The Roles of Insect Cocoons in Cold Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 10 • Principles of Conserving the Arctic's Biodiversity

Chapter 10 Principles of Conserving the Arctic’s Biodiversity Lead Author Michael B. Usher Contributing Authors Terry V.Callaghan, Grant Gilchrist, Bill Heal, Glenn P.Juday, Harald Loeng, Magdalena A. K. Muir, Pål Prestrud Contents Summary . .540 10.1. Introduction . .540 10.2. Conservation of arctic ecosystems and species . .543 10.2.1. Marine environments . .544 10.2.2. Freshwater environments . .546 10.2.3. Environments north of the treeline . .548 10.2.4. Boreal forest environments . .551 10.2.5. Human-modified habitats . .554 10.2.6. Conservation of arctic species . .556 10.2.7. Incorporating traditional knowledge . .558 10.2.8. Implications for biodiversity conservation . .559 10.3. Human impacts on the biodiversity of the Arctic . .560 10.3.1. Exploitation of populations . .560 10.3.2. Management of land and water . .562 10.3.3. Pollution . .564 10.3.4. Development pressures . .566 10.4. Effects of climate change on the biodiversity of the Arctic . .567 10.4.1. Changes in distribution ranges . .568 10.4.2. Changes in the extent of arctic habitats . .570 10.4.3. Changes in the abundance of arctic species . .571 10.4.4. Changes in genetic diversity . .572 10.4.5. Effects on migratory species and their management . .574 10.4.6. Effects caused by non-native species and their management .575 10.4.7. Effects on the management of protected areas . .577 10.4.8. Conserving the Arctic’s changing biodiversity . .579 10.5. Managing biodiversity conservation in a changing environment . .579 10.5.1. Documenting the current biodiversity . .580 10.5.2. -

Responses of Invertebrates to Temperature and Water Stress A

Author's Accepted Manuscript Responses of invertebrates to temperature and water stress: A polar perspective M.J. Everatt, P. Convey, J.S. Bale, M.R. Worland, S.A.L. Hayward www.elsevier.com/locate/jtherbio PII: S0306-4565(14)00071-0 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2014.05.004 Reference: TB1522 To appear in: Journal of Thermal Biology Received date: 21 August 2013 Revised date: 22 January 2014 Accepted date: 22 January 2014 Cite this article as: M.J. Everatt, P. Convey, J.S. Bale, M.R. Worland, S.A.L. Hayward, Responses of invertebrates to temperature and water stress: A polar perspective, Journal of Thermal Biology, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jther- bio.2014.05.004 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. 1 Responses of invertebrates to temperature and water 2 stress: A polar perspective 3 M. J. Everatta, P. Conveyb, c, d, J. S. Balea, M. R. Worlandb and S. A. L. 4 Haywarda* a 5 School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK b 6 British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, 7 Cambridge, CB3 0ET, UK 8 cNational Antarctic Research Center, IPS Building, University Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, 9 Malaysia 10 dGateway Antarctica, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand 11 12 *Corresponding author. -

