Ethnic Groups in Zagreb's Gradec in the Late Middle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-17549-4 - The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome J. Bert Lott Table of Contents More information CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables page ix Abbreviations xi Acknowledgments xiii 1 Introducing Neighborhoods at Rome and Elsewhere 1 Neighborhoods at Rome 4 Defining Neighborhoods 12 Defining Vici in Ancient Rome 13 Neighborhoods in Modern Thought 18 Voluntary Associations 24 Conclusion 25 2 Neighborhoods in the Roman Republic 28 Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Neighborhood Religion 30 The Middle Republic 37 The Late Republic 45 Social Disaffection, Populares, and Community Action 45 Magistri Vici and Collegia Compitalicia 51 Neighborhoods in the Final Years of the Republic 55 Conclusion 59 3 Republic to Empire 61 Julius Caesar 61 The Triumvirate 65 The Augustan Principate Before 7 b.c.e. 67 A Statue for Mercurius on the Esquiline 73 vii © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-17549-4 - The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome J. Bert Lott Table of Contents More information CONTENTS 4 The Reforms of Augustus 81 The Mechanics of Reform 84 The Ideology of Reform 98 Neighborhood Religion 106 Emperor and Neighborhood 117 Conclusion 126 5 The Artifacts of Neighborhood Culture 128 Think Globally, Act Locally 130 Altars in the Neighborhoods 136 Altar from the Vicus Statae Matris 137 Vatican Inventory 311 14 0 Altar of the Vicus Aesculeti 142 Altar of the Vicus Sandaliarius 144 Ara Augusta of Lucretius Zethus 146 Two Augustan Neighborhoods 148 Vicus Compiti Acili 148 Vicus of the Fasti Magistrorum Vici 152 Numerius Lucius Hermeros 161 Some Other Dedications and Magistri 165 Conclusion 168 6 Conclusion 172 Conclusion 175 Appendix. -

The Uncrowned Lion: Rank, Status, and Identity of The

Robert Kurelić THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ External Examiner Budapest May 2005 I, the undersigned, Robert Kurelić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. I also declare that no part of the thesis has been submitted in this form to any other institution of higher education for an academic degree. Budapest, 27 May 2005 __________________________ Signature TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ____________________________________________________1 ...heind graffen von Cilli und nyemermer... _______________________________ 1 ...dieser Hunadt Janusch aus dem landt Walachey pürtig und eines geringen rittermessigen geschlechts was.. -

Book of Abstracts Book of Abstracts

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS BOOK OF ABSTRACTS The 9th International Conference of the Faculty of Education and Rehabilitation Sciences University of Zagreb Zagreb, Croatia, 17 – 19 May, 2017 Faculty of Education and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Zagreb Faculty of Pedagogy, University of Ljubljana Department of Kinesiology, Recreation and Sports, Indiana State University ERFCON 2017 is organized under the auspices of the President of the Republic of Croatia, Mrs. Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović and the Mayor of Zagreb, Mr. Milan Bandić. PUBLISHER Faculty of Education and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Zagreb Scienific series, Book No. FOR PUBLISHER Snježana Sekušak-Galešev EDITORS Gordana Hržica Ivana Jeđud Borić GRAPHIC DESIGN Anamarija Ivanagić ISBN: The Publisher and the Editors are not to be held responsible for any substantial or linguistic imperfections that might be found in the abstracts published in this book. PROGRAMME COMMITTEE: HEAD OF THE COMMITTEE Snježana Sekušak-Galešev, PhD, Associate Professor, Vice Dean for Science Faculty of Education and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Zagreb, Croatia MEMBERS Sandra Bradarić Jončić, PhD, Professor Faculty of Education and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Zagreb, Croatia Belle Gavriel Fied, PhD, Professor The Gershon Gordon Faculty of Social Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Israel Phyllis B. Gerstenfeld, PhD, Professor and Chair of Criminal Justice California State University, Stanislaus, USA David Foxcroft, PhD, Professor Department of Psychology Social Work and Public Health -

Oligarchs, King and Local Society: Medieval Slavonia

Antun Nekić OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University CEU eTD Collection Budapest May2015 OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest Month YYYY OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest Month YYYY OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Supervisor CEU eTD Collection Budapest Month YYYY I, the undersigned, Antun Nekić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies, declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. -

