Issue 4, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Ascendance Is/As Moral Rightness: the New Religious Political Right in Post-Apartheid South Africa Part

Economic Ascendance is/as Moral Rightness: The New Religious Political Right in Post-apartheid South Africa Part One: The Political Introduction If one were to go by the paucity of academic scholarship on the broad New Right in the post-apartheid South African context, one would not be remiss for thinking that the country is immune from this global phenomenon. I say broad because there is some academic scholarship that deals only with the existence of right wing organisations at the end of the apartheid era (du Toit 1991, Grobbelaar et al. 1989, Schönteich 2004, Schönteich and Boshoff 2003, van Rooyen 1994, Visser 2007, Welsh 1988, 1989,1995, Zille 1988). In this older context, this work focuses on a number of white Right organisations, including their ideas of nationalism, the role of Christianity in their ideologies, as well as their opposition to reform in South Africa, especially the significance of the idea of partition in these organisations. Helen Zille’s list, for example, includes the Herstigte Nasionale Party, Conservative Party, Afrikaner People’s Guard, South African Bureau of Racial Affairs (SABRA), Society of Orange Workers, Forum for the Future, Stallard Foundation, Afrikaner Resistance Movement (AWB), and the White Liberation Movement (BBB). There is also literature that deals with New Right ideology and its impact on South African education in the transition era by drawing on the broader literature on how the New Right was using education as a primary battleground globally (Fataar 1997, Kallaway 1989). Moreover, another narrow and newer literature exists that continues the focus on primarily extreme right organisations in South Africa that have found resonance in the global context of the rise of the so-called Alternative Right that rejects mainstream conservatism. -

Plant a Tree

ADDRESS BY THE MINISTER OF WATER AFFAIRS & FORESTRY, RONNIE KASRILS, AT A TREE PLANTING IN MEMORY OF THE MURDER OF THE GUGULETHU SEVEN & AMY BIEHL Arbor Day, Gugulethu, 31st August 1999 I am very honoured to have this opportunity to greet you all. And today I want to extend a special message to all of you who experienced the terrible events that happened here in Gugulethu in the apartheid years. And also, after the disaster that struck early on Sunday morning, the great losses you are suffering now. I am here today in memory and in tribute of all the people of Gugulethu. I salute the courage you have shown over the years. And I want to express my deep sympathy and concern for the plight of those who have lost their family and friends, their homes and their property in the last few days. This commemoration has been dedicated to eight people. Eight people who were senselessly slaughtered right here in this historical community. The first event took place at about 7.30 in the morning on 3 March 1986 when seven young men were shot dead at the corner of NY1 and NY111 and in a field nearby. There names were Mandla Simon Mxinwa, Zanisile Zenith Mjobo, Zola Alfred Swelani, Godfrey Miya, Christopher Piet, Themba Mlifi and Zabonke John Konile. All seven were shot in the head and suffered numerous other gunshot wounds. Every one here knows the story of how they were set up by askaris and drove into a police trap. Just seven and a half years later, on 25 August 1993, Amy Elizabeth Biehl drove into Gugulethu to drop off some friends. -

31 May 1995 CONSTITUTIONAL ASSEMBLY NATIONAL

31 May 1995 CONSTITUTIONAL ASSEMBLY NATIONAL WORKSHOP AND PUBLIC HEARING FOR WOMEN - 2-4 JUNE 1995 The Council's representative at the abovementioned hearing will be Mrs Eva Mahlangu, a teacher at the Filadelfia Secondary School for children with disabilities, Eva has a disability herself. We thank you for the opportunity to comment. It is Council's opinion that many women are disabled because of neglect, abuse and violence and should be protected. Further more Women with Disabilities are one of the most marginalised groups and need to be empowered to take their rightful place in society. According to the United Nations World Programme of Action Concerning Disable Persons: "The consequences of deficiencies and disablement are particularly serious for women. There are a great many countries where women are subjected to social, cultural and economic disadvantages which impede their access to, for example, health care, education, vocational training and employment. If, in addition, they are physically or mentally disabled their chances of overcoming their disablement are diminished, which makes it all the more difficult for them to take part in community life. In families, the responsibility for caring for a disabled parent often lies with women, which considerably limits their freedom and their possibilities of taking part in other activities". The Nairobi Plan of Action for the 1990's also states: Disabled women all over the world are subject to dual discrimination: first, their gender assigns them second-class citizenship; then they are further devalued because of the negative and limited ways the world perceives people with disabilities. Legislation shall guarantee the rights of disabled women to be educated and make decisions about pregnancy, motherhood, adoption, and any medical procedure which affects their ability to reproduce. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Traces of Truth