Taxonomic Position and Status of Arctic <I>Gynaephora</I> and <I

PL-ISSN0015-5497(print),ISSN1734-9168(online) FoliaBiologica(Kraków),vol.63(2015),No4 Ó InstituteofSystematicsandEvolutionofAnimals,PAS,Kraków, 2015 doi:10.3409/fb63_4.257 TaxonomicPositionandStatusofArctic Gynaephora and Dicallomera Moths(Lepidoptera,Erebidae,Lymantriinae)* VladimirA.LUKHTANOV andOlgaA.KHRULEVA Accepted September 10, 2015 LUKHTANOV V.A., KHRULEVA O.A. 2015. Taxonomic position and status of arctic Gynaephora and Dicallomera moths (Lepidoptera, Erebidae, Lymantriinae). Folia Biologica (Kraków) 63: 257-261. We use analysis of mitochondrial DNA barcodes in combination with published data on morphology to rearrange the taxonomy of two arctic species, Gynaephora groenlandica and G. rossii. We demonstrate that (1) the taxon lugens Kozhanchikov, 1948 originally described as a distinct species is a subspecies of Gynaephora rossii, and (2) the taxon kusnezovi Lukhtanov et Khruliova, 1989 originally described as a distinct species in the genus Dicallomera isasubspeciesof Gynaephora groenlandica.Wealsoprovidethefirstevidence for the occurrence of G. groenlandica in the Palearctic region (Wrangel Island). Key words: COI, DNA barcode, Gynaephora, Dicallomera, Lymantriinae, polar environments. Vladimir A. LUKHTANOV, Department of Karyosystematics, Zoological Institute of Russian AcademyofSciences,Universitetskayanab.1,199034St.Petersburg, Russia;Departmentof Entomology, Faculty of Biology, St. Petersburg State University, Universitetskaya nab. 7/9, 199034 St. Petersburg, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Olga A. KHRULEVA, Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of Russian Academy of Sci- ences, Leninsky 33, Moscow 119071, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] The genera Gynaephora Hübner, 1819 and Di- 1835) and G. lugens Kozhanchikov, 1948, and one callomera Butler, 1881 belong to the subfamily representative of Dicallomera (D. kusnezovi Lukh- Lymantriinae of the family Erebidae (ZAHIRI et al. tanov et Khruliova, 1989) are known to be high 2012). -

INSECT: GYNAEPHORA GROENLANDICA / G. ROSSII Per Mølgaard and Dean Morewood

ITEX INSECT: GYNAEPHORA GROENLANDICA / G. ROSSII Per Mølgaard and Dean Morewood Woolly-bear caterpillars, Gynaephora groenlandica, are (Esper), is found in Europe but may not occur at tundra important predators on the leaf buds and young catkins of sites. The two North American species occur together at Salix spp. early in the season. Field observations have many sites in the Canadian Arctic and may be separated by shown a strong preference for Salix arctica, and for the the following characteristics. reproductive success as well as for vegetative growth of the willows, the number and activity of the caterpillars EGGS: Eggs themselves may be indistinguishable mor- may be of great importance. When present in the ITEX phologically; however, egg masses are often laid on co- plots, especially those with Salix spp., notes should be coons, which differ between the two species (see below). taken on the Salix sheets or on the sheets especially LARVAE: Because of their small size and their tendency designed for Gynaephora observations. to stayout of site, newly-hatched larvae are unlikely to be The life cycle of this moth is exceptional as it may encountered in the field unless found when they are still on take several years to develop from first instar larva to adult the cocoons where the eggs from which they hatched were insect. In Greenland, on Disko Island, outbreaks were seen laid. Older larvae may be separated according to the form in 1978 (Kristensen, pers. comm.) and again in 1992 and colour patterns of the larval hairs. Larvae of G. (Mølgaard pers. obs.), which indicates fluctuations with groenlandica have long hairs that range from dark brown peak populations with 14 years interval, which is similar to to golden yellow, depending on how recently they have the life cycle duration at Alexandra Fjord (Kukal and moulted, and have two distinct tufts of black followed by Kevan, 1987). -

Seasonality of Some Arctic Alaskan Chironomids

SEASONALITY OF SOME ARCTIC ALASKAN CHIRONOMIDS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Shane Dennis Braegelman In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Program: Environmental and Conservation Sciences December 2015 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title Seasonality of Some Arctic Alaskan Chironomids By Shane Dennis Braegelman The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Malcolm Butler Chair Kendra Greenlee Jason Harmon Daniel McEwen Approved: June 1 2016 Wendy Reed Date Department Chair ABSTRACT Arthropods, especially dipteran insects in the family Chironomidae (non-biting midges), are a primary prey resource for many vertebrate species on Alaska’s Arctic Coastal Plain. Midge-producing ponds on the ACP are experiencing climate warming that may alter insect seasonal availability. Chironomids display highly synchronous adult emergence, with most populations emerging from a given pond within a 3-5 day span and the bulk of the overall midge community emerging over a 3-4 week period. The podonomid midge Trichotanypus alaskensis Brundin is an abundant, univoltine, species in tundra ponds near Barrow, Alaska, with adults appearing early in the annual emergence sequence. To better understand regulation of chironomid emergence phenology, we conducted experiments on pre-emergence development of T. alaskensis at different temperatures, and monitored pre-emergence development of this species under field conditions. We compared chironomid community emergence from ponds at Barrow, Alaska in the 1970s with similar data from 2009-2013 to assess changes in emergence phenology. -

