Achieving a Demographic Dividend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capturing the Demographic Dividend in Pakistan

CAPTURING THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND IN PAKISTAN ZEBA A. SATHAR RABBI ROYAN JOHN BONGAARTS EDITORS WITH A FOREWORD BY DAVID E. BLOOM The Population Council confronts critical health and development issues—from stopping the spread of HIV to improving reproductive health and ensuring that young people lead full and productive lives. Through biomedical, social science, and public health research in 50 countries, we work with our partners to deliver solutions that lead to more effective policies, programs, and technologies that improve lives around the world. Established in 1952 and headquartered in New York, the Council is a nongovernmental, nonprofit organization governed by an international board of trustees. © 2013 The Population Council, Inc. Population Council One Dag Hammarskjold Plaza New York, NY 10017 USA Population Council House No. 7, Street No. 62 Section F-6/3 Islamabad, Pakistan http://www.popcouncil.org The United Nations Population Fund is an international development agency that promotes the right of every woman, man, and child to enjoy a life of health and equal opportunity. UNFPA supports countries in using population data for policies and programmes to reduce poverty and to ensure that every pregnancy is wanted, every birth is safe, every young person is free of HIV and AIDS, and every girl and woman is treated with dignity and respect. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Capturing the demographic dividend in Pakistan / Zeba Sathar, Rabbi Royan, John Bongaarts, editors. -- First edition. pages ; cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-87834-129-0 (alkaline paper) 1. Pakistan--Population--Economic aspects. 2. Demographic transition--Economic aspects--Pakistan. -

Creating and Capitalizing on the Demographic Dividend for Africa Cover Credits: Mariama Zachary and Akua Azaiz Tend to Cocoa Beans on a Drying Table

Creating and Capitalizing on the Demographic Dividend for Africa Cover Credits: Mariama Zachary and Akua Azaiz tend to cocoa beans on a drying table. Cocoa beans are an important cash crop for the farmers in Sawuah, many of whom use the profits to send their children to school. When small farmers are able to increase their productivity, it improves not only their well-being, but the living standards of their family and communities for the long term. (Sawuah, Ghana, 2011) © Photo Courtesy of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation 2 CREATING AND CAPITALIZING ON THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND FOR AFRICA ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This issues paper on the Demographic Dividend, jointly sponsored by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) and the African Union Commission (AUC), was prepared under the leadership of Thokozile Ruzvidzo, Director of the African Centre for Gender and Social Development, with the active involvement of Olawale Maiyegun, Direc- tor of the AUC Department of Social Affairs. Directions for and preparation of the paper benefited from inputs provided by members of the Demographic Dividend Side Event Steering Committee affiliated with the following organizations: Sahlu Haile and Yemeser- ach Belayneh (David and Lucile Packard Foundation); Benoit Kalasa and Serge Bounda (UNFPA); Jotham Musinguzi (Partners for Population and Development, Africa Regional Office); Olu Ajakaiye (African Centre for Shared Development Capacity Building); Euge- nia Amporfu (African Health Economic Association); Latif Dramani (Université de Thiès); Cheikh Mbacke (William and Flora Hewlett Foundation); Eliya Zulu (African Institute for Development Policy); Agnes Soucat (African Development Bank); Scott Radloff (US Agen- cy for International Development). In addition the paper relied on technical research material from David Bloom and David Canning at Harvard University, Andrew Mason at the University of Hawaii, Ronald Lee at the University of California at Berkeley and the Popu- lation Reference Bureau. -

Demography and Economic Growth: a Policy-‐Dependent Relationship

Demography and Economic Growth: A policy-dependent relationship Vincent Barras and Hans Groth World Demographic & Ageing Forum (WDA Forum), St. Gallen, Switzerland Demographic dynamics, together with other megatrends such as globalization, urbanization, industrialization, and the rise of technology, are shaping the future of our societies and economies. Unfortunately, descriptions of megatrends often lack the required granularity to provide actionable insights to policy makers and business planners. This article bridges this gap by highlighting how demographic dynamics influence economic growth. It also puts forward action levers to improve countries’ demographic fitness and economic competiveness. In a first stage, we introduce the field of demography and the fundamental concepts of demographic transition and demographic dividend. Further, we summarize the impact of demography on economic growth to establish the hypothesis that growth-inducing policies are the key drivers of economic development, whereas population size and structure play an enabling secondary role. We then analyze how population, social, and economic policies can help manage two main challenges posed by demographic dynamics globally. On the one hand, the more developed countries need to find a way of maintaining wealth and welfare and of prospering with a shrinking and ageing workforce. On the other hand, the less developed countries need to build societies that offer employment and opportunities to their young in order to avoid social unrest. In our conclusion, we explain why and how international cooperation is key to address emerging global demographic imbalances. We also highlight that when it comes to managing demographic transitions at a national and transnational level, failure is not an option. -

