Public Art: Linking Form, Function and Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Art Implementation Plan

City of Alexandria Office of the Arts & the Alexandria Commission for the Arts An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy Submitted by Todd W. Bressi / Urban Design • Place Planning • Public Art Meridith C. McKinley / Via Partnership Elisabeth Lardner / Lardner/Klein Landscape Architecture Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Vision, Mission, Goals 3.0 Creative Directions Time and Place Neighborhood Identity Urban and Natural Systems 4.0 Project Development CIP-related projects Public Art in Planning and Development Special Initiatives 5.0 Implementation: Policies and Plans Public Art Policy Public Art Implementation Plan Annual Workplan Public Art Project Plans Conservation Plan 6.0 Implementation: Processes How the City Commissions Public Art Artist Identification and Selection Processes Public Art in Private Development Public Art in Planning Processes Donations and Memorial Artworks Community Engagement Evaluation 7.0 Roles and Responsibilities Office of the Arts Commission for the Arts Public Art Workplan Task Force Public Art Project Task Force Art in Private Development Task Force City Council 8.0 Administration Staffing Funding Recruiting and Appointing Task Force Members Conservation and Inventory An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 2 Appendices A1 Summary Chart of Public Art Planning and Project Development Process A2 Summary Chart of Public Art in Private Development Process A3 Public Art Policy A4 Survey Findings and Analysis An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 3 1.0 Introduction The City of Alexandria’s Public Art Policy, approved by the City Council in October 2012, was a milestone for public art in Alexandria. That policy, for the first time, established a framework for both the City and private developers to fund new public art projects. -

Public Art Toolkit

Aylesbury Vale Public Art Toolkit Who is this toolkit for? This toolkit can be used by anyone involved with making public art projects happen, however it has been developed to be specifically relevant to people commissioning art within a local authority context. What is public art? Public art has long been a feature of the public spaces across our towns and cities, with sculptures, paintings and murals often recalling historical characters or commemorating important events. Today, public art and artists are increasingly being placed at the centre of regeneration schemes as developers and local authorities recognise the benefits of integrating artworks into such programmes. Public art can include a variety of artistic approaches whereby artists or craftspeople work within the public realm in urban, rural or natural environments. Good public art seeks to integrate the creative skills of artists into the processes that shape the environments we live in. I see what you mean (2008), Lawrence Argent, University of Denver, USA For the Gentle Wind Doth Move Silently, Invisibly, (2006), Brian Tolle, Clevland, USA Spiral, Rick Kirby, (2004), South Woodham Ferres, Essex Animikii - Flies the Thunder, Anne Allardyce, (1992), Thunder Bay, Canada Types of Public Art approaches When thinking about future public art projects it is important to consider the full range of artistic approaches that could be used in a particular site, public art can be permanent or temporary; the following categories summarise popular approaches to public art. Sculpture Sculptural works are not solely about creating a precious piece of art but creating a piece which extends the sculpture into the wider landscape linking it with the environment and focussing attention on what is already there. -

A Finding Aid to the EC (Eugene) Goossen Papers, Circa 1935

A Finding Aid to the E.C. (Eugene) Goossen Papers, circa 1935-2004, in the Archives of American Art Sarah Mundy 2020/01/22 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Biographical Materials, 1945-2004........................................................... 4 Series 2: Correspondence, 1930s-1990s................................................................. 5 Series 3: Artist Files, circa 1947-1997..................................................................... 7 Series 4: Writing Projects and Notes, circa 1940-circa -

