Can Britain Lead in Europe?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Issue

Scottish Left Review Issue 79 November/December 2013 £2.00 Comment Scottish Left Review Issue 79 November/December 2013 t is difficult to maintain constitutional Ineutrality at this tail-end of 2013. Of course we will continue to do our best to keep the SLR open as a space for Contents anyone on the Scottish left, a place where they can feel at home and contribute Comment .......................................................2 to a debate that stretches beyond the boundaries of party or constitutional Democracy in writing ....................................4 position. That is our duty as a magazine Jean Urquhart created expressly for that purpose. Solid foundations for change .........................6 But the duty lies not only on us to Michael Keating keep that space open but on all sides to fill that space. Because it can surely not Our share of the future ..................................8 be possible for us to face the desolation Robin McAlpine which lies across Scottish society in the dog-days of this unlucky year without Graveyard or get-together ..........................10 some sort of answer to what lies all Isobel Lindsay around us. Welfare Nation State ...................................12 What answer to Grangemouth? John McInally Facile talk of ‘the need to work together’ is an insult to the collective intelligence. Labour and the trade unions .......................14 All it states is that if we keep the fork Gregor Gall, Richard Leonard, Bob Crow and let others keep the knife, it will be impossible for us to eat on our own. That Real energy answers ...................................18 may not be a bad thing, but someone Andy Cumbers needs to explain why. -

Was There an Armenian Genocide?

WAS THERE AN ARMENIAN GENOCIDE? GEOFFREY ROBERTSON QC’S OPINION WITH REFERENCE TO FOREIGN & COMMONWEALTH OFFICE DOCUMENTS WHICH SHOW HOW BRITISH MINISTERS, PARLIAMENT AND PEOPLE HAVE BEEN MISLED 9 OCTOBER 2009 “HMG is open to criticism in terms of the ethical dimension. But given the importance of our relations (political, strategic and commercial) with Turkey ... the current line is the only feasible option.” Policy Memorandum, Foreign & Commonwealth Office to Minister 12 April 1999 GRQCopCover9_wb.indd 1 20/10/2009 11:53 Was there an Armenian Genocide? Geoffrey Robertson QC’s Opinion 9 October 2009 NOTE ON THE AUTHOR Geoffrey Robertson QC is founder and Head of Doughty Street Chambers. He has appeared in many countries as counsel in leading cases in constitutional, criminal and international law, and served as first President of the UN War Crimes Court in Sierra Leone, where he authored landmark decisions on the limits of amnesties, the illegality of recruiting child soldiers and other critical issues in the development of international criminal law. He sits as a Recorder and is a Master of Middle Temple and a visiting professor in human rights law at Queen Mary College. In 2008, he was appointed by the Secretary General as one of three distinguished jurist members of the UN Justice Council. His books include Crimes Against Humanity: The Struggle for Global Justice; The Justice Game (Memoir) and The Tyrannicide Brief, an award-winning study of the trial of Charles I. GRQCopCover9_wb.indd 2 20/10/2009 11:53 Was there an Armenian Genocide? Geoffrey Robertson QC’s Opinion 9 October 2009 PREFACE In recent years, governments of the United Kingdom have refused to accept that the deportations and massacres of Armenians in Turkey in 1915 -16 amounted to genocide. -

Who Runs the North East … Now?

WHO RUNS THE NORTH EAST … NOW? A Review and Assessment of Governance in North East England Fred Robinson Keith Shaw Jill Dutton Paul Grainger Bill Hopwood Sarah Williams June 2000 Who Runs the North East … Now? This report is published by the Department of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Durham. Further copies are available from: Dr Fred Robinson, Department of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Durham, Durham DH1 3JT (tel: 0191 374 2308, fax: 0191 374 4743; e-mail: [email protected]) Price: £25 for statutory organisations, £10 for voluntary sector organisations and individuals. Copyright is held collectively by the authors. Quotation of the material is welcomed and further analysis is encouraged, provided that the source is acknowledged. First published: June 2000 ISBN: 0 903593 16 5 iii Who Runs the North East … Now? CONTENTS Foreword i Preface ii The Authors iv Summary v 1 Introduction 1 2 Patterns and Processes of Governance 4 3 Parliament and Government 9 4 The European Union 25 5 Local Government 33 6 Regional Governance 51 7 The National Health Service 64 8 Education 92 9 Police Authorities 107 10 Regeneration Partnerships 113 11 Training and Enterprise Councils 123 12 Housing Associations 134 13 Arts and Culture 148 14 Conclusions 156 iii Who Runs the North East … Now? FOREWORD Other developments also suggest themselves. At their meeting in November 1998, the The present work is admirably informative and trustees of the Millfield House Foundation lucid, but the authors have reined in the were glad to receive an application from Fred temptation to explore the implications of what Robinson for an investigation into the they have found. -

