Hopton Heath Battlefield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseline Report Staffordshire Moorlands District Council

Cheadle Baseline Report Staffordshire Moorlands District Council S72(p)/ Baseline Report /September 2009/BE Group/Tel 01925 822112 Cheadle Baseline Report Staffordshire Moorlands District Council CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 2.0 CONTEXT ................................................................................................................. 3 3.0 TOWN CENTRE USES ........................................................................................... 26 4.0 LOCAL PROPERTY MARKET ................................................................................ 48 5.0 TOWNSCAPE ......................................................................................................... 55 6.0 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT ................................................................................... 75 7.0 OPPORTUNITY SITES ......................................................................................... 107 8.0 BASELINE TESTING WORKSHOPS .................................................................... 119 9.0 CONCLUSIONS AND NEXT STEPS .................................................................... 125 Appendix 1 – Use Classes Plan Appendix 2 – Retailer Survey Questionnaire Appendix 3 – Public Launch Comments Appendix 4 – Councillors Workshop Comments Appendix 5 – Stakeholder Workshop Comments S72(p)/ Baseline Report /September 2009/BE Group/Tel 01925 822112 Cheadle Baseline Report Staffordshire Moorlands District Council -

Old Heath Hayes' Have Been Loaned 1'Rom Many Aources Private Collections, Treasured Albums and Local Authority Archives

OLD HEATH HAVES STAFFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL. EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, LOCAL HISTORY SOURCE BOOK L.50 OLD HEATH HAVES BY J.B. BUCKNALL AND J,R, FRANCIS MARQU£SS OF' ANGl.ESEV. LORO OF' THE MAtt0R OF HEATH HAVES STAFFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL, EDUCATION DEPAR TMENT. IN APPRECIATION It is with regret that this booklet will be the last venture produced by the Staffordshire Authority under the inspiration and guidance of Mr. R.A. Lewis, as historical resource material for schools. Publi cation of the volume coincides with the retirement of Roy Lewis, a former Headteacher of Lydney School, Gloucestershire, after some 21 years of service in the Authority as County Inspector for History. When it was first known that he was thinking of a cessation of his Staffordshire duties, a quick count was made of our piles of his 'source books' . Our stock of his well known 'Green Books' (Local History Source Books) and 'Blue Books' (Teachers Guides and Study Books) totalled, amazingly, just over 100 volumes, ·a mountain of his torical source material ' made available for use within our schools - a notable achievement. Stimulating, authoritative and challenging, they have outlined our local historical heritage in clear and concise form, and have brought the local history of Staffordshire to the prominence that it justly deserves. These volumes have either been written by him or employed the willing ly volunteered services of Staffordshire teachers. Whatever the agency behind the pen it is obvious that forward planning, correlation of text and pictorial aspects, financial considerations for production runs, organisation of print-run time with a busy print room, distri bution of booklets throughout Staffordshire schools etc. -

The Implementation and Impact of the Reformation in Shropshire, 1545-1575

The Implementation and Impact of the Reformation in Shropshire, 1545-1575 Elizabeth Murray A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts United Faculty of Theology The Melbourne College of Divinity October, 2007 Abstract Most English Reformation studies have been about the far north or the wealthier south-east. The poorer areas of the midlands and west have been largely passed over as less well-documented and thus less interesting. This thesis studying the north of the county of Shropshire demonstrates that the generally accepted model of the change from Roman Catholic to English Reformed worship does not adequately describe the experience of parishioners in that county. Acknowledgements I am grateful to Dr Craig D’Alton for his constant support and guidance as my supervisor. Thanks to Dr Dolly Mackinnon for introducing me to historical soundscapes with enthusiasm. Thanks also to the members of the Medieval Early Modern History Cohort for acting as a sounding board for ideas and for their assistance in transcribing the manuscripts in palaeography workshops. I wish to acknowledge the valuable assistance of various Shropshire and Staffordshire clergy, the staff of the Lichfield Heritage Centre and Lichfield Cathedral for permission to photograph churches and church plate. Thanks also to the Victoria & Albert Museum for access to their textiles collection. The staff at the Shropshire Archives, Shrewsbury were very helpful, as were the staff of the State Library of Victoria who retrieved all the volumes of the Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society. I very much appreciate the ongoing support and love of my family. -

