UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Pharaonic Egypt Through the Eyes of a European Traveller and Collector

Pharaonic Egypt through the eyes of a European traveller and collector Excerpts from the travel diary of Johann Michael Wansleben (1672-3), with an introduction and annotations by Esther de Groot Esther de Groot s0901245 Book and Digital Media Studies University of Leiden First Reader: P.G. Hoftijzer Second reader: R.J. Demarée 0 1 2 Pharaonic Egypt through the eyes of a European traveller and collector Excerpts from the travel diary of Johann Michael Wansleben (1672-3), with an introduction and annotations by Esther de Groot. 3 4 For Harold M. Hays 1965-2013 Who taught me how to read hieroglyphs 5 6 Contents List of illustrations p. 8 Introduction p. 9 Editorial note p. 11 Johann Michael Wansleben: A traveller of his time p. 12 Egypt in the Ottoman Empire p. 21 The journal p. 28 Travelled places p. 53 Acknowledgments p. 67 Bibliography p. 68 Appendix p. 73 7 List of illustrations Figure 1. Giza, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 104 p. 54 Figure 2. The pillar of Marcus Aurelius, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 123 p. 59 Figure 3. Satellite view of Der Abu Hennis and Der el Bersha p. 60 Figure 4. Map of Der Abu Hennis from the original manuscript p. 61 Figure 5. Map of the visited places in Egypt p. 65 Figure 6. Map of the visited places in the Faiyum p. 66 Figure 7. An offering table from Saqqara, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 39 p. 73 Figure 8. A stela from Saqqara, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 40 p. 74 Figure 9. -

Demoticpapyriandthe

Originalveröffentlichung in: Capasso, Mario/Davoli, Paola (Hg.), Soknopaiou Nesos Project I (2003–2009). Biblioteca degli "Studi di Egittologia e di Papirologia", Pisa/Rom 2012, S. 379–386 CAPITOLO DECIMO INTERPRETING THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE TEMENOS: DEMOTIC PAPYRI AND THE CULT IN SOKNOPAIOU NESOS* MARTIN ANDREAS STADLER** ABSTRACT tailed and systematic palaeographical study of hieroglyphic papyri from the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, it cannot be This article will present papyri that refer to the temple's architec excluded that the papyrus is even Ptolemaic. According to ture and decoration. The material may be divided into two sub Winter the papyrus' function is that it served as a model categories: first, texts that describe the wall's decoration directly, which the craftsmen may have used to carve the inscrip and second, ritual and liturgical texts from which information about the ritually determined architectural layout may be gained tions onto the stone to decorate the gate. However, it is not indirectly. In a third step I will discuss the architectural context in clear whether it was written for the inscription of a naos or which the rituals may have been performed and try to link it to a proper temple gate. Winter favoured the former rather the temple's archaeological remains. The identification of a cult than the latter. If the date of the papyrus is indeed Roman, on the temple's roof and of a contratemple demonstrates that the inscription copied onto the papyrus would be some 100 the temple followed patterns that are common to other Egyptian years older. After having presented two other texts I should temples. -

Read the 34 Letters to Paul Carron. Pgs 187-304

: 8. LETTERS TO PAUL CARRON Paul Carron studied at the Seminary of St. Sulpice in Paris and was quickly noticed on account of his outstanding piety and talents. Immediately after his ordination, he be- came secretary to the Archbishop of Paris. The numerous letters Father Libermann addressed to him indicate the last- ing spiritual friendship between those two zealous men. 123 Trials draw us closer to Jesus. Letter One lssy, September 21, 1836 Vol. 1, p. 324 Dear Confrere May the good Lord preserve you in His peace and most holy love. You probably blame me very much for having received your two letters and not having answered a single one of them. It is unpardonable, isn't it? And yet it is not a great fault on my part. I would have replied immediately after I had received your first letter, but I had to leave a few days later. I thought I would be able to see you before my letter would have reached you, for I reckoned that you would re- main at lssy during the whole Octave, and my letter would have reached your place during your absence. Regarding the second, I wanted absolutely to send you the enclosed papers, and they were not ready at that time. Mr. de la Bruniere. who had the job of copying them, was somewhat behind in his task. Anyhow, provided you love God, and I also, we can both of us be satisfied. I should have been very glad to see you at lssy. One of the reasons why I hastened to leave Strasbourg was that I might come in time; God did not wish it. -

