Subaltern Aspirations in Three Films by Bala, Kumararaja and Mysskin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camp Sitting at Chennai, Tamil Nadu Full Commission V

NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION (LAW DIVISION – FULL COMMISSION BRANCH) CAMP SITTING AT CHENNAI, TAMIL NADU FULL COMMISSION CAUSE LIST CORAM: Mr. Justice H.L. Dattu - Chairperson Mr. Justice P.C. Pant - Member Mrs. Jyotika Kalra - Member Dr. D.M. Mulay - Member Friday, 13th September, 2019 at 10.00 A.M. Venue: Anna Centenary Library, Gandhi Mandapam Road, Surya Nagar, Kotturpuram, Chennai, Tamil Nadu S. Case No. Complainant/In Name of authority No timation received from 1. 512/22/0/2019 Suo-motu Principal Secretary, Suo-motu cognizance of a news item Labour and published in “Business Line” dated Employment (M2) 21.02.2019 highling the plight of thousands Deptt., Govt of Tamil of garmet factory workers in Tamil Nadu. Nadu 2. 896/22/37/2010 Shri Devika Chief Secretary Illegal arrest of five members of Fact Finding Prasad Director General of Team by Veeravanallur Police, Tiruneveli, Shri Henri Police Tamil Nadu Tiphagne 3. 590/22/42/2019 Shri A.P. Disitrict Collector, Complaint regarding families living without Gowdhamasidha Villupuram, Tamil Nadu shelter in Villupuram District, Tamil Nadu rthan 4. 554/22/12/2017 Shri T.D. Commissioner, Avadi Inaction by District Administration in regard Ramalingam Municipality to the complaint of stagnation of drainage District Collector and rain water in area in Awadi Municipality Tiruvallur 5. 807/22/13/2019 Shri Radhakanta The District Magistrate Complaint regarding gang-rape of a 11 year Tripathy Chennai old deaf girl in Chennai on 17.07.2018 for The Commissioner of which seventeen men were charged. Police,Chennai 6. 308/22/39/2019 Suo-motu Additional Chief Suo-motu cognizance of a news report carried Secretary Home out by “News 18” regarding sexual abuse of 15 (Pol.XII) Department, minor girls who were rescused from a Home in Tamil Nadu Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu. -

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal , Free-Standing Articles Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema 2

Edinburgh Research Explorer Madurai Formula Films Citation for published version: Damodaran, K & Gorringe, H 2017, 'Madurai Formula Films', South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (SAMAJ), pp. 1-30. <https://samaj.revues.org/4359> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (SAMAJ) General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal Free-Standing Articles Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema Karthikeyan Damodaran and Hugo Gorringe Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic version URL: http://samaj.revues.org/4359 ISSN: 1960-6060 Electronic reference Karthikeyan Damodaran and Hugo Gorringe, « Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema », South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], Free-Standing Articles, Online since 22 June 2017, connection on 22 June 2017. URL : http://samaj.revues.org/4359 This text was automatically generated on 22 June 2017. -

Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions Poster Sessions Continuing

Sessions and Events Day Thursday, January 21 (Sessions 1001 - 1025, 1467) Friday, January 22 (Sessions 1026 - 1049) Monday, January 25 (Sessions 1050 - 1061, 1063 - 1141) Wednesday, January 27 (Sessions 1062, 1171, 1255 - 1339) Tuesday, January 26 (Sessions 1142 - 1170, 1172 - 1254) Thursday, January 28 (Sessions 1340 - 1419) Friday, January 29 (Sessions 1420 - 1466) Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions More than 50 sessions and workshops will focus on the spotlight theme for the 2019 Annual Meeting: Transportation for a Smart, Sustainable, and Equitable Future . In addition, more than 170 sessions and workshops will look at one or more of the following hot topics identified by the TRB Executive Committee: Transformational Technologies: New technologies that have the potential to transform transportation as we know it. Resilience and Sustainability: How transportation agencies operate and manage systems that are economically stable, equitable to all users, and operated safely and securely during daily and disruptive events. Transportation and Public Health: Effects that transportation can have on public health by reducing transportation related casualties, providing easy access to healthcare services, mitigating environmental impacts, and reducing the transmission of communicable diseases. To find sessions on these topics, look for the Spotlight icon and the Hot Topic icon i n the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section beginning on page 37. Poster Sessions Convention Center, Lower Level, Hall A (new location this year) Poster Sessions provide an opportunity to interact with authors in a more personal setting than the conventional lecture. The papers presented in these sessions meet the same review criteria as lectern session presentations. For a complete list of poster sessions, see the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section, beginning on page 37. -

Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Digitized Theses Digitized Special Collections 2011 CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA Ganga Rudraiah Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses Recommended Citation Rudraiah, Ganga, "CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA" (2011). Digitized Theses. 3315. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses/3315 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Special Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA r , ' (Spine title: CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by : Ganga Rudraiah Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ganga Rudraiah 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION r Supervisor Examiners Dr. Christopher E. Glttings Dr. James Prakash Younger Supervisory Committee Dr. Constanza Burucúa Dr. Chris Holmlund The thesis by Ganga Rudraiah entitled: Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Date Chair of the Thesis Examination Board Abstract The star machinery of Tamil cinema presents itself as a nearly unfathomable system that produces stars and politicians out of actors and fans out of audiences in an organized fashion. -

Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

South Asian Popular Culture ISSN: 1474-6689 (Print) 1474-6697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsap20 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard To cite this article: Dickens Leonard (2015) Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films, South Asian Popular Culture, 13:2, 155-173, DOI: 10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Published online: 23 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsap20 Download by: [University of Hyderabad] Date: 25 October 2015, At: 01:16 South Asian Popular Culture, 2015 Vol. 13, No. 2, 155–173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard* Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India This paper analyses contemporary, popular Tamil films set in Madurai with respect to space and caste. These films actualize region as a cinematic imaginary through its authenticity markers – caste/ist practices explicitly, which earlier films constructed as a ‘trope’. The paper uses the concept of Heterotopias to analyse the recurrence of spectacle spaces in the construction of Madurai, and the production of caste in contemporary films. In this pursuit, it interrogates the implications of such spatial discourses. Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films To foreground the study of caste in Tamil films and to link it with the rise of ‘caste- gestapo’ networks that execute honour killings and murders as a reaction to ‘inter-caste love dramas’ in Tamil Nadu,1 let me narrate a political incident that occurred in Tamil Nadu – that of the formation of a socio-political movement against Dalit assertion in December 2012. -

ANNUAL REPORT June 2016 – May 2017

MOTHER TERESA WOMEN’S UNIVERSITY KODAIKANAL ANNUAL REPORT June 2016 – May 2017 Edited by : Dr.A.Muthu Meena Losini Assistant Professor Department of English Mother Teresa Women‘s University Kodaikanal Technical Assistance by : Mrs.T.Amutha Technical Assistant Department of Physics Mother Teresa Women‘s University Kodaikanal MOTHER TERESA WOMEN‟S UNIVERSITY (Accredited with „B‟ Grade by NACC) KODAIKANAL – 624 101 This is the Annual Report for the period June 2016 – May 2017 of the Mother Teresa Women‘s University, Kodaikanal. The report gives all Academic, Administrative and other relevant details pertaining to the period June 2016 – May 2017. I take this occasion to thank all the members of the Executive Council, Academic Committee and Finance Committee for all their participation and contribution to the growth and development of the University and look forward to their continued advice and guidance. Dr. G. Valli VICE-CHANCELLOR INTRODUCTION The Executive Council has great pleasure in presenting to the Academic Committee, the Annual report for the period June 2016- May 2017 as per the requirement of the section 26 of Chapter IV of Mother Teresa Women‘s University Act 1984. The report outlines the various activities which have paved for the growth and development of the University through the period June 2016 –May 2017 in the areas of Teaching, Research and Extension; it provides a detailed account of various Academic Achievements, Introduction of new Innovative Courses, Conduct of Seminar/ Workshop/ Conferences at Regional, National and International levels and its extension activities. OFFICERS AND AUTHORITIES OF THE UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR - HIS EXCELLENCY HON‘BLE Banwarilal Purohit Governor of Tamil Nadu PRO – CHANCELLOR - HONOURABLE Thiru. -