About the Counts of Cilli

ENGLISH 1 1 Old Castle Celje Tourist Information Centre 6 Defensive Trench and Drawbridge ABOUT THE COUNTS OF CILLI 2 Veronika Café 7 Tower above Pelikan’s Trail 3 Eastern Inner Ward 8 Gothic Palatium The Counts of Cilli dynasty dates back Sigismund of Luxembourg. As the oldest 4 Frederick’s Tower (panoramic point) 9 Romanesque Palatium to the Lords of Sanneck (Žovnek) from son of Count Hermann II of Cilli, Frederick 5 Central Courtyard with a Well 10 Viewing platform the Sanneck (Žovnek) Castle in the II of Cilli was the heir apparent. In the Lower Savinja Valley. After the Counts of history of the dynasty, he is known for his Heunburg died out, they inherited their tragic love story with Veronika of Desenice. estate including Old Castle Celje. Frederick, His politically ambitious father married 10 9 Lord of Sanneck, moved to Celje with him off to Elizabeth of Frankopan, with 7 his family and modernised and fortified whom Frederick was not happy. When his the castle to serve as a more comfortable wife was found murdered, he was finally 8 residence. Soon after, in 1341, he was free to marry his beloved but thus tainted 4 10 elevated to Count of Celje, which marks the the reputation of the whole dynasty. He beginning of the Counts of Cilli dynasty. was consequently punished by his father, 5 6 The present-day coat-of-arms of the city who had him imprisoned in a 23-metre of Celje – three golden stars on a blue high defence tower and had Veronika background – also dates back to that period. -

Hellozagreb5.Pdf

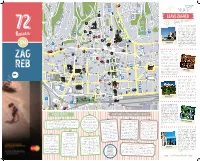

v ro e H s B o Šilobodov a u r a b a v h Put o h a r r t n e e o i k ć k v T T c e c a i a i c k Kozarčeve k Dvor. v v W W a a a Srebrnjak e l Stube l St. ć č Krležin Gvozd č i i s ć Gajdekova e k Vinogradska Ilirski e Vinkovićeva a v Č M j trg M l a a a Zamen. v č o e Kozarčeva ć k G stube o Zelengaj NovaVes m Vončinina v Zajčeva Weberova a Dubravkin Put r ić M e V v Mikloušić. Degen. Iv i B a Hercegovačka e k Istarska Zv k u ab on ov st. l on ar . ić iće Višnjica . e va v Šalata a Kuhačeva Franje Dursta Vladimira Nazora Kožarska Opatička Petrova ulica Novakova Demetrova Voćarska Višnjičke Ribnjak Voćarsko Domjanićeva stube naselje Voćarska Kaptol M. Slavenske Lobmay. Ivana Kukuljevića Zamenhoova Mletač. Radićeva T The closest and most charming Radnički Dol Posil. stube k v Kosirnikova a escape from Zagreb’s cityŠrapčeva noise e Jadranska stube Tuškanac l ć Tuškanac Opatovina č i i is Samobor - most joyful during v ć e e Bučarova Jurkovićeva J. Galjufa j j Markov v the famous Samobor Carnival i i BUS r r trg a Ivana Gorana Kovačića Visoka d d andJ. Gotovca widely known for the cream Bosanska Kamenita n n Buntićeva Matoševa A A Park cake called kremšnita. Maybe Jezuitski P Pantovčak Ribnjak Kamaufova you will have to wait in line to a trg v Streljačka Petrova ulica get it - many people arrive on l Vončinina i Jorgov. -

Sweet September

MARK YOUR MAPS WITH THE BEST OF MARKETS * Agram German exonym its Austrian by outside Croatia known commonly more was Zagreb LIMITED EDITION INSTAGRAM* FREE COPY Zagreb in full color No. 06 SEPTEMBER ast month, Zagreb was abruptly left without Dolac. 2015. LFor one week, stalls and vendors migrated to Ban Jelačić Square, only to move back to their original place, but now repaved, refurbished and in full color again. The Z ‘misplaced’ Dolac was a unique opportunity to be remind- on Facebook ed of what things were like half a century ago. This month 64-second kiss there is another time-travel experience on Jelačić Square: on the world’s Vintage Festival in the Johann Franck cafe, taking us shortest funic- back to the 50s and 60s. Read more about it in this issue... ular ride The world’s shortest funicular was steam-powered Talkabout until 1934. The lower stop on Croatia Tomićeva Street GRIČ-BIT IS BACK! connects with the upper stop on The fifth edition of the the Strossmayer best street festival kicks promenade, off on the first day of in front of the ANJA MUTIĆ fall, joining forces with Lotršćak Tower. Author of Lonely Planet Croatia, writes for New the ‘At the Upper Town’ As the Zagreb York Magazine and The Washington Post. Follow her at @everthenomad initiative and showcas- oldest means of public transport, ing Device_art work- the funicular shops and exhibitions began operating Sweet hosted by Space Festival only a year and the Klovićevi Dvori before the horse- gallery. All this topped drawn tram. -

