Criminal Justice: Arrest for Seizure-Related Behaviors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

Non-Epileptic Seizures a Short Guide for Patients and Families

Non-epileptic seizures a short guide for patients and families Department of Neurology Information for patients Royal Hallamshire Hospital What are non-epileptic seizures? In a seizure people lose control of their body, often causing shaking or other movements of arms and legs, blacking out, or both. Seizures can happen for different reasons. During epileptic seizures, the brain produces electrical impulses, which stop it from working normally. Non-epileptic seizures look a little like epileptic seizures, but are not caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Non-epileptic seizures happen because of problems with handling thoughts, memories, emotions or sensations in the brain. Such problems are sometimes related to stress. However, they can also occur in people who seem calm and relaxed. Often people do not understand why they have developed non-epileptic seizures. Are non-epileptic seizures rare? For every 100,000 people, between 15 and 30 have non- epileptic seizures. Nearly half of all people brought in to hospital with suspected serious epilepsy turn out to have non- epileptic seizures instead. One of the reasons why you may not have heard of non- epileptic seizures is that there are several other names for the same problem. Non-epileptic seizures are also known as pseudoseizures, psychogenic, dissociative or functional seizures. Sometimes people who have non-epileptic seizures are told that they suffer from non-epileptic attack disorder (NEAD). How can I be sure that this is the right diagnosis? Non-epileptic seizures often look like epileptic seizures to friends, family members and even doctors. Like epilepsy, non- epileptic seizures can cause injuries and loss of control over bladder function. -

EPILEPSY and OTHER SEIZURE DISORDERS 273 Base of Rh

45077 Ropper: Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology, 8/E McGraw-Hill BATCH RIGHT top of rh CHAPTER 16 base of rh EPILEPSY AND OTHER cap height base of text SEIZURE DISORDERS In contemporary society, the frequency and importance of epilepsy logic disease that demands the employment of special diagnostic can hardly be overstated. From the epidemiologic studies of Hauser and therapeutic measures, as in the case of a brain tumor. and colleagues, one may extrapolate an incidence of approximately A more common and less grave circumstance is for a seizure 2 million individuals in the United States who are subject to epi- to be but one in an extensive series recurring over a long period of lepsy (i.e., chronically recurrent cerebral cortical seizures) and pre- time, with most of the attacks being more or less similar in type. dict about 44 new cases per 100,000 population occur each year. In this instance they may be the result of a burned-out lesion that These figures are exclusive of patients in whom convulsions com- originated in the past and remains as a scar. The original disease plicate febrile and other intercurrent illnesses or injuries. It has also may have passed unnoticed, or perhaps had occurred in utero, at been estimated that slightly less than 1 percent of persons in the birth, or in infancy, in parts of the brain inaccessible for exami- United States will have epilepsy by the age of 20 years (Hauser nation or too immature to manifest signs. It may have affected a and Annegers). -

Epilepsy Foundation Awards $300K in Grants for New Treatments

Epilepsy Foundation Awards $300K in Grants for New Treatments dravetsyndromenews.com/2019/02/05/epilepsy-foundation-awards-300k-in-grants-for-new- treatments/ Mary Chapman February 5, 2019 With the goal of advancing development of new treatments for patients living with poorly controlled seizures, the Epilepsy Foundation has awarded $300,000 in grants to two leading researchers. The grants will go to Matthew Gentry, PhD, a professor at the University of Kentucky, and Greg Worrell, MD, PhD, professor of neurology and chair of clinical neurophysiology at the Mayo Clinic, through the foundation’s New Therapy Commercialization Grants Program and Epilepsy Innovation Seal of Excellence Award. Each recipient will receive matching funding from commercial partners. Gentry was awarded $150,000 to support pre-clinical testing of a compound (VAL-1221) that has promise to treat Lafora disease, a progressive epilepsy caused by genetic abnormalities in the brain’s ability to process a sugar molecule called glycogen. Gentry has joined with Valerion Therapeutics to develop VAL-1221, now in clinical trials for Pompe disease, a rare genetic disorder characterized by the abnormal buildup of glycogen inside cells. Early evidence suggests the compound can break down aberrant glycogen in cells of Lafora patients. 1/3 Worrell will receive $150,000 to support research Cadence Neuroscience, an early-stage company developing medical device therapies for epilepsy treatment and management. The company’s core technology is management of uncontrolled epilepsy when a patient is undergoing Phase 2 evaluation for surgery. Early evidence suggests that this procedure, which tests a variety of electrical stimulation parameters on intractable (hard-to-manage) epilepsy patients during evaluation, can be used to customize brain therapy and enhance seizure control. -

