Schooled in Mass Murder 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31 School Shootings And/Or School-Related Acts of Violence Have

SCHOOL-RELATED ACTS OF VIOLENCE BY THOSE ON OR WITHDRAWING FROM PSYCHIATRIC DRUGS Between 1988 and Jan. 2013, there have been at least 31 school-related acts of violence committed by those taking or withdrawing from psychiatric drugs resulting in 162 wounded and 72 killed. (In other school shootings, information about their drug use was never made public— neither confirming or refuting if they were under the influence of prescribed drugs). 1. St. Louis, Missouri - January 15, 2013: 34-year-old Sean Johnson walked onto the Stevens Institute of Business & Arts campus and shot the school's financial aid director once in the chest, then shot himself in the torso. Johnson had been taking prescribed drugs for an undisclosed mental illness. 1 2. Snohomish County, Washington – October 24, 2011: A 15-year-old girl went to Snohomish High School where police alleged that she stabbed a girl as many as 25 times just before the start of school, and then stabbed another girl who tried to help her injured friend. Prior to the attack the girl had been taking “medication” and seeing a psychiatrist. Court documents said the girl was being treated for depression. 2 3. Myrtle Beach, South Carolina - September 21, 2011: 14-year-old Christian Helms had two pipe bombs in his backpack, when he shot and wounded Socastee High School’s “resource” (police) officer. However the officer was able to stop the student before he could do anything further. Helms had been taking drugs for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and depression. 3 4. Planoise, France - December 13, 2010: A 17-year-old youth held twenty pre-school children and their teacher hostage for hours at Charles Fourier preschool. -

Holding Parents Liable for the Acts of Their Adult Children, 22 Loy

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 22 Article 10 Issue 1 Fall 1990 1990 When Does Parental Liability End?: Holding Parents Liable for the Acts of Their Adult hiC ldren Joan Morgridge Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Joan Morgridge, When Does Parental Liability End?: Holding Parents Liable for the Acts of Their Adult Children, 22 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 335 (1990). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol22/iss1/10 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comment When Does Parental Liability End?: Holding Parents Liable for the Acts of Their Adult Children I. INTRODUCTION On May 20, 1988, Laurie Wasserman Dann entered a Winnetka, Illinois school and opened fire on a second grade classroom. She killed one child, Nicky Corwin, and injured five others. Laurie Dann left many questions unanswered when she killed herself later that day. One unanswered question, which was before the court in the case of Corwin v. Wasserman,' is whether parents can be held liable for the acts of their adult child. The Corwins contended that the Wassermans knew of their daughter's dangerous propensities. Specifically, it was alleged that the Wassermans knew that their daughter had made death threats, set fires, and was reported to have stabbed her ex-husband.2 The Corwins also asserted that the Wassermans controlled every aspect of Laurie Dann's life. -

Lifelong Learning GO Seniors, Retirees Are Students and Teachers in Peer Program Classes.Page 4

o ]IILES HERALD- SPECTATOR; S1.50 Thursday, October 19, 2017 nilesheraldspectator.com Lifelong Learning GO Seniors, retirees are students and teachers in peer program classes.Page 4 GOODMAN THEATRE = Can't-miss plays Local actors, playwrights and directors share the Chicago-area play they're most excited about this season. Page 19 OPINION Big Brother tried to come for your soda Columnist Randy Blaser says Cook Coun- ty's just-repealed soda tax was wrong- headed and unfair. Page 15 MIKE ISAACS/PIONEER PRESS Skokie resident Mick Jackson. left, talks about the health care system in the United States during a class Sept. 28 at National Louis University's Lifelong Learning Institute in Skokie. In the program, area seniors get opportunities to learn from each other. SPORTS LIVING Helping others Several Chicago businesses came together recently to send supplies and relief to those who were impacted by Hurricane Harvey. Inside BRIAN O'MAHONEV/DAILY SOUTHTOWN The season's fInal swings Local teams wrap up high school golf pcKAMRs.wpMam season at state meet Page 40 SHOUT OUT NILES HERALD- SPECTATOR nilesheraldspectator.com Kevin Soballe, loves sci-fi, fantasy Former Skokie resident Kevin called Jeremy's Beach Shack Cafe. Jim Rotche, General Manager Soballe, now a Chicago resident It moved to Lincoln Park. Phil Junk, Suburban Editor who lives near Skokie and Lincol- Q-As a kid, what did you want John Puterbaugh, Pioneer Press Editor: nwood, recently visited the Emily to be when you grew up? 312-222-2337; jputerbaugh®tribpub.com Oaks Nature Center in his old A: I always wanted to own a Georgia Garvey, ManaginEditor hometown. -