Guide for Expatriates Zagreb

Guide for expatriates Zagreb Update: 25/05/2013 © EasyExpat.com Zagreb, Croatia Table of Contents About us 4 Finding Accommodation, 49 Flatsharing, Hostels Map 5 Rent house or flat 50 Region 5 Buy house or flat 53 City View 6 Hotels and Bed and Breakfast 57 Neighbourhood 7 At Work 58 Street View 8 Social Security 59 Overview 9 Work Usage 60 Geography 10 Pension plans 62 History 13 Benefits package 64 Politics 16 Tax system 65 Economy 18 Unemployment Benefits 66 Find a Job 20 Moving in 68 How to look for work 21 Mail, Post office 69 Volunteer abroad, Gap year 26 Gas, Electricity, Water 69 Summer, seasonal and short 28 term jobs Landline phone 71 Internship abroad 31 TV & Internet 73 Au Pair 32 Education 77 Departure 35 School system 78 Preparing for your move 36 International Schools 81 Customs and import 37 Courses for Adults and 83 Evening Class Passport, Visa & Permits 40 Language courses 84 International Removal 44 Companies Erasmus 85 Accommodation 48 Healthcare 89 2 - Guide for expats in Zagreb Zagreb, Croatia How to find a General 90 Practitioner, doctor, physician Medicines, Hospitals 91 International healthcare, 92 medical insurance Practical Life 94 Bank services 95 Shopping 96 Mobile Phone 99 Transport 100 Childcare, Babysitting 104 Entertainment 107 Pubs, Cafes and Restaurants 108 Cinema, Nightclubs 112 Theatre, Opera, Museum 114 Sport and Activities 116 Tourism and Sightseeing 118 Public Services 123 List of consulates 124 Emergency services 127 Return 129 Before going back 130 Credit & References 131 Guide for expats in Zagreb - 3 Zagreb, Croatia About us Easyexpat.com is edited by dotExpat Ltd, a Private Company. -

Zagreb Winter 2016/2017

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Zagreb Winter 2016/2017 Trešnjevka Where wild cherries once grew Go Gourmet A Croatian feast Shopping Cheat Sheet Find your unique item N°86 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Festive December Contents in Ljubljana ESSENTIAL CITY G UIDES Foreword 4 Sightseeing 46 A word of welcome Snap, camera, action Arrival & Getting Around 6 Zagreb Pulse 53 We unravel the A to Z of travel City people, city trends Zagreb Basics 12 Shopping 55 All the things you need to know about Zagreb Ready for a shopping spree Trešnjevka 13 Hotels 61 A city district with buzz The true meaning of “Do not disturb” Culture & Events 16 List of Small Features Let’s fill up that social calendar of yours Advent in Zagreb 24 Foodie’s Guide 34 Go Gourmet 26 Festive Lights Switch-on Event City Centre Shopping 59 Ćevap or tofu!? Both! 25. Nov. at 17:15 / Prešernov trg Winter’s Hot Shopping List 60 Restaurants 35 Maps & Index Festive Fair Breakfast, lunch or dinner? You pick... from 25. Nov. / Breg, Cankarjevo nabrežje, Prešernov in Kongresni trg Street Register 63 Coffee & Cakes 41 Transport Map 63 What a pleasure City Centre Map 64-65 St. Nicholas Procession City Map 66 5. Dec. at 17:00 / Krekov trg, Mestni trg, Prešernov trg Nightlife 43 Bop ‘till you drop Street Theatre 16. - 20. Dec. at 19:00 / Park Zvezda Traditional Christmas Concert 24. Dec. at 17:00 / in front of the Town Hall Grandpa Frost Proccesions 26. - 30. Dec. at 17:00 / Old Town New Year’s Eve Celebrations for Children 31. -

