Iron, Steel and Swords Script - Page 1 Bloomeries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property

NFS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multipler Propertyr ' Documentation Form NATIONAL This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ____Iron and Steel Resources of Pennsylvania, 1716-1945_______________ B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________ ~ ___Pennsylvania Iron and Steel Industry. 1716-1945_________________ C. Geographical Data Commonwealth of Pennsylvania continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, J hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requiremerytS\set forth iri36JCFR PafrfsBOfcyid the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official Date / Brent D. Glass Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple -

Three Hundred Years of Assaying American Iron and Iron Ores

Bull. Hist. Chem, 17/18 (1995) 41 THREE HUNDRED YEARS OF ASSAYING AMERICAN IRON AND IRON ORES Kvn K. Oln, WthArt It can reasonably be argued that of all of the industries factors were behind this development; increased pro- that made the modern world possible, iron and steel cess sophistication, a better understanding of how im- making holds a pivotal place. Without ferrous metals purities affected iron quality, increased capital costs, and technology, much of the modem world simply would a generation of chemically trained metallurgists enter- not exist. As the American iron industry grew from the ing the industry. This paper describes the major advances isolated iron plantations of the colonial era to the com- in analytical development. It also describes how the plex steel mills of today, the science of assaying played 19th century iron industry serves as a model for the way a critical role. The assayer gave the iron maker valu- an expanding industry comes to rely on analytical data able guidance in the quest for ever improving quality for process control. and by 1900 had laid down a theoretical foundation for the triumphs of steel in our own century. 1500's to 1800 Yet little is known about the assayer and how his By the mid 1500's the operating principles of assay labo- abilities were used by industry. Much has been written ratories were understood and set forth in the metallurgi- about the ironmaster and the furnace workers. Docents cal literature. Agricola's Mtll (1556), in period dress host historic ironmaking sites and inter- Biringuccio's rthn (1540), and the pret the lives of housewives, miners, molders, clerks, rbrbühln (Assaying Booklet, anon. -

Henry Bessemer and the Mass Production of Steel

Henry Bessemer and the Mass Production of Steel Englishmen, Sir Henry Bessemer (1813-1898) invented the first process for mass-producing steel inexpensively, essential to the development of skyscrapers. Modern steel is made using technology based on Bessemer's process. Bessemer was knighted in 1879 for his contribution to science. The "Bessemer Process" for mass-producing steel, was named after Bessemer. Bessemer's famous one-step process for producing cheap, high-quality steel made it possible for engineers to envision transcontinental railroads, sky-scraping office towers, bay- spanning bridges, unsinkable ships, and mass-produced horseless carriages. The key principle is removal of impurities from the iron by oxidation with air being blown through the molten iron. The oxidation also raises the temperature of the iron mass and keeps it molten. In the U.S., where natural resources and risk-taking investors were abundant, giant Bessemer steel mills sprung up to drive the expanding nation's rise as a dominant world economic and industrial leader. Why Steel? Steel is the most widely used of all metals, with uses ranging from concrete reinforcement in highways and in high-rise buildings to automobiles, aircraft, and vehicles in space. Steel is more ductile (able to deform without breakage) and durable than cast iron and is generally forged, rolled, or drawn into various shapes. The Bessemer process revolutionized steel manufacture by decreasing its cost. The process also decreased the labor requirements for steel-making. Prior to its introduction, steel was far too expensive to make bridges or the framework for buildings and thus wrought iron had been used throughout the Industrial Revolution. -

Primary Mill Fabrication

Metals Fabrication—Understanding the Basics Copyright © 2013 ASM International® F.C. Campbell, editor All rights reserved www.asminternational.org CHAPTER 1 Primary Mill Fabrication A GENERAL DIAGRAM for the production of steel from raw materials to finished mill products is shown in Fig. 1. Steel production starts with the reduction of ore in a blast furnace into pig iron. Because pig iron is rather impure and contains carbon in the range of 3 to 4.5 wt%, it must be further refined in either a basic oxygen or an electric arc furnace to produce steel that usually has a carbon content of less than 1 wt%. After the pig iron has been reduced to steel, it is cast into ingots or continuously cast into slabs. Cast steels are then hot worked to improve homogeneity, refine the as-cast microstructure, and fabricate desired product shapes. After initial hot rolling operations, semifinished products are worked by hot rolling, cold rolling, forging, extruding, or drawing. Some steels are used in the hot rolled condition, while others are heat treated to obtain specific properties. However, the great majority of plain carbon steel prod- ucts are low-carbon (<0.30 wt% C) steels that are used in the annealed condition. Medium-carbon (0.30 to 0.60 wt% C) and high-carbon (0.60 to 1.00 wt% C) steels are often quenched and tempered to provide higher strengths and hardness. Ironmaking The first step in making steel from iron ore is to make iron by chemically reducing the ore (iron oxide) with carbon, in the form of coke, according to the general equation: Fe2O3 + 3CO Æ 2Fe + 3CO2 (Eq 1) The ironmaking reaction takes place in a blast furnace, shown schemati- cally in Fig. -

