Making Impressions the Adaptation of a Portuguese Family to Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The International Legal Personality of Macao' 24 Hong Kong Law Journal 328-341

ANALYSIS The International Legal Personality of Macau Introduction The question of international legal status/personality1 is increasingly difficult to answer with a degree of precision since the relevance of traditional criteria and symbols of statehood is diminishing in a global environment characterised by the proliferation of not-readily-definable entities which clamour for recog nition as autonomous political units.2 The requirements of 'a permanent population; a defined territory; govern ment; and capacity to enter into relations with other States'3 — which are accepted by international lawyers as 'customary international law' — by no means represent sufficient4 or even necessary3 qualifications of statehood. Clearly, the less legalistic symbols of statehood, such as kings/presidents, armies, central banks, currency, or passports, offer no reliable yardsticks.6 Nor for that matter is membership in the United Nations particularly instructive in respect of the key distinguishing attributes of statehood. Current members include Carribbean pinpoints such as Saint Christopher and Nevis or Saint Lucia, as well as other microentities like Vanuatu in the Pacific or San Marino in Europe — but not Taiwan.7 Neither is the UN practice with regards to admission — including the implementation of stipulated8 requirements 'International legal personality' is broadly defined in terms of the capacity to exercise international rights and duties. The International Standards Organisation, which assigns two-letter codes for country names, has 239 on -

Executive Summary Macau Became a Special Administrative Region

Executive Summary Macau became a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) on December 20, 1999. Macau's status, since reverting to Chinese sovereignty, is defined in the Sino-Portuguese Joint Declaration (1987) and the Basic Law, Macau's constitution. Under the concept of “One Country, Two Systems” articulated in these documents, Macau enjoys a high degree of autonomy in economic matters, and its economic system is to remain unchanged for fifty years. The Government of Macau (GOM) maintains a transparent, non-discriminatory, and free-market economy. The GOM is committed to maintaining an investor-friendly environment. In 2002, the GOM ended a long-standing gaming monopoly, awarding two gaming concessions to consortia with U.S. interests. This opening has encouraged substantial U.S. investment in casinos and hotels, and has spurred exceptionally rapid economic growth over the last few years. Macau is today the undisputed gaming capital of the world, having surpassed Las Vegas in terms of gambling revenue in 2006. U.S. investment over the past decade is estimated to exceed US$10 billion. In addition to gaming, Macau is positioning itself to be a regional center for incentive travel, conventions, and tourism. The American business community in Macau has continued to grow. In 2007, business leaders founded the American Chamber of Commerce of Macau. 1. Openness to, and Restrictions Upon, Foreign Investment Macau became a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) on December 20, 1999. Macau's status, since reverting to Chinese sovereignty, is defined in the Sino-Portuguese Joint Declaration (1987) and the Basic Law, Macau's constitution. -

Mediation Conference 2014 “Mediate First for a Win-Win Solution” Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre, Meeting Room N101 20 – 21 March 2014

Mediation Conference 2014 “Mediate First for a Win-Win Solution” Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre, Meeting Room N101 20 – 21 March 2014 Conference Programme Thursday, 20 March 2014 (Conducted in English) 8:30 - 9:00 Registration Welcome Addresses 9:00 - 9:30 The Honourable Chief Justice Geoffrey MA Tao-li, GBM Chief Justice, The Court of Final Appeal, Judiciary The Honourable Mr Rimsky YUEN, SC, JP Secretary for Justice, Government of HKSAR Chairperson of the Steering Committee on Mediation 9:30 - 10:00 Keynote Speech The Right Honourable The Lord Woolf of Barnes Former Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales 10:00 - 10:20 Question and Answer Session with Keynote Speaker The Right Honourable The Lord Woolf of Barnes Former Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales Moderator: Prof. Christopher TO Executive Director of Construction Industry Council, Council Member of Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre, Member of the Steering Committee on Mediation and the Accreditation Sub-committee 10:20 - 10:25 Première Broadcast of the 2nd Announcement in Public Interest “Mediate First for a Win-Win Solution” 10:25 - 10:45 Refreshment Break 10:45 - 12:15 Plenary Session: The Global Trend in Mediation Mediation is increasingly popular around the world as an effective alternative dispute resolution method in view of its advantages. A detailed review of the latest development of mediation in Australasia, United Kingdom, Europe, North America, China and the Asia Pacific Region. 1 Moderator: Mr. Danny McFadden Managing Director of CEDR Asia Pacific Speakers: The Honourable Madam Justice P A BERGIN Chief Judge in Equity, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Australia Dr. -

