The Unraveling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Pdf 707.34 KB

NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION IN OR INTO OR TO ANY PERSON LOCATED OR RESIDENT IN THE UNITED STATES, ITS TERRITORIES AND POSSESSIONS, ANY STATE OF THE UNITED STATES OR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA (INCLUDING PUERTO RICO, THE U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS, GUAM, AMERICAN SAMOA, WAKE ISLAND AND THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS) OR IN OR INTO OR TO ANY PERSON LOCATED OR RESIDENT IN ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DISTRIBUTE THIS DOCUMENT. EXOR N.V. ANNOUNCES FINAL RESULTS OF ITS TENDER OFFERS Amsterdam, 20 January 2021. EXOR N.V. (the Company) hereby announces the final results of its invitations to eligible Noteholders of its €750,000,000 2.125 per cent. Notes due 2 December 2022, ISIN XS1329671132 (of which €750,000,000 is currently outstanding) (the 2022 Notes) and its €650,000,000 2.50 per cent. Notes due 8 October 2024, ISIN XS1119021357 (of which €650,000,000 is currently outstanding) (the 2024 Notes, and together with the 2022 Notes, the Notes and each a Series) to tender their Notes for purchase by the Company for cash up to an aggregate maximum acceptance amount of €400,000,000 in aggregate nominal amount (the Maximum Acceptance Amount) (such invitations, the Offers and each an Offer). The Offers were announced on 12 January 2021 and were made on the terms and subject to the conditions set out in the tender offer memorandum dated 12 January 2021 (the Tender Offer Memorandum) prepared in connection with the Offers, and subject to the offer and distribution restrictions set out in the Tender Offer Memorandum. -

The Corporate Governance Lessons from the Financial Crisis

ISSN 1995-2864 Financial Market Trends © OECD 2009 Pre-publication version for Vol. 2009/1 The Corporate Governance Lessons from the Financial Crisis Grant Kirkpatrick * This report analyses the impact of failures and weaknesses in corporate governance on the financial crisis, including risk management systems and executive salaries. It concludes that the financial crisis can be to an important extent attributed to failures and weaknesses in corporate governance arrangements which did not serve their purpose to safeguard against excessive risk taking in a number of financial services companies. Accounting standards and regulatory requirements have also proved insufficient in some areas. Last but not least, remuneration systems have in a number of cases not been closely related to the strategy and risk appetite of the company and its longer term interests. The article also suggests that the importance of qualified board oversight and robust risk management is not limited to financial institutions. The remuneration of boards and senior management also remains a highly controversial issue in many OECD countries. The current turmoil suggests a need for the OECD to re-examine the adequacy of its corporate governance principles in these key areas. * This report is published on the responsibility of the OECD Steering Group on Corporate Governance which agreed the report on 11 February 2009. The Secretariat’s draft report was prepared for the Steering Group by Grant Kirkpatrick under the supervision of Mats Isaksson. FINANCIAL MARKET TRENDS – ISSN 1995-2864 - © OECD 2008 1 THE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE LESSONS FROM THE FINANCIAL CRISIS Main conclusions The financial crisis can This article concludes that the financial crisis can be to an be to an important important extent attributed to failures and weaknesses in corporate extent attributed to governance arrangements. -

Goldman Sachs Presentation to Bank of America Merrill Lynch Banking and Financial Services Conference

Goldman Sachs Presentation to Bank of America Merrill Lynch Banking and Financial Services Conference Harvey M. Schwartz Chief Financial Officer November 17, 2015 Cautionary Note on Forward-Looking Statements Today’s presentation and any presentation summary on our website may include forward-looking statements. These statements are not historical facts, but instead represent only the Firm’s beliefs regarding future events, many of which, by their nature, are inherently uncertain and outside of the Firm’s control. It is possible that the Firm’s actual results and financial condition may differ, possibly materially, from the anticipated results and financial condition indicated in these forward-looking statements. For a discussion of some of the risks and important factors that could affect the Firm’s future results and financial condition, see “Risk Factors” in our Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2014. You should also read the forward-looking disclaimers in our Form 10-Q for the quarterly period ended September 30, 2015, particularly as it relates to capital and leverage ratios, and information on the calculation of non-GAAP financial measures that is posted on the Investor Relations portion of our website: www.gs.com. The statements in the presentation are current only as of its date, November 17, 2015. Investing & Lending Segment Debt and Equity Forward Overview Loans Investments Outlook Average Firmwide Net Revenues 2010 to 2015YTD1 Investing & Lending Includes lending to clients across the firm as well as -

