago found a copy of “The Shadow over New Zealand” in a second hand bookstore in Wellington. Dr Craig Young kindly read the first three chapters and made useful suggestions. -

Increasing the Representativeness of Parliament in Aotearoa/New Zealand

Increasing the representativeness of Parliament in Aotearoa/New Zealand What have been the effects, and what can be learned from the process? Tina Day 20-10-05 1cjd's new zealand comment (print vers)- october 2005.dot Introduction In 1996 the Mixed Member Proportional system displaced the ‘First Past the Post’ system in Aotearoa/New Zealand (A/NZ). One result seems to have been a sustained (although fluctuating) increase in the Parliamentary representation of women, to around 30%. Other results and learning points are less clear, but potentially of great interest to us in the UK. For example: • increased representativeness increases the legitimacy, standing – and volatility – of Parliament • openness on the part of politicians results in a strong connection between public and politician • equity is seen to be about the valuing of merit but may need more positive measures to progress further towards parity. Each of these issues is discussed in more detail in this paper. Key questions for the study included: • Does the change of system guarantee more women MPs, even with a future change of government – and will the number and percentage of women continue to rise beyond the 30% level that is perhaps the minimum proportion necessary for a legislature deemed to be representative of women? • Is there any evidence in the New Zealand experience that the culture of Parliament, together with its policy making, has started to change now that there are more women in the House of Representatives as well as being more visible in other top jobs? • What about all the other, hitherto under-represented groups – how have things changed for them? This article is based on interviews with 21 MPs from all the political parties represented in the 47th (2002-2005) Parliament (including about half the total of women MPs and about one fifth of all MPs) and a handful of further interviews with other interested parties (including former Parliamentary candidates). -

House of Representatives List of Members

FORTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT OF NEW ZEALAND ___________ HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ____________ LIST OF MEMBERS 1 September 2008 MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT Member Electorate/List Party Postal Address and E-mail Address Phone and Fax Anderton, Hon Jim Freepost Parliament, (04) 470 6550 Leader, Progressive Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 495 8441 Minister of Agriculture Wellington 6160 Minister for Biosecurity Minister of Fisheries Wigram Progressive [email protected] Minister of Forestry Minister responsible for the 296 Selwyn St, Spreydon, Christchurch (03) 365 5459 Public Trust PO Box 33 164, Barrington, Christchurch Fax (03) 365 6173 Associate Minister of Health [email protected] Associate Minister for Tertiary Education Freepost Parliament (04) 471 9357 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 437 6447 Ardern MP, Shane Taranaki – King Country National Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament (04) 470 6936 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 439 6445 Auchinvole, Chris List National Wellington 6160 [email protected] (04) 470 6572 Barker, Hon Rick Freepost Parliament Fax (04) 472 8036 Minister of Internal Affairs Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Minister of Civil Defence Wellington 6160 Minister for Courts List Labour [email protected] Minister of Veterans’ Affairs Associate Minister of Justice PO Box 1245, Hastings (06) 876 8966 Fax (06) 876 4908 Freepost Parliament (04) 471 9906 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) -

Proquest Dissertations

Formation and Outcome: The Political Discourses of the New Zealand Prostitution Reform Act, 2000-2003 Catherine Zangger A Thesis in The Department of Sociology and Anthropology Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Sociology) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada July 2009 © Catherine Zangger, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63031-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63031-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extra its substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

What Is Penal Populism?

The Power of Penal Populism: Public Influences on Penal and Sentencing Policy from 1999 to 2008 By Tess Bartlett A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Criminology View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington School of Social and Cultural Studies Victoria University of Wellington June 2009 Abstract This thesis explains the rise and power of penal populism in contemporary New Zealand society. It argues that the rise of penal populism can be attributed to social, economic and political changes that have taken place in New Zealand since the postwar years. These changes undermined the prevailing penalwelfare logic that had dominated policymaking in this area since 1945. It examines the way in which ‘the public’ became more involved in the administration of penal policy from 1999 to 2008. The credibility given to a law and order referendum in 1999, which drew attention to crime victims and ‘tough on crime’ discourse, exemplified their new role. In its aftermath, greater influence was given to the public and groups speaking on its behalf. The referendum also influenced political discourse in New Zealand, with politicians increasingly using ‘tough on crime’ policies in election campaigns as it was believed that this was what ‘the public’ wanted when it came to criminal justice issues. As part of these developments, the thesis examines the rise of the Sensible Sentencing Trust, a unique law and order pressure group that advocates for victims’ rights and the harsh treatment of offenders. -

Shapeshifting: Prostitution and the Problem of Harm

SHAPESHIFTING: PROSTITUTION AND THE PROBLEM OF HARM A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF MEDIA REPORTAGE OF PROSTITUTION LAW REFORM IN NEW ZEALAND IN 2003 A thesis submitted to AUT University New Zealand in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master in Health Science JANE BARRINGTON SEPTEMBER 2008 i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................. i TABLE OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................... iv ATTESTATION OF AUTHORSHIP ............................................................................. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................ vi ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER 1: Introduction .............................................................................................. 8 Problematising Prostitution Law Reform in New Zealand ........................................... 10 Problematising Prostitution ........................................................................................... 11 Reasons for the Research .............................................................................................. 14 The First Aim of the Research .................................................................................. 17 The Second Aim of the Research ............................................................................. -