Fauna Europaea: Neuropterida (Raphidioptera, Megaloptera, Neuroptera)

Biodiversity Data Journal 3: e4830 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.3.e4830 Data Paper Fauna Europaea: Neuropterida (Raphidioptera, Megaloptera, Neuroptera) Ulrike Aspöck‡§, Horst Aspöck , Agostino Letardi|, Yde de Jong ¶,# ‡ Natural History Museum Vienna, 2nd Zoological Department, Burgring 7, 1010, Vienna, Austria § Institute of Specific Prophylaxis and Tropical Medicine, Medical Parasitology, Medical University (MUW), Kinderspitalgasse 15, 1090, Vienna, Austria | ENEA, Technical Unit for Sustainable Development and Agro-industrial innovation, Sustainable Management of Agricultural Ecosystems Laboratory, Rome, Italy ¶ University of Amsterdam - Faculty of Science, Amsterdam, Netherlands # University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland Corresponding author: Ulrike Aspöck ([email protected]), Horst Aspöck (horst.aspoeck@meduni wien.ac.at), Agostino Letardi ([email protected]), Yde de Jong ([email protected]) Academic editor: Benjamin Price Received: 06 Mar 2015 | Accepted: 24 Mar 2015 | Published: 17 Apr 2015 Citation: Aspöck U, Aspöck H, Letardi A, de Jong Y (2015) Fauna Europaea: Neuropterida (Raphidioptera, Megaloptera, Neuroptera). Biodiversity Data Journal 3: e4830. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.3.e4830 Abstract Fauna Europaea provides a public web-service with an index of scientific names of all living European land and freshwater animals, their geographical distribution at country level (up to the Urals, excluding the Caucasus region), and some additional information. The Fauna Europaea project covers about 230,000 taxonomic names, including 130,000 accepted species and 14,000 accepted subspecies, which is much more than the originally projected number of 100,000 species. This represents a huge effort by more than 400 contributing specialists throughout Europe and is a unique (standard) reference suitable for many users in science, government, industry, nature conservation and education. -

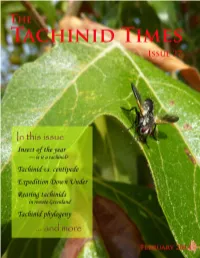

The Tachinid Times February 2014, Issue 27 INSTRUCTIONS to AUTHORS Chief Editor James E

Table of Contents Articles Studying tachinids at the top of the world. Notes on the tachinids of Northeast Greenland 4 by T. Roslin, J.E. O’Hara, G. Várkonyi and H.K. Wirta 11 Progress towards a molecular phylogeny of Tachinidae, year two by I.S. Winkler, J.O. Stireman III, J.K. Moulton, J.E. O’Hara, P. Cerretti and J.D. Blaschke On the biology of Loewia foeda (Meigen) (Diptera: Tachinidae) 15 by H. Haraldseide and H.-P. Tschorsnig 20 Chasing tachinids ‘Down Under’. Expeditions of the Phylogeny of World Tachinidae Project. Part II. Eastern Australia by J.E. O’Hara, P. Cerretti, J.O. Stireman III and I.S. Winkler A new range extension for Erythromelana distincta Inclan (Tachinidae) 32 by D.J. Inclan New tachinid records for the United States and Canada 34 by J.E. O’Hara 41 Announcement 42 Tachinid Bibliography 47 Mailing List Issue 27, 2014 The Tachinid Times February 2014, Issue 27 INSTRUCTIONS TO AUTHORS Chief Editor JAMES E. O'HARA This newsletter accepts submissions on all aspects of tach- inid biology and systematics. It is intentionally maintained as a InDesign Editor OMBOR MITRA non-peer-reviewed publication so as not to relinquish its status as Staff JUST US a venue for those who wish to share information about tachinids in an informal medium. All submissions are subjected to careful editing and some are (informally) reviewed if the content is thought ISSN 1925-3435 (Print) to need another opinion. Some submissions are rejected because ISSN 1925-3443 (Online) they are poorly prepared, not well illustrated, or excruciatingly bor- ing. -