GREEN PAPER Page 1

AMERICANS FOR THE ARTS PUBLIC ART NETWORK COUNCIL: GREEN PAPER page 1 Why Public Art Matters Cities gain value through public art – cultural, social, and economic value. Public art is a distinguishing part of our public history and our evolving culture. It reflects and reveals our society, adds meaning to our cities and uniqueness to our communities. Public art humanizes the built environment and invigorates public spaces. It provides an intersection between past, present and future, between disciplines, and between ideas. Public art is freely accessible. Cultural Value and Community Identity American cities and towns aspire to be places where people want to live and want to visit. Having a particular community identity, especially in terms of what our towns look like, is becoming even more important in a world where everyplace tends to looks like everyplace else. Places with strong public art expressions break the trend of blandness and sameness, and give communities a stronger sense of place and identity. When we think about memorable places, we think about their icons – consider the St. Louis Arch, the totem poles of Vancouver, the heads at Easter Island. All of these were the work of creative people who captured the spirit and atmosphere of their cultural milieu. Absent public art, we would be absent our human identities. The Artist as Contributor to Cultural Value Public art brings artists and their creative vision into the civic decision making process. In addition the aesthetic benefits of having works of art in public places, artists can make valuable contributions when they are included in the mix of planners, engineers, designers, elected officials, and community stakeholders who are involved in planning public spaces and amenities. -

What Is Public Art?

POLICIES & PROCEDURES MANUAL Updated: February 2015 Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 4 What is Public Art? ................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 CITY-FUNDED PUBLIC ART ............................................................................................................... 5 Summary of the Process .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Funding Policies ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Funding Procedures ................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Public Art Manager’s Role ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Generating Ideas for Public Art in Capital Projects............................................................................................................................. 8 Methods of Selecting Public Art .......................................................................................................................................................... -

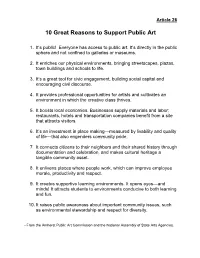

10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art

Article 26 10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art 1. It’s public! Everyone has access to public art. It’s directly in the public sphere and not confined to galleries or museums. 2. It enriches our physical environments, bringing streetscapes, plazas, town buildings and schools to life. 3. It’s a great tool for civic engagement, building social capital and encouraging civil discourse. 4. It provides professional opportunities for artists and cultivates an environment in which the creative class thrives. 5. It boosts local economies. Businesses supply materials and labor; restaurants, hotels and transportation companies benefit from a site that attracts visitors. 6. It’s an investment in place making—measured by livability and quality of life—that also engenders community pride. 7. It connects citizens to their neighbors and their shared history through documentation and celebration, and makes cultural heritage a tangible community asset. 8. It enlivens places where people work, which can improve employee morale, productivity and respect. 9. It creates supportive learning environments. It opens eyes—and minds! It attracts students to environments conducive to both learning and fun. 10. It raises public awareness about important community issues, such as environmental stewardship and respect for diversity. --From the Amherst Public Art Commission and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The Amherst Public Art Commission Why Public Art for Amherst? Public art adds enormous value to the cultural, aesthetic and economic vitality of a community. It is now a well-accepted principle of urban design that public art contributes to a community’s identity, fosters community pride and a sense of belonging, and enhances the quality of life for its residents and visitors. -

Eco-Art and Design Against the Anthropocene

sustainability Article Making the Invisible Visible: Eco-Art and Design against the Anthropocene Carmela Cucuzzella Design and Computation Arts, Concordia University, Montreal, QC H3G 1M8, Canada; [email protected] Abstract: This paper examines a series of art and design installations in the public realm that aim to raise awareness or activate change regarding pressing ecological issues. Such works tend to place environmental responsibility on the shoulders of the individual citizen, aiming to educate but also to implicate them in the age of the Anthropocene. How and what these works aim to accomplish, are key to a better understanding the means of knowledge transfer and potential agents of change in the Anthropocene. We study three cases in this paper. These are examined through: (1) their potential to raise awareness or activate behavior change; (2) how well they are capable of making the catastrophic situations, which are invisible to most people, visible; and (3) how well they enable systemic change in the catastrophic situations. In the three cases studied, we find that they are successful in helping to raise awareness and even change individual behavior, they are successful in rendering the invisible visible, but they are incapable of engendering any systemic change of the catastrophic situations depicted. Keywords: Anthropocene; public art; eco-art installations; eco-design; raising awareness Citation: Cucuzzella, C. Making the Invisible Visible: Eco-Art and Design 1. Introduction against the Anthropocene. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3747. https:// Earth has experienced many planetary-scale shifts in its 4.5-billion-year history. The doi.org/10.3390/su13073747 first signs of life, in fact, forcefully altered the future of the planet. -

