Republic of the Union of Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Production Sharing Contract (Psc) in Myanmar's Upstream Oil & Gas Sector

PRODUCTION SHARING CONTRACT (PSC) IN MYANMAR’S UPSTREAM OIL & GAS SECTOR 28th March,2012 Htin Aung Director General Energy Planning Department 1 Contents Energy Policy Status of Myanmar Upstream Oil & Gas Sector Current & On going Projects Current Natural Gas Production and Export Status Current PSC Standard Terms & Conditions Role of MOGE in PSC 22 Energy Policy To maintain the Status of Energy Independence To promote wider use of New and Renewable Sources of Energy To promote Energy Efficiency and Conservation To promote Use of Alternative Fuels in household To Implement Effective Utilization of Discovered Crude Oil and Natural Gas Resources in the Interest of the Entire Nation including the Regions where the discovery was made To Promote more Private Participation 33 Energy Policy To Utilize Discovered Natural Gas Reserves for Domestic Consumption as Priority and to Produce Value Added Products from Surplus Natural Gas Reserves To Allow Free Distribution and Importation of HSD/MS/RON 92/LPG for Public Sector usage by Local Private Entrepreneurs To sell Petroleum Products with Floating Price in accordance with Existing International Market Price to be in line with Market Oriented Economic System To Utilize Alternative Fuels during the Period the Natural Gas could not be Supplied to Fulfill Domestic Requirement 4 4 Energy Policy To Save Energy through Effective Energy Management and to Minimize the Harmful Impact to the Environment To Eliminate the Energy Waste caused by User Carelessness and Inefficient Equipments Usage To Encourage for Energy Efficient Performance by involving of Private Sector 55 Status of Myanmar’s Upstream Oil & Gas Sector 66 Oil & Gas Bearing Areas of Myanmar SEDIMENTARY BASINS OIL AND GAS BEARING AREAS OF MYANMAR STATUS OF EXPLORATION 1. -

A History of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964)

University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Year A history of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964) Kyaw Zaw Win University of Wollongong Win, Kyaw Zaw, A history of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964), PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2008. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/106 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/106 A HISTORY OF THE BURMA SOCIALIST PARTY (1930-1964) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy From University of Wollongong By Kyaw Zaw Win (BA (Q), BA (Hons), MA) School of History and Politics, Faculty of Arts July 2008 Certification I, Kyaw Zaw Win, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Kyaw Zaw Win______________________ Kyaw Zaw Win 1 July 2008 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations and Glossary of Key Burmese Terms i-iii Acknowledgements iv-ix Abstract x Introduction xi-xxxiii Literature on the Subject Methodology Summary of Chapters Chapter One: The Emergence of the Burmese Nationalist Struggle (1900-1939) 01-35 1. Burmese Society under the Colonial System (1870-1939) 2. Patriotism, Nationalism and Socialism 3. Thakin Mya as National Leader 4. The Class Background of Burma’s Socialist Leadership 5. -

Economic and Engineering Development of Burma 1953

NOMIC AND ENGINEER! DEVELOPMENT OF BURMA PREPARED FOE TKl LENT OF THE UNION OF BURMA VOLUME AUGUST If53 KNAPPEN TiPPETTS ABBETT MCCARTHY _ ENGINEERS m ASSOCIATION WITH PIERCE itaJAGEMENT, INC. AND ROBERT R. NATHAN ASSOCIATES, INC, u ^^^^< ' o(t, fseco ECONOMIC AND ENGINEERING DEVELOPMENT OF BURMA KNAPPEN - TIPPETTS - ABBETT - MCCARTHY ENGINEERS (KNAPPEN TIPPETTS ABBETT ENGINEERING CO.) 62 WEST 47TH STREET ERNEST F. TIPPETTS PLEASE REPLY TO NEW YORK 36, N .Y. ROBERT W. ABBETT SOUTH EAST ASIA OFFICE P.O. Box 1484 GERALD T. MCCARTHY PLAZA 7-8001 PRO ME COURT WILLIAM Z. LIDICKER RANC300N. BURMA JAMES H. STRATTON SOUTH 556 & 572 CABLE ADDRESS : "KNAPENG RANGOON" August 7th, 1953 THE HONORABLE U WIN, Minister for National Planning and Religious Affairs, Prome Court, Prome Road, RANGOON, BURMA. DEAR SIR, The Consultants take pleasure in transmitting to you the accompanying "Comprehensive Report on the Economic and Engineering Development of Burma." It is the earnest hope of all who have contributed to the preparation of the Report that it will be a trustworthy guide to social and industrial progress that will endure and strengthen through the years to come. The Consultants desire to express their thanks and apprecia¬ tion for the honor and opportunity afforded them to participate in the bold, creative, and historical measures being set in motion by the Union of Burma to secure for her people the full enjoyment of their rich resources. Respectfully yours, General Manager COMPREHENSIVE REPORT ECONOMIC AND ENGINEERING DEVELOPMENT OF BURMA PREPARED FOR THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNION OF BURMA VOLUME I INTRODUCTION ECONOMICS AND ADMINISTRATION AGRICULTURE AND IRRIGATION TRANSPORTATION AUGUST 1953 KNAPPEN TIPPETTS ABBETT McCARTHY ENGINEERS IN ASSOCIATION WITH PIERCE MANAGEMENT, INC. -

