Journal of the American Viola Society, Volume 37, Number 2, Spring 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021.5.17 Chamber Fest 2 R3

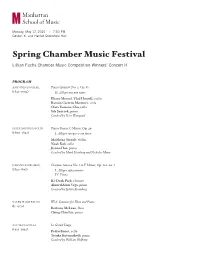

Monday, May 17, 2021 | 7:30 PM Gordon K. and Harriet Greenfield Hall Spring Chamber Music Festival Lillian Fuchs Chamber Music Competition Winners’ Concert II PROGRAM ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK Piano Quintet No. 2, Op. 81 (1841–1904) II. Allegro ma non tanto Eliane Menzel, Vlad Hontilă, violin Ramón Carrero Martínez, viola Clara Yeonsue Cho, cello Sıla Şentürk, piano Coached by Peter Winograd FELIX MENDELSSOHN Piano Trio in C Minor, Op. 49 <Piano Trio No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 66?> (1809–1847) I. Allegro energico e con fuoco Maïthéna Girault, violin Noah Koh, cello Jiyoon Han, piano Coached by Mark Steinberg and Nicholas Mann JOHANNES BRAHMS Clarinet Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120, no. 1 (1833–1897) I. Allegro appassionato IV. Vivace Ki-Deok Park, clarinet Ahmed Alom Vega, piano Coached by Sylvia Rosenberg VALERIE COLEMAN Wish: Sonatine for Flute and Piano (b. 1970) Bethany McLean, flute Ching Chia Lin, piano ASTOR PIAZOLLA Le Grand Tango (1921–1992) Pedro Bonet, cello Tatuka Kutsnashvili, piano Coached by William Wol!am Students in this performance are supported by the Robert Mann Endowed Scholarship for Violin and Chamber Studies, the Samuel and Mitzi Newhouse Scholarship, the Flavio Varani Scholarship in Piano, the Viola B. Marcus Memorial Scholarship, the Rachmael Weinstock Endowed Scholarship in Violin. We are grateful to the generous donors who made these scholarships possible. For information on establishing a named scholarship at Manhattan School of Music, please contact Susan Madden, Vice President for Advancement, at 917-493-4115 or [email protected]. ABOUT LILLIAN FUCHS Hailed by Harold C. Schonberg in the New York Times in 1962 as “one of the best string players in America,” Lillian Fuchs (1902–1995) joined the chamber music and viola faculties at Manhattan School of Music in 1962, where she remained for almost 30 years. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 31 No. 1, Spring 2015

New Horizons Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements, Part II The Viola Concertos of J. G. Graun and M. H. Graul Unconfused The Absolute Zero Viola Quartet Volume 31 Number 1 Number 31 Volume Turn-Out in Standing Journal of the American Viola Society Viola American the of Journal Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2015: Volume 31, Number 1 p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 9 Primrose Memorial Concert 2015 Myrna Layton reports on Atar Arad’s appearance at Brigham Young University as guest artist for the 33rd concert in memory of William Primrose. p. 13 42nd International Viola Congress in Review: Performing for the Future of Music Martha Evans and Lydia Handy share with us their experiences in Portugal, with a congress that focused on new horizons in viola music. Feature Articles p. 19 Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part II After a fascinating look at Borisovsky’s life in the previous issue, Elena Artamonova delves into the violist’s arrangements and editions, with a particular focus on the Glinka’s viola sonata p. 31 The Viola Concertos of J.G. Graun and M.H. Graul Unconfused The late Marshall ineF examined the viola concertos of J. G. Graul, court cellist for Frederick the Great, in arguing that there may have been misattribution to M. H. Graul. Departments p. 39 With Viola in Hand: A Passion Absolute–The Absolute Zero Viola Quartet The Absolute eroZ Quartet has captured the attention of violists in some 60 countries. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

Lillian Fuchs: Violist, Teacher and Composer

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Lillian Fuchs: violist, teacher and composer; musical and pedagogical aspects of the 16 Fantasy études for viola Teodora Dimova Peeva Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Peeva, Teodora Dimova, "Lillian Fuchs: violist, teacher and composer; musical and pedagogical aspects of the 16 Fantasy études for viola" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3589. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3589 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LILLIAN FUCHS: VIOLIST, TEACHER, AND COMPOSER; MUSICAL AND PEDAGOGICAL ASPECTS OF THE 16 FANTASY ÉTUDES FOR VIOLA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Teodora Peeva B.M., University of California, 2003 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2006 May, 2011 TO THE MEMORY OF MY PARENTS ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To David and the entire Weill family, for your unflagging encouragement and support. To Ms. Lori Patterson, for selflessly sharing your wisdom with me and for allowing me the pleasure of knowing you. My deepest gratitude goes to the members of my doctoral committee, for your contribution of time and knowledge in assisting with the completion of this monograph and for your willingness to serve. -