Public Art Policy

CITY OF GILROY PUBLIC ART POLICY VISION STATEMENT: The City of Gilroy’s Public Art Committee promotes a bold vision which exemplifies the City’s creativity and energy shaping the visual environment of our community. PURPOSE: The City of Gilroy (City) recognizes the importance of Public Art to the cultural, educational and economic well-being of its diverse population. These guidelines are for the purpose of establishing policies and procedures for implementing Public Art as recommended in the Arts & Culture Commission’s Cultural Plan, developed in 1997, and 1999 General Plan Update. GOALS: To promote the City’s interest in its aesthetic environment. To establish the Public Art Committee as an advisory committee to the Arts and Culture Commission to be responsible for developing the Public Art Plan; ensuring the quality of artworks created under the plan; and, developing budgets, funding strategies and scope of individual Public Art projects. To create an enhanced visual environment within the City and provide City residents with the opportunity to live with Public Art. To help build pride in our City and among its citizens. To promote tourism and economic vitality of the City by enhancing the City’s public facilities and surroundings through the incorporation of Public Art. To encourage creative collaboration among community members. To encourage the creation of quality Public Art throughout the City by promoting locally, regionally, nationally and internationally recognized artists. To educate, preserve, reflect and celebrate the rich, unique history and cultural diversity of the City and its citizens. To promote and encourage art viewed by the public in all of the City’s communities and neighborhoods and to support the residents’ involvement in determining the character of their City. -

Public Pedagogies of Arts-Based Environmental Learning and Education for Adults European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults 8 (2017) 1, S

Walter, Pierre; Earl, Allison Public pedagogies of arts-based environmental learning and education for adults European journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults 8 (2017) 1, S. 145-163 Empfohlene Zitierung/ Suggested Citation: Walter, Pierre; Earl, Allison: Public pedagogies of arts-based environmental learning and education for adults - In: European journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults 8 (2017) 1, S. 145-163 - URN: urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-140063 - DOI: 10.3384/rela.2000-7426.relaOJS88 http://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-140063 http://dx.doi.org/10.3384/rela.2000-7426.relaOJS88 in Kooperation mit / in cooperation with: http://www.ep.liu.se Nutzungsbedingungen Terms of use Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, persönliches und We grant a non-exclusive, non-transferable, individual and limited right to beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist using this document. ausschließlich für den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch This document is solely intended for your personal, non-commercial use. Use bestimmt. Die Nutzung stellt keine Übertragung des Eigentumsrechts an of this document does not include any transfer of property rights and it is diesem Dokument dar und gilt vorbehaltlich der folgenden Einschränkungen: conditional to the following limitations: All of the copies of this documents must Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle retain all copyright information and other information regarding legal Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen Schutz protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any way, to copy it for beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument nicht in irgendeiner Weise public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the document in public, to perform, abändern, noch dürfen Sie dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder distribute or otherwise use the document in public. -

Pandemic Response Racial Justice Initiative Environmental Analysis

Special 2020 Issue Vol. 53 No. 1 Pandemic Response Racial Justice Initiative Environmental Analysis The College transitions to remote learning Three areas of transformative action Celebrating 50 years President’s Message I write this message at the determination, endless creativity and a profound commitment to each and outright strange conditions, we found ways to broaden our to work through shifting mountains of logistics and multiple scenarios for end of a year that has continually other and our shared ideals. While Pitzer’s campus has been closed since academic and co-curricular ambitions. We kept innovating. Pitzer Now, delivering a Pitzer education in a pandemic. defied and redefined our sense mid-March, and we will start spring 2021 online, you will read how our Pitzer@Home, and the People’s Pitzer are just some of the programs That work goes on. In the midst of such uncertainty, we do know this: of reality. We have struggled community came together even as we were forced apart. These pages show that were born as faculty, students and staff created new platforms to Pitzer’s commitment to its brand of liberal arts education and core values at times to comprehend the how we individually and collectively rose to meet this moment and, as the address our community’s needs. On December 10, Pitzer and the Justice endures. When we return to campus, not everything will or should go moment we’re living in. We have Dean of Faculty Allen Omoto says, “learned from each other.” Education Initiative of The Claremont Colleges launched the country’s back to the way it was before. -

