BOIGU ISLAND January 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mediating the Imaginary and the Space of Encounter in the Papuan Gulf Dario Di Rosa

7 Mediating the imaginary and the space of encounter in the Papuan Gulf Dario Di Rosa Writing about the 1935 Hides–O’Malley expedition in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, the anthropologist Edward Schieffelin noted that Europeans ‘had a well-prepared category – “natives” – in which to place those people they met for the first time, a category of social subordination that served to dissipate their depth of otherness’.1 However, this category was often nuanced by Indigenous representations of neighbouring communities, producing significant effects in shaping Europeans’ understanding of their encounters. Analysing the narrative produced by Joseph Beete Jukes,2 naturalist on Francis Price Blackwood’s voyage of 1842–1846 on HMS Fly, I demonstrate the crucial role played by Torres Strait Islanders as mediators from afar of European encounters with Papuans along the coast of the Gulf of 1 Schieffelin and Crittenden 1991: 5. 2 Jukes 1847. As Beer (1996) shows, the viewing position of on-board scientists during geographical explorations was a particular one, led by their interests (see, from a different perspective, Fabian (2000) on the relevance of ‘natural history’ as episteme of accounts of explorations). This is a reminder of the high degree of social stratification within the ‘European’ micro-social community of the ship’s crew, a social hierarchy that shaped the texts available to the historians. Although he does not treat the problem of social stratification as such, see Thomas 1994 for a well-argued discussion about the different projects that guided various colonial actors. See also Dening 1992 for vivid case of power relations in the micro-social cosmos of a ship. -

Your Labor Member in the Queensland Parliament

YOUR LABOR MEMBER IN THE QUEENSLAND PARLIAMENT Cape Vork / Douglas / Cooktown / Mareeba: Torres Strait / NPA P: 1800816264 - Fax: 07 40312437 P: 1800802391 - Fax: 07 4069 1620 PO Box 2080, Cairns 4870 PO Box 437, Thursday Island 4875 E: [email protected] E: cook.th [email protected] Submission to the Queensland Competition Authority Level 19 12 Creek Street BRISBANE QLD 4001 REVIEW OF SUN WATER PRICING STRUCTURE Submission to the Queensland Competition Authority by Jason O'Brien MP Member for Cook, on behalf of a constituent who is a Sun Water user, requesting changes to the pricing policy of Sun Water to their customers holding pension concession cards who access sun water for their domestic use only. Under the present Sun Water tariff structure they are able to negotiate how much revenue could be collected from variable and fixed charges. My submission is that Sun Water should be free to offer a Pensioner Water Subsidy Scheme for eligible pensions to reduce the impact of increased water price increases. This concession could be in the form of a rebate similar to the rate rebate scheme which applies across the state off local government rates charges. Sun Water must have the ability to provide water services to the community at a reasonable cost taking into account the most effective way to utilise the resource for the community's benefit. To this end pensions accessing Sun Water's resource purely for domestic use should be considered in a wider public interest context. Prices should be cost reflective and take into account relevant public interest matters such as pensioners accessing their resource In conclusion I submit that Sun Water should be providing a Pensioner Water Subsidy Scheme and the Queensland Competition Authority should recognise this as a public interest issue. -

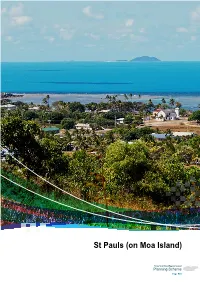

St Pauls (On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.13 St Pauls (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) St Pauls (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 523 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 524 Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa SStt PPaulsauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 525 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • St Pauls is located on the eastern side of Moa • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Island, which is part of the Torres Strait inner and a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing near western group of islands. St Paul’s nearest Range, now separated by sea. The island neighbour is Kubin, which is located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and south-western side of Moa Island. Approximately is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest 15km from the outskirts of St Pauls. point. • Native flora and fauna that have been identified Population near St Pauls include fawn leaf nosed bat, • According to the most recent census, there were grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, 258 people living in St Pauls as at August 2011, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodactylus however, the population is highly transient and primilus, bare backed fruit bat, torresian tube- this may not be an accurate estimate. -

