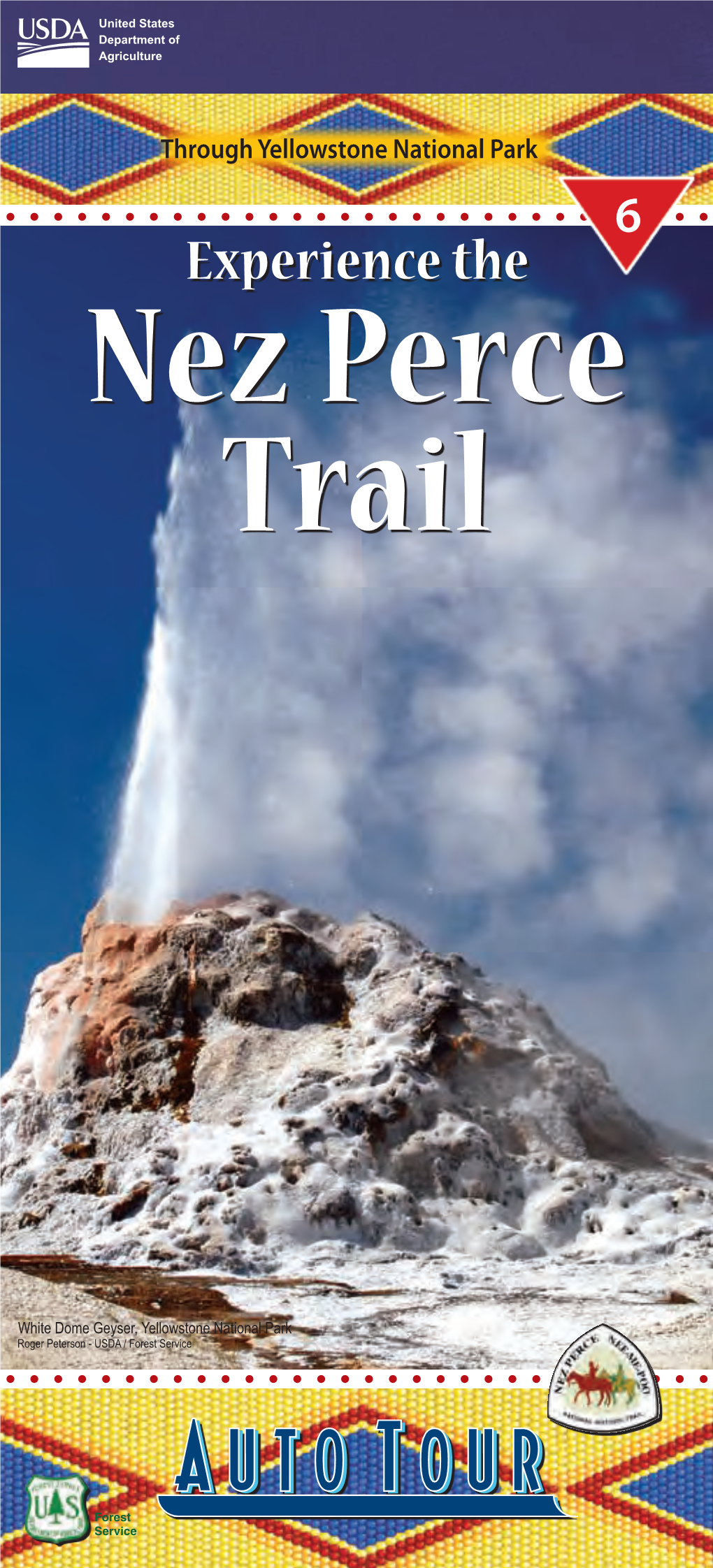

Experience the Nez Perce National Historic Trail Through Yellowstone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V- 447 in STORAGE PROGRESS REPORI' of COYOTE S'iuijy !Iifjyellowstone NATIONAL PARK