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours. -

ZIYU SHEN, Violist

ZIYU SHEN, violist “Teenager Ziyu Shen is already making her mark on the music scene. Her recital at London’s Royal Festival Hall won a standing ovation.” —Isle of Man Courier “Tonight’s program offered an ideal opportunity to experience this delightful young artist’s prodigious talent. We were treated to a wonderful performance, played superbly.“ —Oberon’s Grove “Besides her flawless technique, Ziyu is very communicative and has a soul of a real artist.” —Gidon Kremer First Prize, 2014 Young Concert Artists International Auditions The Sander Buchman Prize • The University of Florida Performing Arts Prize First Prize, 2013 Lionel Tertis International Viola Competition First Prize, 2012 Chamber Music Competition of Morningside Bridge Chamber Music Competition in Canada First Prize, 2011 Johansen International Competition for Young String Players in Washington, DC YOUNG CONCERT ARTISTS, INC. 1776 Broadway, Suite 1500 New York, NY 10019 Telephone: (212) 307-6655 Fax: (212) 581-8894 [email protected] www.yca.org Photo: Matt Dine Young Concert Artists, Inc. 1776 Broadway, Suite 1500, New York, NY 10019 telephone: (212) 307-6655 fax: (212) 581-8894 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.yca.org ZIYU SHEN, viola 20-year-old violist Ziyu Shen began to play the violin at age of four and switched to the viola at the age of 12 while studying with Li Sheng at the Music School affiliated with the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. Among her upcoming concerts, Ms. Shen appears at the PyeongChang Festival, as soloist with the Long Bay Symphony and in recitals at Coastal Carolina University and the Musée du Louvre. -

Lunchtime Concert in Europe, Scandinavia, China, the U.S

Rob Nairn worked as Associate Professor of Double Bass at Melbourne Conservatorium and Head of the Early Music Department for the past three years. He previous taught on the faculty of the Juilliard School for 11 years and Penn State University for 18 years where he was a Distinguished Professor. A Past-president of the International Society of Bassists he hosted the Society’s 2009 Convention at Penn State. Rob received his Bachelor of Music with distinction from the Canberra School of Music and a post-graduate diploma from the Berlin Musikhochschule by courtesy of a two-year DAAD German Government Scholarship. His teachers have included Klaus Stoll, Tom Martin, and Max McBride. In 2008 he was awarded a Howard Foundation Fellowship from Brown University. Rob has performed with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, the London Philharmonic, the English, Scottish and Australian Chamber Orchestras, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, The Oslo Philharmonic, The Gothenburg Symphony, The Baltimore Symphony, The Halle Orchestra, the London Sinfonietta, and the Sydney, Adelaide, Queensland and Melbourne Symphony Orchestras, the Australia Ensemble, The Australian World Orchestra and the Australian String Quartet. Rob has recorded for Deutsche Grammaphon, Sony Classical , EMI, Naxos, Tall Poppies, RCA and ABC Classics. In Historical Performance he is currently principal bass with the Australian Brandenburg Orchestra and the Handel Haydn Society of Boston and has worked with the Boston Early Music Festival, Juilliard Baroque, Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique, English Baroque Soloists, Smithsonian Chamber Players, Concerto Caledonia, Ironwood, Washington Bach Consort, the Aulos Ensemble, Rebel, Florilegium and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. -

International Viola Congress

CONNECTING CULTURES AND GENERATIONS rd 43 International Viola Congress concerts workshops| masterclasses | lectures | viola orchestra Cremona, October 4 - 8, 2016 Calendar of Events Tuesday October 4 8:30 am Competition Registration, Sala Mercanti 4:00 pm Tymendorf-Zamarra Recital, Sala Maffei 9:30 am-12:30 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 4:00 pm Stanisławska, Guzowska, Maliszewski 10:00 am Congress Registration, Sala Mercanti Recital, Auditorium 12:30 pm Openinig Ceremony, Auditorium 5:10 pm Bruno Giuranna Lecture-Recital, Auditorium 1:00 pm Russo Rossi Opening Recital, Auditorium 6:10 pm Ettore Causa Recital, Sala Maffei 2:00 pm-5:00 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 8:30 pm Competition Final, S.Agostino Church 2:00 pm Dalton Lecture, Sala Maffei Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 3:00 pm AIV General Meeting, Sala Mercanti 5:10 pm Tabea Zimmermann Master Class, Sala Maffei Friday October 7 6:10 pm Alfonso Ghedin Discuss Viola Set-Up, Sala Maffei 9:00 am ESMAE, Sala Maffei 8:30 pm Opening Concert, Auditorium 9:00 am Shore Workshop, Auditorium Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 10:00 am Giallombardo, Kipelainen Recital, Auditorium Wednesday October 5 11:10 am Palmizio Recital, Sala Maffei 12:10 pm Eckert Recital, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Kosmala Workshop, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Cuneo Workshop, Auditorium 12:10 pm Rotterdam/The Hague Recital, Auditorium 10:00 am Alvarez, Richman, Gerling Recital, Sala Maffei 1:00 pm Street Concerts, Various Locations 11:10 am Tabea Zimmermann Recital, Museo del Violino 2:00 pm Viola Orchestra -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

