Buruli Ulcer in Southern Côte D'ivoire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

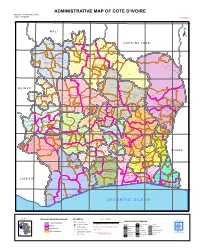

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

5 Geology and Groundwater 5 Geology and Groundwater

5 GEOLOGY AND GROUNDWATER 5 GEOLOGY AND GROUNDWATER Table of Contents Page CHAPTER 1 PRESENT CONDITIONS OF TOPOGRAPHY, GEOLOGY AND HYDROGEOLOGY.................................................................... 5 – 1 1.1 Topography............................................................................................................... 5 – 1 1.2 Geology.................................................................................................................... 5 – 2 1.3 Hydrogeology and Groundwater.............................................................................. 5 – 4 CHAPTER 2 GROUNDWATER RESOURCES POTENTIAL ............................... 5 – 13 2.1 Mechanism of Recharge and Flow of Groundwater ................................................ 5 – 13 2.2 Method for Potential Estimate of Groundwater ....................................................... 5 – 13 2.3 Groundwater Potential ............................................................................................. 5 – 16 2.4 Consideration to Select Priority Area for Groundwater Development Project ........ 5 – 18 CHAPTER 3 GROUNDWATER BALANCE STUDY .............................................. 5 – 21 3.1 Mathod of Groundwater Balance Analysis .............................................................. 5 – 21 3.2 Actual Groundwater Balance in 1998 ...................................................................... 5 – 23 3.3 Future Groundwater Balance in 2015 ...................................................................... 5 – 24 CHAPTER -

Economic and Climate Effects of Low-Carbon Agricultural And

ISSN 2521-7240 ISSN 2521-7240 7 7 Economic and climate effects of low-carbon agricultural and bioenergy practices in the rice value chain in Gagnoa, Côte d’Ivoire FAO AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS TECHNICAL STUDY DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS AGRICULTURAL FAO 7 Economic and climate effects of low-carbon agricultural and bioenergy practices in the rice value chain in Gagnoa, Côte d’Ivoire By Florent Eveillé Energy expert, Climate and Environment Division (CBC), FAO Laure-Sophie Schiettecatte Climate mitigation expert, Agricultural Development Economics Division (ESA), FAO Anass Toudert Consultant, Agricultural Development Economics Division (ESA), FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2020 Required citation: Eveillé, F., Schiettecatte, L.-S. & Toudert, A. 2020. Economic and climate effects of low-carbon agricultural and bioenergy practices in the rice value chain in Gagnoa, Côte d’Ivoire. FAO Agricultural Development Economics Technical Study 7. Rome, FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb0553en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

Working Paper Series 2020

International Development ISSN 1470-2320 Working Paper Series 2020 No.20-200 Push, Pull, and Push-back to Land Certification: Regional dynamics in pilot certification projects in Côte d'Ivoire Professor Catherine Boone Published: March 2020 Department of International Development London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street Tel: +44 (020) 7955 7425/6252 London Fax: +44 (020) 7955-6844 WC2A 2AE UK Email: [email protected] Website: www.lse.ac.uk/InternationalDevelopment 1 Push, Pull, and Push-back to Land Certification: Regional dynamics in pilot certification projects in Côte d'Ivoire by CATHERINE BOONE, Professor Department of Government, London School of Economics (LSE) Connaught House 604, Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE, UK. [email protected] with Pr. Brice Bado, Assistant Professor Aristide Mah Dion, Master's en Droits Humaines 2020 Zibo Irigo, Master's en Droits Humaines 2020 CERAP, Centre des Etudes et d'Action pour la Paix (Institution Universitaire Jésuite) Cocody, Blvd. Mermoz, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire 2 Abstract Since 2000, many African countries have moved toward land tenure reforms that aim at comprehensive land registration (or certification) and titling. Much work in political science and in the advocacy literature identifies recipients of land certificates or titles as "program beneficiaries," and political scientists have modeled titling programs as a form of distributive politics. In practice, however, land registration programs are often divisive and difficult to implement. This paper tackles the apparent puzzle of friction around land certification. We study Côte d'Ivoire's rocky history of land certification from 2004 to 2017 to identify political economy variables that may give rise to heterogenous and even conflicting preferences around certification. -