The Federal Reserve's Catch-22: 1 a Legal Analysis of the Federal Reserve's Emergency Powers

~ UNC Jill SCHOOL OF LAW *'/(! 4 --/! ,.%'! " ! ! " *''*1.$%-) %.%*)'1*,&-. $6+-$*',-$%+'1/)! /)% ,.*".$! )&%)#) %))!1*((*)- !*((!) ! %..%*) 5*(-*,.!, 7;:9;8;<= 0%''!. $6+-$*',-$%+'1/)! /)%0*' %-- 5%-*.!%-,*/#$..*2*/"*,",!!) *+!)!--2,*'%)1$*',-$%+!+*-%.*,2.$-!!)!+.! "*,%)'/-%*)%)*,.$,*'%) )&%)#)-.%./.!2)/.$*,%3! ! %.*,*",*'%)1$*',-$%+!+*-%.*,2*,(*,!%)"*,(.%*)+'!-!*).. '1,!+*-%.*,2/)! / The Federal Reserve's Catch-22: 1 A Legal Analysis of the Federal Reserve's Emergency Powers I. INTRODUCTION The federal government's role in the buyout of The Bear Stearns Companies (Bear) by JPMorgan Chase (JPMorgan) will be of lasting significance because it shaped a pivotal moment in the most threatening financial crisis since The Great Depression.2 On March 13, 2008, Bear informed "the Federal Reserve and other government agencies that its liquidity position had significantly deteriorated, and it would have to file for bankruptcy the next day unless alternative sources of funds became available."3 The potential impact of Bear's insolvency to the global financial system4 persuaded officials at the Federal Reserve (the Fed) and the United States Department of the Treasury (Treasury) to take unprecedented regulatory action.5 The response immediately 1. JOSEPH HELLER, CATCH-22 (Laurel 1989). 2. See Turmoil in the Financial Markets: Testimony Before the H. Oversight and Government Reform Comm., llO'h Cong. -- (2008) [hereinafter Greenspan Testimony] (statement of Dr. Alan Greenspan, former Chairman, Federal Reserve Board of Governors) ("We are in the midst of a once-in-a century credit tsunami."); Niall Ferguson, Wall Street Lays Another Egg, VANITY FAIR, Dec. 2008, at 190, available at http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2008/12/banks200812 ("[B]eginning in the summer of 2007, [the global economy] began to self-destruct in what the International Monetary Fund soon acknowledged to be 'the largest financial shock since the Great Depression."'); Jeff Zeleny and Edmund L. -

Merrill Edge Select Funds1 Listing Created As of April 26, 2013

Merrill Edge SelectTM Funds Merrill Edge Select Funds1 Listing created as of April 26, 2013. To help simplify your investing experience, Merrill Lynch investment professionals have developed a proprietary screening process based on quantitative analyses for mutual funds offered through Merrill Edge. Each quarter we take into account risk and performance measures to highlight up to five no-load and load waived funds with no transaction fees for each fund category. Generally, no one metric determines the outcome of any selection, and metrics may have different weights in the filtering process. The Merrill Edge Select Funds are ranked by information ratio and displayed alphabetically. Visit merrilledge.com for details on Merrill Edge Select Funds selection criteria. Domestic Equity Fund Name Security Symbol Asset Class Large-Cap Growth JOHN HANCOCK US GLOBAL LEADERS USGLX Domestic Equity GROWTH FD T ROWE PRICE BLUE CHIP GROWTH FD TRBCX Domestic Equity TCW SELECT EQUITIES FUND TGCNX Domestic Equity T ROWE PRICE GROWTH STOCK FUND PRGFX Domestic Equity ALGER SPECTRA FUND SPECX Domestic Equity Large-Cap Value T ROWE PRICE VALUE FUND TRVLX Domestic Equity NUVEEN DIVIDEND VALUE FUND FFEIX Domestic Equity AMERICAN CENTURY INCOME & GROWTH BIGRX Domestic Equity FD NLD JOHN HANCOCK DISCIPLINED VALUE FUND JVLAX Domestic Equity RIDGEWORTH LARGE CAP VALUE EQUITY SVIIX Domestic Equity FUND © 2013 Bank of America Corporation. All rights reserved. I ARD6A740 I 4/2013 Domestic Equity cont. Fund Name Security Symbol Asset Class Mid-Cap Growth HIGHMARK GENEVA -