TRACES OF TRUTH SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) CONTENTS 1. PREHISTORY OF THE TRC 3 1.1 ARTICLES 3 1.2 BOOKS AND BOOK CHAPTERS 5 1.3 THESES 6 2. HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS 7 2.1 ARTICLES 7 2.2 BOOKS AND BOOK CHAPTERS 10 2.3 THESES 12 3. AMNESTY 13 3.1 ARTICLES 13 3.2 BOOKS AND BOOK CHAPTERS 14 3.3 THESES 16 4. REPARATIONS AND REHABILITATION 17 4.1 ARTICLES 17 4.2 BOOKS AND BOOK CHAPTERS 18 4.3 THESES 19 5. AFTERMATH 20 5.1 ARTICLES 20 5.2 BOOKS AND BOOK CHAPTERS 33 5.3 THESES 40 6. ONLINE RESOURCES 44 7. AUDIOVISUAL COLLECTIONS 45 Select TRC bibliography compiled by Historical Papers (University of Witwatersrand) and South African History Archive (November 2006) 2 1. PREHISTORY OF THE TRC Includes: • Prehistory • Establishment of the TRC • Early perceptions and challenges 1.1 ARTICLES Abraham, L. Vision, truth and rationality, New Contrast 23, no. 1 (1995). Adelman, S. Accountability and administrative law in South Africa's transition to democracy, Journal of Law and Society 21, no. 3 (1994):317-328. Africa Watch. South Africa: Accounting for the past. The lessons for South Africa from Latin America, Human Rights Watch (23 October 1992). Barcroft, P.A. The presidential pardon - a flawed solution, Human Rights Law Journal 14 (1993). Berat, L. Prosecuting human rights violations from a predecessor regime. Guidelines for a transformed South Africa, Boston College Third World Law Journal 13, no. 2 (1993):199-231. Berat, L. & Shain, Y. -

4 Chapter Four: the African Ubuntu Philosophy

4 CHAPTER FOUR: THE AFRICAN UBUNTU PHILOSOPHY A person is a person through other persons. None of us comes into the world fully formed. We would not know how to think, or walk, or speak, or behave as human beings unless we learned it from other human beings. We need other human beings in order to be human. (Tutu, 2004:25). 4.1 INTRODUCTION Management practices and policies are not an entirely internal organisational matter, as various factors beyond the formal boundary of an organisation may be at least equally influential in an organisation’s survival. In this study, society, which includes the local community and its socio-cultural elements, is recognised as one of the main external stakeholders of an organisation (see the conceptual framework in Figure 1, on p. 7). Aside from society, organisations are linked to ecological systems that provide natural resources as another form of capital. As Section 3.5.13 shows, one of the most important limitations of the Balanced Scorecard model is that it does not integrate socio-cultural dimensions into its conceptual framework (Voelpel et al., 2006:51). The model’s perspectives do not explicitly address issues such as the society or the community within which an organisation operates. In an African framework, taking into account the local socio-cultural dimensions is critical for organisational performance and the ultimate success of an organisation. Hence, it is necessary to review this component of corporate performance critically before effecting any measures, such as redesigning the generic Balanced Scorecard model. This chapter examines the first set of humanist performance systems, as shown in Figure 11, overleaf. -

One Nation, One Beer: the Mythology of the New South Africa in Advertising

1 ONE NATION, ONE BEER: THE MYTHOLOGY OF THE NEW SOUTH AFRICA IN ADVERTISING A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg Sarah Britten 2 I declare that this is my own unaided work. It is in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted for any other degree or examination or to any other university. ________________ Sarah Britten 27 October 2005 The University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 3 Acknowledgements Since I started on this thesis, I have worked at four jobs (one in PR, three in advertising), dated two boyfriends (one of them a professional psychic), published two novels for young adult readers, endured two car accidents (neither of them my fault), rescued two feral cats and married one husband. I ha ve lost count of the nervous breakdowns I was convinced were immanent or the Sunday evenings I spent wracked with guilt over my failure to put in enough work on the thesis over the weekend. When I started on this project in June 1998, I was a full time student wafting about without any apparent purpose in life. Now that I am finally putting this magnum opus to bed, I find that I have turned into a corporate animal saddled with car payments and timesheets and stress over PowerPoint presentations. “Get your PhD out of the way before you get married and have kids,” my elders told me. -

