Traditional Authorities' Peacemaking Role in Darfur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darfur Genocide

Darfur genocide Berkeley Model United Nations Welcome Letter Hi everyone! Welcome to the Darfur Historical Crisis committee. My name is Laura Nguyen and I will be your head chair for BMUN 69. This committee will take place from roughly 2006 to 2010. Although we will all be in the same physical chamber, you can imagine that committee is an amalgamation of peace conferences, UN meetings, private Janjaweed or SLM meetings, etc. with the goal of preventing the Darfur Genocide and ending the War in Darfur. To be honest, I was initially wary of choosing the genocide in Darfur as this committee’s topic; people in Darfur. I also understood that in order for this to be educationally stimulating for you all, some characters who committed atrocious war crimes had to be included in debate. That being said, I chose to move on with this topic because I trust you are all responsible and intelligent, and that you will treat Darfur with respect. The War in Darfur and the ensuing genocide are grim reminders of the violence that is easily born from intolerance. Equally regrettable are the in Africa and the Middle East are woefully inadequate for what Darfur truly needs. I hope that understanding those failures and engaging with the ways we could’ve avoided them helps you all grow and become better leaders and thinkers. My best advice for you is to get familiar with the historical processes by which ethnic brave, be creative, and have fun! A little bit about me (she/her) — I’m currently a third-year at Cal majoring in Sociology and minoring in Data Science. -

Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 Highlights

Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 UNICEF and partners assess damage to communities in southern Khartoum. Sudan was significantly affected by heavy flooding this summer, destroying many homes and displacing families. @RESPECTMEDIA PlPl Reporting Period: July-September 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers • Flash floods in several states and heavy rains in upriver countries caused the White and Blue Nile rivers to overflow, damaging households and in- 5.39 million frastructure. Almost 850,000 people have been directly affected and children in need of could be multiplied ten-fold as water and mosquito borne diseases devel- humanitarian assistance op as flood waters recede. 9.3 million • All educational institutions have remained closed since March due to people in need COVID-19 and term realignments and are now due to open again on the 22 November. 1 million • Peace talks between the Government of Sudan and the Sudan Revolu- internally displaced children tionary Front concluded following an agreement in Juba signed on 3 Oc- tober. This has consolidated humanitarian access to the majority of the 1.8 million Jebel Mara region at the heart of Darfur. internally displaced people 379,355 South Sudanese child refugees 729,530 South Sudanese refugees (Sudan HNO 2020) UNICEF Appeal 2020 US $147.1 million Funding Status (in US$) Funds Fundi received, ng $60M gap, $70M Carry- forward, $17M *This table shows % progress towards key targets as well as % funding available for each sector. Funding available includes funds received in the current year and carry-over from the previous year. 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF’s 2020 Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) appeal for Sudan requires US$147.11 million to address the new and protracted needs of the afflicted population. -

Nomads' Settlement in Sudan: Experiences, Lessons and Future Action

Nomads’ Settlement in Sudan: Experiences, Lessons and Future action (STUDY 1) Copyright © 2006 By the United Nations Development Programme in Sudan House 7, Block 5, Avenue P.O. Box: 913 Khartoum, Sudan. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retreival system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. Printed by SCPP Editor: Ms: Angela Stephen Available through: United Nations Development Programme in Sudan House 7, Block 5, Avenue P.O. Box: 913 Khartoum, Sudan. www.sd.undp.org The analysis and policy recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations, including UNDP, its Executive Board or Member States. This study is the work of an independent team of authors sponsored by the Reduction of Resource Based Conflcit Project, which is supported by the United Nations Development Programme and partners. Contributing Authors The Core Team of researchers for this report comprised of: 1. Professor Mohamed Osman El Sammani, Former Professor of Geography, University of Khartoum, Team leader, Principal Investigator, and acted as the Report Task Coordinator. 2. Dr. Ali Abdel Aziz Salih, Ph.D. in Agricultural Economics, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Khartoum. Preface Competition over natural resources, especially land, has become an issue of major concern and cause of conflict among the pastoral and farming populations of the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. Sudan, where pastoralists still constitute more than 20 percent of the population, is no exception. Raids and skirmishes among pastoral communities in rural Sudan have escalated over the recent years. -