c 1 l < V- 447 IN STORAGE PROGRESS REPORI' OF COYOTE S'IUIJY !IifJYELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK by Adolph Murie ;r.3!3 I In a letter dated March 25, 1937, the Regional Officer, Region 2, was requested by the Director to assign me to make a thorough study of the coyote and its relationships to other wildlife species in Yellowstone National Park. In compliance with this request I reached Yellowstone May 1 to begin field studies of the coyote and other species on which it preys. Although it has not been possible to devote all of my time to this study I feel that it has not suffered greatly as a result of other special assignments given me and that fairly good continuity in observations has been ma intained. Special assign ments kept me away from Yellatqstone for various periods as follows:- Wind River Mountain investigation, July 26 - August l; i9'lathead .lforest investigation, August 8 - 22; Shoshone ..l!'orest trip, September 6 - 14. Most of October was spent in the Omaha. office and December was devoted to the analyslbs of scats in Jackson, Wyoming. This brief report on the coyote study is being ma.de at the request of Mr. Cahalane, Acting Chief of the • ildlife Division, in a letter dated December 20, to Mr. Allen, Region al Director, Region 2. A copy of this letter was sent to me at Yellowstone and mis-forwarded to 1ioran, fanilly reaching me today, January 5. Since the report is wanted in Washington by the middle of January there is not time for making anything but a brief report on my findings so far. -

A “Who's Who” of Bats

v o l u m e 1 5 • n u m b e r 3 • 2 0 0 7 A “Who’s Who” of Bats Lichens in Yellowstone National Park Who Are Yellowstone’s Backcountry Users? Yellowstone Denied NPS/HARLAN KREDIT A backcountry campsite (since removed) on the southeast arm of Yellowstone Lake, 1976. Celebrating the Less Noted HIS ISSUE OF YELLOWSTONE SCIENCE highlights a Lichens are partnerships of algae and fungi, and Sharon few less-noted park species, visitors, and historical per- Eversman shares results from various studies on these often Tsonalities. To enjoy such species, one needs to stay up overlooked organisms in her article. Besides being of interest a little later or get up a little earlier, and look a little closer. To for their symbiotic system and their many colors and shapes, understand the preferences of a small subset of park visitors, their presence is an indicator of environmental condition. one must seek them out and ask a lot of questions. And to Tim Oosterhous et al. surveyed those who choose a dif- appreciate one of these eccentrics from Yellowstone’s past, one ferent experience than most of the park’s three million annual needs to delve a little deeper into Yellowstone’s history. visitors—overnight backcountry recreationists. The results of Doug Keinath’s article on bats delights us with some this social science study will be of interest to park managers in incredible photos of these nocturnal animals. Until recently, defining a typical backcountry user and what kind of experi- no one really knew which species occurred in Yellowstone, but ences they are seeking. -

November 2020- January 2021

AMERICAN LEGION DEPARTMENT OF MONTANA Non-Profit Org. ARMED FORCES RESERVE CENTER U.S. Postage P.O. BOX 6075 HELENA, MT 59604-6075 PAID Permit No. 189 Helena, MT 59601 Volume 98, No. 2 November 2020— January 2021 RAYMOND J NYDEGGER Important Upcoming Dates Nov 11 ........................... Veterans Day DEPARTMENT COMMANDER 1975-76 Nov 26 ........................... Thanksgiving Raymond J Nydegger, Depart- Ray was very civic minded, he Dec 7 .......................Pearl Harbor Day ment Commander 1975-76 of belonged to the Masons, Eastern Dec 9 .....................75% Target Date – Renewal Cut Off Date Melstone, a 65-year member of Star and Shrine; he was also Dec 11 .................................Hanukkah Townsend Post 42 passed away on a former Dad Advisor for the Dec 15 .............. All Employer Awards August 18, 2020. Ray served in the DeMolay and a former Mayor of due to Department US Navy aboard the AE4 USS MT Townsend. Dec 25 ............................... Christmas Baker, an ammunition ship, during Dec 26 .........All 2021 Cash Calendars Ray is survived by his wife due back to Department the Korean War. Jeanne of Melstone, who served Jan 1 ................. New Year’s Day 2021 Ray held all elected offices of the as the Department Auxiliary Jan 2 ..........First 2021 Big K Drawings Post and District; additionally, he President the same year Ray was First 2021 Cash Calendar held many of the appointed offices drawings Commander; and his daughters, Jan 5 ...........................MT Legionnaire in both the Post and District. At Jennifer Bergin and Jody Haa- Feb / Mar / Apr issue cutoff date the Department level he served as gland; and son John. -