25% Bracara Tour

Sé de Braga Basílica dos Congregados Sameiro Braga Cathedral Congregados Basilica Sameiro A Sé de Braga assenta sobre as bases de um A Basílica dos Congregados é uma obra antigo templo romano dedicado a Ísis. Nesta incluída no antigo Convento dos Congregados e BRAGA catedral encontram-se os túmulos de Henrique de construída entre os séculos XVI e XX. As FREE CITY MAP Borgonha e sua mulher, Teresa de Leão, condes estátuas da fachada - São Filipe de Nery e São do Condado Portucalense, pais do rei D. Afonso Martinho de Dume - são obra do escultor Manuel Henriques, primeiro Rei de Portugal. da Silva Nogueira. Braga’s Cathedral was built over an ancient The Congregados Basilica makes part of the Roman temple dedicated to the Goddess Ísis. ancient Congregados Convent. It was built Inside its walls you can find the tombs of Henrique de Borgonha and his wife Teresa de between the 16th and 20th centuries. The Leão. These were Counts of the Portucalense statues on the facade – St. Filipe de Nery and County and parents of D. Afonso Henriques, the St. Martinho de Dume – were made by the Bracara Tour first King of Portugal. sculpturer Manuel da Silva Nogueira. Arco da Porta Nova Ruínas Romanas Arco da Porta Nova Roman Ruins O Arco da Porta Nova é um arco barroco e Braga é a mais antiga cidade portuguesa e O Santuário do Sameiro é um local de The Sanctuary of Sameiro is a devotional neoclássico que decora a entrada oeste da uma das cidades cristãs mais antigas do devoção à Virgem Maria localizado nos shrine to the Virgin Mary located in the muralha medieval da cidade. -

GLOBAL HISTORY and NEW POLYCENTRIC APPROACHES Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History

Foreword by Patrick O’Brien Edited by Manuel Perez Garcia · Lucio De Sousa GLOBAL HISTORY AND NEW POLYCENTRIC APPROACHES Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History Series Editors Manuel Perez Garcia Shanghai Jiao Tong University Shanghai, China Lucio De Sousa Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Tokyo, Japan This series proposes a new geography of Global History research using Asian and Western sources, welcoming quality research and engag- ing outstanding scholarship from China, Europe and the Americas. Promoting academic excellence and critical intellectual analysis, it offers a rich source of global history research in sub-continental areas of Europe, Asia (notably China, Japan and the Philippines) and the Americas and aims to help understand the divergences and convergences between East and West. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15711 Manuel Perez Garcia · Lucio De Sousa Editors Global History and New Polycentric Approaches Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Editors Manuel Perez Garcia Lucio De Sousa Shanghai Jiao Tong University Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Shanghai, China Fuchu, Tokyo, Japan Pablo de Olavide University Seville, Spain Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History ISBN 978-981-10-4052-8 ISBN 978-981-10-4053-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4053-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017937489 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018, corrected publication 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

SAP Crystal Reports

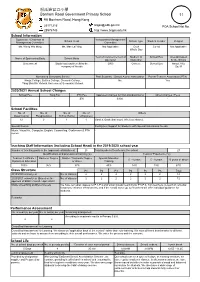

般咸道官立小學 Bonham Road Government Primary School 11 9A Bonham Road, Hong Kong 25171216 [email protected] POA School Net No. 28576743 http://www.brgps.edu.hk School Information Supervisor / Chairman of Incorporated Management School Head School Type Student Gender Religion Management Committee Committee Ms. Wong Wai Ming Ms. Man Lai Ying Not Applicable Gov't Co-ed Not Applicable Whole Day Year of Commencement of Medium of School Bus Area Occupied Name of Sponsoring Body School Motto Operation Instruction by the School Government Study hard and benefit by the 2000 Chinese School Bus About 3765 company of friends Sq. M Nominated Secondary School Past Students' / School Alumni Association Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) King's College, Belilios College, Clementi College, No Yes Tang Shiu Kin Victoria Government Secondary School 2020/2021 Annual School Charges School Fee Tong Fai PTA Fee Approved Charges for Non-standard Items Other Charges / Fees - - $70 $300 - School Facilities No. of No. of No. of No. of Others Classroom(s) Playground(s) School Hall(s) Library(ies) 12 2 1 1 Garden, Basketball court, Wireless intranet. Special Rooms Facility(ies) Support for Students with Special Educational Needs Music, Visual Art, Computer, English, Counselling, Conference & PTA - rooms. Teaching Staff Information (including School Head) in the 2019/2020 school year Number of teaching posts in the approved establishment 25 Total number of teachers in the school 27 Qualifications and professional training (%) Years of Experience (%) Teacher Certificate / Bachelor Degree Master / Doctorate Degree Special Education 0 - 4 years 5 - 9 years 10 years or above Diploma in Education or above Training 100% 96% 33% 40% 14% 19% 67% Class Structure P1 P2 P3 P4 P5 P6 Total 2019/2020 school year No. -