North Darfur II

Darfur Humanitarian Profile Annexes: I. North Darfur II. South Darfur III. West Darfur Darfur Humanitarian Profile Annex I: North Darfur North Darfur Main Humanitarian Agencies Table 1.1: UN Agencies Table 1.2: International NGOs Table 1.3: National NGOs Intl. Natl. Vehicl Intl. Natl. Vehic Intl. Natl. Vehic Agency Sector staff staff* es** Agency Sector staff staff* les** Agency Sector staff staff les FAO 10 1 2 2 ACF 9 4 12 3 Al-Massar 0 1 0 Operations, Logistics, Camp IOM*** Management x x x GAA 1, 10 1 3 2 KSCS x x x OCHA 14 1 2 3 GOAL 2, 5, 8, 9 6 117 10 SECS x x x 2, 3, 7, UNDP*** 15 x x x ICRC 12, 13 6 20 4 SRC 1, 2 0 10 3 2, 4, 5, 6, UNFPA*** 5, 7 x x x IRC 9, 10, 11 1 5 4 SUDO 5, 7 0 2 0 Protection, Technical expertise for UNHCR*** site planning x x x MSF - B 5 5 10 0 Wadi Hawa 1 1 x 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, Oxfam - UNICEF 9 11, 12 4 5 4 GB 2, 3, 4 5 30 10 Total 1 14 3 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, UNJLC*** 17 x x x SC-UK 11, 12 5 27 8 Technical Spanish UNMAS*** advice x x x Red Cross 3, 4 1 0 1 UNSECOORD 16 1 1 1 DED*** x x x WFP 1, 9, 11 1 12 5 NRC*** x x x WHO 4, 5, 6 2 7 2 Total 34 224 42 Total 10 29 17 x = information unavailable at this time Sectors: 1) Food 2) Shelter/NFIs 3) Clean water 4) Sanitation 5) Primary Health Facilities *Programme and project staff only. -

Soil and Oil

COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE COALITION FOR I NTERNATIONAL JUSTICE SOIL AND OIL: DIRTY BUSINESS IN SUDAN February 2006 Coalition for International Justice 529 14th Street, N.W. Suite 1187 Washington, D.C., 20045 www.cij.org February 2006 i COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE COALITION FOR I NTERNATIONAL JUSTICE SOIL AND OIL: DIRTY BUSINESS IN SUDAN February 2006 Coalition for International Justice 529 14th Street, N.W. Suite 1187 Washington, D.C., 20045 www.cij.org February 2006 ii COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE © 2006 by the Coalition for International Justice. All rights reserved. February 2006 iii COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CIJ wishes to thank the individuals, Sudanese and not, who graciously contributed assistance and wisdom to the authors of this research. In particular, the authors would like to express special thanks to Evan Raymer and David Baines. February 2006 iv 25E 30E 35E SAUDI ARABIA ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT LIBYA Red Lake To To Nasser Hurghada Aswan Sea Wadi Halfa N u b i a n S aS D e s e r t ha ah raar a D De se es re tr t 20N N O R T H E R N R E D S E A 20N Kerma Port Sudan Dongola Nile Tokar Merowe Haiya El‘Atrun CHAD Atbara KaroraKarora RIVER ar Ed Damer ow i H NILE A d tb a a W Nile ra KHARTOUM KASSALA ERITREA NORTHERN Omdurman Kassala To Dese 15N KHARTOUM DARFUR NORTHERN 15N W W W GEZIRA h h KORDOFAN h i Wad Medani t e N i To le Gedaref Abéche Geneina GEDAREF Al Fasher Sinnar El Obeid Kosti Blu WESTERN Rabak e N i En Nahud le WHITE DARFUR SINNAR WESTERN NILE To Nyala Dese KORDOFAN SOUTHERN Ed Damazin Ed Da‘ein Al Fula KORDOFAN BLUE SOUTHERN Muglad Kadugli DARFUR NILE B a Paloich h 10N r e 10N l 'Arab UPPER NILE Abyei UNIT Y Malakal NORTHERN ETHIOPIA To B.A.G. -