Côte D'ivoire

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT HOSPITAL INFRASTRUCTURE REHABILITATION AND BASIC HEALTHCARE SUPPORT REPUBLIC OF COTE D’IVOIRE COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION MARCH-APRIL 2000 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS, WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES, SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS BASIC DATA AND PROJECT MATRIX i to xii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND DESIGN 1 2.1 Project Objectives 1 2.2 Project Description 2 2.3 Project Design 3 3. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 3 3.1 Entry into Force and Start-up 3 3.2 Modifications 3 3.3 Implementation Schedule 5 3.4 Quarterly Reports and Accounts Audit 5 3.5 Procurement of Goods and Services 5 3.6 Costs, Sources of Finance and Disbursements 6 4 PROJECT PERFORMANCE AND RESULTS 7 4.1 Operational Performance 7 4.2 Institutional Performance 9 4.3 Performance of Consultants, Contractors and Suppliers 10 5 SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT 11 5.1 Social Impact 11 5.2 Environmental Impact 12 6. SUSTAINABILITY 12 6.1 Infrastructure 12 6.2 Equipment Maintenance 12 6.3 Cost Recovery 12 6.4 Health Staff 12 7. BANK’S AND BORROWER’S PERFORMANCE 13 7.1 Bank’s Performance 13 7.2 Borrower’s Performance 13 8. OVERALL PERFORMANCE AND RATING 13 9. CONCLUSIONS, LESSONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 9.1 Conclusions 13 9.2 Lessons 14 9.3 Recommendations 14 Mrs. B. BA (Public Health Expert) and a Consulting Architect prepared this report following their project completion mission in the Republic of Cote d’Ivoire on March-April 2000. -

Study of the Biomass Potential in Côte D'ivoire

Study of the biomass potential in Côte d'Ivoire Commissioned by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency Sector study Waste-based Biomass in Côte d’Ivoire RVO project ref. 202009047 / PST20CI02 Study of the biomass potential in Côte d'Ivoire Final Report Marius Guero / Bregje Drion / Peter Karsch | Partners for Innovation | 4 June 2021 Contact persons: Mrs. E. Bindels (RVO) and Mr. J. Kouame (EKN Côte d’Ivoire) Toyola cookstoves – Ghana [photo Toyola] Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of the study ........................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Study outline........................................................................................................................ 1 1.4 Guidance for the reader ...................................................................................................... 2 2. Approach of the inventory and selection of productive use cases................................ 3 2.1 Context ................................................................................................................................ 3 2.2 Approach of the inventory .................................................................................................. 3 2.3 Methodology to identify, assess and select the -

Epidemiology of Intestinal Parasite Infections in Three Departments of South-Central Côte D'ivoire Before the Implementation

Parasite Epidemiology and Control 3 (2018) 63–76 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Parasite Epidemiology and Control journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/parepi Epidemiology of intestinal parasite infections in three departments of south-central Côte d’Ivoire before the implementation of a T cluster-randomised trial Gaoussou Coulibalya,b,c,d, Mamadou Ouattaraa,b,KouassiDongob,e, Eveline Hürlimannc,d, Fidèle K. Bassaa,b,NaférimaKonéa,ClémenceEsséb,f,RichardB.Yapia,b,BassirouBonfohb,c, ⁎ Jürg Utzingerc,d, Giovanna Rasoc,d, , Eliézer K. N’Gorana,b a Unité de Formation et de Recherche Biosciences, Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire b Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire c Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland d University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland e Unité de Formation et de Recherche Sciences de la Terre et des Ressources Minières, Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire f Unité de Formation et de Recherche Sciences Sociales, Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Hundreds of millions of people are infected with helminths and intestinal protozoa, particularly Côte d’Ivoire children in low- and middle-income countries. Preventive chemotherapy is the main strategy to Integrated control control helminthiases. However, rapid re-infection occurs in settings where there is a lack of Intestinal protozoa clean water, sanitation and hygiene. In August and September 2014, we conducted a cross-sec- Sanitation and hygiene tional epidemiological survey in 56 communities of three departments of south-central Côte Schistosomiasis d’Ivoire. Study participants were invited to provide stool and urine samples. -

