Concert Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where to Study Jazz 2019

STUDENT MUSIC GUIDE Where To Study Jazz 2019 JAZZ MEETS CUTTING- EDGE TECHNOLOGY 5 SUPERB SCHOOLS IN SMALLER CITIES NEW ERA AT THE NEW SCHOOL IN NYC NYO JAZZ SPOTLIGHTS YOUNG TALENT Plus: Detailed Listings for 250 Schools! OCTOBER 2018 DOWNBEAT 71 There are numerous jazz ensembles, including a big band, at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. (Photo: Tony Firriolo) Cool perspective: The musicians in NYO Jazz enjoyed the view from onstage at Carnegie Hall. TODD ROSENBERG FIND YOUR FIT FEATURES f you want to pursue a career in jazz, this about programs you might want to check out. 74 THE NEW SCHOOL Iguide is the next step in your journey. Our As you begin researching jazz studies pro- The NYC institution continues to evolve annual Student Music Guide provides essen- grams, keep in mind that the goal is to find one 102 NYO JAZZ tial information on the world of jazz education. that fits your individual needs. Be sure to visit the Youthful ambassadors for jazz At the heart of the guide are detailed listings websites of schools that interest you. We’ve com- of jazz programs at 250 schools. Our listings are piled the most recent information we could gath- 120 FIVE GEMS organized by region, including an International er at press time, but some information might have Excellent jazz programs located in small or medium-size towns section. Throughout the listings, you’ll notice changed, so contact a school representative to get that some schools’ names have a colored banner. detailed, up-to-date information on admissions, 148 HIGH-TECH ED Those schools have placed advertisements in this enrollment, scholarships and campus life. -

Surprise Ruling Decertifies Retiree Class in Lawsuit

Thursday, NOVEMBER 30, 2017 VOLUME LIV, NUMBER 48 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING DUBLIN, LIVERMORE, PLEASANTON, SUNOL Surprise Ruling Decertifies Retiree Class in Lawsuit An Oakland court reversed itself this week, decertifying the “class” “whether each class member has in fact been damaged at all.” of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory retirees three years after UC health care benefits were available to the LLNL retirees from certifying it in a lawsuit aimed at regaining University of California the time of the Laboratory’s founding in 1952 until 2008, shortly after See Inside Section A health care. a for-profit consortium took over for the University as manager of the Section A is filled with The surprise decertification order was issued Monday by Superior national defense laboratory. information about arts, people, Court Judge George Hernandez, the judge who certified the class in 2014. The retirees considered the loss of UC health care to be a violation of promises made during their careers at the Laboratory -- promises on entertainment and special events. In his reversal, Hernandez acknowledged that certification is normally established early in a legal proceeding. That is not an “iron clad stan- which some of them based career decisions. They filed suit in 2010, and There are education stories, a dard,” however, particularly if it becomes clear that “individual issues the suit became a class action four years later. variety of features, and the arts will engulf the litigation,” he wrote. Following certification, the retirees spent many thousands of dollars and entertainment and That appears to be the case now, he indicated. -

Discography (As Leader) in Order of Release

Discography (as leader) in order of release: 1.)“New York City Jazz” Bill Warfield Big Band – Interplay Records ‐ 1990 Recorded at National Edison Studios, NYC, Feb 28, Mar 1 and 2, 1988, produced by Mike Abene, engineered by Craig Bishop, Mixed at Sorcerer Sound, NYC. Leader, trumpet, arranger – Bill Warfield Reeds: Andy Fusco, Dan Block, Dave Brandom, Rich Perry, Bob Hanlon, and Tom Olin Trumpets: Earl Gardner, Joe Mosello, Jeff Parke, Jerry Sokolov, Dean Pratt, Jim Powell Trombones: Matt Haviland, Earl McIntyre, Doug Purviance, Dan Levine Piano: Ted Rosenthal, Bass: Mike Richmond, Drums: Bob Weller, Percussion: Dan Sadownick Selections: 1.) Totem Pole – comp. Lee Morgan, arr. Bill Warfield Bill Warfield – trumpet, Dan Block – alto sax 7:00 2.) Streetcorner Supermarket – comp. and arr. by Bill Warfield Bob Weller – drums, Rich Perry – tenor saxophone 6:51 3.) In Your Own Sweet Way – comp Dave Brubeck, arr. Bill Warfield Matt Haviland – trombone, Ted Rosenthal – piano 6:30 4.) Somewhere Over The Rainbow – comp. Harold Arlen, arr. Bill Warfield Bill Warfield – trumpet 4:56 5.) Positively Wall Street – comp. and arr. Bill Warfield Tom Olin – baritone saxophone, Jerry Sokolov – trumpet 7:05 6.) Scootzie – comp. and arr. Bill Warfield Bob Hanlon – tenor saxophone 5:12 7.) I Loves You Porgy – comp. George Gershwin, arr. Bill Warfield Andy Fusco – alto saxophone 7:11 8.) Waltz For A Lonely Woman – comp. and arr. Bill Warfield Ted Rosenthal – piano 4:56 9.) With A Song In My Heart – comp. Richard Rodgers, arr. Bill Warfield Mike Richmond – bass, Dan Block – clarinet 6:14 10.) Naima – comp. John Coltrane, arr. -

