10. Palouse Prairie Section

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

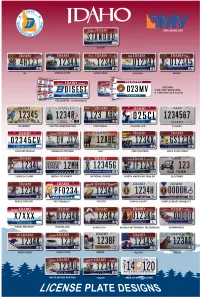

To See a Complete List of All Special Plates Types Available

2021 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATE FUND INFORMATION Plate Program Fund Name Responsible Organization (Idaho Code) Program Purpose Friends of 4-H Division University of Idaho Foundation 4H (49-420M) Funds to be used for educational events, training materials for youth and leaders, and to better prepare Idaho youth for future careers. Agriculture Ag in the Classroom Account Department of Agriculture (49-417B) Develop and present an ed. program for K-12 students with a better understanding of the crucial role of agriculture today, and how Idaho agriculture relates to the world. Appaloosa N/A Appaloosa Horse Club (49-420C) Funding of youth horse programs in Idaho. Idaho Aviation Foundation Idaho Aviation Association Aviation (49-420K) Funds use by the Idaho Aviation Foundation for grants relating to the maintenance, upgrade and development of airstrips and for improving access and promoting safety at backcountry and recreational airports in Idaho. N/A - Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation Biking (49-419E) Funds shall be used exclusively for the preservation, maintenance, and expansion of recreational trails within the state of Idaho and on which mountain biking is permitted. Capitol Commission Idaho Capitol Endowment Income Fund – IC 67-1611 Capitol Commission (49-420A) To help fund the restoration of the Idaho Capitol building located in Boise, Idaho. Centennial Highway Distribution Account Idaho Transportation Department (49-416) All revenue shall be deposited in the highway distribution account. Choose Life N/A Choose Life Idaho, Inc. (49-420R) To help support pregnancy help centers in Idaho. To engage in education and support of adoption as a positive choice for women, thus encouraging alternatives to abortion. -

U.S.: Legal War Rages Over 3-Foot-Long, Spitting Worm 16:35, January 30, 2008

U.S.: legal war rages over 3-foot-long, spitting worm 16:35, January 30, 2008 Described in 1897 by a taxonomist as "very abundant" a now rarely-found 3-foot-long worm that spits and smells like lilies is at the center of a legal dispute between conservationists and the U.S. government. When Frank Smith discovered the giant Palouse earthworm (Driloleirus americanus) in 1897, he described it as "very abundant." Nowadays, however, sightings of the worm are rare. The only recent confirmed worm sighting was made in 2005 by a University of Idaho researcher. Before that, the giant worm had not been spotted in 17 years, since 1988. It reportedly grows up to three feet long and has a peculiar flowery smell (Driloleirus is Latin for "lily-like worm"). The cream-colored or pinkish-white worm lived in permanent burrows as deep as 15 feet and spat at attackers. "This worm is the stuff that legends and fairy tales are made of. A pity we're losing it," said Steve Paulson, a board member of Friends of the Clearwater, a conservation group based in Moscow, Idaho. Unlike the European earthworms now common across the United States, the giant Palouse earthworm is native to the Americas. Specifically, the giant worm dwelled in the prairies of the Palouse, the area of the northwest United States. The Palouse has been dramatically altered by farming practices, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service noted. "The giant Palouse earthworm is extremely rare and faces substantial risk of extinction," said Noah Greenwald, a conservation biologist with the Center for Biological Diversity, a conservation group based in Tucson, Ariz. -

Natural Resources Research Institute, University of Minnesota Duluth

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp 2009 Project Abstract For the Period Ending December 30, 2012 PROJECT TITLE: Prevention and Early Detection of Asian Earthworms and Reducing the Spread of European Earthworms PROJECT MANAGER: Cindy Hale AFFILIATION: Natural Resources Research Institute, University of Minnesota Duluth MAILING ADDRESS: 5013 Miller Trunk Hwy CITY/STATE/ZIP: Duluth MN 55811 PHONE: 218/720-4364 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: [If applicable] FUNDING SOURCE: Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund LEGAL CITATION: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/staff/chale.asp APPROPRIATION AMOUNT: $150,000 Overall Project Outcome and Results We used a multi-pronged approach to quantify of the relative importance of different vectors of spread for invasive earthworms, make management and regulatory recommendations and create mechanisms for public engagement and dissemination of our project results through the Great Lakes Worm Watch website and diverse stakeholders. Internet sales of earthworms and earthworm related products posed large risks for the introduction of new earthworm species and continued spread of those already in the state. Of 38 earthworm products sampled, 87% were either contaminated with other earthworm species or provided inaccurate identification. Assessment of soil transported via ATV’s and logging equipment demonstrated that this is also a high risk vector for spread of earthworms across the landscape, suggesting that equipment hygiene, land management activities and policies should address this risk. Preliminary recommendations for organizations with regulatory oversight for invasive earthworms (i.e. -