Part 16 Transport Infrastructure Plan

Figure 7.3 Option D – Rail Line from Cairns to Bamaga Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan Masig (Yorke) Island Option D - Rail Line from Cairns to Bamaga Major Roads Moa Island Proposed Railway St Pauls Kubin Waiben (Thursday) Island ° 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 Kilometres Seisia Bamaga Ferry and passenger services as per current arrangements. DaymanPoint Shelburne Mapoon Wenlock Weipa Archer River Coen Yarraden Dixie Cooktown Maramie Cairns Normanton File: J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Mapping\ArcGIS\Workspaces\Option D - Rail Line.mxd 29.07.05 Source of Base Map: MapData Sciences Pty Ltd Source for Base Map: MapData Sciences Pty Ltd 7.5 Option E – Option A with Additional Improvements This option retains the existing services currently operating in the Torres Strait (as per Option A), however it includes additional improvements to the connections between Horn Island and Thursday Island. Two options have been strategically considered for this connection: Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan - Integrated Strategy Report J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Reports\Transport Infrastructure Plan\Transport Infrastructure Plan - Rev I.doc Revision I November 2006 Page 91 • Improved ferry connections; and • Roll-on roll-of ferry. Improved ferry connections This improvement considers the combined freight and passenger services between Cairns, Bamaga and Thursday Island, with a connecting ferry service to OSTI communities. Possible improvements could include co-ordinating fares, ticketing and information services, and also improving safety, frequency and the cost of services. Roll-on roll-off ferry A roll-on roll-off operation between Thursday Island and Horn Island would provide significant benefits in moving people, cargo, and vehicles between the islands. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Meriba Omasker Kaziw Kazipa (Torres Strait Islander Traditional Child Rearing Practice) Bill 2020

Parliamentary Meriba Omasker Kaziw Kazipa (Torres Strait Islander Traditional Child Rearing Practice) Bill 2020 - for our children's children Report No. 40, 56th Parliament Health, Communities, Disability Services and Domestic and Family Violence Prevention Committee August 2020 Health, Communities, Disability Services and Domestic and Family Violence Prevention Committee Chair Mr Aaron Harper MP, Member for Thuringowa Deputy Chair Mr Mark McArdle MP, Member for Caloundra Members Mr Martin Hunt MP, Member for Nicklin Mr Michael Berkman MP, Member for Maiwar Mr Barry O’Rourke MP, Member for Rockhampton Ms Joan Pease MP, Member for Lytton Committee Secretariat Telephone +61 7 3553 6626 Fax +61 7 3553 6699 Email [email protected] Technical Scrutiny +61 7 3553 6601 Secretariat Committee Web Page www.parliament.qld.gov.au/Health Acknowledgements The committee acknowledges the participation of Ms Cynthia Lui MP, Member for Cook at the regional hearings in Bamaga, Thursday Island and Saibai Island from 5 to 7 August 2020. The committee also acknowledges the assistance provided by the Department of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships and the Queensland Parliamentary Library. Images of woven mat provided with courtesy of, and consent from, Ms Isadora Akiba, Saibai Island, on 7 August 2020. Meriba Omasker Kaziw Kazipa (Torres Strait Islander Traditional Child Rearing Practice) Bill 2020 Contents Abbreviations iv Chair’s foreword v Recommendations vi 1 Introduction 1 Role of the committee 1 Inquiry process 2 1.2.1 Recognition -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

Papua New Guinea Ii

The Greater Bird-of-paradise display we witnessed at the km 17 lek in Kiunga was truly unforgettable. PAPUA NEW GUINEA II 12– 28 August / 1 September 2016 LEADER: DANI LOPEZ VELASCO Our second tour to Papua New Guinea – including New Britain - in 2016 was a great success and delivered an unprecedented number of high quality birds. A total of 21 species of Birds-of-paradise (BoPs), - undoubtedly one of the most extraordinary, and “out of this world” bird families in the world, were recorded, perhaps most memorable being a superb male Blue BoP, scoped at close range near Kumul for as long as we wished and showing one of the most vivid blue colours in the animal world. Just as impressive though were spectacular performances by displaying Raggiana and Greater BoPs in excellent light, with up to 8 males lekking at a time, a stunning male King BoP and two displaying males Twelve-wired BoPs at the Elevala River, a cracking adult male Magnificent BoP in the scope for hours at Tabubil, several amazing King-of-Saxony BoPs, waving their incredible head plumes like some strange insect antennae in the mossy forest of Tari Valley, great sightings of both Princess Stephanie´s and Ribbon-tailed Astrapias with their ridiculously long tail feathers, superb scope studies of Black and Brown Sicklebills uttering their machine-gun like calls, and so on. While Birds-of-paradise are certainly the signature family in PNG, there is of course 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Papua New Guinea II www.birdquest-tours.com plenty more besides, for example we recorded a grand total of 33 species of pigeons and doves, -they reach their greatest diversity here in New Guinea, as do kingfishers-, including nine Fruit Doves, a rare New Guinea Bronzewing feeding on the road, and, during the extension, both Black Imperial Pigeon and Pied Cuckoo-Dove. -

Southern Gulf, Queensland

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Part 7 Transport Infrastructure Plan