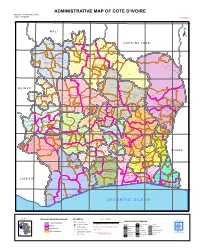

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

5 Geology and Groundwater 5 Geology and Groundwater

5 GEOLOGY AND GROUNDWATER 5 GEOLOGY AND GROUNDWATER Table of Contents Page CHAPTER 1 PRESENT CONDITIONS OF TOPOGRAPHY, GEOLOGY AND HYDROGEOLOGY.................................................................... 5 – 1 1.1 Topography............................................................................................................... 5 – 1 1.2 Geology.................................................................................................................... 5 – 2 1.3 Hydrogeology and Groundwater.............................................................................. 5 – 4 CHAPTER 2 GROUNDWATER RESOURCES POTENTIAL ............................... 5 – 13 2.1 Mechanism of Recharge and Flow of Groundwater ................................................ 5 – 13 2.2 Method for Potential Estimate of Groundwater ....................................................... 5 – 13 2.3 Groundwater Potential ............................................................................................. 5 – 16 2.4 Consideration to Select Priority Area for Groundwater Development Project ........ 5 – 18 CHAPTER 3 GROUNDWATER BALANCE STUDY .............................................. 5 – 21 3.1 Mathod of Groundwater Balance Analysis .............................................................. 5 – 21 3.2 Actual Groundwater Balance in 1998 ...................................................................... 5 – 23 3.3 Future Groundwater Balance in 2015 ...................................................................... 5 – 24 CHAPTER -

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I Would

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to record and extend my indebtedness, sincerest gratitude and thanks to the following people: * Mr G J Bradshaw and Ms A Nel Weldrick for their professional assistance, guidance and patience throughout the course of this study. * My colleagues, Ms M M Khumalo, Mr I M Biyela and Mr L P Mafokoane for their guidance and inspiration which made the completion of this study possible. " Dr A A M Rossouw for the advice he provided during our lengthy interview and to Ms L Snodgrass, the Conflict Management Programme Co-ordinator. " Mrs Sue Jefferys (UPE) for typing and editing this work. " Unibank, Edu-Loan (C J de Swardt) and Vodakom for their financial assistance throughout this work. " My friends and neighbours who were always available when I needed them, and who assisted me through some very frustrating times. " And last and by no means least my wife, Nelisiwe and my three children, Mpendulo, Gabisile and Ntuthuko for their unconditional love, support and encouragement throughout the course of this study. Even though they were not practically involved in what I was doing, their support was always strong and motivating. DEDICATION To my late father, Enock Vumbu and my brother Gcina Esau. We Must always look to the future. Tomorrow is the time that gives a man or a country just one more chance. Tomorrow is the most important think in life. It comes into us very clean (Author unknow) ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF ABBREVIATIONS/ ACRONYMS USED ANC = African National Congress AZAPO = Azanian African Peoples -

Economic and Climate Effects of Low-Carbon Agricultural And

ISSN 2521-7240 ISSN 2521-7240 7 7 Economic and climate effects of low-carbon agricultural and bioenergy practices in the rice value chain in Gagnoa, Côte d’Ivoire FAO AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS TECHNICAL STUDY DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS AGRICULTURAL FAO 7 Economic and climate effects of low-carbon agricultural and bioenergy practices in the rice value chain in Gagnoa, Côte d’Ivoire By Florent Eveillé Energy expert, Climate and Environment Division (CBC), FAO Laure-Sophie Schiettecatte Climate mitigation expert, Agricultural Development Economics Division (ESA), FAO Anass Toudert Consultant, Agricultural Development Economics Division (ESA), FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2020 Required citation: Eveillé, F., Schiettecatte, L.-S. & Toudert, A. 2020. Economic and climate effects of low-carbon agricultural and bioenergy practices in the rice value chain in Gagnoa, Côte d’Ivoire. FAO Agricultural Development Economics Technical Study 7. Rome, FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb0553en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

Governance and Development of the East African Community: the Ethical Sustainability Framework

Governance and Development of the East African Community: The Ethical Sustainability Framework Dickson Kanakulya Faculty of Arts and Sciences Studies in Applied Ethics 16 Linköping University, Department of Culture and Communication Linköping 2015 Studies in Applied Ethics 16 Distributed by: Department of Culture and Communication Linköping University 581 83 Linköping Sweden Dickson Kanakulya Governance and Development of the East African Community: The Ethical Sustainability Framework Licentiate thesis Edition 1:1 ISSN 1402‐4152:16 ISBN 978‐91‐7685‐894‐3 © The author Department of Culture and Communication 2015 Declaration: I declare that this study is my original work and a product of my personal critical research and thought. …………………………………………….. Kanakulya Dickson, Kampala, Uganda November, 2015 ii Approval: This research report has been submitted with the approval of my supervisor: Prof. Goran Collste --2015--11--09----- Co-Supervisor’s name: Signature: Date iii © 2015 Kanakulya Dickson All rights reserved iv Dedication: This work is dedicated to the Lord of all Spirits and Letters; accept it as a feeble effort to serve your eternal purposes.To Caroline Kanakulya, a beautiful and kindred spirit. To the healing of the spirit of East Africans.To the watchers who stood steadfast in the days of the multiplication. Great mysteries await across! v Acknowledgements: I acknowledge the Swedish Agency for International Development (Sida) and Makerere University for funding this research; and the staff of Makerere Directorate of Graduate Research and Training for support during the study. My deepest gratitude goes to my wife Caroline Kanakulya, my travel companion in life’s journey; thanks for standing my flaws and supporting me.