Annual Hui & Skillshare 2021

Annual Hui & Skillshare 2021 – Towards a Bold Future The Piano: Centre for Music and the Arts, 156 Armagh Street, Christchurch Central City, Christchurch 8011 Sessions with an * will be livestreamed Friday 30 May 2021 18:30 - Pub social drinks at Dux Central, 144 Lichfield Street, Central Christchurch ANNUAL HUI Saturday 29 May 2021, 9am – 4pm 8.30am Registration opens 9:00am Mihi Whakatau Jonathon Hagger 9.05am Opening words & candle lighting Heather Hayden 9:15am Introductions Meg de Ronde 9:30am Campaign speed dating – The Year that Was Campaigns Team 10.30am Morning tea 11.00* 60 Years of Human Rights - panel session (livestreamed) Tim Barnett, Carwyn Jones, and Meg de Ronde 12.00pm Lunch 1.00pm* Amnesty International NZ AGM (Official Business) (livestreamed) Chairperson Including: - Election of meeting officers and approval of standing orders - Board Team member elections and resolutions - Election of two Board members including Vice Chair and Treasurer - Annual Report & finances discussion, with resolution voting - Incorporated Societies Act presentation Heather Hayden 2.00pm* Guest speaker: Behrouz Boochani (livestreamed) Behrouz Boochani 3.00pm Afternoon tea – Happy Birthday to Amnesty cake and drinks 3.30pm Dove Awards and inaugural winners of the Gary Ware Legacy Award Margaret Taylor 4pm Wrap up and End Meg de Ronde 6:00pm Social Dinner - Saigon Centre, South City Shopping Centre, Christchurch, 8011 SKILLSHARE Sunday, 30 May, 9.00am – 3.30pm 9.00am Welcome & Karakia 9.10am Discussion on improving youth participation at governance level Alva Feldmeier 10.00am Morning tea 10.30am Talking about the rights of people in detention Campaigning to end Tania Sawicki-Mead, detention of asylum seekers in NZ Justspeak. -

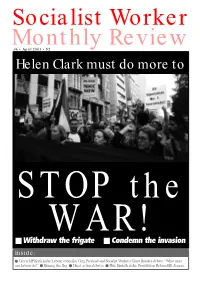

Helen Clark Must Do More To

Socialist Worker Monthly Review #6 • April 2003 • $2 Helen Clark must do more to STOP the WAR! ■ Withdraw the frigate ■ Condemn the invasion Inside: ● Green MP Keith Locke, Labour councillor Greg Presland and Socialist Worker’s Grant Brookes debate “What more can Labour do?” ● Burning the flag ● Direct action debates ● Plus: Kinleith strike, Prostitution Reform Bill, & more. Socialist Worker Monthly Review April 2003 1 What’s on APRIL 12 WHO SAYS? International Day of “Resistance has Action Against the War been minimal Details available as Socialist ■ WELLINGTON protest action. Details to be becausec few Iraqis Worker Monthly Review Peace Action Wellington have confirmed. Contact Brian, will fight for goes to press: called a protest for either 472 7473 or Fiona Saddam – and even April 11 (Friday night) or April [email protected]. ■ AUCKLAND 12. Further details to be fewer will die for Gather at 12 noon, Western confirmed. Contact Grant, 566 ■ OTHER CENTRES him.” Park (corner Ponsonby Rd & K 8538 or e-mail Information on actions in Richard Perle, key Rd). [email protected] other centres will be posted Pentagon advisor to Organised by Global Peace & by Peace Movement Aotearoa Justice Auckland. ■ DUNEDIN as it becomes available, George Bush. For more information, phone Dunedin Coalition Against www.converge.org.nz/pma/ 361 6989. the War will be organising date.htm “Our forces will be met with applause and sweets and flowers.” Pentagon official. “I’m not fighting for Saddam Hussein, I’m fighting for Iraq.” Nasr Al Hussein, one of hundreds of Iraqi exiles queuing to board coaches in WASHINGTON LONDON AUCKLAND Jordan to return to Baghdad. -

Prostitution Reform Bill

Prostitution Reform Bill Member's Bill As reported from the Justice and Electoral Committee Commentary Recommendation The Justice and Electoral Committee has examined the Prostitution Reform Bill (the bill) and recommends by majority that it be passed with the amendments shown. Introduction Prostitution itself is not an illegal activity in New Zealand. However, a range of offences can be committed in association with acts of prostitution and the law is such that for most forms of prostitution, it is likely a law will be broken at some stage. The purpose of the bill is to decriminalise such activities and make prostitution subject to special provisions in addition to the laws and controls that regulate other businesses. This purpose is not intended to equate with the promotion of prostitution as an acceptable career option but instead to enable sex workers to have and access the same protections afforded to other workers. The bill, as introduced, has the stated aims of: • Safeguarding the human rights of sex workers. • Protecting sex workers from exploitation. • Promoting the welfare and occupational safety and health of sex workers. • Creating an environment that is conducive to public health. 66Ð2 2 Prostitution Reform Commentary • Protecting children from exploitation in relation to prostitution. Through these measures, supporters of the bill intend it to facilitate contact with occupational safety and health agencies, support the development of models of collective and self-managed prostitution businesses, and make exit from the industry easier. The bill, as introduced, requires operators of brothels to promote safer sex practices by displaying and providing information about safer sex practices. -