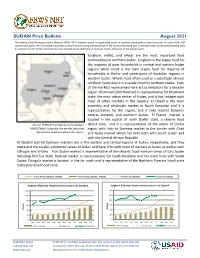

SUDAN Price Bulletin August 2021

SUDAN Price Bulletin August 2021 The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) monitors trends in staple food prices in countries vulnerable to food insecurity. For each FEWS NET country and region, the Price Bulletin provides a set of charts showing monthly prices in the current marketing year in selected urban centers and allowing users to compare current trends with both five-year average prices, indicative of seasonal trends, and prices in the previous year. Sorghum, millet, and wheat are the most important food commodities in northern Sudan. Sorghum is the staple food for the majority of poor households in central and eastern Sudan regions while millet is the main staple food for majority of households in Darfur and some parts of Kordofan regions in western Sudan. Wheat most often used as a substitute all over northern Sudan but it is a staple food for northern states. Each of the markets represented here act as indicators for a broader region. Khartoum (Om Durman) is representative for Khartoum state, the main urban center of Sudan, and it has linkages with most of other markets in the country. El Obeid is the main assembly and wholesale market in North Kordofan and it is representative for the region, and it links market between central, western, and southern Sudan. El Fasher market is located in the capital of north Darfur state, a chronic food Source: FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges deficit area, and it is representative of the entire of Darfur FAMIS/FMoA, Sudan for the market data and region with links to Geneina market in the border with Chad information used to produce this report. -

The Maban Languages and Their Place Within Nilo-Saharan

The Maban languages and their place within Nilo-Saharan DRAFT CIRCUALTED FOR DISCUSSION NOT TO BE QUOTED WITHOUT PERMISSION Roger Blench McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Department of History, University of Jos Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This version: Cambridge, 10 January, 2021 The Maban languages Roger Blench Draft for comment TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS.........................................................................................................................................i ACRONYMS AND CONVENTIONS...................................................................................................................ii 1. Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................3 2. The Maban languages .........................................................................................................................................3 2.1 Documented languages................................................................................................................................3 2.2 Locations .....................................................................................................................................................5 2.3 Existing literature -

How to Implement Sudan's New Peace Agreement

The Rebels Come to Khartoum: How to Implement Sudan’s New Peace Agreement Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°168 Khartoum/Nairobi/Brussels, 23 February 2021 What’s new? A peace agreement signed on 3 October 2020 paves the way for armed and unarmed opposition groups in Sudan to join the transitional government, dra- matically expanding representation of the country’s peripheries during the interim period before elections. The two most powerful rebel movements remain outside the accord, however. Why does it matter? Clinching the agreement was necessary for the country’s transition but implementation poses challenges. The agreement risks bloating the military and sets up a prospective political alliance between the rebels and Sudanese security forces, which could further sideline the government’s civilian cabinet and threaten to bury its reform agenda. What should be done? The interim government should negotiate with holdout rebels to bring them into the transition. Sudan’s international partners should press for security sector reform that decreases the size and political dominance of a newly expanded military while funding and supporting the authorities’ spending commit- ments in the peripheries. I. Overview Sudan’s October 2020 peace agreement, involving the interim government and rebel movements in Darfur and the Two Areas, among others, is an important step in the country’s transition after the ouster of former President Omar al-Bashir. The deal allows for representatives from armed groups in the country’s peripheries to take government posts and for significant public money to go to these areas. It is a way to rebalance the Nile Valley elites’ decades-long domination of Sudan’s political system. -