2018 CLCCG Annual Report

CLCCG ANNUAL REPORT U.S. Representative Eliot Engel U.S. Department of Labor Government of Côte d’Ivoire Government of Ghana International Chocolate and Cocoa Industry The United States Department of Labor is responsible only for the content it provided for this report. The material provided by other signatories to the Declaration of Joint Action to Support Implementation of the Harkin-Engel Protocol does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Department of Labor, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. Photo Credit: World Cocoa Foundation ACRONYMS………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….....ii CONGRESSIONAL QUOTE………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...1 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 REPORT FOR THE GOVERNMENT OF CÔTE D’IVOIRE (FRENCH)….…………………………………………..………………..9 REPORT FOR THE GOVERNMENT OF GHANA…………………………………………………………………………………….…..17 REPORT FOR THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR………………………………………………………………...……….………...34 REPORT FROM WORLD COCOA FOUNDATION ON COCOAACTION…………………………………………………………39 APPENDIX 1: DECLARATION………………………………………………………………………………….………………………..……..49 APPENDIX 2: FRAMEWORK…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….50 APPENDIX 3: BY-LAWS……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………..57 i ACRONYMS ACE Action against Child Exploitation ANADER National Agency for Rural Development Support/l’Agence Nationale d’Appui au Développement Rural AHTU Anti-Trafficking Unit of -

Côte D'ivoire

Niger 8° 7° 6° 5° 4° 3° CÔTE D’IVOIRE The boundaries and names shown and CÔTE the designations used on this map do Sikasso BURKINA National capital D’IVOIRE not imply official endorsement or Regional capital acceptance by the United Nations Bobo-Dioulasso e FASO r Town i 11° Diebougou o 11° Orodara Major airport N B a t a International boundary l MALI g o o L e V e Regional boundary r Banfora a b Main road a Tingrela Railroad Gaoua Goueya San Sokoro kar ani Katoro Kaoura 10° Maniniam Zinguinasso Ouangolodougou 10° Korohara Samatiguila Banda B ma l SAVANES B Bobanie a DENGUELE l c a Moromoro k n Madinani c V Gbeleba o Odienne l Boundiali Ferkessedougou t a I T Seguelo Korhogo r i i e n n g b a Fasselemon o Bouna u GUINEA Bako Paatogo Kiemou Tafire 9° 9° B Gawi Siraodi ou Kineta Fadyadougou Lato M Kakpin a Bandoli Koro r Sonozo a a Kafine oa/Bo Kani h VALLEE DU B o ZANZAN u e Dabakala Boudouyo Santa Touba WORODOUGOU BANDAMA Tanbi BAFING Nandala Mankono Katiola Diaradougou Bondoukau 8° Foungesso 8° C Seguela a v Tanda a Glanle Biankouma Toumbo l l y Beoumi Bouake DIX-HUIT MONTAGNES Zuenoula Sakassou M'Bahiacro Koun Man Vavoua Ba Sunyani Danane N’ZI COMOE HAUT Agnibilekrou Bangolo Daoukro 7° SASSANDRA Bouafle LACS MOYEN 7° COMOE Binhouye Daloa MARAHOUE Yamoussoukro Duekoue Abengourou Dimbokro Sinfra Guiglo Bougouanou Toulepleu Issia Toumodi GHANA Oume MOYENCAVALLY Bebou FROMAGER a i o Zagne Gribouo Gagnoa AGNEBY B n a Tchien Adzope T 6° 6° Agboville Tai Lakota Divo Tiassale Soubre SUD Gueyo SUD BANDAMA COMOE B LIBERIA o u LAGUNES b Aboisso Niebe o Abidjan Grand-Lahou Fish Town BAS SASSANDRA Attoutou Grand-Bassam Braffedon 5° Gazeko 5° Grabo N o n Sassandra o GULF O F GUINEA Barclayville Olodio San-Pedro 0 30 60 90 km Grand Béréby Harper 0 30 60 mi Tabou ATLANTIC OCE A N 8° 7° 6° 5° 4° 3° Map No. -