Comparative Properties of Wrought Iron Made by Hand Puddling and by the Aston Process

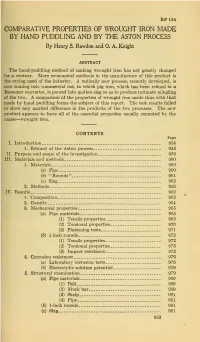

RP124 COMPARATIVE PROPERTIES OF WROUGHT IRON MADE BY HAND PUDDLING AND BY THE ASTON PROCESS By Henry S. Rawdon and 0. A. Knight ABSTRACT The hand-puddling method of making wrought iron has not greatly changed for a century. More economical methods in the manufacture of thjs product is the crying need of the industry. A radically new process, recently developed, is now coming into commercial use, in which pig iron, which h>as been refined in a Bessemer converter, is poured into molten slag so as to produce intimate mingling of the two. A comparison of the properties of wrought iron made thus with that made by hand puddling forms the subject of this report. The test results failed to show any marked difference in the products of the two processes. The new product appears to have all of the essential properties usually connoted by the name—wrought iron, CONTENTS Page I. Introduction 954 1. Resume of the Aston process 955 II. Purpose and scope of the investigation 959 III. Materials and methods 960 1. Materials 960 (a) Pipe 960 (6) "Rounds" 961 (c) Slag 962 2. Methods 962 IV. Results 962 1. Composition 962 2. Density 964 3. Mechanical properties 965 (a) Pipe materials 965 (1) Tensile properties 965 (2) Torsional properties 970 (3) Flattening tests 971 (6) 1-inch rounds 972 (1) Tensile properties 972 (2) Torsional properties 973 (3) Impact resistance 973 4. Corrosion resistance 976 (a) Laboratory corrosion tests 976 (6) Electrolytic solution potential 979 5. Structural examination 979 (a) Pipe materials 980 (1) BaU 980 (2) Muck bar 980 (3) Skelp 981 (4) Pipe 981 (&) 1-inch rounds 981 (c) Slag 981 953 : 954 Bureau of Standards Journal of Research [vol. -

Final Exam Questions Generated by the Class

Final Exam Questions Generated by the Class Module 8 – Iron and Steel Describe some of the business practices that Carnegie employed that allowed him to take command of the steel industry. Hard driving, vertical integration, price making Which of the following was/is NOT a method used to make steel? A. Puddling B. Bessemer process C. Basic oxygen process D. Arc melting E. None of the above What are the three forms of iron, and what is the associated carbon content of each? Wrought <.2% Steel .2-2.3% Cast Iron 2.3-4.2% How did Andrew Carnegie use vertical integration to gain control of the steel market? Controlled the entire steel making process from mining to final product Who created the best steel for several hundred years while making swords during the 1500’s? A. Syria B. Egypt C. Japan D. England Describe the difference between forging and casting. When forging, you beat and hammer the material into the desired shape. When casting, you pour liquid into a mold to shape it. Describe the difference between steel and wrought iron. Steel has less carbon Which of the following forms of iron has a low melting point and is not forgeable? A. Steel B. Pig Iron C. Wrought Iron D. None of the Above What two developments ushered in the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age? More iron ore and greater ability to change its properties using readily available alloying agent (carbon) 1 Final Exam Questions Generated by the Class What is the difference between ferrite and austenite? A. -