Cameroun) Dessin De Christian SEIGNOBOS

BULLETIN MEGA-TCHAD 2000 / 1 & 2 Méga-Tchad 2000 / 1 & 2 MÉGA-TCHAD n° 2000 / 1 & 2 Année 2000 ____________________________ Coordination : Catherine BAROIN (CNRS) Jean BOUTRAIS (IRD - ex Orstom) Dymitr IBRISZIMOW (Universität Bayreuth) Henry TOURNEUX (CNRS) CNRS, Laboratoire de Recherches Universität Bayreuth sur l’Afrique Maison René Ginouvès Afrikanistik II 21, allée de l’Université 92023 NANTERRE Cédex D-95440 Bayreuth FRANCE DEUTSCHLAND CNRS / LLACAN Langage, Langues et Cultures d’Afrique Noire 7, rue Guy-Moquet 94801 VILLEJUIF Cédex FRANCE Adresser toute correspondance à : MÉGA-TCHAD Boîte n° 7 Maison René Ginouvès Téléphone : 01 46 69 26 27 21, allée de l’Université Fax : 01 46 69 26 28 92023 NANTERRE Cédex E-mail : [email protected] FRANCE Les auteurs sont seuls responsables du contenu de leurs articles et comptes rendus 3 Méga-Tchad 2000 / 1 & 2 ISSN 0997-4547 Couverture : Case munjuk de la région de Guirvidig (Cameroun) Dessin de Christian SEIGNOBOS 4 Méga-Tchad 2000 / 1 & 2 SSOOMMMMAAIIRREE • Editorial : « Un outil de travail collectif » ....................................p. 7 par Catherine BAROIN • In memoriam Bernard LANNE, Patrick PARIS.....................................p. 8 • Réseau Méga-Tchad : le prochain colloque..................................p. 9 • Annonces ...................................................................................p. 10 - Colloques : langues tchadiques, linguistique nilo-saharienne - Les décors de céramiques imprimées du Sahara - Séances de séminaires intéressant la zone Méga-Tchad -

General Presentation of Results

HUMANITARIAN AID ORGANISATION Return-oriented Profiling in the Southern Part of West Darfur and corresponding Chadian border area General presentation of results July 2005 INDEX INTRODUCTION pag. 3 PART 1: ANALYSIS OF MAIN TRENDS AND ISSUES IDENTIFIED pag. 6 Chapter 1: Demographic Background pag. 6 1.1 Introduction pag. 6 1.2 The tribes pag. 8 1.3 Relationship between African and Arabs tribes pag. 11 Chapter 2: Displacement and Return pag. 13 2.1 Dispacement pag. 13 2.2 Return pag. 16 2.3 The creation of “model” villages pag. 17 Chapter 3: The Land pag. 18 3.1 Before the crisis pag. 18 3.2 After the crisis pag. 19 Chapter 4: Security pag. 22 4.1 Freedom of movement pag. 22 4.2 Land and demography pag. 23 PART 2: ANALYSIS OF THE SECTORAL ISSUES pag. 24 Chapter 1: Sectoral Gaps and Needs pag. 24 1.1 Health pag. 24 1.2 Education pag. 27 1.3 Water pag. 32 1.4 Shelter pag. 36 1.5 Vulnerable pag. 37 1.6 International Presence pag. 38 PART 3: SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS pag. 42 Annex 1: Maps pag. 45 i Bindisi/Chadian Border pag. 45 ii Um-Dukhun/Chadian Border pag. 46 iii Mukjar pag. 47 iiii Southern West Darfur – Overview pag. 48 Annex 2: Geographical Summary of the Villages Profiled pag. 49 i Bindisi Administrative Unit pag. 49 ii Mukjar Administrative Unit pag. 61 iii Um-Dukhun Administrative Unit pag. 71 iiii Chadian Border pag. 91 iiiii Other Marginal Areas (Um-Kher, Kubum, Shataya) pag. 102 INTRODUCTION The current crisis has deep roots in the social fabric of West Darfur. -