525000000 Freddie Mac Citigroup Global Markets Inc. Bofa Merrill

PRICING SUPPLEMENT DATED November 13, 2017 (to the Offering Circular Dated February 16, 2017) $525,000,000 Freddie Mac Variable Rate Medium-Term Notes Due August 21, 2018 Issue Date: November 21, 2017 Maturity Date: August 21, 2018 Subject to Redemption: No Interest Rate: See “Description of the Medium-Term Notes” herein Principal Payment: At maturity CUSIP Number: 3134GB4C3 You should read this Pricing Supplement together with Freddie Mac's Global Debt Facility Offering Circular, dated February 16, 2017 (the "Offering Circular"), and all documents that are incorporated by reference in the Offering Circular, which contain important detailed information about the Medium-Term Notes and Freddie Mac. See "Additional Information" in the Offering Circular. Capitalized terms used in this Pricing Supplement have the meanings we gave them in the Offering Circular, unless we specify otherwise. The Medium-Term Notes offered pursuant to this Pricing Supplement are complex and highly structured debt securities that may not pay a significant amount of interest for extended periods of time. The Medium-Term Notes are not a suitable investment for individuals seeking a steady stream of income The Medium-Term Notes may not be suitable investments for you. You should not purchase the Medium-Term Notes unless you understand and are able to bear the yield, market, liquidity and other possible risks associated with the Medium-Term Notes. You should read and evaluate the discussion of risk factors (especially those risk factors that may be particularly relevant to this security) that appears in the Offering Circular under “Risk Factors” before purchasing any of the Medium-Term Notes. -

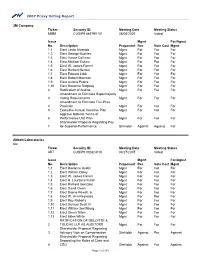

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

Citi Acquisition of Wachovia's Banking Operations

Citi Acquisition of Wachovia’s Banking Operations September 29, 2008 Transaction Structure Transaction Citi acquires Wachovia’s retail bank, corporate and investment bank and private bank Details businesses – Citi pays $2.2 billion to Wachovia in Citi common stock – Citi assumes substantially all of Wachovia’s debt; preferred stock excluded – Wachovia remains a publicly-traded holding company consisting of its retail brokerage and asset management businesses Capital Citi expects to raise $10 billion in common equity from the public markets Citi issues preferred stock and warrants to FDIC with a fair value of $12 billion at closing, accounted for as GAAP equity with full Tier 1 and leverage ratio benefit Quarterly dividend reduced to $0.16 per share immediately Regulatory capital relief on substantially all of the $312 billion of loss protected assets Risk Mitigation Citi enters loss protection arrangement with the FDIC on $312 billion of loss protected assets; maximum potential Citi losses of $42 billion – Citi is responsible for the first $30 billion of losses, recorded at closing through purchase accounting – Citi is responsible for the next $12 billion of losses, up to a maximum of $4 billion per year for the next three years – FDIC is responsible for any additional losses – Citi issues preferred stock and warrants to FDIC with a fair value of $12 billion at closing Approvals FDIC approved; subject to formal Federal Reserve approval and Wachovia shareholder approval Closing Anticipated by December 31, 2008 1 Terms of Loss Protection -

Report of Investigation

REPORT OF INVESTIGATION UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL Investigation into Allegations of Improper Preferential Treatment and Special Access in Connection with the Division of Enforcement's Investigation of Citigroup, Inc. Case No. OIG-559 September 27,2011 This document is subjed to the provisions of th e Privacy Act of 1974, and may require redadion before disdosure to third parties. No redaction has betn performed by the Office of Inspedor Gmeral. Recipients of this report should not disseminate or copy it without the Inspector General's approval. " Report of Investigation Cas. No. OIG-559 Investigation into Allegations of Improper Preferential Treatment and Speeial Access in Connection with the Division of Enforcement's Investigation ofCitigroup, Inc. Table of Contents Introduction and Summary of Results ofthe Investigation ......................................... ..... .. I Scope of the Investigation................................................................................................... 2 Relevant Statutes, Regulations and Pol icies ....................................................................... 4 Results of the Investigation................................................. .. .............................................. 5 I. The Enforcement Staff Investigated Citigroup and Considered Various Charges and Settlement Options ........................................................................................... 5 A. The Enforcement Staff Opened an Investigation -

