DEF.Irish Film and TV Section TRACY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rte Guide Tv Listings Ten

Rte guide tv listings ten Continue For the radio station RTS, watch Radio RTS 1. RTE1 redirects here. For sister service channel, see Irish television station This article needs additional quotes to check. Please help improve this article by adding quotes to reliable sources. Non-sources of materials can be challenged and removed. Найти источники: РТЗ Один - новости газеты книги ученый JSTOR (March 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) RTÉ One / RTÉ a hAonCountryIrelandBroadcast areaIreland & Northern IrelandWorldwide (online)SloganFuel Your Imagination Stay at home (during the Covid 19 pandemic)HeadquartersDonnybrook, DublinProgrammingLanguage(s)EnglishIrishIrish Sign LanguagePicture format1080i 16:9 (HDTV) (2013–) 576i 16:9 (SDTV) (2005–) 576i 4:3 (SDTV) (1961–2005)Timeshift serviceRTÉ One +1OwnershipOwnerRaidió Teilifís ÉireannKey peopleGeorge Dixon(Channel Controller)Sister channelsRTÉ2RTÉ News NowRTÉjrTRTÉHistoryLaunched31 December 1961Former namesTelefís Éireann (1961–1966) RTÉ (1966–1978) RTÉ 1 (1978–1995)LinksWebsitewww.rte.ie/tv/rteone.htmlAvailabilityTerrestrialSaorviewChannel 1 (HD)Channel 11 (+1)Freeview (Northern Ireland only)Channel 52CableVirgin Media IrelandChannel 101Channel 107 (+1)Channel 135 (HD)Virgin Media UK (Northern Ireland only)Channel 875SatelliteSaorsatChannel 1 (HD)Channel 11 (+1)Sky IrelandChannel 101 (SD/HD)Channel 201 (+1)Channel 801 (SD)Sky UK (Northern Ireland only)Channel 161IPTVEir TVChannel 101Channel 107 (+1)Channel 115 (HD)Streaming mediaVirgin TV AnywhereWatch liveAer TVWatch live (Ireland only)RTÉ PlayerWatch live (Ireland Only / Worldwide - depending on rights) RT'One (Irish : RTH hAon) is the main television channel of the Irish state broadcaster, Raidi'teilif's Siranne (RTW), and it is the most popular and most popular television channel in Ireland. It was launched as Telefes Siranne on December 31, 1961, it was renamed RTH in 1966, and it was renamed RTS 1 after the launch of RTW 2 in 1978. -

Ho Li Day Se Asons and Va Ca Tions Fei Er Tag Und Be Triebs Fe Rien BEAR FAMILY Will Be on Christmas Ho Li Days from Vom 23

Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 12. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 12th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 12. Janu ar 2004 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken day 12th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - wir uns für die gute Zusam menar beit im ver gange nen mers for their co-opera ti on in 2003. It has been a Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY...............................2 BEAT, 60s/70s.........................66 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. ........................19 SURF ........................................73 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER ..................22 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY .......................75 WESTERN .....................................27 BRITISH R&R ...................................80 C&W SOUNDTRACKS............................28 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT ........................80 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS ......................28 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND ...............29 POP ......................................82 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE .................30 POP INSTRUMENTAL ............................90 -

You Can Find Details of All the Films Currently Selling/Coming to Market in the Screen

1 Introduction We are proud to present the Fís Éireann/Screen Irish screen production activity has more than Ireland-supported 2020 slate of productions. From doubled in the last decade. A great deal has also been comedy to drama to powerful documentaries, we achieved in terms of fostering more diversity within are delighted to support a wide, diverse and highly the industry, but there remains a lot more to do. anticipated slate of stories which we hope will Investment in creative talent remains our priority and captivate audiences in the year ahead. Following focus in everything we do across film, television and an extraordinary period for Irish talent which has animation. We are working closely with government seen Irish stories reach global audiences, gain and other industry partners to further develop our international critical acclaim and awards success, studio infrastructure. We are identifying new partners we will continue to build on these achievements in that will help to build audiences for Irish screen the coming decade. content, in more countries and on more screens. With the broadened remit that Fís Éireann/Screen Through Screen Skills Ireland, our skills development Ireland now represents both on the big and small division, we are playing a strategic leadership role in screen, our slate showcases the breadth and the development of a diverse range of skills for the depth of quality work being brought to life by Irish screen industries in Ireland to meet the anticipated creative talent. From animation, TV drama and demand from the sector. documentaries to short and full-length feature films, there is a wide range of stories to appeal to The power of Irish stories on screen, both at home and all audiences. -

