The Politics of Power and Public Space the Politics Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Training Schedule 2018.Xlsx

Training Schedule for Successful Hajj Applicants of Government Hajj Scheme - 2018 Sr. No. District Date Venue Time Training Arranged By JALAL BABA AUDITORIUM, Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 1 ABBOTTABAD 25-Mar-18 09 AM ABBOTTABAD 9247521, 9247575 JALAL BABA AUDITORIUM, Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 2 ABBOTTABAD 26-Mar-18 09 AM ABBOTTABAD 9247521, 9247575 PARADISE MARRIAGE HALL, MAIN Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 3 ATTOCK 28-Mar-18 09 AM RAWALPINDI ROAD, FATEH JANG 9247521, 9247575 TULIP MARQUE, CHINA CHOWK, Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 4 ATTOCK 03-Apr-18 09 AM HAJI SHAH ROAD, ATTOCK 9247521, 9247575 Hajj Complex, Quetta, Ph: (081) 5 AWARAN 19-Apr-18 DISTRICT COUNCIL HALL, PANJGUR 09 AM 9213021, 9213326 QATAR MASJID, HYDERABAD Hajji Camp, Karachi, Ph: (021) 6 BADIN 28-Mar-18 10 AM ROAD, BADIN 99204761, 35688307 MILAN MARRIEGE CLUB, SUGER 7 BAHAWAL NAGAR 02-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 MILL ROAD,CHISHTIAN 8 BAHAWAL NAGAR 03-Apr-18 OFFICERS CLUBE FORT ABBAS 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 INSAF MARRIAGE HALL OPPOSITE TABLEEGHI MARKAN 9 BAHAWAL NAGAR 04-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 HAROONABAD ROAD , BAHAWAL NAGHAR MILAN MARRIEGE CLUB, SUGER 10 BAHAWALPUR 02-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 MILL ROAD,CHISHTIAN QUAID-E-AZAM MEDICAL 11 BAHAWALPUR 06-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 COLLEGE, BAHAWAL PUR. QUAID-E-AZAM MEDICAL 12 BAHAWALPUR 07-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 COLLEGE, BAHAWAL PUR. -

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Islamic Republic of Pakistan

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Islamic Republic of Pakistan NEPRA Tower, Attaturk Avenue (East), G-511, Islamabad Ph: +92-51-9206500, Fax: +92-51-2600026 Web: www.nepra.org.pk, E-mail: [email protected] No. NEPRA/ADG(L)/LAN-2187/ / 6 Y 2 1- (3 September 17 2019 Mr. Zafar Aitmad Siddique, R-3, Block-1, Gulistan-e-Johar, Karachi, Phone No. 0301-8258533 Subject: Generation Licence No. DGL/2187/2019 Licence Application No. LAN-2187 Mr. Zafar Aitmad Siddique, K — Electric Limited Ref KEL's letter No. KE/BPR/NEPRA/2019/624 dated 23.07.2019 (received on 29.07.2019) Enclosed please find herewith Generation Licence No. DGL/2187/2019 granted by the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority to Mr. Zafar Aitmad Siddique for 05.20 kW photo voltaic solar based distributed generation facility located at R-3, Block-1, Gulistan-e-Johar, Karachi, under NEPRA (Alternative & Renewable Energy) Distributed Generation and Net Metering Regulations, 2015. 2. Please quote above mentioned Generation ence No. for future correspondence. Enclosure: Generation Licence (DGL/2187/2019) CA (Syed Safeer Hussain) Copy to: 1. Chief Executive Office, Alternative Energy Development Board, 2nd Floor, OPF Building, G-5/2, Islamabad. 2. Chief Executive Officer, K-Electric Limited, KE House, 39 B, Main Sunset Boulevard, DHA Phase-II, Karachi. 3. Director General, Environment Protection Department, Government of Sindh, Complex Plot No. ST-2/1, Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi. National Electric Power f equlatory Authority NEP Is! mabad— kistan The Authority hereby grants Generation Licence to Mr. Zafar Aitvpad Siddique, for 5.20 KW photovoltaic solar based distributed generation facility, having consumer reference number LA912022, located at R-3, Block-I, Gulistan-e- Jouhar, Karachi under the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (Alternative & Renewable Energy) Distributed Generation and Net Metering Regulations, 2015 (the "A&RE Regulations") for a period of seven (07) years. -