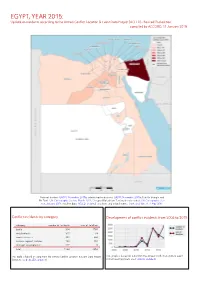

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Paola Davoli

Papyri, Archaeology, and Modern History Paola Davoli I. Introduction: the cultural and legal context of the first discoveries. The evaluation and publication of papyri and ostraka often does not take account of the fact that these are archaeological objects. In fact, this notion tends to become of secondary importance compared to that of the text written on the papyrus, so much so that at times the questions of the document’s provenance and find context are not asked. The majority of publications of Greek papyri do not demonstrate any interest in archaeology, while the entire effort and study focus on deciphering, translating, and commenting on the text. Papyri and ostraka, principally in Greek, Latin, and Demotic, are considered the most interesting and important discoveries from Greco-Roman Egypt, since they transmit primary texts, both documentary and literary, which inform us about economic, social, and religious life in the period between the 4th century BCE and the 7th century CE. It is, therefore, clear why papyri are considered “objects” of special value, yet not archaeological objects to study within the sphere of their find context. This total decontextualization of papyri was a common practice until a few years ago though most modern papyrologists have by now fortunately realized how serious this methodological error is for their studies.[1] Collections of papyri composed of a few dozen or of thousands of pieces are held throughout Europe and in the United States. These were created principally between the end of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, a period in which thousands of papyri were sold in the antiquarian market in Cairo.[2] Greek papyri were acquired only sporadically and in fewer numbers until the first great lot of papyri arrived in Cairo around 1877. -

Pollen Atlas of the Flora of Egypt 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae

Pollen Atlas of the flora of Egypt * 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae Nahed El-Husseini and Eman Shamso. The Herbarium, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza 12613, Egypt. El-Husseini, N. & Shamso, E. 2002. The pollen atlas of the flora of Egypt. 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae. Taeckholmia 22(1): 65-76. Light and scanning electron microscope study of the pollen grains of 47 species representing 16 genera of Scrophulariaceae in Egypt was carried out. Pollen grains vary from subspheroidal to prolate; trizonocolpate to trizonocolporate. Exine’s sculpture is striate, colliculate, granulate, coarse reticulate or microreticulate. Seven pollen types are recognized and briefly described, a key distinguishing the different pollen types and the discussion of its systematic value are provided. Key words: Flora of Egypt, pollen atlas, Scrophulariaceae. Introduction The Scrophulariaceae is a family of about 292 genera and nearly 3000 species of cosmopolitan distribution. It is represented in the flora of Egypt by 50 species belonging to 16 genera, 8 tribes and 3 sub-families (El-Hadidi et al., 1999). Within the family, a wide range of pollen morphology exists and provides not only an additional parameter for generic delimitation but also reinforces the validity of many of the larger taxa. Erdtman (1952), gave a concise account of the pollen morphology of some members of the family. Several authors studied and described the pollen of species of the family among whom to mention: Risch (1939), Ikuse (1956), Natarajan (1957), Verghese (1968), Olsson (1974), Elisens (1985c & 1986), Bolliger & Wick (1990) and Argu (1980, 1990 & 1993). Material and Methods Pollen grains of 47 species representing 16 genera of Scrophulariaceae were the subject of the present investigation. -

Davoli the Temple of Soknopaios and Isis Nepherses at Soknopaiou Nesos (El-Fayyum) 51-68

Université Paul Valéry (Montpellier III) – CNRS UMR 5140 « Archéologie des Sociétés Méditerranéennes » Équipe « Égypte Nilotique et Méditerranéenne » (ENiM) CENiM 9 Cahiers de l’ENiM Le myrte et la rose Mélanges offerts à Françoise Dunand par ses élèves, collègues et amis Réunis par Gaëlle Tallet et Christiane Zivie-Coche * Montpellier, 2014 © Équipe « Égypte Nilotique et Méditerranéenne » de l’UMR 5140, « Archéologie des Sociétés Méditerranéennes » (Cnrs – Université Paul Valéry – Montpellier III), Montpellier, 2014 Françoise Dunand à sa table de travail, à l’Institut d’histoire des religions de l’Université de Strasbourg, dans les années 1980 (d. r.). TABLE DES MATIÈRES Volume 1 Table des matières I-III Abréviations bibliographiques V-VIII Liste des contributeurs IX Introduction Gaëlle Tallet et Christiane Zivie-Coche D’une autre rive. Entretiens avec Françoise Dunand XI-XIX Gaëlle Tallet Bibliographie de Françoise Dunand XXI-XXVII I. La société égyptienne au prisme de la papyrologie Adam Bülow-Jacobsen Texts and Textiles on Mons Claudianus 3-7 Hélène Cuvigny « Le blé pour les Juifs » (O.Ka.La. Inv. 228) 9-14 Arietta Papaconstantinou Egyptians and ‘Hellenists’ : linguistic diversity in the early Pachomian monasteries 15-21 Jean A. Straus Esclaves malfaiteurs dans l'Égypte romaine 23-31 II. Le ‘cercle isiaque’ Corinne Bonnet Stratégies d’intégration des cultes isiaques et du culte des Lagides dans la région de Tyr à l’époque hellénistique 35-40 Laurent Bricault Les Sarapiastes 41-49 Paola Davoli The Temple of Soknopaios and Isis Nepherses at Soknopaiou Nesos (El-Fayyum) 51-68 Michel Reddé Du Rhin au Nil. Quelques remarques sur le culte de Sarapis dans l’armée romaine 69-75 III. -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