47 Little Tixall Lane

Little Tixall Lane Great Haywood, Stafford, ST18 0SE Little Tixall Lane Great Haywood, Stafford, ST18 0SE A deceptively spacious family sized detached chalet style bungalow, occupying a very pleasant position within the sought after village of Great Haywood. Reception Hall with Sitting Area, Cloakroom, Lounge, Breakfast Kitchen, Utility, Conservatory, Dining Room, En Suite Bedroom, First Floor: Three Bedrooms, Bathroom Outside: Front and Rear Gardens, Drive to Garage Guide Price £300,000 Accommodation Reception Hall with Sitting Area having a front entrance door and built in cloaks cupboards. There is a Guest Cloakroom off with white suite comprising low flush w.c and wash basin. Spacious Lounge with two front facing windows to lawned front garden and a Regency style fire surround with coal effect fire, tiled hearth and inset. The Breakfast Kitchen has a range of high and low level units with work surfaces and a sink and drainer. Rangemaster range style oven with extractor canopy over. Off the kitchen is a Utility with space and provision for domestic appliances and the room also houses the wall mounted gas boiler. Conservatory having double French style doors to the side and a separate Dining Room with double doors opening from the kitchen, French style doors to the garden and stairs rising to the first floor. Bedroom with fitted bedroom furniture, double French style doors opening to the garden and access to the En Suite which has a double width shower, pedestal wash basin and low flush w.c. First Floor There are Three Bedrooms, all of which have restricted roof height in some areas, and also to part of the Bathroom which comprises bath, pedestal wash basin and low flush w.c. -

Great Haywood to Swynnerton

HS2: IN YOUR AREA Autumn 2015 – Great Haywood to Sywnnerton High Speed Two is the Government’s planned new, high speed railway. We (HS2 Ltd) are responsible for Edinburgh Glasgodesigningw and building the railway, and for making recommendations to the Government. HS2 station Between July 2013 and January 2014, we consulted the publicHS2 on destination served by HS2 classic compatible services the proposedWES route and stations for Phase Two of HS2, from the West T C O Phase One core high speed network A Midlands to SManchester, Leeds and beyond. The Government wants T MAIN part of Phase Two – the route between the West Midlands and CrewePhase Two– to core high speed network open in 2027, six yearsLIN ahead of the rest of Phase Two, so that the North E Phase Two ‘A’ core high speed network and Scotland will realise more benefits from HS2 as soon as possible. HS2 connection to existing rail network This factsheet is to updateCarlisle you aboutNewcast thele route between the West Midlands and Crewe. It explains: Classic compatible services • where the route goes and how it has changed since the consultation; • how to find more information Daaboutrlingto nproperty or construction issues; E A S T C • how to get in touch with us. O A For questions about HS2, call our S T MAIN Community Relations team on 020 7944 4908 ©HS2 Ltd/Bob Martin. LIN E Link to Link to West Coast East Coast The route from the Main Line Main Line York West Midlands to Crewe Leeds Preston The route from the West Midlands Wigan to Crewe forms the southern 37 miles Manchester Piccadilly (60 km) of the Manchester leg on the Warrington Phase Two network. -

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation Proposals for a new pattern of divisions Produced by Peter McKenzie, Richard Cressey and Mark Sproston Contents 1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 2 Approach to Developing Proposals.........................................................................1 3 Summary of Proposals .............................................................................................2 4 Cannock Chase District Council Area .....................................................................4 5 East Staffordshire Borough Council area ...............................................................9 6 Lichfield District Council Area ...............................................................................14 7 Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Area ....................................................18 8 South Staffordshire District Council Area.............................................................25 9 Stafford Borough Council Area..............................................................................31 10 Staffordshire Moorlands District Council Area.....................................................38 11 Tamworth Borough Council Area...........................................................................41 12 Conclusions.............................................................................................................45 -

Premises Licence List

Premises Licence List PL0002 Drink Zone Plus Premises Address: 16 Market Place Licence Holder: Jasvinder CHAHAL Uttoxeter 9 Bramblewick Drive Staffordshire Littleover ST14 8HP Derby Derbyshire DE23 3YG PL0003 Capital Restaurant Premises Address: 62 Bridge Street Licence Holder: Bo QI Uttoxeter 87 Tumbler Grove Staffordshire Wolverhampton ST14 8AP West Midlands WV10 0AW PL0004 The Cross Keys Premises Address: Burton Street Licence Holder: Wendy Frances BROWN Tutbury The Cross Keys, 46 Burton Street Burton upon Trent Tutbury Staffordshire Burton upon Trent DE13 9NR Staffordshire DE13 9NR PL0005 Water Bridge Premises Address: Derby Road Licence Holder: WHITBREAD GROUP PLC Uttoxeter Whitbread Court, Houghton Hall Business Staffordshire Porz Avenue ST14 5AA Dunstable Bedfordshire LU5 5XE PL0008 Kajal's Off Licence Ltd Premises Address: 79 Hunter Street Licence Holder: Rajeevan SELVARAJAH Burton upon Trent 45 Dallow Crescent Staffordshire Burton upon Trent DE14 2SR Stafffordshire DE14 2PN PL0009 Manor Golf Club LTD Premises Address: Leese Hill Licence Holder: MANOR GOLF CLUB LTD Kingstone Manor Golf Club Uttoxeter Leese Hill, Kingstone Staffordshire Uttoxeter ST14 8QT Staffordshire ST14 8QT PL0010 The Post Office Premises Address: New Row Licence Holder: Sarah POWLSON Draycott-in-the-Clay The Post Office Ashbourne New Row Derbyshire Draycott In The Clay DE6 5GZ Ashbourne Derbyshire DE6 5GZ 26 Jan 2021 at 15:57 Printed by LalPac Page 1 Premises Licence List PL0011 Marks and Spencer plc Premises Address: 2/6 St Modwens Walk Licence Holder: MARKS -