Sanctuary of Bom Jesus Do Monte in Braga an ICOMOS Technical Evaluation Mission Visited the Location Property on 17-20 September 2018

1 Basic data Sanctuary of Bom Jesus do Monte in Included in the Tentative List Braga 31 January 2017 (Portugal) Background No 1590 This is a new nomination. Consultations and Technical Evaluation Mission Desk reviews have been provided by ICOMOS International Scientific Committees, members and Official name as proposed by the State Party independent experts. Sanctuary of Bom Jesus do Monte in Braga An ICOMOS technical evaluation mission visited the Location property on 17-20 September 2018. Northern Region, Municipality of Braga Portugal Additional information received by ICOMOS A letter was sent to the State Party on 8 October 2018 Brief description requesting further information about the comparative The Sanctuary of Bom Jesus do Monte in Braga is a cultural analysis, integrity, authenticity, factors affecting the landscape located on the steep slopes of Mount Espinho property, management and protection. overlooking the city of Braga in the north of Portugal. It is a landscape and architectural ensemble constituting a sacred An Interim Report was provided to the State Party on mount symbolically recreating the landscape of Christian 21 December 2018 summarizing the issues identified by Jerusalem and portraying the elaborate narrative of the the ICOMOS World Heritage Panel. Passion of Christ (the period in the life of Jesus from his entry to Jerusalem through to His crucifixion). Developed Further information was requested in the Interim Report, over a period of more than 600 years, the ensemble is including: mapping of the property, augmenting the focused on a long and complex Via Crucis (Way of the comparative analysis, the status of exclusions of parts of Cross) which leads up the mount’s western slope. -

2016 2 Bollettinoeng LOW.Pdf

Growth Architectures Growth is a need that since forever has accompanied mankind and all the phenomena in which it appears. Growth shouldn’t just be acknowledged, but also understood, analyzed and… measured. But how? Measuring growth today has become an obsession that translates into numbers, which are objective and reassuring, but not always able to indicate the real value of a phenomenon. That’s the key issue: value. Growth is not just an inevitable part of human nature, but also a mechanism that can produce value. There are several phenomena in which the need for growth is evident: are we sure that they can all improve our lives? Let’s learn to measure their value ahead of their size. —ak. OPENING REMARKS OPENING REMARKS Growth Architectures The demand for growth is permanent and endless. But, looking towards the future, how much of that growth can be Without continual growth planned and is it possible to build “ growth in an efficient and sustainable and progress, such words as manner? Can individuals and their He who moves not improvement, achievement habitats thrive in an open-source, “ international and sustainable way? forward, goes backward” and success have no meaning” In just one week the world can change. by Simone Bemporad The previous issue of il bollettino ‘The —Goethe —Benjamin Franklin Editor in Chief Place to Be’ reviewed in detail the European Project and its effect on the lives of its citizens. Now, with Brexit in the one hand, the physical environment, into its cities. By 2026, it hopes to move dynamism of the Silicon Valley. -

The Effect of the Establishment of the Portuguese Republic on the Revenue of Secular Brotherhoods—The Case of “Bom Jesus De Braga”1

