AC Haddon On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and References

NOTES AND REFERENCES PREFACE 1 In the period of history covered by the present work, the words most commonly used to describe the type of society studied by anthropologists were "primitive" and "savage". Since however, neither of these words can be used without strongly pejorative overtones, I have done my best to avoid them, substituting instead more emotionally neutral words like "aboriginal", "indigenous" and "preliterate". None of these words is perfectly suited to the job at hand and the result may sometimes come out sounding rather oddly. Nonetheless, I would rather be guilty of minor offences of usage than of encouraging Eurocentric prejudice. 2 Peter Lawrence, "The Ethnographic Revolution", Oceanill45, 253-271 (1975). 3 A recent work which makes a start in this direction is Perspectives on the Emergence of Scientific Disciplines, Gerard Lemaine, Roy MacLeod, Michael Mulkay and Peter Weingart (eds.), (The Hague and Chicago, 1977). From our point of view the most inter esting contribution is Michael Worboy's study of British tropical medicine, a discipline which, largely because of its relationship to British imperialism, exhibited a maturation process which bore many similarities to that of British Social Anthropology. 4 Jairus Banaji, ''The Crisis of British Social Anthropology", New Left Review 64, 75 (Nov.-Dec. 1970). 5 E. E. Evans-Pritchard's famous 1940 ethnography on The Nuer, for example, often regarded as the ultimate achievement of British Social Anthropology, presents the Nuer as a self-contained, static and harmoniously-operating group. However, it is evident from a number of things which Evans-Pritchard mentions in passing that, in fact, the Nuer interact so substantially with the neighbouring Dinka people that, instead of reifying "the Nuer" as a self-contained social entity, it may well have been more sensible to write a book about the Nuer-Dinka complex. -

Lavin Poster (NHRE 2011)

Exploring the Relations and Collections of A.C. Haddon at the Smithsonian Institution Luke Lavin, Amherst College, Amherst, MA Joshua A. Bell, Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC What do the National Museum of Natural Histories’ collections from A.C. Haddon’s General Makeup of the Alfred C. Localities of Torres Strait Collections Analysis and Findings: The dugong charm, tobacco pipe, and first voyage (1888-9) to the Torres Strait tell us about Haddon and local Torres Strait related photos show how objects in the Smithsonian collection can be used to aid in communities’ trade relationships and agencies? 4% Haddon Collections at the Western Islands- Badu, Moa, retracing Haddon’s interaction with locals (e.g., Waria and Gabia) and Europeans 9% Mabuiag, Muralug, Giralag, Kiriri, (e.g., Milman and Beardmore) stationed in the area. The histories of these objects, Smithsonian Ngurapai, Waiben, Maurura: 19 Alfred Cort Haddon (1855-1940) went to the Torres Strait Islands in 1888 to examine marine items and their movements, give us a glimpse into the trade relationships between the Background: Northern Islands- Boigu, Buru, biology and reef systems. Transformed by the experience, Haddon returned in 1898 as head of the Cambridge 7% Dauan, Saibai, Daru, Bobo, Parama: seafaring Islanders, New Guineans, and Cape York Aboriginal communities in 4 items Anthropological Expedition, which revolutionized anthropological field methodologies and helped establish British 1% addition to the customs Haddon sought to “salvage” through his work. The objects Eastern Islands- Mer, Dauar, Waier, Social Anthropology (Herle & Rouse 1998). 42% Erub, Ugar: 13 items themselves speak to the transforming material realities of the region, and the ways in which islanders incorporated external materials in their shifting practices (Fig. -

The Ethnographic Experiment in Island Melanesia ♦L♦

Introduction The Ethnographic Experiment in Island Melanesia ♦l♦ Edvard Hviding and Cato Berg Anthropology in the Making: To the Solomon Islands, 1908 In 1908, three British scholars travelled, each in his own way, to the south-western Pacific in order to embark on pioneering anthropological fieldwork in the Solomon Islands. They were William Halse Rivers Rivers, Arthur Maurice Hocart and Gerald Camden Wheeler. Rivers (1864–1922), a physician, psychologist and self-taught anthropologist, was already a veteran fieldworker, having been a member of the Cambridge Torres Strait Expedition for seven months in 1898 (Herle and Rouse 1998), after which he had also carried out five months of fieldwork among the tribal Toda people of South India in 1901–2 (see Rivers 1906). The Torres Strait Expedition was a large-scale, multi-disciplinary effort with major funding, and had helped change a largely embryonic, descrip- tive anthropology into a modern discipline – reflective of the non-anthro- pological training of expedition leader Alfred Cort Haddon and his team, among whom Rivers and C.G. Seligman were to develop anthropological careers. During the expedition, Rivers not only engaged in a wide range of observations based on his existing training in psychology and physiology, but also increasingly collected materials on the social organisation of the Torres Strait peoples, work that ultimately resulted in him devising the ‘genealogical method’ for use by the growing discipline of anthropology, with which he increasingly identified. 2 Edvard Hviding and Cato Berg ♦ The 1908 fieldwork in Island Melanesia which is the focus of this book was on a much smaller scale than the Torres Strait Expedition, but it had 1 a more sharply defined anthropological agenda. -