Harnessing the Demographic Dividend in Uganda an Assessment of the Impact of Multisectoral Approaches

HARNESSING THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND IN UGANDA AN ASSESSMENT OF THE IMPACT OF MULTISECTORAL APPROACHES Economic Policy Research THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Institute AN ASSESSMENT OF THE IMPACT OF MULTISECTORAL APPROACHES 1 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA NATIONAL POPULATION COUNCIL (NPC) Acknowledgements Harnessing the demographic dividend in Uganda demands targeted efforts to optimize the relationship between economic and population growth. This publication provides unique insight into the complex interplay between various economic and social forces, as well as public investment decisions through which Government can best leverage unprecedented economic opportunities brought about by the current demographic transition. The research and drafting of this report was led by the Economic Policy Research Institute (EPRI), in close collaboration with the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, the National Planning Authority, the National Population Council, the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBoS) and UNICEF Uganda. Frances Ellery provided editorial inputs and Rachel Kanyana designed this publication and its associated advocacy materials. HARNESSING THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND IN UGANDA An Assessment of the Impact of Multisectoral Approaches Economic Policy Research THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Institute THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA NATIONAL POPULATION COUNCIL (NPC) Foreword With over half its population under the age of 18, Uganda has one of the youngest populations in the world. This is only expected to increase over the coming decades as the number of children, adoles- cents and youth in Uganda is forecasted to rise from 27.5 million in 2015 to 75.9 million in 2080. Based on these population dynamics, Uganda is uniquely positioned to harness the economic and social bene- fits of a young and growing dynamic population. -

Demographic Dividend Potential for Africa Demographic Dividend

Demographic Dividend Potential For Africa Some Findings from Two WBG Reports Washington, April, 2015 1000000 2000000 3000000 4000000 Source: adapted toWorldBank regionsusing data fromUnitedNa 0 2010 South Asia Latin America& Caribbean East Asia&Pacific 2013 2016 2019 2022 2025 2028 2031 Scenario Medium Fertility 2034 Population Projections 2037 tions, Department of EconomicandPopulation tions, Department Social Di Affairs, 2040 2043 2046 2049 2052 2055 2058 Sub-Saharan Africa Middle East&North Africa Europe &Central Asia 2061 2064 2067 2070 2073 vision (2013). 2076 2079 2082 2085 2088 2091 2094 2097 2100 Dividend or Disaster? Highest fertility rates in the world are associated with: • High maternal and child mortality • Low women’s empowerment • Low investment in education • High dependency ratios • Youth employment challenges Background papers (regional report) 1 Literature Review Demographics 12 Aging and in Africa 2 Population polices in Africa 13 Source economic growth in Africa 3 Literature Review Demographic Dividend 14 Savings in Africa 4 Social determinants in Africa 15 Model of the Economic Effects of Fertility Change 5 Proximate determinants of Africa 16 Case Study – Pakistan and Bangladesh 6 Supply Side of Family Planning 17 Case Study – Nigeria and Kenya 7 18 Case Study – Ethiopia and Ghana The Demographic Transition and Urbanization 8 The Effect of Demographic Transition on Child 19 Case Study - DRC Health 9 The Effect of Demographic Transition on 20 Case Study - Brazil Education 4 10 The Youth Bulge and Labor Markets 11 Fertility and Female Labor Force Participation Africa’s rise: Twenty years of sustained economic growth have established that Africa can find its own path to successful development. -

THE CHALLENGE of ATTAINING the DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND BOX 2 Thailand: Reaping the Dividends of a Demographic Transition

POPULATION REFERENCE Policy Brief BUREAU SEPTEMBER 2012 BY JAMES GRIBBLE THE CHALLENGE OF ATTAINING AND JASON BREMNER THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND Policymakers, researchers, and other stakeholders optimistically discuss the demographic dividend. Fertility has declined Most view the benefits as imminent and within grasp BOX 1 in most countries in (see Box 1). However, many of the least developed sub-Saharan Africa, and countries will be challenged to achieve this economic Demographic Dividend women in the region today have on average 5.1 benefit without substantially lowering birth and child The demographic dividend is the accelerated eco- children, compared to 6.7 death rates—a process referred to as the “demo- children in 1970. graphic transition.” While child survival has greatly nomic growth that may result from a decline in a improved in developing countries, birth rates remain country’s mortality and fertility and the subsequent change in the age structure of the population. high in many of them. To reach their full economic With fewer births each year, a country’s young potential, these countries must act today to increase dependent population grows smaller in relation to their commitment to and investment in voluntary the working-age population. With fewer people to family planning. support, a country has a window of opportunity for rapid economic growth if the right social and eco- This policy brief explains the connection between the nomic policies developed and investments made. 40% demographic dividend and investments in voluntary The percentage of the family planning; highlights Africa’s particular chal- population in the world’s lenge in achieving a demographic dividend and the least developed countries under age 15. -