Thomas Erben Gallery Ecofeminism(S)

Thomas Erben Gallery ecofeminism(s) curated by Monika Fabijanska June 19 - July 24, 2020 Press Day: Thursday, June 18, 2020, 12-6pm Reopens: September 8-26, 2020 526 West 26th Street, Suite 412-413 New York, NY 10001 Gallery Hours: Tue - Sat, 10-6pm Summer Hours: Mon – Fri , 11-6pm (June 29-July 24) NEW INFORMATION (updated August 28, 2020) ecofemisnism(s) online: PRESS RELEASE PRESS KIT: WORK DESCRIPTIONS & IMAGES LIST OF ARTISTS LIST OF ARTWORKS IMAGES ESSAY EXHIBITION PRESS UPCOMING PROGRAMS: Thursday, September 10, 6:30 PM EST Christies’s webinar: Spotlight on ecofeminism(s) REGISTER This complimentary webinar explores the critically acclaimed group exhibition ecofeminism(s) at Thomas Erben Gallery. Exhibition curator Monika Fabijanska and gallerist Thomas Erben will join Christie’s Education’s Julie Reiss for a discussion about the show’s timeliness and the increasing centrality in the art world of art grounded in ecological and other human rights concerns. Wednesday, September 16, 6:30 PM EST Zoom conversation with Raquel Cecilia Mendieta, niece and goddaughter of Ana Mendieta and Mira Friedlaender, daughter of Bilge Friedlaender, moderated by Monika Fabijanska. LINK TO ZOOM Meeting ID: 969 1319 1806 Password: 411157 RECORDED PROGRAMS GALLERY WALKTHROUGH WITH THE CURATOR ZOOM CONVERSATIONS moderated by curator Monika Fabijanska: Wednesday, July 8, 6:30 PM EST Lynn Hershman Leeson Mary Mattingly Hanae Utamura Julie Reiss, Ph.D., Christie’s Education CLICK TO WATCH THE RECORDING Wednesday, July 15, 6:30 PM EST Aviva Rahmani Sonya Kelliher-Combs -

Title/Description of Lesson Andy Goldsworthy - Environmental Art

VViiissuuaalll && PPeerrffoorrmmiiinngg AArrttss PPrrooggrraamm,,, SSJJUUSSDD AArrttss CCoonnnneeccttiiioonnss Title/Description of Lesson Andy Goldsworthy - Environmental Art Grade Level: 7th – 12th Lesson Links Objectives/Outcomes Materials and Resources Vocabulary Procedures Criteria for Assessing Student Learning California Standards in Visual & Performing Arts Other Resources Objectives/Outcomes (Return to Links) • To introduce students to Environmental Art. • To introduce students to the Environmental Artist Andy Goldsworthy. • Students will create their own Environmental Art Sculpture using found natural objects and the Elements of Art. • Students will evaluate their own sculpture by writing a brief paper about their artwork. The students will have an art critique. Materials and Resources (Return to Links) • Natural materials such as grass, twigs, leaves, flowers, etc. • Student Handouts • Photographs and books of Andy Goldsworthy’s art and other examples of Environmental Art • Camera for documenting student artworks Visual & Performing Arts Program, SJUSD Author: Kristi Char Page 1 of 9 Art Connections Last Updated: 10/23/2011 Vocabulary (Return to Links) *Definitions taken from the Green Museum web site @ www.greenmuseum.org Environmental Art: Art that helps improve our relationship with the natural world. It is an umbrella term which encompasses eco-art, land art, ecoventions, earth art, earthworks, and art in nature. Ecological Art (Eco-art): A contemporary art movement which addresses environmental issues and often involves collaboration, restoration, and usually has a more activist agenda. Art in Nature: Art in nature projects are usually beautiful forms created in nature, using materials such as twigs, leaves, stones, flower petals, icicles, etc. They are usually small- scale projects which often involve an overt spiritual dimension and are seen by artists as healing rituals for the earth.