Ironworks and Iron Monuments Forges Et

IRONWORKS AND IRON MONUMENTS FORGES ET MONUMENTS EN FER I( ICCROM i ~ IRONWORKS AND IRON MONUMENTS study, conservation and adaptive use etude, conservation et reutilisation de FORGES ET MONUMENTS EN FER Symposium lronbridge, 23-25 • X •1984 ICCROM rome 1985 Editing: Cynthia Rockwell 'Monica Garcia Layout: Azar Soheil Jokilehto Organization and coordination: Giorgio Torraca Daniela Ferragni Jef Malliet © ICCROM 1985 Via di San Michele 13 00153 Rome RM, Italy Printed in Italy Sintesi Informazione S.r.l. CONTENTS page Introduction CROSSLEY David W. The conservation of monuments connected with the iron and steel industry in the Sheffield region. 1 PETRIE Angus J. The No.1 Smithery, Chatham Dockyard, 1805-1984 : 'Let your eye be your guide and your money the last thing you part with'. 15 BJORKENSTAM Nils The Swedish iron industry and its industrial heritage. 37 MAGNUSSON Gert The medieval blast furnace at Lapphyttan. 51 NISSER Marie Documentation and preservation of Swedish historic ironworks. 67 HAMON Francoise Les monuments historiques et la politique de protection des anciennes forges. 89 BELHOSTE Jean Francois L'inventaire des forges francaises et ses applications. 95 LECHERBONNIER Yannick Les forges de Basse Normandie : Conservation et reutilisation. A propos de deux exemples. 111 RIGNAULT Bernard Forges et hauts fourneaux en Bourgogne du Nord : un patrimoine au service de l'identite regionale. 123 LAMY Yvon Approche ethnologique et technologique d'un site siderurgique : La forge de Savignac-Ledrier (Dordogne). 149 BALL Norman R. A Canadian perspective on archives and industrial archaeology. 169 DE VRIES Dirk J. Iron making in the Netherlands. 177 iii page FERRAGNI Daniela, MALLIET Jef, TORRACA Giorgio The blast furnaces of Capalbio and Canino in the Italian Maremma. -

United States Patent Office 2,07,568 Process for Purfying

Patented Apr. 20, 1937 2,077,568 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE 2,07,568 PROCESS FOR PURFYING. FERROUS METALS Augustus B. Kinzel, Douglaston, N. Y., assignor, by mesne assignments, to Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation, a corporation of New York No Drawing. Application April 3, 1935, Serial No. 4440 2 Claims. (C. 75-60) The invention relates to the removal of oxidiz quently is had to stopping the blow as the end able impurities from ferrous metals by blowing point is approached and taking a coupon of the molten metal with an oxidizing blast, and has metal in order to determine by inspection its ap for its object the provision of means whereby proximate composition. But even this practice 5 control over the quality of the product may be leaves much to be desired, for the difficulty re- 5 greatly increased. mains of stopping the blow at exactly the right The method of the invention is particularly point during a necessarily short time interval. applicable to, and will be described in connection It WOuld therefore seem desirable to slow down with, the manufacture of steel by processes of the the end reactions by decreasing the blast rate as 10 Bessemer or converter type, wherein the oxida the end of the blow is approached; but in the ordi- 0 tion is customarily accomplished by means of an nary bottom blown converter this is impossible, air blast. W because a high blast rate is necessary in order It is generally believed that Bessemer steel is, to prevent the metal from running through the for some purposes, inferior in quality to steel bottom tuyeres. -

Manganese: Final Document Details

Datavägen 14B, 436 32, Askim, SWEDEN Telephone: +46 734 97 66 41 Email: [email protected] Website: www.hjedwardsaktiebolag.com Manganese Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn. It is not found as a free element in nature; it is often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy uses, particularly in stainless steels. www.hjedwardsaktiebolag.com Manganese is a silvery-gray metal that resembles iron. It is hard and very brittle, difficult to fuse, but easy to oxidize. Manganese metal and its common ions are paramagnetic. Manganese tarnishes slowly in air and oxidizes ("rusts") like iron in water containing dissolved oxygen. Manganese is part of the iron group of elements, which are thought to be synthesized in large stars shortly before the supernova explosion. Mn decays to Cr with a half-life of 3.7 million years. Because of its relatively short half-life, Mn is relatively rare, produced by cosmic rays impact on iron. Manganese isotopic contents are typically combined with chromium isotopic contents and have found application in isotope geology and radiometric dating. Mn–Cr isotopic ratios reinforce the evidence from Al and 1Pd for the early history of the solar system. Variations in 53Cr/52Cr and Mn/Cr 53 55 [email protected] ratios from several meteorites suggest an initial Mn/ Mn ratio, which indicates that Mn–Cr isotopic composition must result from in situ decay of 53Mn in differentiated planetary bodies. Hence, 53Mn provides additional evidence for nucleosynthetic processes immediately before coalescence of the solar system. -