Report. the Demographic Dividend: an Opportunity for Ethiopia's

ETHIOPIAN THE DEMOGRAPHIC ECONOMICS DIVIDEND: ASSOCIATION AN OPPORTUNITY FOR ETHIOPIA’S OCTOBER 2015 TRANSFORMATION www.prb.org ETHIOPIAN ECONOMICS ASSOCIATION Acknowledgments This report benefited from the analysis and thoughtful review and comments of many individuals. Assefa Adamassie and Seid Nuru of the Ethiopian Economic Association (EEA) were responsible for the overview of Ethiopia’s economic situation, programs and policies, and analysis of changes as relevant to the demographic dividend. John F. May of the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) provided the demographic analysis alongside the review of evolving public health efforts in Ethiopia. Shelley Megquier of PRB led the overall editing and review process for the report, contributing to the demographic dividend framework guiding the effort. Scott Moreland of Palladium provided and interpreted results from the DemDiv simulation tool. Thanks are also due to the following individuals for their helpful comments and contributions: Marlene Lee, program director, Academic Research and Relations, PRB; Peter Goldstein, vice president, Communications and Marketing, PRB; Heidi Worley, senior writer/editor, PRB; Jean-Pierre Guengant, director emeritus of Research, Research Unit University of Paris-I, Panthéon-Sorbonne and Research Institute for Development (IRD), Paris; and Sahlu Haile, senior scholar at the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. This publication was made possible by the generous support of the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. The contents are the responsibility of EEA and PRB, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. Suggested citation: Admassie, Assefa, Seid Nuru Ali, John F. May, Shelley Megquier, and Scott Moreland. 2015. “The Demographic Dividend: An Opportunity for Ethiopia’s Transformation,” Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau and Ethiopian Economics Association. -

Demographic Dividend

September 2004 Understanding the Demographic Dividend By John Ross A fresh reason for attending to fertility dynamics has emerged—the “demographic dividend.” As fertility rates fall during the demographic transition, if countries act wisely before and during the transition, a special window opens up for faster economic growth and human development. WHAT IS THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND? Simply stated, the demographic dividend occurs when a falling birth rate changes the age distribution,1 so that fewer investments are needed to meet the needs of the youngest age groups and resources are released for investment in economic development and family welfare. That is, a falling birth rate makes for a smaller population at young, dependent ages and for relatively more people in the adult age groups—who comprise the productive labor force. It improves the ratio of productive workers to child dependents in the population. That makes for faster economic growth and fewer burdens on families. The Republic of Korea serves as an example: as its birth rate fell in the mid-1960s, elementary school enrolments declined and funds previously allocated for elementary education were used to improve the quality of education at higher levels. Population pyramids for Korea and Nigeria in 2000 (presented in Figures 1 and 2) demonstrate the different population dynamics that are at work. In Korea the bulge is at the working ages whereas in Nigeria the young dependent ages stand out, with all the burdens that they represent in that poor country. 1 The demographic module in the POLICY Project’s SPECTRUM Suite of Models can be used to project the changing age structure of the population and indicate the timing and magnitude of the potential demographic dividend. -

Population, Development, and Policy

Population Council Knowledge Commons Poverty, Gender, and Youth Social and Behavioral Science Research (SBSR) 9-23-2020 Population, development, and policy John Bongaarts Population Council Michele Gragnolati S. Amer Ahmed Jamaica Corker Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-pgy Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Bongaarts, John, Michele Gragnolati, S. Amer Ahmed, and Jamaica Corker. 2020. "Population, development, and policy." New York: Population Council. This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Population Council. POPULATION, DEVELOPMENT, AND POLICY John Bongaarts, Population Council Michele Gragnolati, World Bank S. Amer Ahmed, World Bank Jamaica Corker, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation The Population Council confronts critical health and development issues—from stopping the spread of HIV to improving reproductive health and ensuring that young people lead full and productive lives. Through biomedical, social science, and public health research in 50 countries, we work with our partners to deliver solutions that lead to more effective policies, programs, and technologies that improve lives around the world. Established in 1952 and headquartered in New York, the Council is a nongovernmental, nonprofit organization governed by an international board of trustees. Population Council 1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza New York, NY 10017 USA Tel: +1 212 339 0500 Fax: +1 212 755 6052 email: [email protected] popcouncil.org John Bongaarts is a Distinguished Scholar, Population Council, New York. Email: [email protected]. Michele Gragnolati is Manager for Strategy, Health, Nutrition & Population, World Bank. -