SUDAN: West Darfur State UNHCR Presence and Refugee & IDP Locations

A A A SUDAN: West Darfur State UNHCR presence and refugee & IDP locations As of 18 Sep 2019 Ardamata #B A #BEl Riad Tandubayah BAbu Zar Sigiba El Geneina#C# #BAl Hujaj Girgira #BJammaa #BKrinding 1 & 2 Mastura\Sania WEST DARFUR #BKrinding 2 Dankud #B Kaidaba KULBUS Falankei Wadi Bardi village #B Kul#bus Abu Rumayl #B Bardani NORTH DARFUR Selea #B Istereina Aro Shorou Taziriba Hijeilija#B Gosmino #B Manjura A #B JEBEL MOON Ginfili Ngerma Djedid Abu Surug SIRBA #B Sirba Melmelli Armankul Abu Shajeira #B B # Bir Dagig Hamroh #B Kondobe #B Kuka WEST DARFUR A Kurgo CHAD Sultan house Birkat Tayr Kawm Dorti #B Abd Allah El RiadAro daBmata Abu #Zar A Jammaa B #B #Krinding 1 & 2 Al Hujaj #BC# #BBB Kaira Krinding 2## Derjeil El Geneina Kreinik EL GENEINA #B KREINIK A Geneina Goker #B DogoumSisi Nurei #B Misterei A #B A Kajilkajili Hagar Jembuh Murnei Kango Haraza Awita #B o #B A Ulang ZalingeiC# EGYPT SAUDI BEIDA Chero Kasi ARABIA LIBYA Zalingei Tabbi Nyebbei HABILA R Kortei e d S Red Sea e Arara a Beida town Northern Beida #B #B Arara AlwadiHabila Madares Nur Al Huda village River Nile #BBC# CHAD Al Salam# North A UNHCR office Darfur Khartoum Kassala Habila North ERITREA Kordofan Refugee Sites Futajiggi West El Gazira Darfur White Gedaref Sala + Lor CENTRAL DARFUR Nile POC IDP camp/sites Central West Sennar #B Darfur Kordofan Blue #B South Nile C# Refugee settlement South East Kordofan Darfur Darfur ETHIOPIA D Crossing point SOUTH SUDAN Main town Secondary town Seilo o Airfields FORO BARANGA SOUTH DARFUR Boundaries & Roads Mogara International boundary Foro Burunga State boundary #BC# Goldober Locality boundary Foro Baranga Primay road A Secondary road 5km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Darfur and the Battle for Khartoum

Institute for Security Studies Situation Report Date Issued: 04 September 2006 Author: Mariam Bibi Jooma1 Distribution: General Contact: [email protected] Darfur and the Battle for Khartoum Sudan’s western region of Darfur has frequently featured in the headlines since Introduction the outbreak of major violence there in 2003. Indeed, it often seemed that international interest would remain focused upon Darfur, given the scale of human suffering and the immensity of the challenges facing the African Union’s (AU) peacekeeping operations in that vast area. It was little surprise, then, that the signing of the Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA) on 5 May this year between the Government of Sudan and the Minni Arkoi Minnawi faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) was greeted with such relief in the media. Developments since the signing of the DPA, however, suggest that the political commitment to implementing its terms remains extremely weak, and there is a continued polarisation of affected ethnic communities, particularly within displacement camps, sometimes with fatal consequences. This has happened despite the appointment on 7 August of Minni Arkoi Minnawi, as the Special Assistant to the Sudanese President. Moreover, the period between May and July 2006 has seen the highest number of fatalities among aid workers since the beginning of 2003.2 This is quite aside from the continuing killing of Darfurians on a daily basis. In this unpredictable environment, the local population has become increasingly cynical of the potential peacekeeping role of the African Union Mission (AMIS) deployed to observe the implementation of the 2004 ceasefire agreement. A growing number of fatalities suffered by AMIS troops themselves in Darfur suggests that the African Union’s role as mediator and guarantor for the implementation of the DPA is being overtly challenged.