History of Metallurgy

History of Metallurgy by Rochelle Forrester Copyright © 2019 Rochelle Forrester All Rights Reserved The moral right of the author has been asserted Anyone may reproduce all or any part of this paper without the permission of the author so long as a full acknowledgement of the source of the reproduced material is made. Second Edition Published 30 September 2019 Preface This paper was written in order to examine the order of discovery of significant developments in the history of metallurgy. It is part of my efforts to put the study of social and cultural history and social change on a scientific basis capable of rational analysis and understanding. This has resulted in a hard copy book How Change Happens: A Theory of Philosophy of History, Social Change and Cultural Evolution and a website How Change Happens Rochelle Forrester’s Social Change, Cultural Evolution and Philosophy of History website. There are also philosophy of history papers such as The Course of History, The Scientific Study of History, Guttman Scale Analysis and its use to explain Cultural Evolution and Social Change and Philosophy of History and papers on Academia.edu, Figshare, Humanities Commons, Mendeley, Open Science Framework, Orcid, Phil Papers, SocArXiv, Social Science Research Network, Vixra and Zenodo websites. This paper is part of a series on the History of Science and Technology. Other papers in the series are The Invention of Stone Tools Fire The Neolithic Revolution The Invention of Pottery History -

FERROALLOYS by Michael D

FERROALLOYS By Michael D. Fenton Domestic survey data and tables were prepared by Jo-Ann S. Sterling, statistical assistant, and international survey data and table were prepared by Glenn J. Wallace, international data coordinator. Ferroalloys are alloys of iron that contain one or more other production have fluctuated, but have been relatively strong chemical elements. These alloys are used to add these other (Sibley and others, 2001, p. 33). elements into molten metal, usually in steelmaking. The top six In the major ferroalloys and probably some specialty ferroalloy producers in the world in 2001, in decreasing order, ferroalloys, alternative materials to ferroalloys use, principally were China, South Africa, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Norway, and alloy scrap and oxide, overall have gained moderately on Russia. Ferroalloys impart distinctive qualities to steel or cast ferroalloys use per ton of steel production during the past 20 iron or serve important functions during the production cycle. years. A decline in unit consumption is significant during the The ferroalloy industry is closely associated with the iron and long term for the ferroalloy industry because such a decline steel industry, its largest customer. World production in 2001 moderates any increases in ferroalloy consumption resulting of the bulk ferroalloys chromium, manganese, and silicon, was from greater steel production. Conversely, it exacerbates any estimated at 18.8 million metric tons (Mt), a 3.6% decrease decreases. A combination of factors, including technology, compared with that of 2000. U.S. bulk ferroalloy reported availability, and price, is responsible for this general decline in consumption in 2001 was 1.0 Mt. Declines in consumption unit consumption of the ferroalloy form, and ferroalloy metal took place in the bulk ferroalloys manganese (including silico- from all sources, for the major ferroalloys in steelmaking. -

The Construction, Operation, and Dissolution of the Adirondack Iron and Steel Company’S “New Furnace”

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 45 Article 8 2016 Last Gap: The onsC truction, Operation, and Dissolution of the Adirondack Iron and Steel Company’s “New Furnace” David P. Staley Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Staley, David P. (2016) "Last Gap: The onC struction, Operation, and Dissolution of the Adirondack Iron and Steel Company’s “New Furnace”," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 45 45, Article 8. Available at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol45/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Northeast Historical Archaeology/Vol. 45, 2016 171 Last Gasp: The Construction, Operation, and Dissolution of the Adirondack Iron and Steel Company’s “New Furnace” David P. Staley Isolation and historical circumstances have largely preserved the “New Furnace” at the Adirondack Iron & Steel Company’s Upper Works. An historical account suggested that the operational process at the facility would be clearly represented by an array of tools and debris. Daily activities at a blast furnace tend to obliterate much of the archaeologically observable behavioral evidence, and decades of visitors and vandalism have removed any tools abandoned after the last casting. Through the interpretation of sediments, stratigraphy, features, and under-utilized material culture, such as building materials, smelting raw materials, and slag, it is possible to reveal aspects of construction, operations, collapse, and decay at the site.