Colorful Characters

Livermore-Amador Symphony Lara Webber, Music Director & Conductor Arthur P. Barnes, Music Director Emeritus Saturday, February 23, 2019, 8 p.m. Bankhead Theater, Livermore Colorful Characters William Tell Overture Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868) Cello Concerto No. 1 Joseph Haydn in C major, Hob. VIIb/1—1st movement (1732–1809) Alexander Canicosa-Miles, soloist Soirées Musicales Benjamin Britten Suite of Movements from Rossini (1913–1978) I. March II. Canzonetta III. Tirolese IV. Bolero V. Tarantella INTERMISSION with entertainment in the lobby by Element 116 Piano Concerto No. 1 Franz Liszt in E-flat major (1811–1886) Daniel Mah, soloist Billy the Kid Suite Aaron Copland (1900–1990) Introduction: The Open Prairie Street in a Frontier Town Mexican Dance and Finale Prairie Night (Card Game) Gun Battle Celebration (after Billy’s Capture) Billy’s Death The Open Prairie Again The audience and performers are invited to enjoy cookies, cider, coffee, and sparkling wine in the lobby after the concert at a reception hosted by the Livermore-Amador Symphony Guild. Music Director position underwritten by the Chet and Henrietta Fankhauser Trust Orchestra Conductor Cello Horn Lara Webber Peter Bedrossian Christine-Ann Immesoete Principal Principal First Violin Alan Copeland James Hartman Sara Usher Aidan Epstein Bryan Waugh Concertmaster Nathan Hunsuck H. Robert Williams Juliana Zolynas Hildi Kang Assistant Trumpet Concertmaster Joanne Lenigan Paul Pappas Michael Portnoff Norman Back Principal Feliza Bourguet String Bass Bob Bryant Judy Eckart Markus Salasoo -

Kaiser Dublin Medical Complex to Open Officially on May 20 by Ron Mcnicoll the First Day of Operation for Area, with Room for Growth

Thursday, MAY 16, 2019 VOLUME LVI, NUMBER 20 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING DUBLIN, LIVERMORE, PLEASANTON, SUNOL Kaiser Dublin Medical Complex To Open Officially on May 20 By Ron McNicoll The first day of operation for area, with room for growth. Multi-specialty Hub. With 140,000 Kaiser patients the new Kaiser Medical Offices The staff of 500, taken from “There is nothing like it right in the Tri-Valley, from San Ra- and Cancer Center in Dublin will other Kaiser locations in Contra now in Northern “California. It mon, Pleasanton, Livermore and See Inside Section A be May 20. Costa and Alameda counties, will will be closer to where patients Dublin, heavy use is expected. The 226,000-square-foot multi- all be present when the facility live, who have had to go to Walnut The three-hour Open House for Section A is filled with specialty hub, which includes the opens, Physician Site Leader Dr. Creek, and outside Kaiser for their members on May 11 drew 5000 information about arts, people, Dublin Medical Office, Cancer Steve Zurnacian stated. care needs,” said Zurnacian. people, about double the number entertainment and special events. Center, surgery center and urgent The facility will be more than The shift of care delivery from who had registered for a tour of There are education stories, a care, is located at 3100 Dublin just another Kaiser Medical Of- the hospital to outpatient settings is the physical plant. variety of features, and the arts Blvd. It will provide services for fices site, added Zurnacian. -