The Giant Palouse Earthworm (Driloleirus Americanus)

PETITION TO LIST The Giant Palouse Earthworm (Driloleirus americanus) AS A THREATENED OR ENDANGERED SPECIES UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT June 30, 2009 Friends of the Clearwater Center for Biological Diversity Palouse Audubon Palouse Prairie Foundation Palouse Group of the Sierra Club 1 June 30, 2009 Ken Salazar, Secretary of the Interior Robyn Thorson, Regional Director U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1849 C Street N.W. Pacific Region Washington, DC 20240 911 NE 11th Ave Portland, Oregon Dear Secretary Salazar, Friends of the Clearwater, Center for Biological Diversity, Palouse Prairie Foundation, Palouse Audubon, Palouse Group of the Sierra Club and Steve Paulson formally petition to list the Giant Palouse Earthworm (Driloleirus americanus) as a threatened or endangered species pursuant to the Endangered Species Act (”ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1531 et seq. This petition is filed under 5 U.S.C. 553(e) and 50 CFR 424.14 (1990), which grant interested parties the right to petition for issuance of a rule from the Secretary of Interior. Petitioners also request that critical habitat be designated for the Giant Palouse Earthworm concurrent with the listing, pursuant to 50 CFR 424.12, and pursuant to the Administrative Procedures Act (5 U.S.C. 553). The Giant Palouse Earthworm (D. americanus) is found only in the Columbia River Drainages of eastern Washington and Northern Idaho. Only four positive collections of this species have been made within the last 110 years, despite the fact that the earthworm was historically considered “very abundant” (Smith 1897). The four collections include one between Moscow, Idaho and Pullman, Washington, one near Moscow Mountain, Idaho, one at a prairie remnant called Smoot Hill and a fourth specimen near Ellensberg, Washington (Fender and McKey- Fender, 1990, James 2000, Sánchez de León and Johnson-Maynard, 2008). -

Geologic Map of the Grangeville East Quadrangle, Idaho County, Idaho

IDAHO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIGITAL WEB MAP 86 MOSCOW-BOISE-POCATELLO SCHMIDT AND OTHERS Sixmile Creek pluton to the north near Orofino (Lee, 2004) and an age of indicate consistent dextral, southeast-side-up shear sense across this zone. REFERENCES GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE GRANGEVILLE EAST QUADRANGLE, IDAHO COUNTY, IDAHO CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS about 118 Ma in tonalite in the Hazard Creek complex to the south near Thus, the prebasalt history along this structure was likely oblique, dextral- McCall (Manduca and others, 1993). reverse shear that appears to offset the accreted terrane-continent suture Anderson, A.L., 1930, The geology and mineral resources of the region about zone by several miles in the adjoining Harpster quadrangle to the east. Orofino, Idaho: Idaho Geological Survey Pamphlet 34, 63 p. Quartz porphyry (Permian to Cretaceous)Quartz-phyric rock that is probably Artificial Alluvial Mass Movement Volcanic Rocks Intrusive Island-Arc Metavolcanic KPqp Barker, F., 1979, Trondhjemite: definition, environment, and hypotheses of origin, a shallow intrusive body. Highly altered and consists almost entirely of To the southeast of the Mt. Idaho shear zone, higher-grade, hornblende- Disclaimer: This Digital Web Map is an informal report and may be Deposits Deposits Deposits Rocks and Metasedimentary Rocks in Barker, F., ed., Trondhjemites, Dacites, and Related Rocks, Elsevier, New Keegan L. Schmidt, John D. Kauffman, David E. Stewart, quartz, sericite, and iron oxides. Historic mining activity at the Dewey Mine dominated gneiss and schist and minor marble (JPgs and JPm) occur along revised and formally published at a later time. Its content and format m York, p. -

Transcription of Comments

U.S. 95 Thorncreek Road to Moscow Project U.S. 95 Thorncreek Road to Moscow Comments Feb. 2006 – July 2007 Comment #1 Can you provide, for each alternative alignment: Number of miles of US95 that would be turned over to Latah County Number of miles that would be 5-lane non-divided o transcript of DVD voiceover (she must have been reading it from a text document) Thanks. Comment #2 I strongly urge you to abandon grandiose and expensive plans to relocate parts of the highway south of Moscow. Instead I favor the less expensive option of improving the existing highway by adding passing lanes and turn lanes where appropriate. Please consider this option. Thank you for your consideration. Comment #3 I am not in favor of plans to extend Highway 95 using the W-4 route. Thank you for noting this in your research of community desires. Comment #4 I'm a Moscow resident whose property borders the University of Idaho Arboretum. In recent months, our neighborhood has been involved in negotiations with the City of Moscow to avoid disrupting the beauty and tranquillity of the Arboretum by a Parks and Recreation Department proposal to build a seven-field ballpark across from the Arboretum on Palouse Drive. Those negotiations, involving a large parking lot, concession stand, water use, night lights, and a sound system, are ongoing. Regarding the proposed ballfields, the University administration has also voiced a desire to minimize the impact on the Arboretum. Adjacent neighborhoods have been united in seeking to protect the Arboretum as a one-of-a-kind asset to our community. -