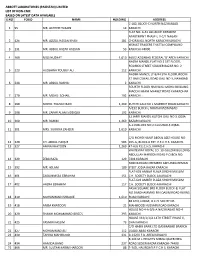

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

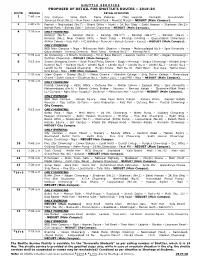

Shuttle Route

SHUTTLE SERVICES PROPOSED OF DETAIL FOR SHUTTLE’S ROUTES – 2019-20 ROUTE TIMINGS DETAIL OF ROUTES 1 7:40 a.m City Campus – Jama Cloth – Radio Pakistan – 7Day Hospital – Numaish – Gurumandir – Jamshed Road (No.3) – New Town – Askari Park – Mumtaz Manzil – NEDUET (Main Campus). 2 7:40 a.m Paposh – Nazimabad (No.7) – Board Office – Hydri – 2K Bus Stop – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman (No.2)– Namak Bank – Sohrab Goth – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 4 7:20 a.m ONLY MORNING: Korangi (No.5) – Korangi (No.4) – Korangi (No.31/2) – Korangi (No.21/2) – Korangi (No.2) – Korangi (No.1, Near Chakra Goth) – Nasir Jump – Korangi Crossing – Qayyumabad Chowrangi – Akhtar Colony – Kala Pull – FTC Building – Nursery – Baloch Colony – Karsaz – NEDUET (Main Campus). ONLY EVENING: NED Main Campus – Nipa – Millennium Mall– Stadium – Karsaz – Mehmoodabad No.6 – Iqra University – Qayyumabad – Korangi Crossing – Nasir Jump – Korangi No.21/2 – Korangi No.5. 5 7:45 a.m 4K Chowrangi – 2 Minute Chowrangi – 5C-4 (Bara Market) – Saleem Centre – U.P Mor – Nagan Chowrangi – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 6 7:15 a.m Shama Shopping Centre – Shah Faisal Police Station – Bagh-e-Korangi – Singer Chowrangi – Khaddi Stop – Korangi No.5 – Korangi No.6 – Landhi No.6 – Landhi No.5 – Landhi No.4 – Landhi No.3 – Landhi No.1 – Landhi No.89 – Dawood Chowrangi – Murghi Khana – Malir No.15 – Malir Hault – Star Gate – Natha Khan – Drig Road – Nipa – NED Main Campus. 7 7:35 a.m Islam Chowk – Orangi (No.5) – Metro Cinema – Abdullah College – Ship Owner College – Qalandarya Chowk – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman No.1 – Buffer Zone – Fazal Mill – Nipa – NEDUET (Main Campus). -

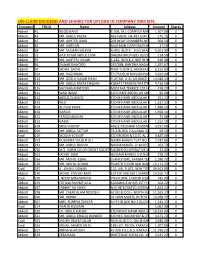

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

Site Name City a & Y Filling Station Karachi AFTAB SERVICE STATION

Site Name City A & Y Filling Station Karachi AFTAB SERVICE STATION Karachi AHMED FILLING STATION Karachi AHMED FILLING STATION ORANGI Karachi AISHA SERVICE STATION Karachi Al - Ayaan Filling Station Karachi Al Raheem Filling Station Karachi AL-KARIM SERVICE STATION Karachi Almas Filling Station Karachi AL-RAFAY SERVICE STATION Karachi AL-SAEED SERVICE STATION Karachi AL-SIDDIQUE SVC STN Karachi AMMA SERVICE STATION Karachi Arafat Filling Station Karachi ASAD PETROLEUM SERVICE Karachi Atrium Petroleum and CNG Services Karachi AWAN BALOUCH TRUCKING STATION Karachi Babar Filling Station Karachi Beachview Filling Station Karachi Bismillah Associates Karachi Burraq Filling Station Karachi CENTRAL GASOLINE Karachi Central Gasoline II Filling Station Karachi Chairman Service Station Karachi Chinar Filling Station Karachi CNG SYSTEMS Karachi Data Filling Station Karachi Enchante' Filling Station-COCO Karachi ESSA PETROLEUM Karachi Excel Petroleum Service Karachi FAISAL SERVICE STATION Karachi FARZAM FUEL STATION Karachi GOTEWALA SERVICE STATION Karachi GULSHAN SERVICE STATION Karachi HAFIZ SUDAIS FILLING STATION Karachi HIGH SPEED SERVICE STATION Karachi Hub Filling Station Karachi Jannat Filling Station Karachi JAVED SERVICE STATION Karachi Jinnah Petroleum Karachi KAMAL SERVICE STATION Karachi KARIMI AUTOS Karachi KHAWAR SHAHEED SERVICE STATION Karachi Khazan Associates Karachi KHYBER PETROL SERVICE Karachi Lavender Filling Station Karachi LUCKY SERVICE STATION Karachi M/s. Madina Filing Station Karachi Madni Filling Station Karachi MAKKAH AUTOS Karachi Malir Filling Station Karachi Mashallah Associates Karachi MILLAT SERVICE STATION Karachi Mina Filling Station Karachi MM FILLING STATION Karachi Moon Filling Station Karachi NAVEED TRUCKING Karachi New Korangi Filling Station Karachi NEW TOWN FUEL STATION Karachi NORTHERN GASOLINE Karachi QASIM SERVICE STATION Karachi RAJA 2 PETROLEUM Karachi RAJA SERVICE STATION Karachi Reda Filling Station Karachi Rehman Filling Station Karachi REX SERVICE STATION Karachi RM FILLING STATION Karachi S. -