To Access Forms and Drawings Associated with the Applications

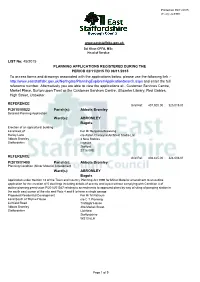

Printed On 09/11/2015 Weekly List ESBC www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk Sal Khan CPFA, MSc Head of Service LIST No: 45/2015 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED DURING THE PERIOD 02/11/2015 TO 06/11/2015 To access forms and drawings associated with the applications below, please use the following link :- http://www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk/Northgate/PlanningExplorer/ApplicationSearch.aspx and enter the full reference number. Alternatively you are able to view the applications at:- Customer Services Centre, Market Place, Burton upon Trent or the Customer Services Centre, Uttoxeter Library, Red Gables, High Street, Uttoxeter. REFERENCE Grid Ref: 407,920.00 : 325,015.00 P/2015/00822 Parish(s): Abbots Bromley Detailed Planning Application Ward(s): ABROMLEY Bagots Erection of an agricultural building Land East of For Mr Benjamin Browning Harley Lane c/o Aaron Chetwynd Architect Studio Ltd Abbots Bromley 3 New Stables Staffordshire Ingestre Stafford ST18 0RE REFERENCE Grid Ref: 408,425.00 : 324,006.00 P/2015/01400 Parish(s): Abbots Bromley Planning Condition (Minor Material Amendment Ward(s): ABROMLEY Bagots Application under Section 73 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 for Minor Material amendment to an outline application for the erection of 5 dwellings including details of access and layout without complying with Condition 4 of outline planning permission P/2014/01047 relating to amendments to approved plans by way of siting of pumping station in the south east corner of the site and Plots 4 and 5 to have a single garage Proposed Residential Development -

Development Land at Lower Tean

Development Land Lower Tean, Staffordshire Development Land Uttoxeter Road, Lower Tean, Staffordshire, ST10 4LN An excellent opportunity to acquire a “greenfield” site of approximately 0.85 acre to build 6 houses in a village location backing onto agricultural land with good access to nearby towns, facilities and the wider road network. Two 4 bedroom detached houses and Four 3 bedroom semi detached houses Guide Price £400,000 Situation Planning The property is situated within the village, opposite the Dog and Partridge Inn, with access Detailed Planning Permission has been granted by Staffordshire Moorlands District Council to the site off Heath House Lane with a proposed private drive leading to the rear of the 6 dated 19th June 2017 for six dwellings including a new vehicular access from Heath House Lane. houses. Lower Tean is about 3 miles south of Cheadle, 6 miles west of Uttoxeter and 10 Copies of the actual consents are available from the Agents or directly off the Staffordshire miles east of Stoke on Trent on the A522. There is convenient access to the A50. which Moorlands website - http://publicaccess.staffsmoorlands.gov.uk using the reference connects the M1 and M6 motorways, at Blythe Bridge (4 miles) or Uttoxeter. SMD/2017/0151. There are fast inter city trains at Stoke and a local mostly hourly service at Blythe Bridge The Plans, Elevations and drawings reproduced in these details are not to scale and with the between Stoke and Derby. There are regular bus services between permission of ctd Architects who have prepared the drawings for the planning application. -