To See a Complete List of All Special Plates Types Available

2021 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATE FUND INFORMATION Plate Program Fund Name Responsible Organization (Idaho Code) Program Purpose Friends of 4-H Division University of Idaho Foundation 4H (49-420M) Funds to be used for educational events, training materials for youth and leaders, and to better prepare Idaho youth for future careers. Agriculture Ag in the Classroom Account Department of Agriculture (49-417B) Develop and present an ed. program for K-12 students with a better understanding of the crucial role of agriculture today, and how Idaho agriculture relates to the world. Appaloosa N/A Appaloosa Horse Club (49-420C) Funding of youth horse programs in Idaho. Idaho Aviation Foundation Idaho Aviation Association Aviation (49-420K) Funds use by the Idaho Aviation Foundation for grants relating to the maintenance, upgrade and development of airstrips and for improving access and promoting safety at backcountry and recreational airports in Idaho. N/A - Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation Biking (49-419E) Funds shall be used exclusively for the preservation, maintenance, and expansion of recreational trails within the state of Idaho and on which mountain biking is permitted. Capitol Commission Idaho Capitol Endowment Income Fund – IC 67-1611 Capitol Commission (49-420A) To help fund the restoration of the Idaho Capitol building located in Boise, Idaho. Centennial Highway Distribution Account Idaho Transportation Department (49-416) All revenue shall be deposited in the highway distribution account. Choose Life N/A Choose Life Idaho, Inc. (49-420R) To help support pregnancy help centers in Idaho. To engage in education and support of adoption as a positive choice for women, thus encouraging alternatives to abortion. -

History of Navigation on the Yellowstone River

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1950 History of navigation on the Yellowstone River John Gordon MacDonald The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation MacDonald, John Gordon, "History of navigation on the Yellowstone River" (1950). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2565. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2565 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY of NAVIGATION ON THE YELLOWoTGriE RIVER by John G, ^acUonald______ Ë.À., Jamestown College, 1937 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Mas ter of Arts. Montana State University 1950 Approved: Q cxajJL 0. Chaiinmaban of Board of Examiners auaue ocnool UMI Number: EP36086 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Ois8<irtatk>n PuUishing UMI EP36086 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Jackson Hole Vacation Planner Vacation Hole Jackson Guide’S Guide Guide’S Globe Addition Guide Guide’S Guide’S Guide Guide’S

TTypefypefaceace “Skirt” “Skirt” lightlight w weighteight GlobeGlobe Addition Addition Book Spine Book Spine Guide’s Guide’s Guide’s Guide Guide’s Guide Guide Guide Guide’sGuide’s GuideGuide™™ Jackson Hole Vacation Planner Jackson Hole Vacation2016 Planner EDITION 2016 EDITION Typeface “Skirt” light weight Globe Addition Book Spine Guide’s Guide’s Guide Guide Guide’s Guide™ Jackson Hole Vacation Planner 2016 EDITION Welcome! Jackson Hole was recognized as an outdoor paradise by the native Americans that first explored the area thousands of years before the first white mountain men stumbled upon the valley. These lucky first inhabitants were here to hunt, fish, trap and explore the rugged terrain and enjoy the abundance of natural resources. As the early white explorers trapped, hunted and mapped the region, it didn’t take long before word got out and tourism in Jackson Hole was born. Urbanites from the eastern cities made their way to this remote corner of northwest Wyoming to enjoy the impressive vistas and bounty of fish and game in the name of sport. These travelers needed guides to the area and the first trappers stepped in to fill the niche. Over time dude ranches were built to house and feed the guests in addition to roads, trails and passes through the mountains. With time newer outdoor pursuits were being realized including rafting, climbing and skiing. Today Jackson Hole is home to two of the world’s most famous national parks, world class skiing, hiking, fishing, climbing, horseback riding, snowmobiling and wildlife viewing all in a place that has been carefully protected allowing guests today to enjoy the abundance experienced by the earliest explorers. -