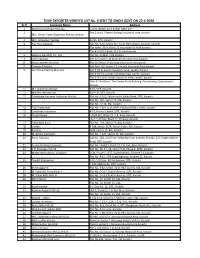

TDAP EXPORTER VERIFIED LIST No. 9 SENT to SINDH GOVT on 22-4-2020 Sr.# Company Name Address 1 Multinational Export Bureau L-10 D, BLOCK 22, F B IND

TDAP EXPORTER VERIFIED LIST No. 9 SENT TO SINDH GOVT ON 22-4-2020 Sr.# Company Name Address 1 Multinational Export Bureau L-10 D, BLOCK 22, F B IND. AREA KHI 2 Plot 2 and 17 Sector Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi M/s. United Towel Exporters Private Limited 3 M/s. Homecare Textiles D-115, SITE, Karachi 4 Five Star Apparels Plot No. E-92, Sector No. 31-D, P&T Society, Korangi, Karachi. Plot No# L-33/A, Block 22 Industrial F.B Area Karachi Plot # LA 8/19 Block 22 F.B Area Karachi 5 Lakhany Silk Mills Pvt. Ltd. Plot No. D/48-D, SITE Karachi 7 Vista Apparels Plot 6/1, Sector 15 Korangi Industrial Area Karachi 8 Nova Leathers (Pvt) Ltd Plot 30 Sector 15 Korangi Industrial Area Karachi 9 Threads & Motifs Plot No# 126, Sector 15, Korangi Industrial Area Karachi 10 Gul Ahmed Textile Mills Ltd Plot # HT-8, Landhi Industrial Area, Landhi, Karachi Plot # HT-19, Landhi Industrial Area, Landhi, Karachi Plot # H-5, H-6, Landhi Industrial Area, Landhi, Karachi 16th & 23rd Floor, The Center Point Building, Expressway, Qayyumabad, Karachi 11 M.I. Industries (Dying) B-45, SITE, Karachi. 12 Mahee International F/413-B, SITE, Karachi. 13 Cambridge Garment Industries Pvt Ltd. Plot No. A-5/1, Fakharuddin Valika Road, SITE, Karachi. Plot No. 102, Sector 27, KIA, Karachi. Plot No. C-124, KIA, Karachi. 14 ZIQI Enterprises Plot No. 2 & 9, A-VI, KEPZ, PO Box18700, Landhi, Karachi. 15 Combined Industries A-15, Binoria Chowk, SITE, Karachi. 16 Globe Dyeing L-26/B & C, Block 22, F.B. -