Administrative Map

Myanmar Information Management Unit Myanmar Administrative Map 94°E 96°E 98°E 100°E India China Bhutan Bangladesh Along India Vietnam KACHIN Myanmar Dong Laos South China Sea Bay of Bengal / Passighat China Thailand Daporija Masheng SAGAING 28°N Andaman Sea Philippines Tezu 28°N Cambodia Sea of the Philippine Gulf of Thailand Bangladesh Pannandin !( Gongshan CHIN NAWNGMUN Sulu Sea Namsai Township SHAN MANDALAY Brunei Malaysia Nawngmun MAGWAY Laos Tinsukia !( Dibrugarh NAY PYI TAW India Ocean RAKHINE Singapore Digboi Lamadi KAYAH o Taipi Duidam (! !( Machanbaw BAGO Margherita Puta-O !( Bomdi La !( PaPannssaauunngg North Lakhimpur KHAUNGLANHPU Weixi Bay of Bengal Township Itanagar PUTA-O MACHANBAW Indonesia Township Township Thailand YAN GON KAY IN r Khaunglanhpu e !( AYE YARWADY MON v Khonsa i Nanyun R Timor Sea (! Gulf of Sibsagar a Martaban k Fugong H i l NANYUN a Township Don Hee M !( Jorhat Mon Andaman Sea !(Shin Bway Yang r Tezpur e TANAI v i TANINTHARYI NNaaggaa Township R Sumprabum !( a Golaghat k SSeellff--AAddmmiinniisstteerreedd ZZoonnee SUMPRABUM Township i H Gulf of a m Thailand Myanmar administrative Structure N Bejiang Mangaldai TSAWLAW LAHE !( Tanai Township Union Territory (1) Nawgong(nagaon) Township (! Lahe State (7) Mokokchung Tuensang Lanping Region (7) KACHIN INDIA !(Tsawlaw Zunheboto Hkamti INJANGYANG Hojai Htan Par Kway (! Township !( 26°N o(! 26°N Dimapur !( Chipwi CHIPWI Liuku r Township e Injangyang iv !( R HKAMTI in w Township d HPAKANT MYITKYINA Lumding n i Township Township Kohima Mehuri Ch Pang War !(Hpakant -

Memoirs of the Four-Foot Colonel the Cornell University Southeast Asia Program

__,, -�, / a ' ' ' '• ' ,,, '.' • • , •l' •• - '"' ,- "'Ji"' ' " ' ' - ' ·Iii! " ' -� ,.._ � ' m " � 'Iii, "SWI , � � ml ' ' • • ,t·P0;. "' '" . • ' i' • MEMOIRS OF THE FOUR-FOOT COLONEL THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the Department of Far Eastern Studies in 1950. It is a teaching and research program of interdisciplinary studies in the humanities, social sciences, and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the individual countries of the area: Brunei, Burma, Indonesia, Kampuchea, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the Program are carried on both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an undergraduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by specialists in Southeast Asian cultural history and present-day affairs and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Program sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on linguistic studies of the languages of the area. At the same time, indi vidual staff and students of the Program have done field research in every Southeast Asian country. A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at the end of this volume. Information on Program staff, fellowships, requirements for degrees, and current course offerings is obtainable from the Director, Southeast Asia Program, 120 Uris Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853. ii MEMOIRS OF THE FOUR-FOOT COLONEL by Gen. Smith Dun First Commander-in-Chief of Independent _sBurma's Armed Forces Data Paper: Number 113 Southeast Asia Program Department of Asian Studies Cornell University, Ithaca, New York • May 1980 ••• Ill Editorial Board Benedict Anderson George Kahin Stanley O'Connor Keith Taylor Oliver Wolters Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications 640 Stewart Avenue, Ithaca, NY 14850-3857 Data Paper Series No. -