Page 1 of 125 © 2016 Factiva, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Colin's Monster

Colin's monster munch ............................................................................................................................................. 4 What to watch tonight;Television.............................................................................................................................. 5 What to watch tonight;Television.............................................................................................................................. 6 Kerry's wedding tackle.............................................................................................................................................. 7 Happy Birthday......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Joke of the year;Sun says;Leading Article ............................................................................................................... 9 Atomic quittin' ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Kerry shows how Katty she really is;Dear Sun;Letter ............................................................................................ 11 Host of stars turn down invites to tacky do............................................................................................................. 12 Satellite & digital;TV week;Television.................................................................................................................... -

Airs Ii Barndances Ii Hornpipes Ii Jigs Ii Marches Iv Pipe Marches

Airs ii Barndances ii Hornpipes ii Jigs ii Marches iv Pipe Marches, Pibrochs v Polkas v Quicksteps vi Reels vi Schottisches viii Shetland_Reels viii Slip_Jigs viii Slow_Airs viii Strathspeys viii Two-Steps ix Waltzes ix Miscellaneous x i Airs 1. 59. The Greencastle Hornpipe #1 41. 1. The Haunting 2. 60. The Galway Hornpipe 42. 2. Macfarlane O'The Sprots O'Burnieboozie 3. 61. The Kildare Hornpipe #1 43. 3. A Guid New Year 4. 62. Phil The Fluter's Ball 44. 4. This Is No My Ain Lassie #1 4. 63. The Humours of California 44. 5. Sally Gardens #1 5. 64. The Boys of Bluehill 45. 6. This Is No My Ain Lassie #2 5. 65. The Echo 45. 7. Sally Gardens #2 6. 66. The Gypsies Hornpipe #2 46. 8. The Sally Gardens #3 6. 67. The Greencastle Hornpipe 46. 9. Fear a Phige 7. 68. The Liverpool Hornpipe 47. 10. Pentland Hills 7. 69. Dunphy's Hornpipe 47. 11. John Roy Lyall 8. 70. The Kildare Hornpipe #2 48. 12. The Dark Woman of The Glen 9. 71. The Stack of Barley 48. 13. The Dying Year 10. 72. Julia's Wedding 49. 14. Griogal Chridhe 10. 73. Jock Tamson's Hornpipe 49. 15. The Pipers Weird 11. 74. The Strand Hornpipe 50. 75. The Dundee Hornpipe 50. Barndances 13. 76. Silver Star Hornpipe 51. 16. Scott Skinner's Compliments To Dr.MacDonald 14. 77. Fisher's Hornpipe 51. 17. The Inverness Gathering 15. 78. The Gypsie's Hornpipe 52. 18. Dornoch Links #2 15. 79. -

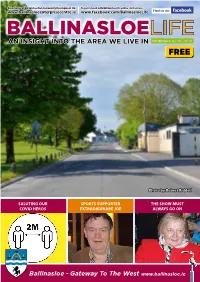

Ballinasloe, Co. Galway

An initiative of Ballinasloe Area Community Development Ltd. To get in touch with Ballinasloe Life online, visit us here: www.ballinasloeenterprisecentre.ie www.facebook.com/BallinasloeLife AN INSIGHT INTO THE AREA WE LIVE IN Vol. 10 Issue 2: Jun' ‘20 - Jul' ‘20 Photo by Robert Riddell SALUTING OUR SPORTS SUPPORTER THE SHOW MUST COVID HEROS EXTRAORDINARE JOE ALWAYS GO ON Ballinasloe - Gateway To The West www.ballinasloe.ie Gullane’s Hotel & CONFERENCE CENTRE Due to the exceptional circumstances we are all in, we are not in a position currently to confirm reopening date. We will continue to update you on the progress. We would like to acknowledge the hard work of all those on the front line and thank you all for continued support. Tomas and Caroline Gullane Main Street, Ballinasloe, Co. Galway T: 090 96 42220 F: 090 96 44395 E: [email protected] Visit our website gullaneshotel.com REAMHRA Welcome to Volume 10 issue 2 Welcome to our June / July 2nd COVID Lockin Edition, if the As we are going to print, the 1 metre versus 2 metre ding dong Magazine 8 weeks ago was challenging this was surreal. bobbles along – signalling that the vested economic interest In our efforts to offer a record of what is happening, occurred and groups have made their sacrifice for the common good and want what is planned we have relied a little bit more on memories past to go back to normality. and larger than usual profiles. It has not quite dawned on some of us that there is no going They say you don’t know what you have until it’s gone but truth is back – there is coping, living with, adapting and improving how we all knew exactly what we had; we just never thought we were we can live in these pandemic times. -