The Basset Family: Marriage Connections and Socio-Political Networks

THE BASSET FAMILY: MARRIAGE CONNECTIONS AND SOCIO-POLITICAL NETWORKS IN MEDIEVAL STAFFORDSHIRE AND BEYOND A THESIS IN History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS By RACHAEL HAZELL B. A. Drury University, 2011 Kansas City, Missouri THE BASSET FAMILY: MARRIAGE CONNECTIONS AND SOCIO-POLITICAL NETWORKS IN MEDIEVAL STAFFORDSHIRE AND BEYOND Rachael Hazell, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri- Kansas City, 2015 ABSTRACT The political turmoil of the eleventh to fourteenth centuries in England had far reaching consequences for nearly everyone. Noble families especially had the added pressure of ensuring wise political alliances While maintaining and acquiring land and wealth. Although this pressure would have been felt throughout England, the political and economic success of the county of Staffordshire, home to the Basset family, hinged on its political structure, as Well as its geographical placement. Although it Was not as subject to Welsh invasions as neighboring Shropshire, such invasions had indirect destabilizing effects on the county. PoWerful baronial families of the time sought to gain land and favor through strategic alliances. Marriage frequently played a role in helping connect families, even across borders, and this Was the case for people of all social levels. As the leadership of England fluctuated, revolts and rebellions called poWerful families to dedicate their allegiances either to the king or to the rebellion. Either way, during the central and late Middle Ages, the West Midlands was an area of unrest. Between geography, weather, invaders from abroad, and internal political debate, the unrest in Staffordshire Would create an environment Where location, iii alliances, and family netWorks could make or break a family’s successes or failures. -

Cannock Chase District)

9. Rugeley project area This product includes mapping licensed licensed mapping includes product This the with Survey from Ordnance Her of Controller the of permission copyright © Crown Office Majesty’s All rights right 2009. database and/or (RHECZs) zones character environment historic Map Rugeley 25: reserved. Licence number 100019422. number Licence reserved. 77 9.1 RHECZ 1 – Etchinghill & Rugeley suburban growth 9.1.1 Summary on the historic environment The zone is dominated by late 20th century housing and an associated playing field. Etchinghill itself survives as an area of unenclosed land dotted with trees representing the remnants of a heath which once dominated this zone. Map 26 shows the known heritage assets within the zone including a mound which was once thought to be a Bronze Age mound, but is probably geological in origin118. Horse racing was taking place by 1834, although 17th century documents refer to ‘foot- racing’ over a three mile course at Etching Hill119. By the late 19th century a rifle range had been established within the zone and the butts may survive as an earthwork upon Etchinghill. The zone lies within the Cannock Chase AONB. This product includes mapping data licensed from Ordnance Survey © Crown copyright and / or database right (2009). Licence no. 100019422 Map 26: The known heritage assets 118 Staffordshire HER: PRN 00995 119 Greenslade 1959b: 152 78 9.1.2 Heritage Assets Summary Table Survival The zone has been extensively disturbed by 1 development with the exception of Etchinghill. Potential The potential for surviving heritage assets 2 has been reduced in the areas of the housing. -

3232 the LONDON GAZETTE, 9Ra MARCH 1979

3232 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 9ra MARCH 1979 Forsbrook, Staffordshire Moorlands District, Stafford- (29) New diversion channels of the River Stour, near shire. Wilden, within the parish of Stourport-on-Severn, Wyre (5) River Erewr.Eh, from the downstream face of the B6018 Forest District, Hereford and Worcester. read bridge at Kirkby-in-Ashfteld, lo ejnsiing main (30) River Arrow at the new gauging station near Broom, river at Portland Farm, Pinxton, near Kirkby-in- within the parishes of Bidford-on-Avon, and Salford Ashficld, Ashfteld District, Nottinghamshire. Priors, Stratford-on-Avon District, Warwickshire. (6) River Trent near Tiltensor, within the parishes of (31) Horsbere Brook, from the upstream face of the road Bailaston and S^cne Rural, Stafford Borough, Stafford- bridge at Brockworth Road (Green Street) to existing shire. main river at Mill Bridge Hucclecote within the parishes (7) River Trent near Darlaston, within the parish of Stone of Brockworth, and Hucclecote, Tewkesbury Borough, Rural, Stafford Borough, Staffordshire. Gloucestershire. (8) River Trent near Sandon, within the parish of Salt (32) New Diversion channel of the Horsbere Brook to and Enson, Stafford Borough, Staffordshire. River Severn, near Abloads Court, within the parish of (9) River Sow near Tillington, Stafford, Stafford Borough, Longford, Tewkesbury Borough, Gloucestershire. St-dffordsh:rs. (33) New Diversion channels of the Horsbere Brook, near (10) River Trent near Hoo ML'I, within the parishes of Drymeadow Farm, within the parishes of Innsworth Colwich and Ingestre, Stafford Sorough, Staffordshire. and Longford, Tewkesbury Borough, Gloucestershire. (11) River Penk near Kinvaston, within the parishes of (34) River Little Avon, from the upstream face of the Penkridge and Stretton, South Staffordshire District, .