A Timeline of School Shootings

A Timeline of School Shootings Compiled by Peter Langman, Ph.D. This is not a complete listing of all incidents of school violence, but rather a chronological list of the attacks contained in the database of www.schoolshooters.info. The primary focus here is on what were intended to be multi-victim attacks, whether or not multiple people were actually shot. In addition, not all attacks were school shootings. Some perpetrators committed violence with other means than firearms; other attacks did not occur at schools, but were committed by people who had recently been students. Date of attack Perpetrator School Location 20 June 1913 Heinz Schmidt St. Mary’s Catholic School Bremen, Germany 18 May 1927 Andrew Kehoe Bath Consolidated School Bath, Michigan 6 May 1940 Verlin Spencer South Pasadena School District South Pasadena, California 4 March 1961 Ove Andersson Kungälvs Allmänna Läroverk Kungälv, Sweden 11 June 1964 Walter Seifert Catholic Elementary School Cologne, Germany 1 August 1966 Charles Whitman University of Texas Austin, Texas 12 November 1966 Robert Smith Rose-Mar College of Beauty Mesa, Arizona 11 February 1970 Robert Cantor University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 11 November 1971 Larry Harmon Gonzaga University Spokane, Washington 28 May 1975 Michael Slobodian Centennial Secondary School Brampton, Canada 27 October 1975 Robert Poulin St. Pius X Ottawa, Canada 19 February 1976 Neil Liebeskind Computer Learning Center Los Angeles, California 12 July 1976 Edward Allaway University of California Fullerton, California 29 January 1979 Brenda Spencer Cleveland Elementary School San Diego, California 6 October 1979 Mark Houston University of South Carolina Columbia, South Carolina 17 April 1981 Leo Kelly, Jr. -

Active Shooter: Recommendations and Analysis for Risk Mitigation

. James P. O’Neill . Police Commissioner . John J. Miller . Deputy Commissioner of . Intelligence and . Counterterrorism ACTIVE SHOOTER James R. Waters RECOMMENDATIONS AND ANALYSIS Chief of Counterterrorism FOR RISK MITIGATION 2016 EDITION AS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CITY POLICE DEPARTMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................3 RECENT TRENDS ........................................................................................................................6 TRAINING & AWARENESS CHALLENGE RESPONSE .................................................................................... 6 THE TARGETING OF LAW ENFORCEMENT & MILITARY PERSONNEL: IMPLICATIONS FOR PRIVATE SECURITY ........ 7 ATTACKERS INSPIRED BY A RANGE OF IDEOLOGIES PROMOTING VIOLENCE ................................................... 8 SOCIAL MEDIA PROVIDES POTENTIAL INDICATORS, SUPPORTS RESPONSE .................................................... 9 THE POPULARITY OF HANDGUNS, RIFLES, AND BODY ARMOR NECESSITATES SPECIALIZED TRAINING .............. 10 BARRICADE AND HOSTAGE-TAKING REMAIN RARE OCCURRENCES IN ACTIVE SHOOTER EVENTS .................... 10 RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................................11 POLICY ......................................................................................................................................... -

In the Supreme Court of the United States ______♦______ARIE S

No. 15-133 In The Supreme Court of the United States _____________♦_____________ ARIE S. FRIEDMAN AND THE ILLINOIS STATE RIFLE ASSOCIATION, Petitioners, v. CITY OF HIGHLAND PARK, Respondent. _____________♦_____________ On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit _____________♦_____________ BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI _____________♦_____________ STEVEN M. ELROD CHRISTOPHER B. WILSON CHRISTOPHER J. MURDOCH Counsel of Record HART M. PASSMAN DAVID J. BURMAN HOLLAND & KNIGHT LLP PERKINS COIE LLP 131 S. Dearborn Street 131 S. Dearborn Street 30th Floor 17th Floor Chicago, Illinois 60603 Chicago, Illinois 60603 Telephone: (312) 263-3600 Telephone: (312) 324-8400 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Respondent August 28, 2015 LEGAL PRINTERS LLC, Washington DC ! 202-747-2400 ! legalprinters.com COUNTERSTATEMENT OF QUESTIONS PRESENTED Whether the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits a municipality from banning a narrow category of unusually dangerous weapons that have been used in a series of deadly mass shooting events? -i- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page COUNTERSTATEMENT OF QUESTIONS PRESENTED .......................................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... iii STATEMENT .............................................................. 1 ADDITIONAL FACTS FOR CONSIDERATION ...... 3 REASONS FOR DENYING THE PETITION ............ 7 I. The Decisions Below are Consistent with Heller and McDonald and the Lower Courts Continue to Work to Apply Those Decisions ................................................ 8 II. There is No Conflict Among the Circuit Courts ...................................... 10 A. The Seventh Circuit’s Decision is Consistent with Heller II ..................................... 11 B. The Decision Below is Consistent with the Ninth Circuit’s Decision Upholding a Ban on Large Capacity Magazines ................. -