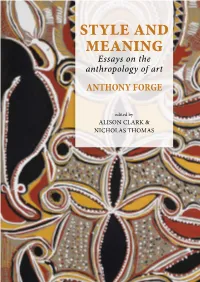

Style and Meaning Anthropology’S Engagement with Art Has a Complex and Uneven History

NICHOLAS THOMAS THOMAS NICHOLAS & CLARK ALISON style and meaning Anthropology’s engagement with art has a complex and uneven history. While style and material culture, ‘decorative art’, and art styles were of major significance for ( founding figures such as Alfred Haddon and Franz Boas, art became marginal as the EDS meaning discipline turned towards social analysis in the 1920s. This book addresses a major ) moment of renewal in the anthropology of art in the 1960s and 1970s. British Essays on the anthropologist Anthony Forge (1929-1991), trained in Cambridge, undertook fieldwork among the Abelam of Papua New Guinea in the late 1950s and 1960s, anthropology of art and wrote influentially, especially about issues of style and meaning in art. His powerful, question-raising arguments addressed basic issues, asking why so much art was produced in some regions, and why was it so socially important? style ANTHONY FORGE meaning Fifty years later, art has renewed global significance, and anthropologists are again considering both its local expressions among Indigenous peoples and its new global circulation. In this context, Forge’s arguments have renewed relevance: they help and edited by scholars and students understand the genealogies of current debates, and remind us of fundamental questions that remain unanswered. ALISON CLARK & NICHOLAS THOMAS This volume brings together Forge’s most important writings on the anthropology anthropology of art Essays on the of art, published over a thirty year period, together with six assessments of his legacy, including extended reappraisals of Sepik ethnography, by distinguished anthropologists from Australia, Germany, Switzerland and the United Kingdom Anthony Forge was born in London in 1929. -

The Language of String Figure-Making in a Sepik Society in Papua New Guinea

Vol. 14 (2020), pp. 598–641 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24964 Revised Version Received: 2 Aug 2020 Talking about strings: The language of string figure-making in a Sepik society in Papua New Guinea Darja Hoenigman The Australian National University The practice of making string figures, often called cat’s cradle, can be found all over the world and is particularly widespread in Melanesia. It has been studied by anthropologists, linguists and mathematicians. For the latter, the ordered series of moves and the resultant string figures represent cognitive processes that form part of a practice of recreational mathematics. Modern anthropology is interested in the social and cultural aspects of string figures, including their associations with other cultural practices, with the local mythology and songs. Despite this clear link to language, few linguists have studied string figures, and those who have, have mainly focused on the songs and formulaic texts that accompany them. Based on a systematic study of string figures among the Awiakay, the inhabitants of Kanjimei village in the Sepik region of Papua New Guinea, with six hours of transcribed video recordings of the practice, this paper argues that studying string figure-making can be an important aspect of language documentation – notjust through the recording and analysis of the accompanying oral literature, but also as a tool for documenting other speech genres through recordings of the naturalistic speech that surrounds string figure-making performances. In turn, analysing the language associated with string figure-making offers valuable insights into the meaning of string figures as understood by their makers. -

Telling Pacific Lives

TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS Brij V. Lal & Vicki Luker Editors Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/tpl_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Telling Pacific lives : prisms of process / editors, Vicki Luker ; Brij V. Lal. ISBN: 9781921313813 (pbk.) 9781921313820 (pdf) Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Islands of the Pacific--Biography. Islands of the Pacific--Anecdotes. Islands of the Pacific--Civilization. Islands of the Pacific--Social life and customs. Other Authors/Contributors: Luker, Vicki. Lal, Brij. Dewey Number: 990.0099 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover image: Choris, Louis, 1795-1828. Iles Radak [picture] [Paris : s.n., [1827] 1 print : lithograph, hand col.; 20.5 x 26 cm. nla.pic-an10412525 National Library of Australia Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Table of Contents Preface vii 1. Telling Pacic Lives: From Archetype to Icon, Niel Gunson 1 2. The Kila Wari Stories: Framing a Life and Preserving a Cosmology, Deborah Van Heekeren 15 3. From ‘My Story’ to ‘The Story of Myself’—Colonial Transformations of Personal Narratives among the Motu-Koita of Papua New Guinea, Michael Goddard 35 4. Mobility, Modernisation and Agency: The Life Story of John Kikang from Papua New Guinea, Wolfgang Kempf 51 5. -