1 APPENDICES Table of Contents 1. Appendix 1

APPENDICES Table of Contents 1. Appendix 1 .................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Love ....................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. Emotional colouring ....................................................................................... 6 1.1.2. Change of meaning ....................................................................................... 14 1.1.3. The moment of speaking ............................................................................... 16 1.1.4. Temporariness ............................................................................................... 18 1.1.5. Repetition ...................................................................................................... 19 1.1.6. Duration ........................................................................................................ 19 1.1.7. A matter of course ......................................................................................... 25 1.1.8. Immediacy in a generic statement ................................................................ 26 1.2. Like ...................................................................................................................... 26 1.2.1. Politeness, tentativeness ................................................................................ 26 1.2.2. Emotional colouring .................................................................................... -

Bessemer, Michigan

60 percent chance of rain and snow High: 43 | Low: 35 | Details, page 2 DAILY GLOBE yourdailyglobe.com Friday, October 18, 2013 75 cents Mercer residents AUTUMN REFLECTIONS Wording for McDonald question Aging Unit board recall petition approved By RALPH ANSAMI would be next May. n Claim two [email protected] In her second effort to BESSEMER — The Gogebic approve language for the bal- members have County Election Commission lot, Graham alleged: served past term Thursday approved language —McDonald misled voters, limits for a ballot on whether Bill telling them to vote no on a M c D o n a l d bond issue and to vote for plan By KATIE PERTTUNEN should be B, when there was no plan B. [email protected] recalled from —Disregarded the school HURLEY — Iron County’s the Bessemer district’s bidding process by Aging Unit board heard from School Board. giving out premature informa- two Mercer residents at its Sheri Gra- tion to a contractor without the Thursday morning meeting at ham, a fellow board’s knowledge. the senior center. school mem- —Used foul language at Victor Ouimette claimed two ber who is board meetings, even though board members are serving in attempting to being warned not to do so by violation of a Wisconsin statute, oust McDon- board presidents. past their six-year term limits, ald from Bill All three allegations were which calls everything the board office, will McDonald included in Graham’s first does into question. “There is no now have 180 effort to get recall language right way to do a wrong thing,” days to collect signatures for a Ouimette said. -

Cinemagic Dublin Virtual Festival

CINEMAGIC DUBLIN VIRTUAL FESTIVAL 2021 cinemagic.ie Welcome to Cinemagic Dublin, an exciting online programme of screenings, CINEMAGIC DUBLIN SUMMER SCREENING PROGRAMME workshops, masterclasses and film juries. AVAILABLE ON THE CINEMAGIC FESTIVAL PLAYER WELCOME We have programmed a contemporary season of the very best film content for FILMFESTIVAL.CINEMAGIC.ORG.UK CLICK HERE FOR young audiences to enjoy from home. ALL RENTALS FESTIVAL TRAILER €3 (IRE) / £3 (UK) FROM 16TH – 29TH JULY STREAMING (IN IRELAND & UK) KIWI + STRIT IRISH PREMIERE The two funny and furry little creatures Kiwi and Strit live in a clearing in the forest. Kiwi is considerate, Dir: Esben Toft Jacobsen / careful and yellow, while Strit is wild and purple Denmark / 2021 / 37 mins / Age: All / No Dialogue and they have very different approaches to almost everything. But they are both very playful and curious. The two best friends discover new places that allow for new adventures and friendships. Join them on a series of hilarious adventures as they A MESSAGE OF SUPPORT find themselves in trouble over and The Department of Education is delighted to continue its support for the Dublin over again! Cinemagic International Film and Television Festival in 2021. Since 2008, the festival has provided a unique opportunity for young people to view new film from around the world and to gain an insight into the world of film-making and to learn from industry professionals through participation in masterclasses and workshops. Cinemagic initiatives provide young people from both jurisdictions on the island of Ireland with unique opportunities to engage and interact with each other, based on their shared interests in film and the creative industries. -