Soda Butte Creek

Soda Butte Creek monitoring and sampling schemes Final report for the Greater Yellowstone Network Vital Signs Monitoring Program Susan O’Ney Resource Management Biologist Grand Teton National Park P.O. Drawer 170 Moose, Wyoming 83012 Phone: (307) 739 – 3666 December 2004 SODA BUTTE CREEK and REESE CREEK: VITAL SIGNS MONITORING PROGRAM: FINAL REPORT December 2004 Meredith Knauf Department of Geography and Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research University of Colorado, Boulder Mark W. Williams* Department of Geography and Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research University of Colorado, Boulder *Corresponding Address Mark W. Williams INSTAAR and Dept. of Geography Campus Box 450 Boulder, Colorado 80309-0450 Telephone: (303) 492-8830 E-mail: [email protected] Soda_Butte_Creek_Compiled_with_Appendices .doc 5/17/2005 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY We have put together a final report on the recommendations for the Soda Butte Creek and Reese Creek Vital Signs Monitoring Program. The purpose of the grant was to develop detailed protocols necessary to monitor the ecological health of Soda Butte Creek and Reese Creek in and near Yellowstone National Park. The main objectives was to compile existing information on these creeks into one database, document the current conditions of Soda Butte and Reese Creeks by a one-time synoptic sampling event, and present recommendations for vital signs monitoring programs tailored to each creek’s needs. The database is composed of information from government projects by the United States Geological Survey and the United States Environmental Protection Agency, graduate student master’s theses, academic research, and private contractor reports. The information dates back to 1972 and includes surface water quality, groundwater quality, sediment contamination, vegetation diversity, and macroinvertebrate populations. -

Thomas Stuart Homestead Site: Historic Context Report

Thomas Stuart Homestead Historic Context Report Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Avana Andrade Public Lands History Center at Colorado State University 2/1/2012 1 Thomas Stuart Homestead Site: Historic Context Report Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site in Deer Lodge Montana is currently developing plans for a new contact station. One potential location will affect the site of a late-nineteenth-century historic homestead. Accordingly, the National Park Service and the Montana State Historic Preservation Office need more information about the historic importance of the Thomas Stuart homestead site to determine future decisions concerning the contact station. The following report provides the historic contexts within which to assess the resource’s historic significance according to National Register of Historic Places guidelines. The report examines the site’s association with Thomas Stuart, a Deer Lodge pioneer, and the Menards, a French- Canadian family, and presents the wider historical context of the fur trade, Deer Lodge’s mixed cultural milieu, and the community’s transformation into a settled, agrarian town. Though only indications of foundations and other site features remain at the homestead, the report seeks to give the most complete picture of the site’s history. Site Significance and Integrity The Thomas Stuart homestead site is evaluated according to the National Register of Historic Places, a program designed in the 1960s to provide a comprehensive listing of the United States’ significant historic properties. Listing on the National Register officially verifies a site’s importance and requires park administrators or land managers to consider the significance of the property when planning federally funded projects. -

10. Palouse Prairie Section

10. Palouse Prairie Section Section Description The Palouse Prairie Section, part of the Columbia Plateau Ecoregion, is located along the western border of northern Idaho, extending west into Washington (Fig. 10.1, Fig. 10.2). This section is characterized by dissected loess-covered basalt plains, undulating plateaus, and river breaks. Elevation ranges from 220 to 1,700 m (722 to 5,577 ft). Soils are generally deep, loamy to silty, and have formed in loess, alluvium, or glacial outwash. The lower reaches and confluence of the Snake and Clearwater rivers are major waterbodies. Climate is maritime influenced. Precipitation ranges from 25 to 76 cm (10 to 30 in) annually, falling primarily during the fall, winter, and spring, and winter precipitation falls mostly as snow. Summers are relatively dry. Average annual temperature ranges from 7 to 12 ºC (45 to 54 ºF). The growing season varies with elevation and lasts 100 to 170 days. Population centers within the Idaho portion of the section are Lewiston and Moscow, and small agricultural communities are dispersed throughout. Outdoor recreational opportunities include hunting, angling, hiking, biking, and wildlife viewing. The largest Idaho Palouse Prairie grassland remnant on Gormsen Butte, south of Department of Fish and Moscow, Idaho with cropland surrounding © 2008 Janice Hill Game (IDFG) Wildlife Management Area (WMA) in Idaho, Craig Mountain WMA, is partially located within this section. The deep and highly-productive soils of the Palouse Prairie have made dryland farming the primary land use in this section. Approximately 44% of the land is used for agriculture with most farming operations occurring on private land. -