Former Congressmember, Arms Negotiator Ellen Tauscher Dies

Thursday, MAY 2, 2019 VOLUME LVI, NUMBER 18 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING DUBLIN, LIVERMORE, PLEASANTON, SUNOL Former Congressmember, Arms Negotiator Ellen Tauscher Dies Former Congresswoman Ellen While in Congress, she served Secretary of State for Arms Con- Secretary of State Hillary Clin- Tauscher, who represented the on the House Armed Services trol and International Security Af- ton, told Politico Magazine that 10th Congressional District from Committee and chaired its Strate- fairs in the Obama administration, Tauscher was "the most important See Inside Section A 1997 to 2009, has died. The district gic Forces Subcommittee, making negotiating the New START stra- person in negotiations of the New Section A is filled with included Livermore and a portion her tenure particularly important tegic arms treaty with the Russian START Treaty.” It limits the num- information about arts, people, of the I-680 corridor. to Lawrence Livermore National Federation. She developed her ber of nuclear warheads Russia entertainment and special events. Her family announced her death Laboratory (LLNL) and Sandia knowledge and interest in nuclear and the U.S. can deploy. "In my There are education stories, a from pneumonia complications National Laboratories. weapons control as a result off her opinion, it would not have hap- variety of features, and the arts on April 29 at Stanford Medical Tauscher resigned from Con- connection with LLNL. pened without her," Clinton said and entertainment and Center on April 29. She was 67. gress in 2009 to become Under Tauscher’s good friend, former (See TAUSCHER, page 5) bulletin board. Dublin Board, Overhaul of Teachers Sign Paratransit 2019-20 Contract Services The Dublin Unified School On the Table District (DUSD) and the Dublin By Ron McNicoll Teachers Association (DTA) have The Pleasanton City Council signed a contract that runs through will face choices listed in a two- the 2019-20 school year. -

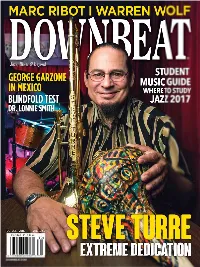

Music Guide 13 the Beat 180 Master Class by ELDAR DJANGIROV 194 Blindfold Test Where to Study Jazz 2017 24 Players 182 Pro Session Dr

October 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 10 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

Resurrection Remembered

r." - 'mop FORUM SPORTS Staffers consider traffic tickets, book lists, Friday SJSU tennis stomps Banana Slugs 6-3, household hints for cleaning challenged then lobs them back home to Santa Cruz See page 2 SPARTAN DAILY See page 4 Volume 110, No. 49 Serving San Jose State University Since 1934 April 10, 1998 Rhythm One-fourth Resurrection master remembered 'sticks' third day after his crucifixion Christians celebrate Jesus Christ rose from the dead, and by that resurrection, con- Jesus' death on the quered death. cross, ascension into His believers would subse- to beat quently share his victory over sin, death and the devil, accord- By Carol Dillon Heaven on third day Starr Writer ing to Aruta. By Yvette Anna Trejo "Easter is a celebration because stdit Duke Ellington called him it's a message proving Jesus rose only the world's greatest from the dead," Christian "not For many Christians, world's this Church of Santa Clara Minister drummer, but also the Friday will be better than most. greatest musician." He was Gene Feaster said. "I rejoice in It is, after ill, (Mod Friday. referring to Louis Bellson, the what he did for me. Good Friday is the Friday guest artist at San Jose State "A Christian looks at Jesus' before Easter and the day in the resurrection as eternal life with University's Percussion Ensemble Holy Week im which the yearly on him. It's our hope of eternal life Monday. Cl)mmenwrati,in of the crucifix- Bellson first picked because he now lives," he said. up the in ofJesus Christ is observed. -

Bill Warfield Big Band For

Piano: Ted Rosenthal, Bass: Mike Richmond, Drums: Bob Weller Bob Drums: Richmond, Mike Bass: Rosenthal, Ted Piano: Piano: Greg Cogan, Guitar: Chris Rosenberg, Bass: Mike Richmond, Drums: Tim Horner Tim Drums: Richmond, Mike Bass: Rosenberg, Chris Guitar: Cogan, Greg Piano: Spontaneous Group Vocal: The band The Vocal: Group Spontaneous Trombones: Matt Havilan, Earl McIntyre, Doug Purviance (bass) Purviance Doug McIntyre, Earl Havilan, Matt Trombones: Trombones: Herb Besson, Conrad Herwig, Larry Farrell, Matt Finders (bass) Finders Matt Farrell, Larry Herwig, Conrad Besson, Herb Trombones: Piano: Art Hirahara, Guitar: Vic Juris, Bass: Gene Perla, Drums: Scott Neumann Scott Drums: Perla, Gene Bass: Juris, Vic Guitar: Hirahara, Art Piano: Trumpets: Earl Gardner, Dean Pratt, Jeff Parke, Jerry Sokolov Jerry Parke, Jeff Pratt, Dean Gardner, Earl Trumpets: Trumpets: Lew Soloff (lead ),Bob Millikan, Jeff Parke, John Eckert John Parke, Jeff Millikan, ),Bob (lead Soloff Lew Trumpets: Trombones: Tim Sessions (lead), Charlie Gordon, Sam Burtis (bass) Burtis Sam Gordon, Charlie (lead), Sessions Tim Trombones: Woodwinds: Andy Fusco, Dan Block, Richie Perry (flute), Bob Hanlon: (clarinet), Tom Olin (bass clarinet) (bass Olin Tom (clarinet), Hanlon: Bob (flute), Perry Richie Block, Dan Fusco, Andy Woodwinds: Saxes: Andy Fusco, Walt Weiskopf (alto), Bob Hanlon, Richie Perry (tenor), Tom Olin (baritone) Olin Tom (tenor), Perry Richie Hanlon, Bob (alto), Weiskopf Walt Fusco, Andy Saxes: Trumpets: Jon Owens (lead), Bud Burridge, Colin Brigstocke, Darryl Shaw -