Seeing Art in Objects from the Pacific Around 1900: How Field Collecting and German Armchair Anthropology Met Between 1873 and 19101

Seeing art in objects from the Pacific around 1900: how field collecting and German armchair anthropology met between 1873 and 19101 Christian Kaufmann When reviewing the historical records of how aesthetically remarkable objects of non-European origin came to be considered as art, one is immediately confronted with at least two common myths. Both paint the picture of the ugly anthropologist and, more specifically, of an ethnologist so deprived of aesthetic sensibilities and unable to recognize the artistic quality in these objects from foreign cultures. The argument dates back to the initial period of Primitivism in the first two decades of the 20th century; it was at least partly subscribed to by William Rubin and was at the heart of Jacques Kerchache’s famous 1990 manifesto ‘Pour que les chef-d’oeuvres du monde entier naissent libres et égaux’, which demanded the opening of the Musée du Louvre to the ‘Arts premiers’.2 Accordingly, so the first myth, European artists were the first to immediately see and recognize the artistic value of such works when encountered either in an ethnographic museum, on the wall of a bar, or in a curio-shop. The second myth blames anthropologists of subscribing to vulgar Social-Darwinist views that understood primitive as meaning under-developed, or lower and savage, pending replacement based on the logic of natural selection, that is, evolution, by the ‘true thing’ at least one notch above. In the following I will show that quite the contrary was the case and that early anthropologists, often having been trained as medical doctors or as natural scientists, and visiting local groups in situ, contributed decisively to the recognition and appreciation of the latter’s artistic activities and achievements. -

Evolutionists and Australian Aboriginal Art: 1885- 1915

Evolutionists and Australian Aboriginal art: 1885- 1915 Susan Lowish ...savage art, as of the Australians, develops into barbarous art, as of the New Zealanders; while the arts of strange civilisations, like those of Peru and Mexico, advance one step further... Andrew Lang, 18851 The Idea of Progress2 and the Chain of Being3 greatly influenced the writing about art from ‘other’ countries at the turn of the twentieth century. Together these ideas stood for ‘evolution’, which bore little resemblance to the theories originally propounded by Charles Darwin.4 According to the historian Russell McGregor, ‘Human evolution was...cast into an altogether different shape from organic evolution ... Parallel lines of progress, of unequal length, rather than an ever- ramifying tree, best illustrate the later nineteenth-century conception of human evolution.’5 Several prominent late nineteenth-century anthropologists employed a similar schema in determining theories of the evolution of art. This kind of theorising had a fundamental influence on shaping European perceptions of Aboriginal art from Australia. In 1888, Chambers’s Encyclopaedia began its entry for ‘Art’ with the following: ‘A man in the savage state is one whose whole time is of necessity occupied in getting and retaining the things barely needed to keep him alive.’6 ‘Savages’, as we know through the discourse of ‘hard primitivism’,7 had no time 1 Andrew Lang, Custom and Myth, London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1885, 227. 2 An eighteenth-century belief that advances in science, technology and social organisation would improve the human condition, the Idea of Progress was very influential in many fields of intellectual endevour in the nineteenth century. -

Toward an Ethnography of Experimental Psychology Emily Martin 1

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Plasticity and Pathology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0vc9v8rj ISBN 9780823266135 Authors Bates, David Bassiri, Nima Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Plasticity and Pathology Berkeley Forum in the Humanities Plasticity and Pathology On the Formation of the Neural Subject Edited by David Bates and Nima Bassiri Townsend Center for the Humanities University of California, Berkeley Fordham University Press New York Copyright © 2016 The Regents of the University of California All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publishers. The publishers have no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and do not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. The publishers also produce their books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Plasticity and pathology : on the formation of the neural subject / edited by David Bates and Nima Bassiri. — First edition. p. cm. — (Berkeley forum in the humanities) The essays collected here were presented at the workshop Plasticity and Pathology: History and Theory of Neural Subjects at the Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities at the University of California, Berkeley. -