Sea Transport Safety The marine investigation unit of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) was contacted for information pertaining to recent accidents and incidents with large trading vessels in the region. The data provided related to five incidents that occurred after July 1995 and before 2004: a) A man overboard from the vessel Murshidabad in 1996; b) A close quarters situation between the Maersk Taupo and a small dive runabout off Ackers Shoal Beacon in 1997; c) The grounding of the vessel Thebes on Larpent Bank in 1997; d) The grounding of the vessel Dakshineshwar on Larpent Bank in 1997; and e) The grounding of the vessel NOL Amber on Larpent Bank in 1997. Figure 3.7 shows the location of marine accidents that have occurred in northern Queensland in 2004. Figure 3.7 Location of Marine Accidents in Northern Queensland (2004) Source: MSQ: 2005 Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan - Integrated Strategy Report J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Reports\Transport Infrastructure Plan\Transport Infrastructure Plan - Rev I.doc Revision I November 2006 Page 21 Figure 3.8 Existing Ferry Services Torres Strait Transport Ugar (Stephen) Island Infrastructure Plan Papua New Guinea Ferry Routes ° Saibai (Kaumag) Island Dauan Island Erub (Darnley) Island Map 1 - Saibai (Kaumag) Island to Dauan Island 1:200,000 Map 2 - Ugar (Stephen) Island to Erub (Darnley) Island 1:150,000 Hammond Waiben Map 1 Island (Thursday) Island Map 2 Nguruppai (Horn) Island Muralug (Prince of Wales) Island Map 3 Seisia Seisia Map 3 - Thursday Island 1:300,000 -

Mangroves: Unusual Forests at the Seas Edge

Tropical Forestry Handbook DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-41554-8_129-1 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Mangroves: Unusual Forests at the Seas Edge Norman C. Dukea* and Klaus Schmittb aTropWATER – Centre for Tropical Water and Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia bDepartment of Environment and Natural Resources, Deutsche Gesellschaft fur€ Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Quezon City, Philippines Abstract Mangroves form distinct sea-edge forested habitat of dense, undulating canopies in both wet and arid tropic regions of the world. These highly adapted, forest wetland ecosystems have many remarkable features, making them a constant source of wonder and inquiry. This chapter introduces mangrove forests, the factors that influence them, and some of their key benefits and functions. This knowledge is considered essential for those who propose to manage them sustainably. We describe key and currently recommended strategies in an accompanying article on mangrove forest management (Schmitt and Duke 2015). Keywords Mangroves; Tidal wetlands; Tidal forests; Biodiversity; Structure; Biomass; Ecology; Forest growth and development; Recruitment; Influencing factors; Human pressures; Replacement and damage Mangroves: Forested Tidal Wetlands Introduction Mangroves are trees and shrubs, uniquely adapted for tidal sea verges of mostly warmer latitudes of the world (Tomlinson 1994). Of primary significance, the tidal wetland forests they form thrive in saline and saturated soils, a domain where few other plants survive (Fig. 1). Mangrove species have been indepen- dently derived from a diverse assemblage of higher taxa. The habitat and structure created by these species are correspondingly complex, and their features vary from place to place. For instance, in temperate areas of southern Australia, forests of Avicennia mangrove species often form accessible parkland stands, notable for their openness under closed canopies (Duke 2006). -

Ultimate Papua New Guinea Ii

The fantastic Forest Bittern showed memorably well at Varirata during this tour! (JM) ULTIMATE PAPUA NEW GUINEA II 25 AUGUST – 11 / 15 SEPTEMBER 2019 LEADER: JULIEN MAZENAUER Our second Ultimate Papua New Guinea tour in 2019, including New Britain, was an immense success and provided us with fantastic sightings throughout. A total of 19 Birds-of-paradise (BoPs), one of the most striking and extraordinairy bird families in the world, were seen. The most amazing one must have been the male Blue BoP, admired through the scope near Kumul lodge. A few females were seen previously at Rondon Ridge, but this male was just too much. Several males King-of-Saxony BoP – seen displaying – ranked high in our most memorable moments of the tour, especially walk-away views of a male obtained at Rondon Ridge. Along the Ketu River, we were able to observe the full display and mating of another cosmis species, Twelve-wired BoP. Despite the closing of Ambua, we obtained good views of a calling male Black Sicklebill, sighted along a new road close to Tabubil. Brown Sicklebill males were seen even better and for as long as we wanted, uttering their machine-gun like calls through the forest. The adult male Stephanie’s Astrapia at Rondon Ridge will never be forgotten, showing his incredible glossy green head colours. At Kumul, Ribbon-tailed Astrapia, one of the most striking BoP, amazed us down to a few meters thanks to a feeder especially created for birdwatchers. Additionally, great views of the small and incredible King BoP delighted us near Kiunga, as well as males Magnificent BoPs below Kumul.