Branch Directory

Dubai Islamic Bank - Branch Directory Abbottabad S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Khyber 1 31 Abbottabad CB 306/4, Lala Rukh Plaza, Mansehra Road, Abbottabad, Pakhtunkhwa 0992-342239-41 Ground Floor, Shop Nos.12 & 13, Mamu Jee Market, Opp GPO, Cantt Khyber 2 161 Abbottabad 2 Bazaar, Abbottabad, Pakhtunkhwa 0992-342394 Attock S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Plot No B-1-63, A Block, Khan Plaza, Fawara Chowk, Civil Bazaar, Attock. 3 73 Attock Punjab. Punjab 057-2702054-6 Mehria Town Housing Scheme, Phase 1, Shop No. 25 + 39, Block - A, Kamra 4 187 Mehria Road - Attock Punjab Bahawalpur S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Model Town Plot No 12.B, Khewat No 148,Khatooni No.246,General Officer Colony, 062-2889951-3, 5 71 Bahawalpur Model Town B, Bahawalpur,Punjab. Punjab 2889961-3 Burewala S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number 439/EB, Block C, Al-Aziz Super Market, College Road, Burewala. Vehari 6 95 Burewala District, Punjab. Punjab 067-3772388 Chakwal S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, No. 1636, Khewat 323, Opposite Main PTCL Office Main 7 172 Chakwal Talagang Road, Chakwal District, Punjab. Punjab 054-3544115 Chaman S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, Haji Ayub Plaza, Plot No. Mall Road, Chaman.Killa Abdullah 8 122 Chaman District, Balochistan . Balochistan 0826-61806-61812 Dadyal S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, Khasra No. 552, Moza Mandi, Kacheri Road, Dadyal, District Azad Jammu & 9 120 Dadyal Mirpur Azad Jammu Kashmir. -

City Location Type Address Abbotabad ABBOTABAD BRANCH

City Location Type Address Abbotabad ABBOTABAD BRANCH ATM Shop # 841,Farooqabad Mansehra Road,Abbottabad Ahmed Pur Ahmed Pur Easr ATM 22, Dera Nawab Road, Adjacent Civil Hospital, Ahmed Pur, Arifwala ARIFWALA BRANCH ATM 173-D Thana Bazar Arifwala.Multan Attock Attock ATM Faysal Bank Limited Plot # 169 Shaikh jaffar plaza Saddiqui road Attock city Azad Kashmir Mir Akbar Plaza AK ATM Akbar Plaza, Plot No.2, Sector A/2, Mirpur, Azad Kashmir Bahawalnagar Bahawalnagar ATM Shop # 02 Ghalla Mandi ,Bahawalnagar Bahawalpur NOOR MAHALROAD BR.H ATM 2 - Rehman Society, Noor Mahal Road, Bahawalpur IBB Circular Road Bahawalpur ATM IBB Circular Road Bahawalpur Bahawalpur Yazman Mandi ATM 56/A-DB Bahawalpur Road Bannu Bannu ATM Khasra No. 1462/1833, Mouza Fatima Khel, Near Durrani Plaza, Ex GTS Chowk, Bannu Cantt., Bannu. Bhalwal BHALWAL-1 ATM Liaqat Shaheed Road Tehsil Bhalwal Distt Surghodha Bhalwal branch Burewala BUREWALA BRANCH ATM 95-C, Multan Road, Burewala chakwal Chakwal ATM FBL-Talha gang road, opposite Alliace travel, chakwal. Charsadda Islamic Branch - Charsadda ATM Ground Floor, Gold Mines Towers, Noweshera Road, Charsadda Cheechawatni CHEECHAWATNI BRANCH ATM G.T Road Chichawatni Cheshtian Cheshtian ATM 143 B - Block Main Bazar Cheshtian D.I. Khan IBB D.I.Khan ATM No.19, Survey No.79, Near GPO Chowk, East Circular Road, D.I. Khan Cantt. Depalpur DEPALPUR RD. OKARA ATM Shop # 1& 2,Khewat # 1822,Khatooni 2930 To 2940,Gillani Heights,Madina Chowk Dera Ghazi Khan DGK-JAMPUR ROAD ATM Pakistan Plaza, Jampur Road, Dera Ghazi Khan. Dudial Dudial ATM Hussain Shopping Centre, Main Bazar Branch, Dudial, Azad Kashmir. -

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of BQPS-III 900 MW RLNG Based Combined Cycle Power Plant Karachi, Pakistan