December 2016

Symphony Notes A publication of the Livermore-Amador Symphony and Guild Vol.54, No.1, December 2016 THE LIVERMORE-AMADOR SYMPHONY Arthur P. Barnes, Music Director Emeritus Presents A Heavenly Life Lara Webber, Music Director & Conductor Saturday, December 3, 2016, at 8:15 p.m. BANKHEAD THEATER, 2400 First Street, Livermore Livermore Performing Arts Center Doors open by 7:45 p.m. Exsultate, Jubilate W.A. Mozart Emily Helenbrook, soprano soloist –––––––– Intermission –––––––– Presentation of student awards Symphony No. 4 Gustav Mahler Emily Helenbrook, soprano soloist TICKET INFORMATION Tickets are available at the Bankhead ticket office. Contributions to the Symphony may also be given at the ticket office. In Person: Bankhead Theater Ticket Office, 2400 First Street, Livermore. Tuesday through Saturday, Noon to 6 p.m. Website: www.bankheadtheater.org Phone: 925-373-6800 Make checks payable to LVPAC. ♫ ♬ ♬ ♫ From the LAS Guild President This season started off with a bang on September 10 with no less than 3 outfit changes throughout the when the orchestra performed with Judy Collins as evening! [See Pops article on page 6.] the Bankhead Theater launched its 10th season gala The Pops Committee always welcomes thematic event, “Brilliance at the Bankhead.” It was a ideas for the next concert. If you have a theme wonderful evening! Ms. Collins expressed her suggestion for Pops 2017, and some song ideas to appreciation to the orchestra throughout the concert, back it up, we would greatly appreciate your input! and many LAS musicians shared that they thoroughly enjoyed the experience. I am really looking forward to seeing you all at the December 3 concert when soloist Emily Helenbrook Our annual Pops concert October 21, “POPS will perform in both the Mozart and Mahler pieces. -

Programmation Jazz À Vienne De 1980 À 2019

PROGRAMMATION JAZZ À VIENNE DE 1980 À 2019 SOMMAIRE 1980 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 1981 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 1982 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 1983 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 1984 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 1985 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 9 1986 .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 1987 ......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

MUSIC of the NIGHT Tonight Show’S Orchestra

JAN/FEB 2010 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM JAN/FEB 2010 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM or more than four decades, we’ve turned on TV late at night to see F talk-show hosts joking about the latest scandal and celebrities hawking their new films. But more discerning listeners know that when they tune in post- primetime, they’re also hearing some of the best musicians in the business—masters of precision who can tackle any genre and pick up the slightest cue. Since the halcyon days of Johnny Carson and Doc Severinsen’s Tonight Show band, house bands have punctuated hosts’ antics, musically introduced guests, played in and out of commercials and composed original scores for sketches—all in a night’s work. It’s time to shine a spotlight on the aces behind the music. PAUL SHAFFER AND Paul Shaffer and the CBS Orchestra THE CBS ORCHESTRA CBS/Late David Letterman Show With The Late Show With David Letterman to CBS in 1993. Shaffer initially resisted group jibed with not only the format of BANDLEADER: Paul Shaffer (keyboards) adding horns to the band, as it would affect Late Night With Conan O’Brien, but also CuRRENt LiNE-up: Anton Fig (percussion), Felicia Collins (guitar), Sid McGinnis (guitar), Will the versatility that became the quartet’s the emerging 1990s swing revival. And, Lee (bass), Tom Malone (trombone), Alan Chez hallmark. “Horns meant arrangements and as O’Brien had hoped, it recalled an older (trumpet/flugelhorn), Bruce Kapler (saxophone) more complex voicings,” he notes. “But the generation of late-night TV in both sound NotABLE foRmER mEmBERs: Steve Jordan, players I chose are masters of flexibility.” and look.