The Wild Geese 5 Charities Supported by the Sale of This Song Book

geese25 Wild Geese 25th Anniversary Charity Song Book 2016 This charity song book includes an eclectic mix of songs sung over the last 25 years (1992-2016) by members of the band and their friends in numerous bars throughout Ireland and beyond... Long may they be sung ...And ‘long may they run... ...all songs are copyright of their respective owners Published 2016 Page: CONTENTS Page: CONTENTS 4 A brief history of the Wild Geese 5 Charities supported by the sale of this song book Song: Chosen by / for: Song: Chosen by / for: 6 Absent friends Norman Wylie 40 Liberty’s sweet shore Rob Watkins 7 Across the great divide Lindsay Leonard 41 Motherland Kath Wylie 8 Amarillo Dick Stamp 42 Outlaw Blues Brian Parsons 9 American pie John Baines 43 Paddy & the bricks Brian Wylie 10 Ballad of Bina McLoughlin Justine McGreal Hafferty 44 Paddy lay back David Brown 11 Bang on the ear Mitch France 45 Paddy on the railway Brendan Hafferty 12 Black velvet band Brian Wylie 46 Paradise Mick McLoughlin 13 Carrickfergus Ian McDonald 47 Peaceful easy feeling Peter Moran 14 Dead flowers Rob Watkins 48 Raglan road Paul Copley 15 Dear old Donegal Brian Hafferty 49 Red haired Mary Michael Hafferty 16 Desperados waiting for a train Pat Fadden 50 Riley’s daughter Andrew Jackson 17 Dirty old town Paul Copley 51 Rocky road to Dublin Ciaran Hafferty 18 Down by the sally gardens John Boyle 52 Running bear John Booth 19 Dream a little dream Gillian Gibbons 53 She moved through the fair John Boyle 20 Dublin in the rare ould times Eugene Owens 54 Shoals of herring Peter -

The Wedding Karen Bies

The Wedding Karen Bies English translation: Trevor Scarse The Wedding Sunday morning 8 April Ids is lying next to me, still sleeping. We’ve been together since last night. It was the third time we met in The Rose where people we knew from school (Noel and Jane) and some regular musicians were playing. The piano of The Rose is old but still in tune, so Ids was playing on it all night. Brendan asked me if I wanted to sing ‘Galway Shawl’ and later on I did a rendition of ‘Beautiful’ by Christina A., together with Jane. It felt liberating. Singing helped, together with the sounds made by the piano and the knowledge that Ids was there. We snogged outside for a long time and he walked me home without asking. We drank the last of the bottle of red wine I still had from my birthday. Ids laid down beside me with his head in my lap. He is a great kisser and his piano hands are so soft yet strong at the same time. I was a little bit tipsy, but not too drunk to forget what I was doing, you know? Ids. Ids, I hope. Please PLEASE. Dear diary, I write this to reassure myself that he’s for real. Xxx Thursday 12 April A dress must be found, and I had to tag along. Bah. I have exams next week but mum is Quite fond of traditions so I couldn’t get out of it. She’d rather have taken grandma with her, but that is no longer possible. -

Washington Label Discography

Washington Label Discography: Washington 300 series (12 inch LP) WLP 301 - Tom Glaser Concert (For and with Children) – Tom Glazer [10/59] Jimmie Crack Corn/Jennie Jenkins/Skip to My Lou/Fox/Put Your Finger in the Air/Hush Little Baby/Pick a Bale/Names/Come On and Join Into the Game/Little Bitty Baby/Now, Now, Now/Frog/So Long WLP 302 – Come See the Peppermint Tree – Evelyn Lohoefer and Evelyn and Donald. McKayle [1959] Follow Me/Kitchen Stuff/My Shoes Went Walking/The Yellow Bee/Jabberty-Jib/The Elf/A Shiny Penny/Putt-Putt/My Pretty Red Swing/Riddle/Dance Awhile//Jump and Spin/Riding on a Star/Me, Too/Wheels/All Mixed Up/Miriam/The Dress/The Ribbon/Carrots and Things/The Crow, The Worm and The Fish/The Moon in the Yard/Thingamabob/The Peppermint Tree/Mr. Sandman WLP 303 – Sometime-Anytime – McKayle, Stephenson, Reynolds [1959] Parade/Stuff/Watching Things Go By/Gingerbread Man/Red Wagon/Squirrel/Lunch in the Yard/Wiggle-Fidget/Not Quite Sure/Tree House/Limb of a Bright Blue Tree/Balloon/Please/Rocking Chair/Quite a Day/Rooster With a Purple Head Washington Classical 400 series (12 inch LP) WLP 401 - Beethoven: Short Piano Works - Arthur Balsam [1958] WLP 402 - Vivaldi-Telemann - New York Woodwind Quintet [1958] WLP 403 - Telemann: Don Quichotte - Newell Jenkins and Milan Chamber Orchestra [1958] WLP 404 - Vivaldi: 4 Conceri - Newell Jenkins and Milan Chamber Orchestra [1958] WLP 405 - Torelli: Sinfonias - Newell Jenkins and Milan Chamber Orchestra [1958] WLP 406 - Vivaldi: Violin Concerto, 3 Winds Concerti - Newell Jenkins and Milan Chamber