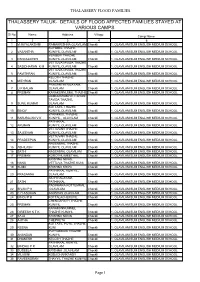

Thalassery Taluk- Details of Flood Affected Families Stayed at Various Camps

THALASSERY FLOOD FAMILIES THALASSERY TALUK- DETAILS OF FLOOD AFFECTED FAMILIES STAYED AT VARIOUS CAMPS Sl No Name Address Village Camp Name 1 2 3 4 6 1 VIJAYALAKSHMI RAMAKRISHNA,OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL KUYIMBIL THAZHE 2 VASANTHA KUNIYIL,OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL VENGERI THAZHE 3 PANKAJAKSHI KUNIYIL,OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL VETTUVATAVIDA THAZHE 4 SASIDHARAN K M KUNIYIL,OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL VETTUVATAVIDA THAZHE 5 PAVITHRAN KUNIYIL,OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL KELOTH THAZHE 6 MITHRAN OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL PRASANTHI NILAYAM, 7 U K BALAN OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL 8 PREMAN KANAKUNNUMAL THAZHE Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL DAMODARAM,VETTUVAN TAVIDA THAZHE, 9 SUNIL KUMAR OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL KOTTAYIL THAZHE 10 BINOY KUNIYIL,OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL VARAKKUL THAZHE 11 BABURAJAN V K KUNIYIL , OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL PATHIKKAL 12 ARUNAN KUNIYIL,OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL VETTUVAN THAZHE 13 SAJEEVAN KUNIYIL,OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL VETTUVAN THAZHE 14 PRADEEPAN KUNIYIL,OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL NADEMMAL THAZHE 15 ABHILASH KUNIYIL OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL 16 SATHI NADEMMAL OLAVILAM Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL 17 PREMAN KOROTHU MEETHAL Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL KRISHNA NIVAS, 18 NANU VETTUVA THAZHE KUNI, Chockli 1. OLAVILAM SUM ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL 19 SUMA KRISHNA KRIPA Chockli 1. -

CII-ITC Sustainability Awards 2008 Chemplast Sanmar Gets Recognition in the Large Business Category Awards

1 Sanmar Holdings Limited Sanmar Chemicals Corporation Sanmar Engineering Corporation Chemplast Sanmar Limited BS&B Safety Systems (India) Limited PVC Flowserve Sanmar Limited Chlorochemicals Sanmar Engineering Services Limited Trubore Piping Systems Fisher Sanmar Limited TCI Sanmar Chemicals LLC (Egypt) Regulator Valves Tyco Sanmar Limited Sanmar Metals Corporation Xomox Sanmar Limited Sanmar Foundries Limited Pacific Valves Division Sand Foundry Investment Foundry Sanmar Speciality Chemicals Limited Machine Shop ProCitius Research Matrix Metals LLC Intec Polymers Keokuk Steel Castings Company (USA) Performance Chemicals Richmond Foundry Company (USA) Bangalore Genei Acerlan Foundry (Mexico) Cabot Sanmar Limited NEPCO International (USA) Sanmar Ferrotech Limited Eisenwerk Erla GmBH (Germany) Sanmar Shipping Limited The Sanmar Group 9, Cathedral Road, Chennai 600 086. Tel.: + 91 44 2812 8500 Fax: + 91 44 2811 1902 2 In this issue... Momentous Moments MNC Flying to the Moon 4 MNC Celebrates 19th Anniversary 28 5th National Workshop on Early Intervention for Cover Story Mental Retardation 29 Sanmar’s Egyptian Sojourn 8 Social Responsibility Guest Column India’s Environment Ambassador Bata by Choice -Thomas G Bata 12 Voyages to the Arctic 30 A New Financial World Order - Arvind Subramanian 15 CII-Tsunami Rehabilitation Scorecard 32 Celebrating Art Chemplast Sanmar Distributes Rice in Hurricane- ravaged Villages in Cuddalore & Karaikal 34 Strumming to Spanish Music 19 Renovation of Park at Karaikal 35 Sruti Magazine Celebrates Silver Jubilee 20 The First Mrs Madhuram Narayanan Endowment Lecture 36 Pristine Settings Around Sanmar 22 Events Awards Sanmar Stands Tall 37 Flowserve Sanmar’s Training Centre 24 Trubore Dealers’ Meet 25 Legends from the South The 9th AIMA-Sanmar National Management Quiz 26 Padmini 42 Matrix can be viewed at www.sanmargroup.com Designed and edited by Kalamkriya Limited, 9, Cathedral Road, Chennai 600 086. -