The Birth of Territory

the birth of territory The Birth of Territory stuart elden the university of chicago press chicago and london Stuart Elden is professor of political theory and geography at the University of Warwick. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2013 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2013. Printed in the United States of America 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5 isbn-13: 978-0-226-20256-3 (cloth) isbn-13: 978-0-226-20257-0 (paper) isbn-13: 978-0-226-04128-5 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Elden, Stuart, 1971- The birth of territory / Stuart Elden. pages. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-226-20256-3 (cloth : alk. paper)—isbn 978-0-226-20257-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)—isbn 978-0-226-04128-5 (e-book) 1. Political geography. 2. Geography, Ancient. 3. Geography, Medieval. I. Title. jc319.e44 2013 320.1’2—dc23 2013005902 This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 Part I 19 1. The Polis and the Khora 21 Autochthony and the Myth of Origins 21 Antigone and the Polis 26 The Reforms of Kleisthenes 31 Plato’s Laws 37 Aristotle’s Politics 42 Site and Community 47 2. From Urbis to Imperium 53 Caesar and the Terrain of War 55 Cicero and the Res Publica 60 The Historians: Sallust, Livy, Tacitus 67 Augustus and Imperium 75 The Limes of the Imperium 82 Part II 97 3. -

On the Demise of Egyptian Writing: Working with a Problematic Source Basis

Originalveröffentlichung in: Baines, John /Bennet, John / Houston, Stephen (Hg.), The disappearance of writing systems: Perspectives on literacy and communication, London 2008, S.157–181 On the Demise of Egyptian Writing: Working with a Problematic Source Basis Martin Andreas Stadler For the study of the end of Egyptian writing Systems, demotic is of special rel- evance, because Egyptian texts continued to be notated in demotic long after other Egyptian Scripts were abandoned ('Demotic' refers to the Egyptian lan- guage of 650 BC onwards and 'demotic' to the Script). The demotic Philae graf- fiti are the latest of all Egyptian inscriptions. Therefore the focus should lie on demotic, which underwent dramatic changes from being originally an everyday script to one that became perfectly acceptable for religious texts. However, the case of hieroglyphic and its demise is also revealing and should be compared to the end of demotic. I therefore discuss the following topics: After summarizing the models that Egyptologists have proposed for interpreting the disappearance of Egyptian Scripts and culture, I discuss briefly the ups and downs of Egyptian writing competence throughout Egyptian history. I then ask whether avail- able sources and data allow us to draw definite conclusions. I explore in some detail the impact of increasing complexity in hieroglyphic temple inscriptions in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods in the wider context of the development of intellectual trends in that epoch. Finally, I reflect on whether demotic followed the same trajectory as hieroglyphic when it applied so-called unetymological or phonetic writings, which turned demotic into a script of restricted knowledge. -

A Comparative Study of the Concept of Atonement in The

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2015 A Comparative Study of the Concept of Atonement in the Aboakyer Festival of the Effutu Tribe in Ghana and the Yom Kippur Festival of the Old Testament: Implications for Adventist Mission Among the Effutu Emmanuel H. Takyi Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Takyi, Emmanuel H., "A Comparative Study of the Concept of Atonement in the Aboakyer Festival of the Effutu Tribe in Ghana and the Yom Kippur Festival of the Old Testament: Implications for Adventist Mission Among the Effutu" (2015). Dissertations. Paper 1575. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE CONCEPT OF ATONEMENT IN THE ABOAKYER FESTIVAL OF THE EFFUTU TRIBE IN GHANA AND THE YOM KIPPUR FESTIVAL OF THE OLD TESTAMENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR ADVENTIST MISSION AMONG THE EFFUTU by Emmanuel H. Takyi Chair: Gorden R. Doss ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE ATONEMENT CONCEPT IN THE ABOAKYER FESTIVAL OF THE EFFUTU TRIBE IN GHANA AND THE YOM KIPPUR FESTIVAL OF THE OLD TESTAMENT: IMPLICATION FOR ADVENTIST MISSION AMONG THE EFFUTU Name of researcher: Emmanuel H. Takyi Name and degree of faculty adviser: Gorden R.