Tke Newspaper of the Anti-Apartheid Moviement

TKE NEWSPAPER OF THE ANTI-APARTHEID MOVIEMENT TKE NEWSPAPER OF THE ANTI-APARTHEID MOVIEMENT 1 As spiraling viokence teans Soutb AfrIcan townsips apar, De Kkrc-k ylds to ANC pressures PsdentDe Klerk has been Jbted to act on the dangerous escalation of viofence in South Afica's tozvnsbips, under the strong prssure from the ANC's ultimatum in its open letter to himn at the beginning of April. But his belated mo~e on 2.May may not be enough to stare off a sen ous breakdoun in tbe peace process, or to calm down tbe inflamed situation on th5e grud, AFta 1Y-11111sa-37 kld MinisterVio.k. ln fact o-t a.d do~~ injurd in Soweto South African papers bad arid oter black totetuipa, and breen calling on Malan lo hunge r strikes by political cesign for ndsts, and the prisnnento denrand their release InternationalCnsiln (~e page 9) spoadinig frm of Jurist bad called for, Pretoria to at leat tour other VIok's retcm n til pitison, De Klerk announccd in repott onr Natal last yrac ilie whltesýo y parliatnent a And the weekly Snsatbscstn serie-s of measurro to curtheb reported: 'Sentnment la viol-send rerucetihe olstales runtling strongly asnong to negotitiuns. Western diplo-sts *. that Itelerting calls for tbe thet ANC dernand, are wltich we wer in 1986. We vould e back ontheltrevocable path to a total revolution. Rst to appease fi theight be pronrised tough new taws agamtt 'mllieation,' the strengtåentrsg of polire 'manpower and equipnenV, and special a-tons flan ttte to timne by the police and naflsary. -

ISC Annual Report 2003-2004

Intelligence and Security Committee Annual Report 2003–2004 Chairman: The Rt. Hon. Ann Taylor, MP Intelligence Services Act 1994 Chapter 13 Cm 6240 £10.50 Intelligence and Security Committee Annual Report 2003–2004 Chairman: The Rt. Hon. Ann Taylor, MP Intelligence Services Act 1994 Chapter 13 Presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty JUNE 2004 Cm 6240 £10.50 ©Crown Copyright 2004 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to The Licensing Division, HMSO, St Clements House, 2–16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] From the Chairman: The Rt. Hon. Ann Taylor, MP INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMITTEE 70 Whitehall London SW1 2AS 26 May 2004 Rt. Hon. Tony Blair, MP Prime Minister 10 Downing Street London SW1A 2AA In September 2003 the Committee produced a unanimous Report following our inquiry into Iraqi Weapons of Mass Destruction – Intelligence and Assessments. I now enclose the Intelligence and Security Committee’s Annual Report for 2003–04. This Report records how we have examined the expenditure, administration and policies of the three intelligence and security Agencies. We also report to you on a number of other Agency related matters and the wider intelligence community. -

Iraqi Weapons of Mass Destruction – Intelligence and Assessments

5972_ISC FC_BC_i 10/9/03 12:18 am Page c Intelligence and Security Committee Iraqi Weapons of Mass Destruction – Intelligence and Assessments Chairman: The Rt. Hon. Ann Taylor, MP Cm 5972 £10.50 5972_ISC FC_BC_i 10/9/03 3:11 pm Page i Intelligence and Security Committee Iraqi Weapons of Mass Destruction – Intelligence and Assessments Chairman: The Rt. Hon. Ann Taylor, MP Presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty SEPTEMBER 2003 Cm 5972 £10.50 5972_ISC ii_iv 10/9/03 12:17 am Page ii ©Crown Copyright 2003 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to The Licensing Division, HMSO, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] 5972_ISC ii_iv 10/9/03 12:17 am Page iii iii 5972_ISC ii_iv 10/9/03 12:17 am Page iv INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMITTEE The Rt. Hon. Ann Taylor, MP (Chairman) The Rt. Hon. James Arbuthnot, MP The Rt. Hon. Alan Howarth CBE, MP The Rt. Hon. The Lord Archer of Sandwell, QC Mr Michael Mates, MP The Rt. Hon. Kevin Barron, MP The Rt. Hon. Joyce Quin, MP The Rt. Hon. Alan Beith, MP The Rt. -