Scientists Capture Elusive Giant Palouse Earthworm

April 27, 2010 Scientists Capture Elusive Giant Palouse Earthworm by Martin Kaste The giant Palouse earthworm, a big white worm native to the Palouse prairie region of Idaho and Washington state, was said to be abundant in the late 19th century — then seemed to disappear. Some people thought they never existed to begin with. But now, researchers are digging them up again — and that has some people worried. A Foot Long And Smells Like Lilies? Last month, Karl Umiker, a support scientist at the University of Idaho, was out on an unplowed fragment of prairie hunting the “big one” with a graduate student. There hadn’t been a confirmed sighting of the worm since 2005, but Umiker had a new tool at his disposal. He calls it an “electroshocker.” Jodi Johnson-Maynard, a soil ecologist at the University of Idaho in Moscow, has been leading the effort to collect samples of the giant After jolting the soil a couple of times, Umiker dug around, Palouse earthworm. and suddenly there it was. The worm was captured and is Photo: Martin Kaste, NPR now sitting in a freezer at the University of Kansas, where it was positively identified. But Umiker can’t say how big this prairie giant is. “The problem with earthworm stories is that they get longer and longer, and you can always stretch an earthworm,” he says. That’s “under the normal conditions — without stretching it — close to 20 centimeters.” That’s about 8 inches. Soil ecologist Jodi Johnson-Maynard, who heads the project, backpedals from the whole “giant” thing. -

Geologic Map of IDAHO

Geologic Map of IDAHO 2012 COMPILED BY Reed S. Lewis, Paul K. Link, Loudon R. Stanford, and Sean P. Long Geologic Map of Idaho Compiled by Reed S. Lewis, Paul K. Link, Loudon R. Stanford, and Sean P. Long Idaho Geological Survey Geologic Map 9 Third Floor, Morrill Hall 2012 University of Idaho Front cover photo: Oblique aerial Moscow, Idaho 83843-3014 view of Sand Butte, a maar crater, northeast of Richfield, Lincoln County. Photograph Ronald Greeley. Geologic Map Idaho Compiled by Reed S. Lewis, Paul K. Link, Loudon R. Stanford, and Sean P. Long 2012 INTRODUCTION The Geologic Map of Idaho brings together the ex- Map units from the various sources were condensed tensive mapping and associated research released since to 74 units statewide, and major faults were identified. the previous statewide compilation by Bond (1978). The Compilation was at 1:500,000 scale. R.S. Lewis com- geology is compiled from more than ninety map sources piled the northern and western parts of the state. P.K. (Figure 1). Mapping from the 1980s includes work from Link initially compiled the eastern and southeastern the U.S. Geological Survey Conterminous U.S. Mineral parts and was later assisted by S.P. Long. County geo- Appraisal Program (Worl and others, 1991; Fisher and logic maps were derived from this compilation for the others, 1992). Mapping from the 1990s includes work Digital Atlas of Idaho (Link and Lewis, 2002). Follow- by the U.S. Geological Survey during mineral assess- ments of the Payette and Salmon National forests (Ev- ing the county map project, the statewide compilation ans and Green, 2003; Lund, 2004). -

Idaho Scientists Find Fabled Worm 27 April 2010, by NICHOLAS K

Idaho scientists find fabled worm 27 April 2010, By NICHOLAS K. GERANIOS , Associated Press Writer Both worms had pink heads and bulbous tails, rounded unlike the flattened tails of nightcrawlers. The adult had a yellowish band behind the head. The university said the juvenile worm is being kept in the Moscow laboratory to provide DNA to help develop future identification techniques. The specimens were found by Shan Xu, an Idaho student, and Karl Umiker, a research support scientist. They also found three earthworm Image credit: Yaniria Sanchez-de Leon/University of cocoons, two of which have hatched and appear to Idaho also be giant Palouse earthworms. The discoveries followed the development of a new high-tech worm shocking probe that uses electricity (AP) -- Two living specimens of the fabled giant to push worms toward the surface. The probe was Palouse earthworm have been captured for the deployed starting last summer. first time in two decades, University of Idaho scientists revealed on Tuesday. Umiker discovered the worms while using the probe. After shooting more electricity through the Researchers on March 27 located an adult and a soil, the juvenile crawled to the surface. The adult juvenile specimen of the worms, which have remained just beneath the surface, and Umiker become near mythic creatures in the Palouse used a trowel to dig it out. region of Washington and Idaho. The adult specimen was positively identified by University of The Palouse earthworm was first reported to the Kansas earthworm expert Sam James a few scientific world in 1897. Few specimens were weeks later. -