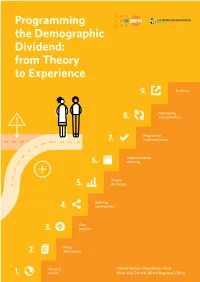

Programming the Demographic Dividend: from Theory to Experience

Programming the Demographic Dividend: from Theory to Experience 9. Scale-up Monitoring 8. and evaluation ! Programme 7. implementation Implementation 6. planning Theory 5. of change Building 4. partnerships Gap 3. analysis Policy 2. declaration Country United Nations Population Fund 1. profile West and Central Africa Regional Office Programming the Demographic Dividend: from theory to experience UNFPA Regional Office for West and Central Africa 2 Table of content Abbreviations and acronyms 7 Foreword 8 Executive summary 10 Introduction 12 1. Three Phases and Nine Steps for Action 13 2. The Concept of the Demographic Dividend: Some Results in Africa and the World 14 3. Conclusion 25 Step I. Country profil 26 1.1. The Need to Establish a Profile for each Country 26 1.2. The Choice of the Model for Establishing the Country Profiles 26 1.3. Choice of Variables and Indicators 32 1.4. Sources of Information 34 1.5. Analysis of the Country Profile 34 1.6. Conclusion 35 Step II. Policy declaration 36 2.1. The Action Framework 36 2.2. Advanced Tips – Real Advantages of a PDHDD 40 2.3. Progress on the Road to a PDHDD – Country Mapping in some West and Central African Countries 44 2.4. Conclusion 48 Step III. Gap analysis 50 3.1. What is Gap Analysis? 50 3.2. Identification and Quantification of the Gaps 51 3.3. Use of the gap analysis in the overall evaluation strategy 53 3.4. Conclusion 54 Step IV. Building partnerships 56 4.1. Partnership-building Methodology 56 4.2. Additional Tips for Building Partnerships 60 4.3. -

Population Dynamics and the Demographic Dividend Potential of Eastern and Southern Africa: a Primer

Population Dynamics and the Demographic Dividend Potential of Eastern and Southern Africa: A Primer November 2019 UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office Social Policy Working Paper Population Dynamics and the Demographic Dividend Potential of Eastern and Southern Africa: A Primer © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) United Nations Complex, Gigiri, PO Box 44145 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya November 2019 This is a working document. It has been prepared to facilitate the exchange of knowledge and to stimulate discussion. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of UNICEF or the United Nations. The text has not been edited to official publication standards, and UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this document do not imply an opinion on the legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. Acknowledgements This working paper was written by Matthew Cummins (Social Policy Regional Adviser, UNICEF ESARO). The author would like to thank Debora Camaione (Public Finance Fellow, UNICEF ESARO) for the outstanding research support and assistance and also for leading the development of the accompanying Africa Population Dynamics Tool. The author is also grateful to the following persons for their comments on earlier drafts: Bo Viktor Nylund (Deputy Regional Director, UNICEF ESARO), Bob Muchabaiwa (Public Finance Specialist, UNICEF ESARO) and Natalie Fol (Regional Adviser Communication for Development, UNICEF ESARO). Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 2. The demographic transition and population boom .............................................................. -

The Demographic Dividend: a New Perspective On

R The Demographic Dividend A New Perspective on the Economic Consequences of Population Change David E. Bloom David Canning Jaypee Sevilla Supported by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation David and Lucile Packard Foundation Rockefeller Foundation United Nations Population Fund POPULATION MATTERS A RAND Program of Policy-Relevant Research Communication The research described in this report was supported by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the United Nations Population Fund. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bloom, David E. The demographic dividend : a new perspective on the economic consequences of population change / David E. Bloom, David Canning, Jaypee Sevilla. p. cm. “MR-1274.” ISBN 0-8330-2926-6 1. Demographic transition. 2. Age distribution (Demography) 3. Population. 4. Fertility, Human. 5. Economic development. 6. Demographic transition— Developing countries. I. Canning, David. II. Sevilla, Jaypee. III.Title. HB887 .B58 2002 304.6'2—dc21 2002024818 RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. © Copyright 2003 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from RAND. Published 2003 by RAND 1700 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 1200 South Hayes Street, Arlington, VA 22202-5050 201 North Craig Street, Suite 202, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-1516 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org/ To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Email: [email protected] PREFACE How does population growth affect economic development? Economists, demographers, and policymakers have debated this question for decades.