REGISTER of MEMBERS' FINANCIAL INTERESTS As at 12 October 2015

REGISTER OF MEMBERS’ FINANCIAL INTERESTS as at 12 October 2015 _________________ Abbott, Diane (Hackney North and Stoke Newington) 1. Employment and earnings Fees received for co-presenting BBC’s ‘This Week’ TV programme. Address: BBC Broadcasting House, Portland Place, London W1A 1AA. (Registered 04 November 2013) 11 September 2014, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 21 October 2014) 9 October 2014, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 21 October 2014) 16 October 2014, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 21 October 2014) 6 November 2014, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 02 December 2014) 27 November 2014, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 02 December 2014) 11 December 2014, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 14 January 2015) 18 December 2014, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 14 January 2015) 8 January 2015, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 14 January 2015) 15 January 2015, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 26 February 2015) 12 February 2015, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 26 February 2015) 26 February 2015, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 26 February 2015) 19 March 2015, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 27 March 2015) 26 March 2015, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 27 March 2015) 9 April 2015, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 26 May 2015) 23 April 2015, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 26 May 2015) 14 May 2015, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 03 June 2015) 4 June 2015, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 01 July 2015) 18 June 2015, received £700. Hours: 3 hrs. (Registered 01 July 2015) 16 July 2015, received £700. -

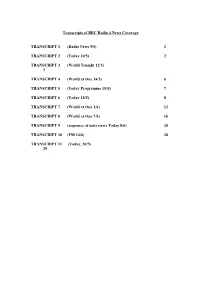

Transcripts of BBC Radio 4 News Coverage TRANSCRIPT 1

Transcripts of BBC Radio 4 News Coverage TRANSCRIPT 1 (Radio News 9/5) 2 TRANSCRIPT 2 (Today 10/5) 2 TRANSCRIPT 3 (World Tonight 12/5) 3 TRANSCRIPT 4 (World at One 14/5) 6 TRANSCRIPT 5 (Today Programme 15/5) 7 TRANSCRIPT 6 (Today 18/5) 8 TRANSCRIPT 7 (World at One 1/6) 12 TRANSCRIPT 8 (World at One 7/6) 16 TRANSCRIPT 9 (sequence of interviews Today 8/6) 20 TRANSCRIPT 10 (PM 14/6) 28 TRANSCRIPT 11 (Today, 20/5) 29 RADIO TRANSCRIPT 1 (Radio News 9/5) James Cox: William Hague has dismissed the breakaway Pro-Europe Conservatives as fanatics after a claim that next month’s European elections will finish him off as the Tory leader. The leader of the rebel group John Stevens said that despite Tory successes in the local council elections, the party’s split over Europe would see its share of the vote fall to around 25% in next month’s poll. But Mr Hague, interviewed by David Frost, thoroughly rejected the claims. Nicholas Jones reports. Nicholas Jones: The Conservatives knew that they could hardly fail to make significant gains in last week’s council elections. But because of the party’s continuing feud over Europe, the Tories’ chances of a continued recovery in next month’s European elections are clouded in uncertainty. The pro-European Conservatives’ leader, John Stevens, said William Hague was mad to have ruled out British membership of the Euro as far ahead as the next Parliament. He predicted that the Tory vote would drop to 25% and that it would be the end of Mr Hague. -

Appendix: Biographical Notes on Labour Mps, Meps and Peers

Appendix: Biographical Notes on Labour MPs, MEPs and Peers Abbreviations hp hereditary peer LBLG Leader, British Labour Group LEPLP Leader, European Parliamentary Labour Party LLP Leader of the Labour Party lp life peer MP Member of Parliament MEP Member of the European Parliament (elected since 1979) mep Member of the Commons or Lords delegated to the European Parliament before 1979 PM Prime Minister Albu, Austen (1903–93) MP 48–74 Archer, Peter (1926–) MP 66–92; lp 92 Ardwick, John (Beavan) (1910–94) lp 70; mep 75–79 Ashton, Joe (1933–) MP 68–01 Attlee, Clement (1883–1967) MP 22–55; LLP 35–55; PM 45–51; hp 55 Balfe, Richard (1944–) MEP 79– Barnes, Michael (1932–) MP 66–74 Barnett, Joel (1923–) MP 64–83; lp 83 Becket, Margaret (1943–) MP 83– Benn, Tony (1925–) MP 50–60, 63–83, 84–01 Berry, Roger (1948–) MP 92– Bevan, Aneurin (1897–1960) MP 29–60 Bevin, Ernest (1881–1951) MP 40–51 Bidwell, Sidney (1917–97) MP 66–92 Blair, Tony (1953–) MP 83–; LLP 94–; PM 97– Boothroyd, Betty (1929–) MP 73–2000; mep 75–77 Bradley, Tom (1926–) MP 62–83 (Lab –81; SDP –83) Brown, George (1914–85) MP 45–70; lp 70 Brown, Gordon (1951–) MP 83– Brown, Ron (1921–) MP 64–83 (Lab –81; SDP –83) Bruce, Donald (1912–) MP 45–50; lp 1974–; mep 75–79 Caborn, Richard (1943–) MEP 79–84; MP 83– Callaghan, James (1912–) MP 45–87; LLP 76–81; PM 76–79; lp 87 Castle, Barbara (1910–) MP 45–79; MEP 79–94; LBLG 79–85; lp 79 Castle, Ted (1907–79) lp 74; mep 75–79 Clinton Davis, Stanley (1928–) MP 70–83; EC 85–88; lp 90 Clwyd, Anne (1937–) MEP 79–84; MP 84– Coates, Ken (1930–) MEP -