Chevalior Sivaji Ganesan‟S Tamil Film Songs Not Only Emulated the Quality of the Movie but Also Contains Ethical Imports That

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: A Arts & Humanities - Psychology Volume 20 Issue 10 Version 1.0 Year 2020 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Chevalior Sivaji Ganesan‟S Tamil Film Songs Not Only Emulated the Quality of the Movie but also Contains Ethical Imports that can be Compared with the Ethical Theories – A Retrospective Reflection By P.Sarvaharana, Dr. S.Manikandan & Dr. P.Thiyagarajan Tamil Nadu Open University Abstract- This is a research work that discusses the great contributions made by Chevalior Shivaji Ganesan to the Tamil Cinema. It was observed that Chevalior Sivaji film songs reflect the theoretical domain such as (i) equity and social justice and (ii) the practice of virtue in the society. In this research work attention has been made to conceptualize the ethical ideas and compare it with the ethical theories using a novel methodology wherein the ideas contained in the film song are compared with the ethical theory. Few songs with the uncompromising premise of patni (chastity of women) with the four important charateristics of women of Tamil culture i.e. acham, madam, nanam and payirpu that leads to the great concept of chastity practiced by exalting woman like Kannagi has also been dealt with. The ethical ideas that contain in the selection of songs were made out from the selected movies acted by Chevalier Shivaji giving preference to the songs that contain the above unique concept of ethics. GJHSS-A Classification: FOR Code: 190399 ChevaliorSivajiGanesanSTamilFilmSongsNotOnlyEmulatedtheQualityoftheMoviebutalsoContainsEthicalImportsthatcanbeComparedwiththeEthicalTheo riesARetrospectiveReflection Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2020. -

FORM 11 List of Applications for Objecting to Particulars in Entries In

ANNEXURE 5.10 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 11 List of Applications for objecting to particulars in entries in electoral roll received in Form 8 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Attur Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial number Date of Name (in full) of elector Particulars of entry Nature of Date of Time of $ of receipt objecting objected at objection hearing* hearing* application Part number Serial number 1 16/11/2020 Boopathi 173 821 2 16/11/2020 Aravinthkumar 265 666 £ In case of Union territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir @ For this revision for this designated location Date of exhibition at designated Date of exhibition at Electoral * Place, time and date of hearings as fixed by electoral registration officer location under rule 15(b) Registration Officer¶s Office $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each under rule 16(b) designated location 23/11/2020 ANNEXURE 5.10 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 11 List of Applications for objecting to particulars in entries in electoral roll received in Form 8 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Attur Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 17/11/2020 17/11/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial number Date of Name (in full) -