An Atypical Presentation of Epilepsy; What a Headache! J Neurol Transl Neurosci 5(1): 1078

Central Journal of Neurology & Translational Neuroscience Bringing Excellence in Open Access Case Report Corresponding author Sarah Seyffert, Trinity School of Medicine, 505 Tadmore court Schaumburg, Illinois 60194, USA, Tel: 847-217-4262; An Atypical Presentation of Email: Submitted: 13 April 2017 Epilepsy; What a Headache! Accepted: 07 June 2017 Published: 09 June 2017 Sarah Seyffert* and Wade Kvatum ISSN: 2333-7087 Trinity School of Medicine, USA Copyright © 2017 Seyffert et al. Abstract OPEN ACCESS The relationship between headache and seizure is a poorly understood and controversial topic; however, the literature has recently suggested that the two conditions may be related. Keywords The interplay between these conditions seems to be even more complex in a group of • Epilepsy patients with epilepsy related headaches. It has been proposed that the association could • Headache be classified into preictal, ictal, postictal, or interictal headaches. Here we present a case • Ictal epileptic headache report of a 62 year old male who presented with a chief complaint of new onset severe headache and subsequently underwent multiple diagnostic testing modalities before he was finally diagnosed and treated for epilepsy, which lead to the resolution of his headache. We conclude with a short discussion of how to subcategorize seizure related headaches based on their temporal relationship and why they can pose such a difficult diagnostic challenge. ABBREVIATIONS afebrile with a normal CBC and CMP. On arrival to the hospital he underwent a non-contrast head CT scan; however, no evidence of EEG: Electroencephalogram; CBC: Complete Blood Count; acute intracranial abnormality was seen. Additionally, a lumbar CMP: Complete Metabolic Panel; CT scan: Computerized puncture was performed which was negative for xanthochromia Tomography Scan; CTA: Computed Tomographic Angiography; and showed a protein count of 27, glucose 230, and 2 white MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging blood cells. -

REN Newsletter Nov 2019

REN November 2019 RARE EPILEPSY NETWORK (REN) NEWSLETTER November 2019 Issue Aaron’s Ohtahara International Rett Foundation Syndrome Foundation Aicardi Syndrome Foundation The Jack Pribaz Foundation Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood KCNQ2 Cure Foundation Alliance Aspire for a Cure Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome Bridge the Gap Foundation SYNGAP Liv4TheCure The Brain Recovery Project NORSE Institute Carson Harris PCDH19 Alliance Foundation Inside this Issue: Phelan-McDermid CFC International Syndrome Foundation Chelsea’s Hope Pitt-Hopkins I. Upcoming events & News………..….….. p 2-6 The Cute Syndrome Research Foundation Foundation II. Active clinical trials and studies.….……. p 7 CSWS & ESES RASopathies Foundation Network III. About REN / Contact us ..….…………..… p 8 Doose Syndrome Ring 14 USA Epilepsy Alliance Outreach Dravet Syndrome Ring 20 Foundation Chromosome Alliance Dup15q Alliance SLC6A1 Connect Hope for Hypothalamic Hamartomas TESS Foundation Infantile Spasms Tuberous Sclerosis Community Alliance International Wishes for Elliott Foundation for CDKL5 Research !1 REN November 2019 SAVE THE DATES - KIm Rice The 4th International Lafora Workshop was held in San Diego September 6 – 8, 2018, attended by nearly 100 scientists and clinicians from eight countries as well as 25 family members of Lafora patients. Lafora research has progressed rapidly since the first Lafora Workshop in June, 2014, organized and funded by Chelsea’s Hope Lafora Research Fund. As a result of bringing together a handful of researchers working on REN workshop at the American this extremely rare orphan disease, the Lafora Epilepsy Epilepsy Society Meeting (AES) Cure Initiative (LECI) was formed and researchers are Sunday, December 8, 2019 now working collaboratively under a $9 million NIH grant. 12-2pm There are now two drug development companies (Ionis Hilton Baltimore, Baltimore, MD Pharmaceuticals and Valerion Therapeutics) More details to come soon. -