Ultimate Western Swing Page 2 of 44 Trip Summary

Ultimate Western Swing Page 2 of 44 Trip Summary Day 1 Daily Overview Drive: Los Angeles, CA to Springdale, UT (450 Miles) Welcome to Springdale, Utah Day 2 Daily Overview Welcome to Zion National Park - Zion National Park ACTIVITY: Guided Half-Day Hike of The Narrows - The Narrows, Zion Narrows Tour Note: Confirm late check-out of RV Resort for tomorrow’s excursion (request 1:00 PM check-out time if possible). Day 3 Daily Overview Activity: Sandstone Slot Canyoneering Trip (guided) Drive: Springdale to Bryce Canyon Day 4 Daily Overview Acrivity: Explore Bryce Canyon Day 5 Daily Overview Drive: Bryce to Jackson, WY Welcome to Jackson Hole, Wyoming! - Jackson Hole Day 6 Daily Overview Getting around Jackson Hole and Grand Teton National Park - Jackson Hole Explore Grand Teton National Park - Teton National Forest Page 3 of 44 Day 7 Daily Overview Depart: Jackson to Cody Through Yellowstone (177 Miles) Welcome to Yellowstone National Park! - Yellowstone Park Service Stations, Service Stations Explore the Lewis River Canyon Area - Lewis Falls, Lewis Lake Explore West Thumb, Bridge Bay, Lake Yellowstone, and Hayden Valley Day 8 Daily Overview Welcome to Cody, Wyoming! Activity: Explore Cody Day 9 Daily Overview Drive: Cody to Sage Lodge - Through Cooke City (166 Miles) - Cooke City-Silver Gate, Albright Visitor Center, Sage Lodge Explore Lamar Valley and the Tower-Roosevelt Area. Explore the Mammoth Hot Springs Area. Welcome to Gardiner! - Gardiner Check in at Sage Lodge Day 10 Daily Overview Horseback riding and rafting in Paradise Valley -

Yellowstone National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Scoping

Geologic Resource Evaluation Scoping Summary Yellowstone National Park This document summarizes the results of a geologic resource evaluation scoping session that was held at Yellowstone National Park on May 16–17, 2005. The NPS Geologic Resources Division (GRD) organized this scoping session in order to view and discuss the park’s geologic resources, address the status of geologic maps and digitizing, and assess resource management issues and needs. In addition to GRD staff, participants included park staff and cooperators from the U.S. Geological Survey and Colorado State University (table 1). Table 1. Participants of Yellowstone’s GRE Scoping Session Name Affiliation Phone E-Mail Bob Volcanologist, USGS–Menlo Park 650-329-5201 [email protected] Christiansen Geologist/GRE Program GIS Lead, NPS Tim Connors 303-969-2093 [email protected] Geologic Resources Division Data Stewardship Coordinator, Greater Rob Daley 406-994-4124 [email protected] Yellowstone Network Supervisory Geologist, Yellowstone Hank Heasler 307-344-2441 [email protected] National Park Geologist, NPS Geologic Resources Bruce Heise 303-969-2017 [email protected] Division Cheryl Geologist, Yellowstone National Park 307-344-2208 [email protected] Jaworowski Katie Geologist/Senior Research Associate, 970-586-7243 [email protected] KellerLynn Colorado State University Branch Chief, NPS Geologic Resources Carol McCoy 303-969-2096 [email protected] Division Ken Pierce Surficial Geologist, USGS–Bozeman 406-994-5085 [email protected] Supervisory GIS Specialist, Yellowstone Anne Rodman 307-344-7381 [email protected] National Park Shannon GIS Specialist, Yellowstone National Park 307-344-7381 [email protected] Savage Monday, May 16, involved a welcome to Yellowstone National Park and an introduction to the Geologic Resource Evaluation (GRE) Program, including status of reports and digital maps. -

Recreational Trails Master Plan

Beaverhead County Recreational Trails Master Plan Prepared by: Beaverhead County Recreational Trails Master Plan Prepared for: Beaverhead County Beaverhead County Commissioners 2 South Pacific Dillon, MT 59725 Prepared by: WWC Engineering 1275 Maple Street, Suite F Helena, MT 59601 (406) 443-3962 Fax: (406) 449-0056 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 1 Overview ...................................................................................................................... 1 Public Involvement .................................................................................................... 1 Key Components of the Plan ..................................................................................... 1 Intent of the Plan ....................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 - Master Plan Overview................................................................................ 3 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 3 1.1.1 Project Location ............................................................................................... 3 1.2 Project Goals ......................................................................................................... 3 1.2.1 Variety of Uses ................................................................................................