Issue 4, 2011

IS S U E 4 , 2 0 1 1 ct4|2011 contents EDITORIAL 2 by Vasu Gounden FEATURES 3 Imperatives for Post-conflict Reconstruction in Libya by Ibrahim Sharqieh 11 ‘Mediation with Muscles or Minds?’ Lessons from a Conflict-sensitive Mediation Style in Darfur by Allard Duursma 20 The Necessary Conditions for Post-conflict Reconciliation by Karanja Mbugua 28 Côte d’Ivoire’s Post-conflict Challenges by David Zounmenou 38 Comparing Approaches to Reconciliation in South Africa and Rwanda by Cori Wielenga 46 Post-amnesty Programme in the Niger Delta: Challenges and Prospects by Oluwatoyin O. Oluwaniyi BOOk REvIEw 55 The Enough Moment: Fighting to End Africa’s Worst Human Rights Crimes Reviewed by Linda M. Johnston conflict trends I 1 editorial byS vA u gouNDEN The year 2011 will certainly go down in history as a governments increasingly unable to provide for their basic watershed year, dominated by political and economic needs. Our major challenge is to craft an economic and upheavals and natural disasters. It will be remembered for political system that will deliver potable water, food, fuel, the collapse of several regimes in North Africa that were housing, healthcare, education, transport, security and other once thought to be unshakeable. It was the year in which basic needs equitably to all people. several developed nations in Europe faced bankruptcy. All these challenges confront us at a time when trade, It was also the year in which Japan experienced a massive transport and telephony connect the world like at no other earthquake and a devastating tsunami, which dangerously time in the history of mankind. -

Floristic Diversity and Fruit Species Potential in Cocoa Agroecosystems in the Department of Daloa, Côte D'ivoire

Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. (2021). 8(7): 171-182 International Journal of Advanced Research in Biological Sciences ISSN: 2348-8069 www.ijarbs.com DOI: 10.22192/ijarbs Coden: IJARQG (USA) Volume 8, Issue 7 -2021 Research Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22192/ijarbs.2021.08.07.020 Floristic diversity and fruit species potential in cocoa agroecosystems in the department of Daloa, Côte d'Ivoire *AMON Anoh Denis-Esdras1, KOUASSI Kouadio Claude1, SORO Kafana2, KOUAKOU Kouassi Jean-Luc1, SORO Dodiomon3 and TRAORE Dossahoua3 1Université Jean Lorougnon Guédé, UFR Agroforesterie. BP 150 Daloa, Côte d’Ivoire. 2Centre de Recherche d’Ecologie, Université Nangui Abrogoua (CRE/UNA). 08 BP 109 Abidjan 08, Côte d’Ivoire 3Laboratoire de Botanique, UFR Biosciences, Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny. 22 BP 582 Abidjan 22, Côte d’Ivoire * Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract Agroforestry systems with cocoa trees are full of important woody resources, including fruit species that provide various products for human needs. Despite their importance, unfortunately, these systems are experiencing a progressive reduction in fruit species under the combined effect of climate change and anthropic pressures. The sustainability of fruit trees in cocoa agro-ecosystems necessarily requires knowledge of their floristic diversity, hence the interest in evaluating the potential of fruit species in these ecological environments. The methods of surface surveys of 50m x 50m (2500 m2) and itinerant was adopted for the inventories in 8 cocoa farms in 4 localities of the department of Daloa and a survey carried out among farmers provided information on fruit species. A total of 63 fruit species, divided into 48 genera belonging to 31 families were inventoried. -

Côte D'ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire Risk-sensitive Budget Review UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction UNDRR Country Reports on Public Investment Planning for Disaster Risk Reduction This series is designed to make available to a wider readership selected studies on public investment planning for disaster risk reduction (DRR) in cooperation with Member States. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) Country Reports do not represent the official views of UNDRR or of its member countries. The opinions expressed and arguments employed are those of the author(s). Country Reports describe preliminary results or research in progress by the author(s) and are published to stimulate discussion on a broad range of issues on DRR. Funded by the European Union Front cover photo credit: Anouk Delafortrie, EC/ECHO. ECHO’s aid supports the improvement of food security and social cohesion in areas affected by the conflict. Page i Table of contents List of figures ....................................................................................................................................ii List of tables .....................................................................................................................................iii List of acronyms ...............................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgements ...........................................................................................................................v Executive summary .........................................................................................................................