School-Related Acts of Violence by Those on Or Withdrawing from Psychiatric Drugs

SCHOOL-RELATED ACTS OF VIOLENCE BY THOSE ON OR WITHDRAWING FROM PSYCHIATRIC DRUGS Between 1988 and Jan. 2013, there have been at least 31 school-related acts of violence committed by those taking or withdrawing from psychiatric drugs resulting in 162 wounded and 72 killed. (In other school shootings, information about their drug use was never made public— neither confirming or refuting if they were under the influence of prescribed drugs). 1. St. Louis, Missouri - January 15, 2013: 34-year-old Sean Johnson walked onto the Stevens Institute of Business & Arts campus and shot the school's financial aid director once in the chest, then shot himself in the torso. Johnson had been taking prescribed drugs for an undisclosed mental illness. 1 2. Snohomish County, Washington – October 24, 2011: A 15-year-old girl went to Snohomish High School where police alleged that she stabbed a girl as many as 25 times just before the start of school, and then stabbed another girl who tried to help her injured friend. Prior to the attack the girl had been taking “medication” and seeing a psychiatrist. Court documents said the girl was being treated for depression. 2 3. Myrtle Beach, South Carolina - September 21, 2011: 14-year-old Christian Helms had two pipe bombs in his backpack, when he shot and wounded Socastee High School’s “resource” (police) officer. However the officer was able to stop the student before he could do anything further. Helms had been taking drugs for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and depression. 3 4. Planoise, France - December 13, 2010: A 17-year-old youth held twenty pre-school children and their teacher hostage for hours at Charles Fourier preschool. -

Pretend Gun-Free School Zones: a Deadly Legal Fiction

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Connecticut Law Review School of Law 2009 Pretend Gun-Free School Zones: A Deadly Legal Fiction David B. Kopel Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review Recommended Citation Kopel, David B., "Pretend Gun-Free School Zones: A Deadly Legal Fiction" (2009). Connecticut Law Review. 52. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/52 CONNECTICUT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 42 DECEMBER 2009 NUMBER 2 Article Pretend “Gun-Free” School Zones: A Deadly Legal Fiction DAVID B. KOPEL Most states issue permits to carry a concealed handgun for lawful protection to an applicant who is over twenty-one years of age, and who passes a fingerprint-based background check and a safety class. These permits allow the person to carry a concealed defensive handgun almost everywhere in the state. Should professors, school teachers, or adult college and graduate students who have such permits be allowed to carry firearms on campus? In the last two years, many state legislatures have debated this topic. School boards, regents, and administrators are likewise faced with decisions about whether to change campus firearms policies. This Article is the first to provide a thorough analysis of the empirical evidence and policy arguments regarding licensed campus carry. Whether a reader agrees or disagrees with the Article’s policy recommendations, the Article can lay the foundation for a better-informed debate, and a more realistic analysis of the issue. 515 ARTICLE CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 517 II. THE LEGAL AND FACTUAL SETTING ............................................ 518 A. WHAT DOES THE CONSTITUTION REQUIRE? ....................................... 521 B. THE PUSH FOR CARRY RIGHTS ON CAMPUSES ................................... -

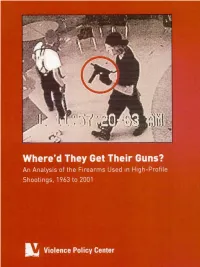

Where'd They Get Their Guns? an Analysis Of

Introduction On October 16, 1991, George Hennard drove his Ford Ranger through the plate- glass window of a crowded Luby’s cafeteria in Killeen, Texas. Armed with two legally purchased 9mm handguns—a Glock and a Ruger—Hennard climbed out of his pickup truck and proceeded to methodically gun down 23 of the restaurant’s patrons and employees. Wounded by police gunfire, he then ended his own life with the Glock pistol.a Ten years later, Hennard’s attack stands as America’s deadliest shooting. The Luby’s massacre marked the beginning of a decade that would leave as its legacy the palpable fear among Americans that no place outside the home is guaranteed safe. Restaurants, post offices, public transportation, and office buildings would soon be joined by schools, houses of worship, and day care centers as sites remembered for the suffering and death imposed by handguns. Mass-shooting victims comprise only a fraction of the thousands of Americans who die in gun homicides each year. Yet the effects of mass shootings are immeasurable. Day-in and day-out handgun shootings ending in the death of a single victim are routinely relegated to the back pages of local newspapers. While many Americans are able to dismiss the bulk of handgun deaths by viewing them through an “it can’t happen to me” prism colored by race, class, personal beliefs, or lack of information, it is the very randomness of mass shootings—that they can happen at any time, anywhere, and to anyone—that gives them such an inordinately powerful effect on the overall quality of our national life. -