Opportunities for Cooperation in Myanmar Petroleum Energy Sector

Opportunities for Cooperation in Myanmar Petroleum Energy Sector Aung Kyaw Htoo Assistant Director Energy Planning Department Ministry of Energy Yangon, 20-21 June 2012 1 Content 1. Ministry of Energy 2. Petroleum Oil & Gas Sector 3. Petrochemical Industry Sector 4. Petroleum Products Sector 5. Opportunities 6. Conclusion 2 (Ministry of Energy) Organizations and Respective Responsibilities Myanma Energy Myanma Oil Myanma Petroleum Planning and Gas Petrochemical Products Department Enterprise Enterprise Enterprise (EPD) (MOGE) (MPE) (MPPE) • Technical Arm • Exploration • Refineries & Process • Marketing • Coordination • Drilling • Fertilizer Plants • Distribution • Management • Production •Methanol Plant • Regulation • Onland Oil and Gas • CO2 and LPG Plants Pipeline Network • Waxing & Tar • CNG 3 Institutional Framework Petroleum MINISTRY OF ENERGY MINISTRY OF ELECTRIC POWER (I) Electricity MINISTRY OF ELECTRIC POWER (II) Coal MINISTRY OF MINES MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION Biomass and AND FORESTRY Fuelwood MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND IRRIGATION Renewable MINISTRY OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY Energy MINISTRY OF INDUSTRY * Ministry of Energy is a Focal Point of the Myanmar Energy Sector Cooperation in the Region 4 Petroleum Oil and Gas Sector 5 Exploration and Development of Petroleum Petroliferous Basin SEDIMENTARY BASINS STATUS OF EXPLORATION 1. Rakhine Coastal (Onshore) 2. Hukaung A. Thoroughly Explored Basins 3. Chindw in 1. Central Myanmar 4. Shw ebo-Monywa 2. Pyay Embayment 5. Central Myanmar 3. Ayeyarw ady Delta 6. Pyay Embayment (Only Part of the Basin) 7. Ayeyarw ady Delta 8. Bago Yoma Basin B. Explored to Some Extent 9. Sittaung Valley 1. Chindw in 10. Mepale 2. Rakhine Coastal 11. Maw lamyine 12. Namyau C. Very Little Explored 13. Hsipaw -Lashio 1. Hukaung 14. -

Detailed Poverty and Social Impact Analysis

Climate-Friendly Agribusiness Value Chains Sector Project (RRP MYA 48409-003) Detailed Poverty and Social Impact Analysis August 2018 MYA: Climate-Friendly Agribusiness Value Chains Sector Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 16 August 2018) Currency unit – Myanmar Kyat (MMK) MMK1.00 = $0.000666 $1.00 = MK1,501.00 ABBREVIATIONS ADB − Asian Development Bank ASEAN − Association of Southeast Asian Nations CDZ − central dry zone CEC − Commodity Exchange Center DOA − Department of Agriculture GDP − gross domestic product IHLCS − Integrated Household Living Conditions Surveys LIFT − Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund MOALI − Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation NGO − nongovernment organization PPP − purchase power parity NOTE In this report, “$” refers to United States dollars. I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. The proposed Climate-Friendly Agribusiness Value Chains Sector Project will invest in pro-poor and inclusive agricultural value chains in three countries of the Greater Mekong Subregion – the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (Myanmar), the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), and the Kingdom of Cambodia. This report presents the findings of the socio- economic, poverty and gender assessment undertaken during the preparation and design of the Climate-Friendly Agribusiness Value Chains Sector Project in Myanmar. 2. The project preparatory technical assistance social development consultant team carried out participatory socioeconomic assessments in selected target areas to better understand the social, poverty and gender aspects of the target populations in subproject areas. 3. Findings showed that the local farming populations in subproject areas 1 and 2 are largely homogeneous although there are more casual workers and underemployed households in subproject area 1. 4. The target populations needs and demands were assessed in relation to the proposed subprojects. -