Seizure Triggers

SEIZURE TRIGGERS M A R I A R AQUEL LOPEZ. M.D M I A M I V H A DEFINITION OF SEIZURE VS. EPILEPSY • Epileptic seizure: Is a transient symptom of abnormal excessive electric activity of the brain. EPILEPSY • More than one epileptic seizure. TYPE OF SEIZURES ETIOLOGY • Epilepsy is a heterogeneous condition with varying etiologies including: 1. Genetic 2. Infectious 3. Trauma 4. Vascular 5. Neoplasm 6. Toxic exposures TRIGGERS FOR EPILEPTIC SEIZURES • What is a seizure trigger? It is a factor that can cause a seizure in a person who either has epilepsy or does not. • Factors that lead into a seizure are complex and it is not possible to determine the trigger in each patient. TRIGGERS A. Most common ones Stress Missing taking the medication THE MOST OFTEN REPORTED BY PATIENTS • Sleep deprivation and tiredness • Fever OTHER COMMON CAUSES . Infection . Fasting leading into hypoglycemia. Caffeine: particularly if it interrupts normal sleep patterns. Other medications like hormonal replacement, pain killers or antibiotics. OTHER TRIGGERS External precipitants • Alcohol consumption or withdrawal. *Specific triggers that are related to Reflex epilepsy Bathing Eating Reading OTHER TRIGGERS • Flashing light: especially with patients with idiopathic generalized seizure disorder STRESS . Stress is the most common patient –perceived seizure precipitant, studies of life events suggest that stressful experiences trigger seizures in certain individuals. Animals epilepsy models provide more convincing evidence that exposure to exogenous and endogenous stress mediators has been found to increase epileptic activity in the brain, especially after repeating exposure. SOLUTION ABOUT STRESS • Intervention of copying with stress STRESS MANAGEMENT • Include trying to get in a place of peace utilizing multiple techniques: • Regular exercise • Yoga and medication • Therapy or psychological support with a provider. -

Model Section 504 Plan for a Student with Epilepsy

8301 Professional Place, Landover, MD 20785 MODEL SECTION 504 PLAN FOR A STUDENT WITH EPILEPSY [NOTE: This Model Section 504 Plan lists a broad range of services and accommodations that might be needed by a student with epilepsy in the school setting and on school-related trips. The plan must be individualized to meet the specific needs of the particular child for whom the plan is being developed and should include only those items that are relevant to the child. Some students may need additional services and accommodations that have not been included in this Model Plan, and those services and accommodations should be included by those who develop the plan. The plan should be a comprehensive and complete document that includes all of the services and accommodations needed by the student.] Section 504 Plan for _____________________________ (Name of Student) Student I.D. Number__________________ School___________________________________ School Year_______________ _________________ ________________ Epilepsy____ Birth Date Grade Disability Homeroom Teacher_____________________ Bus Number________ OBJECTIVES/GOALS OF THIS PLAN: Epilepsy, also referred to as a seizure disorder, is generally defined by a tendency for recurrent seizures, unprovoked by any known cause such as hypoglycemia. A seizure is an event in the brain which is characterized by excessive electrical discharges. Seizures may cause a myriad of clinical changes. A few of the possibilities may include unusual mental disturbances such as hallucinations, abnormal movements, such as rhythmic jerking of limbs or the body, or loss of consciousness. In addition to abnormalities during the seizure itself, individuals may have abnormal mental experiences immediately before or after the seizure, or even in between seizures. -

Infantile Spasms Sign up for Our Quarterly Newsletter

PATIENTS OR CAREGIVERS ADVOCATES PROVIDERS OR RESEARCHERS DONORS Home Sign Up for Newsletter Who We Are What We Do Contact Donate Now Disorder Directory: Learn from the Experts EDUCATIONAL ARTICLES PLUS FAMILY STORIES AND RESOURCES INDEX A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Infantile Spasms Sign Up for Our Quarterly Newsletter ARTICLE FAMILY STORIES RESOURCES Get “Families First” plus updates on grants, family resources and more. Sign Up Now DON SHIELDS, MD Dr. Shields is Professor Emeritus of Neurology and Pediatrics, David Geffen Find Us On School of Medicine at UCLA Positions held in National and International and other medical organizations President, Child Neurology Foundation Recent Tweets Vice President, Pediatric Epilepsy Foundation Councilor, Child Neurology Society, 1994-1996 2/25/16 - Great read! @disabilityscoop In Bid To Nominating Committee, American Epilepsy Society, 1996 Understand Autism, Scientists Turn Membership Committee, Professors of Child Neurology, 1995 To Monkeys https://t.co/5t9uz6NhWu Chairman, Membership committee, Child Neurology Society, 1988-1993 https://t.co/5t9uz6NhWu Membership committee, Child Neurology Society, 1986-1988 Co-chairman Awards Committee, American Epilepsy Society, 1989-1992 2/25/16 - Informative read! @mnt Epilepsy and marijuana: could Awards for scientific accomplishment cannabidiol reduce seizures? https://t.co/E3TlMqTQpy UCLA School of Medicine Sherman Mellinkoff Faculty Award for dedication https://t.co/E3TlMqTQpy to the art of medicine and to the finest in doctor-patient -