K-Electric Limited Environmental & Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of BQPS-III 900 MW RLNG Based Combined Cycle Power Project (BQPS-III RLNG CCPP). Final Report Environmental and June, 2017 Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of BQPS-III 900 MW RING Based Combined Cycle Power Plant Global Environmental Management Services (Pvt.) Ltd. Z"“1 Floor, Aiwan-e-Sanat, ST-4/2, Sector 23, Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi (BQPS-III RLNG CCPP). GEMS Ph: (92-21) 35113804-5; Fax: (92-21) 35113806; Email: [email protected] Global Environmental Management Services (Pvt.) Ltd. 2nd Floor, Aiwan-e-Sanat, ST-4/2, Sector 23, Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi GEMS Rh: (92-21) 35113804-5; Fax: (92-21) 35113806; Email; [email protected] Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of BQPS-III 900 MW RLNG Based Combined Cycle Power Plant Karachi, Pakistan ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANT'S PROFILE AND INTRODUCTION ES Global Environmental Management Services (Pvt.) Ltd. (GEMS) is an Environmental EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Consultancy which provides broad range of Environmental Solutions which are and not GEMS limited to Environmental Audits, Initial Environmental Examinations (IEE), Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIA), Baseline studies and Training & Capacity building. GEMS is one of the few environmental firm having its own renowned ISO 17025 OVERVIEW Certified Environmental Laboratory by the name of Global Environmental Laboratory (Pvt) Ltd. Study Type BACKGROUND INFORMATION AND NEED ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA). PROJECT Study Title ESIA of BQPS-III 900 MW RLNG Based Combined Cycle Power Project Pakistan is in the midst of a severe energy crisis that largely stemmed from mismanagement of natural (BQPS-III RING CCPP). -

CBD First National Report

Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................... 5 GLOSSARY ............................................................................................................................................ 6 LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................................. 8 LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................ 9 LIST OF BOXES .................................................................................................................................. 10 PAKISTAN FACT SHEET ................................................................................................................. 11 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 12 1. PREPARATION OF THIS REPORT ........................................................................................ 15 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................... 16 1.1.1 What is Biodiversity? ...................................................................................................... 16 1.1.2 The Convention on Biological Diversity ......................................................................... 17 1.1.3 Pakistan’s Obligations................................................................................................... -

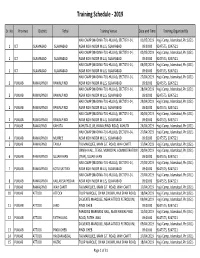

Training Schedule - 2019

Training Schedule - 2019 Sr. No Province District Tehsil Training Venue Date and Time Training Organized By HAJI CAMP (MADINA-TUL-HUJJAJ), SECTOR I-14, 01/05/2019 Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 1 ICT ISLAMABAD ISLAMABAD NEAR KOHI NOOR MILLS, ISLAMABAD 09:00:00 9247575, 9247521 HAJI CAMP (MADINA-TUL-HUJJAJ), SECTOR I-14, 02/05/2019 Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 1 ICT ISLAMABAD ISLAMABAD NEAR KOHI NOOR MILLS, ISLAMABAD 09:00:00 9247575, 9247521 HAJI CAMP (MADINA-TUL-HUJJAJ), SECTOR I-14, 03/05/2019 Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 1 ICT ISLAMABAD ISLAMABAD NEAR KOHI NOOR MILLS, ISLAMABAD 09:00:00 9247575, 9247521 HAJI CAMP (MADINA-TUL-HUJJAJ), SECTOR I-14, 27/04/2019 Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 2 PUNJAB RAWALPINDI RAWALPINDI NEAR KOHI NOOR MILLS, ISLAMABAD 09:00:00 9247575, 9247521 HAJI CAMP (MADINA-TUL-HUJJAJ), SECTOR I-14, 28/04/2019 Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 2 PUNJAB RAWALPINDI RAWALPINDI NEAR KOHI NOOR MILLS, ISLAMABAD 09:00:00 9247575, 9247521 HAJI CAMP (MADINA-TUL-HUJJAJ), SECTOR I-14, 29/04/2019 Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 2 PUNJAB RAWALPINDI RAWALPINDI NEAR KOHI NOOR MILLS, ISLAMABAD 09:00:00 9247575, 9247521 HAJI CAMP (MADINA-TUL-HUJJAJ), SECTOR I-14, 30/04/2019 Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 2 PUNJAB RAWALPINDI RAWALPINDI NEAR KOHI NOOR MILLS, ISLAMABAD 09:00:00 9247575, 9247521 3 PUNJAB RAWALPINDI KAHUTA KAHUTA CLUB, RAWALPINDI ROAD, KAHUTA 24/04/2019 Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) HAJI CAMP (MADINA-TUL-HUJJAJ), SECTOR I-14, 27/04/2019 Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 4 PUNJAB RAWALPINDI MURREE NEAR KOHI NOOR MILLS, ISLAMABAD 09:00:00 9247575, 9247521 5 PUNJAB RAWALPINDI TAXILA TAJ MARQUEE, MAIN G.T.