Report on Zagreb Museums

REPORT ZAGREB MUSEUMS SUFFER HEAVY DAMAGES IN THE RECENT EARTHQUAKE THAT HIT THE CITY DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC RESTRICTIONS When disasters strike, we are always reminded how emergency preparedness is a crucial procedure that every institution has to take care about. We are also reminded how vulnerable we are and how fragile our heritage is. Only a month ago the international conference on risk management held in Dubrovnik and organised by the Ministry of Culture within the Croatian EU presidency showed numerous threats, including those for museums, that have to be addressed by authorities and experts showed what should be done to reduce existing risks. However, when a real thing occurs, we can testify how poorly we are prepared. All the weaknesses became obvious and we can clearly see what the biggest challenges are and what a long-lasting neglect to invest in prevention can do. A strong 5.5 magnitude earthquake hit Zagreb at 6.24 on Sunday, March 22nd 2020. Luckily the streets of Croatia’s capital were empty and all institutions closed thus human casualties were avoided except a 15-year old girl who died from severe injuries caused by falling objects. Only a few seconds transformed the historic centre of Zagreb. Fallen facades and chimneys, damaged roofs, crashed vehicles that were parked on the streets were piling on a demolished property-lists. The town centre, which is home to many Croatian museums, was hit in the worst way. Buildings with poor construction could not resist the earthquake in spite that the magnitude was not the highest. -

HU 2010 Croatia

CROATIA Promoting social inclusion of children in a disadvantaged rural environment Antun Ilijaš and Gordana Petrović Centre for Social Care Zagreb Dora Dodig University of Zagreb Introduction Roma have lived in the territory of the Republic of Croatia since the 14th century. According to the 2001 population census, the Roma national minority makes up 0.21% of the population of Croatia, and includes 9463 members. However, according to the data of the Office for Ethnic Minority in Croatia, there is currently around 30 000 Roma people living in Croatia. It is difficult to accurately define the number of Roma people living in Croatia because some of them declare as members of some other nationality, and not as Roma. There is a higher density of Roma in some regions of Croatia: Medjimurje county, Osječko-baranjska county, Zagreb, Rijeka, Pula, Pitomača, Kutina, ðurñevac, Sisak, Slavonski Brod, Bjelovar, Karlovac and Vukovar. 1 Roma people in Croatia are considerably marginalised in almost all public and social activities and living conditions of Roma people are far more unsatisfactory than those of average population and other ethnic minorities. The position of Roma and their living conditions have been on the very margins of social interest for years, and this has contributed to the significant deterioration of the quality of their living conditions, as compared to the average quality of living conditions of the majority population. This regards their social status, the way in which their education, health care and social welfare are organised, the possibility to preserve their national identity, resolving of their status-related issues, employment, presentation in the media, political representation and similar issues. -

Medieval Biography Between the Individual and the Collective

Janez Mlinar / Medieval Biography Between the individual and the ColleCtive Janez Mlinar Medieval Biography between the Individual and the Collective In a brief overview of medieval historiography penned by Herbert Grundmann his- torical writings seeking to present individuals are divided into two literary genres. Us- ing a broad semantic term, Grundmann named the first group of texts vita, indicating only with an addition in the title that he had two types of texts in mind. Although he did not draw a clear line between the two, Grundmann placed legends intended for li- turgical use side by side with “profane” biographies (Grundmann, 1987, 29). A similar distinction can be observed with Vollmann, who distinguished between hagiographi- cal and non-hagiographical vitae (Vollmann, 19992, 1751–1752). Grundmann’s and Vollman’s loose divisions point to terminological fluidity, which stems from the medi- eval denomination of biographical texts. Vita, passio, legenda, historiae, translationes, miracula are merely a few terms signifying texts that are similar in terms of content. Historiography and literary history have sought to classify this vast body of texts ac- cording to type and systematize it, although this can be achieved merely to a certain extent. They thus draw upon literary-historical categories or designations that did not become fixed in modern languages until the 18th century (Berschin, 1986, 21–22).1 In terms of content, medieval biographical texts are very diverse. When narrat- ing a story, their authors use different elements of style and literary approaches. It is often impossible to draw a clear and distinct line between different literary genres.