97 on the Occurrence of Nineta Pallida (Schneider

Entomologist’s Rec. J. Var. 126 (2014) 97 ON THE OCCURRENCE OF NINETA PALLIDA (SCHNEIDER, 1846) AND N. INPUNCTATA (REUTER, 1894) IN THE BRITISH ISLES AND REMARKS ON THESE RARE GREEN LACEWINGS (NEU.: CHRYSOPIDAE) 1 MICHEL CANARd, 2 dAVE WILTON ANd 3 COLIN W. PLANT 1 47 chemin Flou de Rious, F-31400 Toulouse, France (e-mail: [email protected]) 2 25 Burnham Road, Westcott, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, HP18 0PL, UK (e-mail: [email protected]) 3 14 West Road, Bishops Stortford, Hertfordshire CM23 3QP, UK (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract A third record of the green lacewing Nineta pallida (Schneider, 1846) is reported for Britain. A published record of Nineta inpunctata (Reuter, 1894) is shown to be an error, leaving only one valid British Isles record for that species. The opportunity is taken to discuss distribution, status and ecology of these two rare lacewings in Britain and France. Key words. Neuroptera, Chrysopidae, Nineta pallida, Nineta inpunctata, morphology, distribution, life cycle, univoltinism, photoperiod sensitivity. Nouvelles données sur la présence de Nineta pallida (Schneider, 1846) et de Nineta inpunctata (Reuter, 1894) dans les îles britanniques et remarques sur ces rares chrysopes (Neu.: Chrysopidae). Résumé Un troisième enregistrement de la chrysope verte Nineta pallida (Schneider, 1846) est signalé pour la Grande-Bretagne. Un compte rendu publié de Nineta inpunctata (Reuter, 1894) est une erreur, laissant seulement un enregistrement valide pour les îles britanniques de cette espèce. L’occasion est saisie pour discuter de la distribution, du statut et de l’écologie de ces deux chrysopes rares en Grande-Bretagne et en France. -

Of Licenced Research Northwest Territories

' ·· I I I J 1 T J Index of Licenced Research II Northwest Territories • j '\I 1985 { J j Science Advisor J P.o. Box 1617 I Government of the Northwest Territories J ~ - I January 1986 Q 179.98 .C66 1985 copy2 I. -] INTRODUCTION l Scientific Research Licenses are mandatory for all research conducted in the N.W.T. There are three categories. Wildlife Research is licensed by the Department of Renewable Resources, J Archaeology is licensed by the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre and all other research is licensed by the Science Advisor under the Scientists Act. A description of the procedures is J appended to the Index. l During the 1985 calendar year 260 li'cences to carry out scientific research were issued to scientists. Ninety-four 1985 licences were 1 issued to scientists directly affiliated with educational institutions. Of these 94 licences, 79 were issued to scientists from Canadian universities, 13 to scientists from U.S. universities, and 2 to scientists from other foreign universities. Of the 79 licences J granted to scientists from Canadian universities: Ontario received ............. 40 0 A1 berta received ..•..•.... , . 13 Quebec recetved . • . • . 9 Bri'tish Columbia received .... l Manitoba received ............ 5 J Newfoundland received ....•..• 3 J Saskatchewan received ..•..... 2 J The. i.ndex of 1 icenced research gi-ves the followi.ng information on each project: licence number, name and address of affi.liation of 1icen~ee. objective of the research and its location. I.t should be noted that i.nves ti,gators are ob'l i gated by the Ordinance to supply a report to the Commissi.oner withtn a stated ti"me. -