Congress Report 2006

Congress Report 2006 The 138th annual Trades Union Congress 11-14 September, Brighton 4 Contents Page General Council members 2006 – 2007……………………………… .............4 Section one - Congress decisions………………………………………….........7 Part 1 Resolutions carried.............................. ………………………………………………8 Part 2 Motion remitted………………………………………………… ............................28 Part 3 Motions lost…………………………………………………….. ..............................29 Part 4 Motion withdrawn…………………………………………………………………….29 Part 5 General Council statements…………………………………………………………30 Section two – Verbatim report of Congress proceedings .....................35 Day 1 Monday 11 September ......................................................................................36 Day 2 Tuesday 12 September……………………………………… .................................76 Day 3 Wednesday 13 September...............................................................................119 Day 4 Thursday 14 September ...................................................................................159 Section three - unions and their delegates ............................................183 Section four - details of past Congresses ...............................................195 Section five - General Council 1921 – 2006.............................................198 Index of speakers .........................................................................................203 General Council Members Mark Fysh UNISON 2006 – 2007 Allan Garley GMB Bob Abberley Janice Godrich UNISON Public and Commercial -

Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums Statement of Accounts 2019/20

Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums Statement of Accounts 2019/20 This page has been left intentionally blank. Reference and Administration Details of Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums for the period ended 31 March 2020 Strategic Board Members: Rt. Hon Baroness Joyce Quin (Chair) Independent Cllr Ged Bell (Joint Vice Chair) Newcastle City Council Cllr Angela Douglas (Joint Vice Chair) Gateshead Council Professor Vee Pollock Newcastle University Cllr Sarah Day North Tyneside Council Cllr Alan Kerr South Tyneside Council Cllr Cath Davis North Tyneside Council (Rotating Member) Cllr Joan Atkinson South Tyneside Council (Rotating Member) Jonathan Blackie Independent Member Sarah Green Independent Member Helen Cadzow Independent Member (Appointed 28/06/2019) Director: Iain Watson Head Office: Discovery Museum, Blandford Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 4JA Auditors: MHA Tait Walker, Bulman House, Regent Centre, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE3 3LS Solicitors: John Softly, Newcastle City Council, Civic Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 8QH STRUCTURE, GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT Nature of governing document Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums (TWAM) is a joint service of the four local authorities on Tyneside: Newcastle (which acts as lead authority and legal body), South Tyneside, North Tyneside, and Gateshead, with additional support and contributions from the Arts Council England (ACE). The relationship between, and commitment of, the partners is enshrined in the Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums Joint Agreement. The Joint Agreement lays out the terms and conditions of the relationship. Policy and decision making is undertaken by the Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums Strategic Board and key decisions are outlined in the Corporate Plan 2018-2022. Appropriate consultation takes place about budget priorities and budget proposals, which shapes the budget decisions that are made. -

Visiting Parliamentary Fellowship Celebrating 25 Years 1994-2019

VISITING PARLIAMENTARY FELLOWSHIP CELEBRATING 25 YEARS 1994-2019 St Antony's College 1 Roger Goodman, Warden of St Antony’s At a recent breakfast with the students, it was decided that the College should do more to advertise what distinguished it from other colleges in Oxford. St Antony’s is: The Oxford college founded by a Frenchman The Oxford college with two Patron Saints (St Antony of Egypt and St Antony of Padua) The Oxford college where almost 90% of the 500 graduate students are from outside UK and the alumni come from 129 countries The Oxford college with international influence: ‘In the mid-2000s, 5% of the world’s foreign ministers had studied at St Antony’s’ (Nick Cohen, The Guardian, 8 Nov, 2015) The Oxford college mentioned in the novels of both John Le Carré and Robert Harris The Oxford college which holds the most weekly academic seminars and workshops The Oxford college with two award-winning new buildings in the past decade To this list can be added: St Antony’s is the Oxford college with a Visiting Parliamentary Fellowship (VPF). There is no other Oxford college that can boast such a list of parliamentarians responsible for a seminar programme over such a long period of time. The College is immensely proud of the Fellowship and greatly indebted to all those who have held it over the past 25 years. We were very grateful to those who have were able to come to the 25th anniversary celebration of the Fellowship programme at the House of Commons on 24 April 2019 and for the many generous letters from those who could not.