String Figures and Ethnography

Chapter 2 String Figures and Ethnography 2.1 First Surveys: Context and Issues After his studies at Christ’s College, Cambridge, Alfred Cort Haddon was appointed Professor of Zoology at the College of Science in Dublin. In 1888, he took part as a zoologist in the first expedition to the Torres Strait Islands, located between Papua New Guinea and Australia. It seems that his interest was drawn to both anthropology and string figures during this fieldwork in Oceania: In the summer of 1888 I went to Torres Strait to investigate the structure and fauna of the coral reefs of that district. Very soon after my arrival in the Straits I found that the natives of the islands had of late years been greatly reduced in number, and that, with the exception of but one or two individuals, none of the white residents knew anything about the customs of the natives, and not a single person cared about them personally. [:::]Soitwasmade clear to me that if I neglected to avail myself of the present opportunity of collecting, information on the ethnography of the islanders, it was extremely probable that knowledge would never be gleaned [:::] I felt it my duty to fill up all the time not actually employed in my zoological researches in anthropological studies [:::] (Haddon 1890, pp. 297–298) In 1906, Haddon wrote: In ethnology, as in other sciences, nothing is too insignificant to receive attention. Indeed it is a matter of common experience among scientific men that apparently trivial objects or operations have an interest and importance that are by no means commensurate with the estimation in which they are ordinarily held1 (Jayne 1962,p.v). -

String Figure Bibliography (3Rd Edition, 2000)

CdbY^W 6YWebU 2YR\Y_WbQ`Xi #bT5TYdY_^ 9^dUb^QdY_^Q\ CdbY^W 6YWebU 1cc_SYQdY_^ CdbY^W 6YWebU 2YR\Y_WbQ`Xi Third edition 1`eR\YSQdY_^_VdXU 9^dUb^QdY_^Q\CdbY^W6YWebU1cc_SYQdY_^ IFSA ISFA Press, Pasadena, California Copyright © 2000 by the International String Figure Association. Photocopying of this document for personal use is permitted and encouraged. Published by ISFA Press, P.O. Box 5134, Pasadena, California, 91117, USA. Phone/FAX: (626) 398-1057 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.isfa.org First Edition: December, 1985 (Bulletin of String Figures Association No. 12, Tokyo) Second Edition: May, 1996 Third Edition: January, 2000 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00-102809 ISBN 0-9651467-5-8 $19.95 Foreword It is with great pleasure that I introduce the third edition of String Figure Bibliography, compiled by Dr. Tom Storer. Over 500 new entries have been added since the second edition appeared in 1996. Of the 1862 total entries, 341 include illustrations of string figures and instructions for making them, 372 include illustrations only, and 19 include instructions only (no illustrations). The remaining entries document other aspects of string figures as described below. Each entry is prefaced by a symbol that identifies the type of information it contains: ⇒ An arrow indicates that the cited work includes both string figure illustra- tions and instructions.These are, of course, the classic source documents of the string figure literature, highly sought after by anyone wishing to pursue comparative studies or augment their personal repertoire of figures. A square indicates that the cited work includes instructions for making string figures, but lacks illustrations. -

A New Symbolic Writing for Encoding String Figure Procedures

A New Symbolic Writing for Encoding String Figure Procedures Eric Vandendriessche∗ University of Paris Science-Philosophy-History, UMR 7219, CNRS, F-75205 Paris, France February 27, 2020 Abstract In this article, we present a new symbolic writing for encoding string figure processes. This coding system aims to rewrite the string figure procedures as mathematical formulae, focusing on the operations implemented through these procedures. This formal approach to string figure making practices has been developed in order to undertake a systematic comparison of the various string figure corpora (at our disposal), and their statistical treatment in particular. Key Words: String figures, operations, procedures, coding system, modeling. 1 Introduction From the first scientific studies on string figure-making practices—from the 19th century and onwards—a number of anthropologists have attempted to devise suitable and efficient nomen- clatures to record the procedures involved in the making of such figures. The first published nomenclature by Cambridge anthropologists William H. R. Rivers and Alfred C. Haddon (1902), has been used and refined by ethnographers like Diamond Jenness (1886-1969), Honor Maude (1905-2001), James Hornell (1865-1949), and many others who have collected string figures in different societies throughout the 20th century. This method of writing down string fig- ures processes has been further standardized thanks to the work of string figure experts (like ∗CNRS & Université de Paris, Lab. SPHERE, UMR 7219, Case 7093, 5 rue Thomas Mann, 75205 PARIS CEDEX 13, FRANCE. e-mail: [email protected]. 1 Mark Sherman, Will Wirt, Philip Noble, Joseph D’Antoni, among others), all of them mem- bers of the International String Figure Association (ISFA).