Lacewing News

Lacewing News NEWSLETTER OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF NEUROPTEROLOGY No. 16 Spring 2013 Presentation From David Penney th Hi all! Here’s the 16 issue of Lacewing News. THE FOSSIL NEUROPTERA BOOK Leitmotiv of this issue is “old, fond memories”: GAUNTLET HAS BEEN PICKED UP so, a lot of photos and dear moments! I hope you will enjoy them, Thank to all colleagues who send photos, messages and contributions. Please, don’t forget this is not a “formal” gazette, nor an official instruments of IAN, but only a “open space” to disseminate information, cues, jokes through the neuropterological community. So don’t hesitate to send me any suggestions, ideas, proposal, information, for the next issue! Please send all communications concerning Lacewing News to [email protected] (Agostino Letardi). Questions about the International Association of Neuropterology may be addressed to our current president, Dr. In Lacewing News 15 I proposed the idea of a Michael Ohl ([email protected]), who book on Fossil Neuroptera. The gauntlet was is also the organizer of next XII International picked up and this work is now in progress as Symposium on Neuropterology (Berlin 2014). part of the Siri Scientific Press Monograph Ciao! Series (email for ordering information or visit http://www.siriscientificpress.co.uk), with an expected publication date of 2014. The authors will be James E. Jepson (currently National Museum of Wales), Alexander Khramov (Paleontological Institute Moscow) and David Penney (University of Manchester). The draft cover shows a particularly nice example of the extinct family Kalligrammatidae. We already have lots of nice fossil images (both amber and rock) for this volume, but if any of you have access to well preserved fossils or hold the copyright of such images and would like to see them published in this volume, then we would be very happy to receive high resolution images in jpeg format. -

Species Catalog of the Neuroptera, Megaloptera, and Raphidioptera Of

http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, 4th series. San Francisco,California Academy of Sciences. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/3943 4th ser. v. 50 (1997-1998): http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/53426 Page(s): Page 39, Page 40, Page 41, Page 42, Page 43, Page 44, Page 45, Page 46, Page 47, Page 48, Page 49, Page 50, Page 51, Page 52, Page 53, Page 54, Page 55, Page 56, Page 57, Page 58, Page 59, Page 60, Page 61, Page 62, Page 63, Page 64, Page 65, Page 66, Page 67, Page 68, Page 69, Page 70, Page 71, Page 72, Page 73, Page 74, Page 75, Page 76, Page 77, Page 78, Page 79, Page 80, Page 81, Page 82, Page 83, Page 84, Page 85, Page 86, Page 87 Contributed by: MBLWHOI Library Sponsored by: MBLWHOI Library Generated 10 January 2011 12:00 AM http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/pdf3/005378400053426 This page intentionally left blank. The following text is generated from uncorrected OCR. [Begin Page: Page 39] PROCEEDINGS OF THE CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Vol. 50, No. 3, pp. 39-114. December 9, 1997 SPECIES CATALOG OF THE NEUROPTERA, MEGALOPTERA, AND RAPHIDIOPTERA OF AMERICA NORTH OF MEXICO By 'itutio. Norman D. Penny "EC 2 Department of Entomology, California Academy of Sciences San Francisco, CA 941 18 8 1997 Wooas Hole, MA Q254S Phillip A. Adams California State University, Fullerton, CA 92634 and Lionel A. Stange Florida Department of Agriculture, Gainesville, FL 32602 The 399 currently recognized valid species of the orders Neuroptera, Megaloptera, and Raphidioptera that are known to occur in America north of Mexico are listed and full synonymies given. -

Animals Information the Arctic Has Many Large Land Animals

Animals information The Arctic has many large land animals including reindeer, musk ox, lemmings, arctic hares, arctic terns, snowy owls, squirrels, arctic fox and polar bears. As the Arctic is a part of the land masses of Europe, North America and Asia, these animals can migrate south in the winter and head back to the north again in the more productive summer months. There are a lot of these animals in total because the Arctic is so big. The land isn't so productive however so large concentrations are very rare and predators tend to have very large ranges in order to be able to get enough to eat in the longer term. There are also many kinds of large marine animals such as walrus and seals such as the bearded, harp, ringed, spotted and hooded. Narwhals and other whales are present but not as plentiful as they were in pre-whaling days. The largest land animal in the Antarctic is an insect, a wingless midge, Belgica antarctica, less than 1.3cm (0.5in) long. There are no flying insects (they'd get blown away). There are however a great many animals that feed in the sea though come onto the land for part or most of their lives, these include huge numbers of adelie, chinstrap, gentoo, king, emperor, rockhopper and macaroni penguins. Fur, leopard, Weddell, elephant and crabeater seals (crabeater seals are the second most populous large mammal on the planet after man) and many other kinds of birds such as albatrosses and assorted petrels. There are places in Antarctica where the wildlife reaches incredible densities, the more so for not suffering any human hunting.