The Effect of the Establishment of the Portuguese Republic on the Revenue of Secular 1 Brotherhoods—the Case of “Bom Jesus de Braga” Paulo Mourão2 Abstract Following its establishment in 1910, the First Portuguese Republic adopted a markedly anticlerical profile during its early years. Consequently, we hypothesize that the revenue of Portuguese religious institutions should reflect a clear structural break in 1910. However, one of Portugal’s most important historical pilgrimage sites (“Bom Jesus de Braga”) does not seem to have experienced a very significant break. Relying on time series econometrics (consisting primarily of recurring tests for multiple structural breaks), we studied the series of the Bom Jesus revenue between 1863 and 1952 (i.e., between the confiscation of church property by the constitutional monarchy and the stabilization of the Second Republic). It was concluded that 1910 does not represent a significant date for identifying a structural break in this series. However, the last quarter of the nineteenth century cannot be neglected in terms of the structural changes occurring in the Bom Jesus revenue. Keywords Portuguese economic history; anticlericalism; Bom Jesus de Braga; structural breaks Resumo Após o estabelecimento, em 1910, a Primeira República Portuguesa assumiu um perfil anticlerical durante os seus primeiros anos. Consequentemente, poderíamos supor que as receitas das instituições religiosas portuguesas refletiram quebras estruturais em 1910. No entanto, um dos mais importantes centros históricos de peregrinação de Portugal (o "Bom Jesus de Braga") parece ter passado esses anos sem quebras significativas. Baseando-nos em análises econométricas de séries temporais (principalmente testes sobre quebras estruturais), estudámos com detalhe a série de receitas de Bom Jesus entre 1863 e 1952 (ou seja, entre o confisco da propriedade da igreja pela monarquia constitucional e a estabilização da Segunda República). -

Cultural Aspects of Sustainability Challenges of Island-Like Territories: Case Study of Macau, China

Ecocycles 2016 Scientific journal of the European Ecocycles Society Ecocycles 1(2): 35-45 (2016) ISSN 2416-2140 DOI: 10.19040/ecocycles.v1i2.37 ARTICLE Cultural aspects of sustainability challenges of island-like territories: case study of Macau, China Ivan Zadori Faculty of Culture, Education and Regional Development, University of Pécs E-mail: [email protected] Abstract - Sustainability challenges and reactions are not new in the history of human communities but there is a substantial difference between the earlier periods and the present situation: in the earlier periods of human history sustainability depended on the geographic situation and natural resources, today the economic performance and competitiveness are determinative instead of the earlier factors. Economic, social and environmental situations that seem unsustainable could be manageable well if a given land or territory finds that market niche where it could operate successfully, could generate new diversification paths and could create products and services that are interesting and marketable for the outside world. This article is focusing on the sustainability challenges of Macau, China. The case study shows how this special, island-like territory tries to find balance between the economic, social and environmental processes, the management of the present cultural supply and the way that Macau creates new cultural products and services that could be competitive factors in the next years. Keywords - Macau, sustainability, resources, economy, environment, competitiveness -

Romanesque Architecture and Arts

INDEX 9 PREFACES 17 1ST CHAPTER 19 Romanesque architecture and arts 24 Romanesque style and territory: the Douro and Tâmega basins 31 Devotions 33 The manorial nobility of Tâmega and Douro 36 Romanesque legacies in Tâmega and Douro 36 Chronologies 40 Religious architecture 54 Funerary elements 56 Civil architecture 57 Territory and landscape in the Tâmega and Douro between the 19th and the 21st centuries 57 The administrative evolution of the territory 61 Contemporary interventions (19th-21st centuries) 69 2ND CHAPTER 71 Bridge of Fundo de Rua, Aboadela, Amarante 83 Memorial of Alpendorada, Alpendorada e Matos, Marco de Canaveses ROMANESQUE ARCHITECTURE AND ARTS omanesque architecture was developed between the late 10th century and the first two decades of the 11th century. During this period, there is a striking dynamism in the defi- Rnition of original plans, new building solutions and in the first architectural sculpture ex- periments, especially in the regions of Burgundy, Poitou, Auvergne (France) and Catalonia (Spain). However, it is between 1060 and 1080 that Romanesque architecture consolidates its main techni- cal and formal innovations. According to Barral i Altet, the plans of the Romanesque churches, despite their diversity, are well defined around 1100; simultaneously, sculpture invades the building, covering the capitals and decorating façades and cloisters. The Romanesque has been regarded as the first European style. While it is certain that Romanesque architecture and arts are a common phenomenon to the European kingdoms of that period, the truth is that one of its main stylistic characteristics is exactly its regional diversity. It is from this standpoint that we should understand Portuguese Romanesque architecture, which developed in Portugal from the late 11th century on- wards.