Word Style Book

Word Style Book ABOUT THIS MANUAL The Word Style Book has been prepared in the Hansard Office to function in conjunction with the 10th edition of the Concise Oxford Dictionary as the dictionary for that office, to be consulted in the preparation of the parliamentary debates for publication. It is a guide to how to treat words in the text of Hansard, and not a guide to precedents or setting up members’ names. The use of hyphens is being kept to a minimum, in line with COD practice as stated in the preface to the 10th edition. For guidance on how a word or expression is treated in Hansard, consult the Word Style Book before the COD. The treatment of words not covered in either reference text will need to be confirmed for inclusion in the Word Style Book updates, which are published regularly. USER GUIDE to the HANSARD WORD STYLE BOOK I ENTRIES IN WORD STYLE BOOK (WSB) accounts alphanumeric classifications animals chemicals and organic compounds cities, countries, geographical features, etc., if not in atlas or Wises compound words diseases drugs (generic) foreign words and phrases games indices Māori words (listed separately) measurements misused or misspelt words mottos and proverbs new words “non-words” that may be used (eg., bikkie) parliamentary terms and organisations, positions, etc. associated with Parliament plants qualifications religions statutory holidays taxes technical terms words that reflect a specifically NZ usage or spelling that differs from that in the COD II ENTRIES IN REFERENCE LIST airports, ports computer programs -

— Protest on February 15 —

Socialist Worker Monthly#4 • February 2003 • $2 Review WE CAN STOP THIS WAR — PROTEST ON FEBRUARYSocialist Worker Monthly Review15 February — 2003 1 What’s on LONDON NEW YORK ROME ATHENS BRISBANE February 15 – International day of action against the war on Iraq Up to 10 million people around the world [email protected] Maunder tel 732 4010 e-mail are expected to protest against war on Iraq [email protected] or Rev Alan PALMERSTON NORTH Cummins tel (03) 768 7667. on February 15. (Note change of date – 13 February) Some of the cities organising protests are Peace March in solidarity with the inter- CHRISTCHURCH shown above. national protest against the greatly esca- Celebrate the International Day of Anti- It will be by far the biggest and most lating the 12 year war on Iraq. Assemble War Action at the Peace Picnic – with en- widespread demonstration of opposition yet at 11-45am on the Railway land, Pitt St for tertainment including The Cooltones, a march to the Square and Te Marae o Oakley Grenell, Anne Low, DJs, stalls and seen. Join the actions in your area! Hine. All welcome to contribute / speak. speakers. Please bring a white flower with For more info contact Manawatu Peace you. From 1pm, at Victoria Square, for AUCKLAND Collective, tel (06) 357 7882, email more info contact Peace Action Network March up Queen Street from QEII Square [email protected] tel (03) 981 2825. at 12 noon. Organised by Global Peace & Justice Auckland. For more info contact WELLINGTON DUNEDIN John Minto, email [email protected], or March and Rally for Peace in the Middle March and Rally to Oppose War in Iraq, Mike Treen email [email protected]. -

IMPORTANT NOTICE IMPORTANT NOTICE Labour Is Trying to Decimate the NZ Health Products Industry Labour Is Trying to Decimate the NZ Health Products Industry

IMPORTANT NOTICE IMPORTANT NOTICE Labour is trying to decimate the NZ Health Products Industry Labour is trying to decimate the NZ Health Products Industry The Labour Government is trying to change the way in which all Natural Health Products (NHPs) The Labour Government is trying to change the way in which all Natural Health Products (NHPs) & medical devices are regulated. They plan to treat them as medicines and give the power to & medical devices are regulated. They plan to treat them as medicines and give the power to control them to the controversial Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) control them to the controversial Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) We know from the Australian experience that this would mean; We know from the Australian experience that this would mean; • Fewer products available - consumer choice reduced • Fewer products available - consumer choice reduced • Unnecessary bureaucracy and cost • Unnecessary bureaucracy and cost • Increased cost to consumers • Increased cost to consumers • Natural health products & medical devices all controlled like drugs • Natural health products & medical devices all controlled like drugs • Many NZ businesses forced to close - jobs lost • Many NZ businesses forced to close - jobs lost • There will be little NZ can do to protect itself – Australia would make decisions for NZ • There will be little NZ can do to protect itself – Australia would make decisions for NZ The Australian TGA (which would take over NZ’s health products industry) is known to use an The Australian TGA (which would take over NZ’s health products industry) is known to use an extremely heavy-handed approach.