ED417242.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 417 242 UD 032 182 AUTHOR Ethiel, Nancy, Ed. TITLE Saving Our Children: Can Youth Violence Be Prevented? An Interdisciplinary Conference (Wheaton, IL, May 20-22, 1996). INSTITUTION Harvard Univ., Cambridge, MA. Center for Criminal Justice. SPONS AGENCY McCormick Tribune Foundation, Chicago, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-88086-029-4 PUB DATE 1996-05-00 NOTE 90p. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Conferences; *Cost Effectiveness; High Schools; Inner City; Junior High Schools; Males; Minority Groups; *Prevention; Program Effectiveness; Program Evaluation; Sex Role; Social Problems; *Urban Youth; *Violence ABSTRACT Recognizing that violence is demographically concentrated in the male minority in inner cities is a necessary starting point for discussions of how to combat this violence. A conference on the prevention of youth violence was held in May 1996 to throw light on the problem of youth violence directly and specifically. Participants in this conference wanted to focus on prevention rather than enforcement, although there was no intent to disparage the importance of traditional law enforcement. The conference report in this volume begins by detailing trends in youth violence and the social conditions that underlie it. Then presentations that are reviewed evaluates the cost-effectiveness of specific programs to reduce violence and presentations that discussed personal experiences in implementing programs. The following sections summarize the messages of various conference presenters -

Laurie Dann's 1988 School Shooting Hit Close to Home

2 THE NEW TRIER EXAMINER New building’s modern style raises safety concerns The all glass design of the new building makes lockdown drills more complicated, limiting the spaces that students can be completely out of view and forcing some to evacuate their classrooms Kim so how are you supposed to hide?” she asked. safety concerns. Dubravec stated that both the police and Lockdowns in the new building In most lockdown situations, Principal Denise fire departments have reviewed safety procedure plans more complicated for students Dubravec urged students to “find a place inside the and have also been present in the building during all drills. building that is obscured from view unless you are While the school is able to secure the entire new and staff directed otherwise.” building relatively quickly, it is the glass-enclosed Concerns over the window design became more rooms that raise questions. In case of an emergency, the by Eleanor Kaplan and Alyssa Pak evident when the building opened. Looking at a floor doors between the new and old parts of the buildings are The many glass windows of the newly-completed plan and deciding where students could hide in case of automatically locked shut when a lockdown is initiated, West Wing building have raised safety concerns among a lockdown is much different than going into a physical with the goal of securing the entire new building. students after this year’s recent lockdown drills. room and seeing the options, noted Assistant Principal for Munley recently toured Vernon Hills High School According to Steve Linke, NT facilities manager Administrative Services, Gerry Munley. -

US School Shootings Data, 1979-2011

THE BULLY SOCIETY: U.S. School Shootings data, 1979-2011* Klein, Jessie, (2012) The Bully Society: school shootings and the crisis of bullying in America’s schools, New York, NY: NYU Press, http//:www.nyu-press.org/bullysociety/dataonschoolshootings.pdf. Please let us work together to build safer and more peaceful schools. - Jessie Klein Date/Place/ Name/Age Killed / Motives/Contributory Factors Warnings / Notes School Wounded January 29, Brenda Ann Killed: 1 Violence against girls/women: Brenda says she asked her 1979 Spencer, 16 principal, 1 Brenda claimed her violence grew father for a radio for her school out of an abusive home life in birthday, and he bought her a San Diego, custodian which her father beat and sexually gun. “I felt like he wanted California abused her.1 me to kill myself,” she said.3 Wounded: 8 Grover students, 1 Anti-school: Said that when she To explain the shooting, Cleveland police officer told school counselors about her Brenda said, “I don’t like Elementary home life, they ignored her.2 Mondays.” (Her words School became the popular lyrics in a song by the Irish Rock #1 Group Boomtown Rats, “I Don’t Like Mondays.”)4 October 6, 1979 Mark Houston, Killed: 2 Other: Police speculated that 19 students Mark was angry when the police Columbia, sent everyone home from a South Carolina Wounded: 5 fraternity party he had been at students previously; Mark was mad that he University of hadn’t received his $2.00 back; South Carolina the defense argued that he had brain damage from an early #2 childhood car accident.5 December 1979 Roger Cutsinger, Killed: 1 Dating/domestic violence: Roger 21 male student fatally shot his roommate and Seattle, lover, Larry Duerkson, hoping to Washington Wounded: 0 collect $500,000 from Larry’s life insurance policy.