Bear Stearns High Grade Structured Credit Strategies Fund

Alter~(lv~ Inv<!'Stment M.I~i(,lIlenl AsSO<.iaUon AlMA'S ILLUSTRATIVE QUESTIONNAIRE FOR DUE DILIGENCE OF Bear Stearns High Grade Structured Credit Strategies Fund Published by The Alternative Investment Management Association Limited (AlMA) IMPORTANT NOTE All/any reference to AlMA should be removed from this document once any amendment is made of any question .or information added· including details of a company/fund. Only AlMA can distribute this questionnaire in its current form to its member companies and institutional investors on its confidential database. AlMA's Illustrative Questionnaire for Due Diligence Review of Hedge Fund Managers ~ The Alternative Investment Management Association Limited (AlMA), 2004 1 of 25 Confidential Treatment Requested by JPMorgan BSAMFCIC 00000364 AlMA's Illustrative Questio~naire for Due Diligence Review of HEDGE FUND MANAGERS This due diligence questionnaire is a tool to assist investors when considering a hedge fund manager and a hedge fund. Most hedge fund strategies are more of an investment nature than a trading activity. Each strategy has its own peculiarities. The most important aspect is to understand clearly what you plan to invest in. You will also have to: • identify the markets covered, • understand what takes place in the portfolio, • understand the instruments used and how they are used, • understand how the strategy is operated, • identify the sources of return, • understand how ideas are generated, • check the risk control mechanism, • know the people you invest wIth professionally and, sometimes, personally. Not all of the following questions are applicable to aU managers but we recommend that you ask as many questions as possible before making a dedsion. -

Appendix E: Occ Supervision of Citibank, Na

APPENDIX E: OCC SUPERVISION OF CITIBANK, N.A. I. OCC’s Supervision of Large National Banks The foundation of the OCC’s supervision of the largest national banks is our continuous, on-site presence of examiners at each of our 15 largest banking companies. Citibank is one of the banks in our Large Bank Program. These 15 banking companies account for approximately 89 percent of the assets held in all of the national banks under our supervision. The resident examiner teams are supplemented by subject matter experts in our Policy Division, as well as Ph.D. economists from our Risk Analysis Division trained in quantitative finance. Since 2005, the resident examiner team at Citibank averaged approximately 50 resident examiners, supplemented by the subject matter experts and economists mentioned above, and additional examiners as needed on specific targeted examinations. Our Large Bank Program is organized with a national perspective. It is highly centralized and headquartered in Washington, and structured to promote consistency and coordination across institutions. The onsite teams at each or our 15 largest banks are led by an Examiner-In-Charge (“EIC”), who reports directly to one of the Deputy Comptrollers in our Large Bank Supervision Office in Washington, DC. This enables the OCC to maintain an on- going program of risk assessment, monitoring, and communication with bank management and directors. Resident examiners apply risk-based supervision to a broad array of risks, including credit, liquidity, market, compliance, and operational risks. Supervisory activities are based on supervisory strategies that are developed for each institution that are risk-based and focused on the more complex banking activities. -

Hsi 12.31.20

HSBC SECURITIES (USA) INC. Statement of Financial Condition December 31, 2020 2 HSBC Securities (USA) Inc. STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL CONDITION December 31, 2020 (in millions) Assets Cash................................................................................................................................................................... $ 285 Cash segregated under federal and other regulations ....................................................................................... 609 Financial instruments owned, at fair value (includes $9,072 pledged as collateral, which the counterparty has the right to sell or repledge)..................................................................................................................... 9,153 Securities purchased under agreements to resell (includes $4 at fair value)..................................................... 20,643 Receivable under securities borrowing arrangements....................................................................................... 11,758 Receivable from brokers, dealers, and clearing organizations.......................................................................... 4,154 Receivable from customers................................................................................................................................ 269 Other assets (include $13 at fair value)............................................................................................................. 295 Total assets.......................................................................................................................................................