CCMA Coleman Competition (1947-2015)

THE COLEMAN COMPETITION The Coleman Board of Directors on April 8, 1946 approved a Los Angeles City College. Three winning groups performed at motion from the executive committee that Coleman should launch the Winners Concert. Alice Coleman Batchelder served as one of a contest for young ensemble players “for the purpose of fostering the judges of the inaugural competition, and wrote in the program: interest in chamber music playing among the young musicians of “The results of our first chamber music Southern California.” Mrs. William Arthur Clark, the chair of the competition have so far exceeded our most inaugural competition, noted that “So far as we are aware, this is sanguine plans that there seems little doubt the first effort that has been made in this country to stimulate, that we will make it an annual event each through public competition, small ensemble chamber music season. When we think that over fifty performance by young people.” players participated in the competition, that Notices for the First Annual Chamber Music Competition went out the groups to which they belonged came to local newspapers in October, announcing that it would be held from widely scattered areas of Southern in Culbertson Hall on the Caltech campus on April 19, 1947. A California and that each ensemble Winners Concert would take place on May 11 at the Pasadena participating gave untold hours to rehearsal Playhouse as part of Pasadena’s Twelfth Annual Spring Music we realize what a wonderful stimulus to Festival sponsored by the Civic Music Association, the Board of chamber music performance and interest it Education, and the Pasadena City Board of Directors. -

Dissertation First Pages

Dissertation in Music Performance by Joachim C. Angster A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Dissertation Committee: Assistant Professor Caroline Coade, Co-Chair Professor David Halen, Co-Chair Professor Colleen Conway Associate Professor Max Dimoff Professor Daniel Herwitz Joachim C. Angster [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2563-2819 © Joachim C. Angster 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to members of my Doctoral Committee and to my teacher Professor Caroline Coade in particular, for making me a better musician. I also would like to give special thanks to my collaborators Arianna Dotto, Meridian Prall, Ji-Hyang Gwak, Taylor Flowers, and Nathaniel Pierce. Finally, I am grateful for the continuous support of my parents, and for the invaluable help of Anna Herklotz and Gabriele Dotto. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv FIRST DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 1 Program Notes 2 SECOND DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 18 Program Notes 19 THIRD DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 27 Program Notes 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 iii ABSTRACT This dissertation pertains to three viola recitals, which were respectively performed on 2 October 2019, 20 January 2020, and 9 March 2020. Each recital program embraced a specific theme involving little-performed works as well as staples from the viola repertoire, and covered a wide range of different musical styles. The first recital, performed with violinist Arianna Dotto, focused on violin and viola duo repertoire. Two pieces in the Classical and early Romantic styles by W. A. Mozart and L. -

El Clarinete En Inglaterra: Frederick Thurston (1901-1953)

ESCUELA DE DOCTORADO Facultad de Formación de Profesorado y Educación Programa de Doctorado en Educación TESIS DOCTORAL EL CLARINETE EN INGLATERRA: FREDERICK THURSTON (1901-1953) Autora: Cristina María Strike Campuzano Directores: Dr. Enrique Muñoz Rubio Dr. Carlos Javier Fernández Cobo FEBRERO DE 2018 Agradecimientos A los directores de tesis, el Dr. Enrique Muñoz Rubio y el Dr. Carlos Javier Fernández Cobo por el apoyo recibido y por guiarme en este proyecto. A la familia Davis: Howard, Rachel, Rachel-Emily, Theo, Timothy, Phillip, Thomas y el recién nacido Leo, por su hospitalidad desbordante y por hacerme pasar varios de los mejores meses de mi vida. A la Dra. Helena Gaunt y Kate McNamara, por permitirme sin condiciones la estancia académica en Londres. A los entrevistados: Colin Bradbury, por su ayuda constante, su generosidad y por posibilitarme todos los documentos de los que él disponía sobre Frederick Thurston; Michael Harris por su amabilidad; Janet Hilton por su experiencia; Colin Lawson por su tiempo; Julian Farrell por enseñarme tanto; y Joy Farrall y Neil Black por su amor hacia Thea. A la British Library por hacerme descubrir múltiples posibilidades de conocimiento en la investigación. A la biblioteca de la Guildhall School of Music & Drama: Knut, Kate, Ainara, Rebecca y Adrian, por la inmensa ayuda recibida; a Paul Campion y David Herbert de la Worshipful Company of Musicians; a Margaret Jones del departamento de música de la biblioteca de la Universidad de Cambridge; a Martin Holmes y Juliet Chadwick de la facultad de