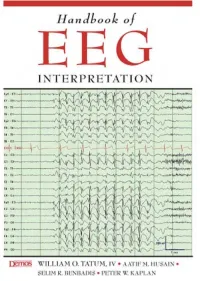

Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION This Page Intentionally Left Blank Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION

Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION This page intentionally left blank Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION William O. Tatum, IV, DO Section Chief, Department of Neurology, Tampa General Hospital Clinical Professor, Department of Neurology, University of South Florida Tampa, Florida Aatif M. Husain, MD Associate Professor, Department of Medicine (Neurology), Duke University Medical Center Director, Neurodiagnostic Center, Veterans Affairs Medical Center Durham, North Carolina Selim R. Benbadis, MD Director, Comprehensive Epilepsy Program, Tampa General Hospital Professor, Departments of Neurology and Neurosurgery, University of South Florida Tampa, Florida Peter W. Kaplan, MB, FRCP Director, Epilepsy and EEG, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center Professor, Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Baltimore, Maryland Acquisitions Editor: R. Craig Percy Developmental Editor: Richard Johnson Cover Designer: Steve Pisano Indexer: Joann Woy Compositor: Patricia Wallenburg Printer: Victor Graphics Visit our website at www.demosmedpub.com © 2008 Demos Medical Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved. This book is pro- tected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of EEG interpretation / William O. Tatum IV ... [et al.]. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-933864-11-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-933864-11-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Electroencephalography—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Tatum, William O. [DNLM: 1. Electroencephalography—methods—Handbooks. WL 39 H23657 2007] RC386.6.E43H36 2007 616.8'047547—dc22 2007022376 Medicine is an ever-changing science undergoing continual development. -

February 2021

¸ “Change is the law of life. And those who only look to the past or present are certain to miss the future,” -John F. Kennedy Foundation Quarterly Issue 1, February 2021 Welcome to the inaugural issue of Foundation The revamped Foundation Quarterly Quarterly, the Epilepsy Foundation’s features key initiatives that have had an quarterly e-magazine. impact on the epilepsy community and directly align with the five pillars of our While the 2020 global public health crisis 2025 Strategic Plan: brought many economic challenges for the Foundation, it also shed light on the way • Lead the conversation about epilepsy. we currently deliver services to people living with epilepsy and how these efforts • Shape the future of epilepsy healthcare measure up against the impact of our and research. mission. Last year, the Epilepsy Foundation underwent a significant transformation, • Harness the power of our united and though our structure and strategies network to improve lives. changed, our dedication to serving our community through advocacy, education, • Expand revenue sources beyond direct services, and research endures. traditional fundraising. We discovered new ways to meet the • Become a best-in-class organization challenges we faced with increased focus, leveraging technology and digital stronger partnerships, greater scale and assets for greater efficiency and efficiency, as well as new ways to connect mission delivery. with our community in a virtual world. We leveraged our digital engine to get the In this inaugural issue, you will read right resources to those living with epilepsy about the successful launch of our first- despite the barriers brought on by the ever Seizure Recognition & First Aid pandemic. -

Epilepsy and Psychosis

Central Journal of Neurological Disorders & Stroke Review Article Special Issue on Epilepsy and Psychosis Epilepsy and Seizures *Corresponding author Daniel S Weisholtz* and Barbara A Dworetzky Destînâ Yalcin A, Department of Neurology, Ümraniye Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard University, Boston Research and Training Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey, Massachusetts, USA Email: Submitted: 11 March 2014 Abstract Accepted: 08 April 2014 Psychosis is a significant comorbidity for a subset of patients with epilepsy, and Published: 14 April 2014 may appear in various contexts. Psychosis may be chronic or episodic. Chronic Interictal Copyright Psychosis (CIP) occurs in 2-10% of patients with epilepsy. CIP has been associated © 2014 Yalcin et al. most strongly with temporal lobe epilepsy. Episodic psychoses in epilepsy may be classified by their temporal relationship to seizures. Ictal psychosis refers to psychosis OPEN ACCESS that occurs as a symptom of seizure activity, and can be seen in some cases of non- convulsive status epilepticus. The nature of the psychotic symptoms generally depends Keywords on the localization of the seizure activity. Postictal Psychosis (PIP) may occur after • Epilepsy a cluster of complex partial or generalized seizures, and typically appears after • Psychosis a lucid interval of up to 72 hours following the immediate postictal state. Interictal • Hallucinations psychotic episodes (in which there is no definite temporal relationship with seizures) • Non-convulsive status epilepticus may be precipitated by the use of certain anticonvulsant drugs, particularly vigabatrin, • Forced normalization zonisamide, topiramate, and levetiracetam, and is linked in some cases to “forced normalization” of the EEG or cessation of seizures, a phenomenon known as alternate psychosis.