Real Estate Service for North Central Idaho

EXPERIENCE North Central Visitor’s Guide | 2016 | 2017 2 EXPERIENCE NORTH CENTRAL IDAHO 4 Idaho County 10 Osprey: Birds of Prey 12 Clearwater County 16 US Highway 12 Waterfalls 22 Lewis County From the deepest gorge in 28 Heart of the Monster: History of the Nimiipuu North America to the prairies of harvest 34 Nez Perce County (and everything else in between). 39 The Levee Come explore with us. SARAH S. KLEMENT, 42-44Dining Guide PUBLISHER Traveling On? Regional Chamber Directory DAVID P. RAUZI, 46 EDITOR CONTRIBUTED PHOTO: MICHELLE FORD COVER PHOTO BY ROBERT MILLAGE. Advertising Inquires Submit Stories SARAH KLEMENT, PUBLISHER DAVID RAUZI, EDITOR Publications of Eagle Media Northwest [email protected] [email protected] 900 W. Main, PO Box 690, Grangeville ID 83530 DEB JONES, PUBLISHER (MONEYSAVER) SARAH KLEMENT, PUBLISHER 208-746-0483, Lewiston; 208-983-1200, Grangeville [email protected] [email protected] EXPERIENCE NORTH CENTRAL IDAHO 3 PHOTO BY ROBERT MILLAGE 4 EXPERIENCE NORTH CENTRAL IDAHO PHOTO BY SARAH KLEMENT PHOTO BY DAVID RAUZI A scenic view of the Time Zone Bridge greets those entering or leaving the Idaho County town of Riggins (above) while McComas Meadows (top, right) is a site located in the mountains outside of Harpster. (Right, middle) Hells Canyon is a popular fishing spot and (bottom, right) the Sears Creek area is home to a variety of wildlife, including this flock of turkeys. Idaho County — said to be named for the Steamer Idaho that was launched June 9, 1860, on the Columbia River — spans the Idaho PHOTO BY MOUNTAIN RIVER OUTFITTERS panhandle and borders three states, but imposing geography sets this area apart from the rest of the United States. -

Idaho County

❧ A Guide to National Register of Historic Places in IDAHO COUNTY Idaho County hIstorIC PreservatIon CommIssIon ❧ 2012 ❧ Foreward his guide identifies Idaho County properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places. TIt is designed to stimulate your curiosity and encourage you to seek more information about these and other important places in Idaho’s history. Most of the properties are privately owned and are not open to the public. Please respect the occupant’s right to privacy when viewing these special and historic properties. Publication of this free guide is possible through a grant from the National Park Service administered by the Idaho State Historical Society (ISHS). Idaho County Historic Preservation Commission This guide was compiled by the Idaho County Historic Preservation Commission whose purpose is to preserve and enhance cultural and historic sites throughout Idaho County and to increase awareness of the value of historic preservation to citizens and local businesses. Commission members are volunteers appointed by the Idaho County Commissioners. Current commission members include Cindy Schacher, President; Jim May, Secretary; Pat Ringsmith, Treasurer; Penny Casey; Bruce Ringsmith; Jim Huntley; and Jamie Edmondson. Acknowledgements The Idaho County Historic Preservation Commission recognizes the assistance and support from the following people to complete this project: Ann Swanson (ISHS)—Photos and editorial assistance Suzi Pengilly (ISHS)—Editorial assistance Cindy Schacher—Photos and editorial assistance Mary -

E Is for Earthworm an A-Z Guide

E is for Earthworm An A-Z Guide This book is a product of a learning expedition on earthworms. Following an in-depth study of these amazing creatures, the students set out to write a book that would detail all of the things they learned. The book is in the form of collage. Students studied illustrators that use collage and took inspiration from these artists. They worked hard on their handwriting skills and revised their ABC letter to make it high quality. Words were transcribed from student to teacher. Please enjoy the hard work of 18 creative students. E is for Earthworm An A-Z Guide Written and Illustrated by Palouse Prairie School Kindergarten Class Quade Tucker Sasha Lillian Emma Emmit Henry Jamie Matthew Asher Noah Rowan Ian Meradydd Amberlee Zackary Lizzie Satori Text Copyright © 2010 Palouse Prairie School - Kindergarten Class Illustrations Copyright © 2010 Palouse Prairie School - Kindergarten Class Cover design by Satori Zimmerman Layout/design Julene Ewert The illustrations in this book were executed with collage and mixed media. The text was set in 18 point Gills Sans. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to: Palouse Prairie School 1500 Levick Street Moscow, ID 83843 Printed in the United States of America First Edition Palouse Prairie School E is for Earthworms An A-Z Guide Summary: An ABC book about earthworms.