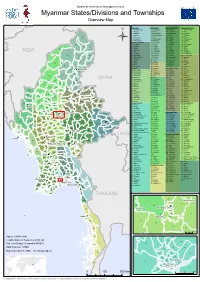

Myanmar States/Divisions and Townships Overview Map

Myanmar Information Management Unit Myanmar States/Divisions and Townships Overview Map Kayin State Kachin State Shan (South) State Bago West Division 1 Thandaunggyi 84 Nawngmun 165 Ywangan 246 Paukkhaung 2 Hpapun 85 Puta-O 166 Lawksawk 247 Pyay 3 Hlaingbwe 86 Machanbaw 167 Mongkaung 248 Padaung 4 Hpa-An 87 Khaunglanhpu 168 Kyethi 249 Paungde 84 5 Myawaddy 88 Tanai 169 Monghsu 250 Thegon 6 Kawkareik 89 Sumprabum 170 Pindaya 251 Shwedaung 7 Kyainseikgyi 90 Tsawlaw 171 Kalaw 252 Nattalin Ü Bago East Division 91 Injangyang 172 Taunggyi 253 Zigon 85 8 Yedashe 92 Chipwi 173 Hopong 254 Gyobingauk 86 87 9 Taungoo 93 Hpakan 174 Loilen 255 Okpho 118 10 Oktwin 94 Myitkyina 175 Laihka 256 Monyo 11 Htantabin 95 Mogaung 176 Nansang 257 Minhla INDIA 12 Phyu 96 Waingmaw 177 Kunhing 258 Letpadan 13 Kyaukkyi 97 Mohnyin 178 Mongnai 259 Thayarwady 119 88 89 90 14 Kyauktaga 98 Momauk 179 Pinlaung Magway Division 15 Nyaunglebin 99 Shwegu 180 Nyaungshwe 260 Gangaw 91 16 Shwegyin 100 Bhamo 181 Hsihseng 261 Tilin 17 Daik-U 101 Mansi 182 Mawkmai 262 Myaing 120 92 18 Bago Kayah State 183 Langkho 263 Yesagyo 93 19 Waw 102 Loikaw 184 Mongpan 264 Pauk 20 Thanatpin 103 Shadaw 185 Pekon 265 Pakokku Shan (North) State 121 ! 21 Kawa 104 Demoso 266 Saw 95 Myitkyina Rakhine State 105 Hpruso 186 Mabein 267 Seikphyu 96 22 Maungdaw 106 Bawlakhe 187 Mongmit 268 Chauk 94 23 Buthidaung 107 Hpasawng 188 Manton 269 Salin 97 122 24 Kyauktaw 108 Mese 189 Namhkan 270 Sidoktaya 25 Mrauk-U Chin State 190 Muse 271 Natmauk BANGLADESH CHINA 26 Ponnagyun 109 Tonzang 191 Kutkai 272 Yenangyaung -

Relationship Between Climate Change Impact, Migration and Socioeconomic Development

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLI-B4, 2016 XXIII ISPRS Congress, 12–19 July 2016, Prague, Czech Republic RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACT, MIGRATION AND SOCIOECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Kyaw Sann Oo * MGRP, Myanmar Peace Center, 11 Shwe Li Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon, Myanmar - [email protected] ISPRS – UN-GGIM Forum KEY WORDS: Migration, rural, agriculture, urban, climate change ABSTRACT: Geospatial data are available in raster and vector formats and some of them are available in open data form. The technique and tools to handle those data are also available in open source. Though it is free of charge, the knowledge to utilize those data is limited to non-educated in the specific field. The data and technology should be promoted to those levels to utilize in required fields with priceless in developing countries. Before utilize open data, which are required to verify with local knowledge to become usable information for the local people as priceless data resources. Developing country, which economic is based in agriculture, required more information about precise weather data and weather variation by the climate change impact for their socioeconomic development. This study found that rural to urban migration occurs in the developing countries such agriculture based country likes Myanmar when the agriculture economic are affected by unpredictable impact by the climate change. The knowledge sharing using open data resources to non-educated local people is one of the curable solutions for the agriculture economy development in the country. Moreover, the study will find ways to reduce the rural to urban migration. -

Village Tract of Bago Region (West)

!. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !.!. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. Myanmar Information Management Unit Village Tract of Bago Region (West) !. !. 95° E 96° E Aunglan !. Mindon !. !. Thayet / !. !. MAGWAY ! ! ! ! ! REGION ! !. Lay! Thar Taung Thit Sein Pin !. ! ! Gyi ! ! ! ! ! !. ! ! Thit Poke ! ! ! ! Kan Kyin ! Myauk Forest Shwe ! ! ! ! Laung ! Forest Kywe Ka Dee Doke ! ! ! Lay San ! ! ! ! ! ! Nwar Myaw Sin Gaung Ma Gyi ! ! Bant ! Khon Kyu Wut Bway Taung !. Forest ! ! ! !. ! !. ! ! ! Htone Taung ! Kan Kyi Kone ! ! ! War Yon Seik Forest ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Hlwa Zin Kanma ! !. ! ! ! War !Yon ! ! ! !. ! ! ! ! ! Pin Lel ! ! Taung ! Nyaung ! ! Ah Yar Taw Shwe Pauk Nwe Pin Thar ! ! Ah Lo Htan Ta Pin Laung ! ! ! ! Chon ! ! ! Taw Ya ! ! Kyaw Thar ! ! ! 19° N 19° N 19° ! ! Kan Kyo ! Kwin Gyi ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! -

Economic and Engineering Development of Burma, 1953, Volume 2

MANUFACTURING 687 Forest Raw Materials Principal Manufactured Products Metallic Mineral Note: Tree products—e.g. coconut, rubber which are Raw Material (contd.) Principal Manufactured Products generally grown on an organized plantation basis are listed under Bismuth (found in small quan¬ As elemental bismuth, used for Agricultural Raw Materials. tity in wolfram-bearing allu¬ medicines; cosmetics; manufacture vial deposits of Tavoy and of thin-walled tubing; seals for Bamboo Paper; rafting material; building Mergui areas; also in tlie tin- nitriding furnaces; electroforming; framing material (untreated and wolfram lode at Kanbauk) additive to aluminum alloys; impregnated); building sidings; additive to stainless, manganese, furniture; floor mats, etc. and carbon steels; fuze alloys and Camphor Drugs. other low melting point alloys; Cane Rattan work; baskets; mats; rectifier coatings; tin-saving sol¬ cordage substitute. ders; bearings. As bismuth sub- Cinnamon Spices. carbonate, used for ceramic glazes Cutch Tanning agents; dyes. and artificial horn products; as Hardwoods, not elsewhere Squares, sawn untreated timber basic bismuth chloride, used for classified and lumber; impregnated timber cosmetics, paint pigments and and lumber; lumber products; artificial pearls; as basic bismuth chipboard (from sawmill wastes); nitrate, used for bismuth fluxes for plywood; tea chests; railway enamels and cosmetics. sleepers and keys; charcoal; fire¬ wood. Gurjan has most of the Chromium (several occur¬ Heat and corrosion resisting alloy characteristics of teak. rences of chromite reported in steels; nickel chrome resistance Lac Shellac; sealing wax; phonograph Arakan Yomas, and several wire; tanning compounds; dyeing records; varnishes. others in Kamaing subdivision mordants; oxygen absorber in gas Leaves, miscellaneous Wrapping materials. of Myitkyina district; no analysis; camouflage pigments; Mangrove Tannin; firewood. -

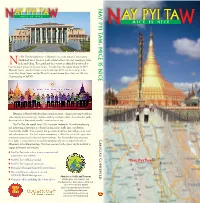

NPT Booklet Cover 6Feb Combined

AY PYI TA PYI TAW NAY N M I C E I S N I C E W AY PYI TA N M I C E I S N I C E W , MICE IS NICE ay Pyi Taw the capital city of Myanmar, sits at the centre of the country which itself sits at the cross roads of Asia between two vast emerging powers, India and China. The capital and the country are admirably positioned to becomeN major players in the near future. Already since the regime change in 2010 Myanmar has re-staked its claim on the world stage. 2013 saw the hosting of the South East Asian Games and the World Economic Forum (East Asia) and 2014 the Chairmanship of ASEAN. Myanmar is blessed with abundant natural resources, a large and young workforce, wide-ranging investment opportunities, and a government that is determined to guide the country to a democratic, market-orientated economy. Nay Pyi Taw, the capital since 2005, has green credentials. It combines pleasing and interesting architecture, good landscaping and no traffic jams or pollution. Seated in the middle of the country, this government city is a hub with good air, road and rail connections. For the business community it offers first rate hotels, up to date convention centres and a fine new sports stadium. For the traveller there are many Caroline Courtauld Caroline local sights to enjoy and it is an excellent jumping-off point to explore the rest of Myanmar’s rich cultural heritage. For these reasons it is the ‘green’ city from which to engage in business and tourism.