Analysis on Director Ram's Films

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347-4564; ISSN (E): 2321-8878 Vol. 6, Issue 12, Dec 2018, 155-166 © Impact Journals ANALYSIS ON DIRECTOR RAM’S FILMS Arivuselvan. S & Aasita Bali Research Scholar, Department of Media and Communication Studies, Christ (Deemed to be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India Received: 15 Nov 2018 Accepted: 12 Dec 2018 Published: 18 Dec 2018 ABSTRACT This case study aims to explore the expertise of a budding, yet prolific director–Director Ram. The paper goes through the work of Director Ram in the Tamil film Industry (Kattradhu Tamizh, ThangaMeengal, Taramani) and aims to focus on the content of the films directed by him. The researcher, in his paper analyzes the types and kind of movies that the director has been a part of and the different types of techniques that he adopted and executed in his films. The researcher also analyses in detail, the type of character and highlighted the multifaceted role of women as portrayed in his films. KEYWORDS: Direction, Cinematography, Protagonist, Women, Characters, Film Industry, Globalization INTRODUCTION Indian cinema has been a standout amongst the most continually developing film ventures everywhere throughout the world. The wide variety and the number of dialects that are used in the nation, make the Indian film industry standout as the leading film producing unit. Indian film is a plethora of numerous dialects, classifications, and social orders. In any case, in a multilingual nation like our own, the significant focal point of the movies is on Bollywood. It is not valid if critiques and reviewers point out that the industry is notwithstanding the pressure or competition from Hollywood. -

Mess Bill for December 2013

DECEMBER 2013 MESS BILL LIST ( REGULAR & VACATION MESS) A & B MESS srno Roll No Name Mess total 1 101113001 A J SUDHI A & B 1390 2 101113002 ADAPALA ARAVINDH BABU A & B 1390 3 101113004 AMIT KUMAR A & B 1390 4 101113005 AMITHVISHAL. P A & B 1515 5 101113007 ANGAMBA NAMEIRAKPAM A & B 1562 6 101113008 ANIRUDH DEORAH A & B 1620 7 101113010 ANWIN P S A & B 1714 8 101113011 ARUN. M.V A & B 1340 9 101113012 ASHISH RANJAN A & B 1340 10 101113014 CHANDU SAI TARUN A & B 1759 11 101113016 GUDALA DILEEP A & B 1390 12 101113017 HUKUMU RIO DEBBARMA A & B 1599 13 101113019 JULIAN DIVAKAR A A & B 1190 14 101113020 KARNIK N HEGDE A & B 1390 15 101113021 KOKKIRALA HARSHA VARDHAN RAO A & B 1390 16 101113022 KUMAVATH CHANDRA SHEKHAR NAIK A & B 1412 17 101113024 M GOKUL ANAND A & B 1390 18 101113025 MADAM MALLIKARJUN A & B 1390 19 101113026 MAHONRING SHAIZA A & B 1801 20 101113027 MOHAMMED SIRAJUDDIN A & B 1390 21 101113029 NIKHIL CHOPRA GALIMOTU A & B 1190 22 101113030 NILESH ROY A & B 1593 23 101113034 RAFAEL WILLIAMS MANNERS A & B 1390 24 101113035 RAHUL SOMARAJAN NAIR A & B 1340 25 101113036 RAVIPUDI SRIKANTH A & B 1340 26 101113037 S N MITHUN BALAJI A & B 1340 27 101113038 S P GANESHAN A & B 1390 28 101113039 S SANTHOSH A & B 1728 29 101113040 S SIDDHARTH A & B 1390 30 101113042 SHAHUL SHANAVAS S A & B 1390 31 101113043 SIDHARTH.K A & B 1390 32 101113045 SRIRAM R A & B 1540 33 101113048 YOKESHWAR ELANGOVAN A & B 1390 34 102113001 A C M ABINESH KUMAR A & B 1390 35 102113002 AKSHAY MURALI A & B 1500 36 102113003 AMAN KUMAR BAKOLIA A & B 1390 37 102113005 ANIKET GUPTA A & B 1340 38 102113006 ANNAM JHANSI SHRAVAN A & B 1557 39 102113008 AREPALLI PHANENDRA A & B 1390 40 102113009 ARVIND PARI A & B 1340 41 102113010 ARVIND SRIVATSAVA.