Guildford and Hogs Back Geowalk, Surrey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LTN Winter 2021 Newsletter

THE LUTYENS TRUST To protect and promote the spirit and substance of the work of Sir Edwin Lutyens O.M. NEWSLETTER WINTER 2021 A REVIEW OF NEW BOOK ARTS & CRAFTS CHURCHES BY ALEC HAMILTON By Ashley Courtney It’s hard to believe this is the first book devoted to Arts and Crafts churches in the UK, but then perhaps a definition of these isn’t easy, making them hard to categorise? Alec Hamilton’s book, published by Lund Humphries – whose cover features a glorious image of St Andrew’s Church in Sunderland, of 1905 to 1907, designed by Albert Randall Wells and Edward Schroeder Prior – is split into two parts. The first, comprising an introduction and three chapters, attempts a definition, placing this genre in its architectural, social and religious contexts, circa 1900. The second, larger section divides the UK into 14 regions, and shows the best examples in each one; it also includes useful vignettes on artists and architects of importance. For the author, there is no hard- and-fast definition of an Arts and Crafts church, but he makes several attempts, including one that states: “It has to be built in or after 1884, the founding date of the Art Workers’ Guild”. He does get into a bit of a pickle, however, but bear with it as there is much to learn. For example, I did not know about the splintering of established religion, the Church of England, into a multitude of Nonconformist explorations. Added to that were the social missions whose goal was to improve the lot of the impoverished; here social space and church overlapped and adherents of the missions, such as CR Ashbee, taught Arts and Crafts skills. -

Su103 Box Hill from Westhumble

0 Miles 1 2 su103 Box Hill from Westhumble 0 Kilometres 1 2 3 The Burford Bridge roundabout is on the The walk shown is for guidance only and should With thanks to Dean Woodrow A24 between Dorking and Leatherhead not be attempted without suitable maps. Details 3 Go W (right) up the road for 200m and then 5 Go NW (left) across the grass to reach a SE on a signed path that descends through a road and then W (left) on the road to go N Distance: 11km (7 miles) field, a wood and a 2nd field to reach a road. pass the car park and NT Shop. At a '1.5T' Total Ascent: 340m (1115ft) Go E (left) on the road past the remains of road sign go NW (left) past Box Hill Fort to Time: 31/2 hrs Grade: 4 Westhumble Chapel to reach a crossroads. Go descend a bridleway to a fork. Go NW (left) to Maps: OS Landranger® 187 SE on Adlers Lane and continue SE at a join a 2nd path that descends across the or OS Explorer Map™ 146 junction. At a crossing path go S (right) on a grass. After 200m fork (W) left on a faint path Start/Finish: Burford Bridge Car Park footpath (signed 'Dorking') to reach a 2nd to descend more steeply. Continue through a A24 S of Mickleham, Surrey crossing path - The North Downs Way (NDW). small wood to reach a road opposite the car 1 Grid Ref: TQ172521 (1 /2 km) park and the start. (2km) Sat Nav: N51.2560 W0.3227 4 Go E (left) on the NDW to pass under the railway and then cross the A24. -

Item D1 Creation of Two New Sections of Road As Dedicated Bus Rapid Transit Route for Buses, Cyclists and Pedestrians Only

SECTION D DEVELOPMENT TO BE CARRIED OUT BY THE COUNTY COUNCIL Background Documents: the deposited documents; views and representations received as referred to in the reports and included in the development proposals dossier for each case; and other documents as might be additionally indicated. Item D1 Creation of two new sections of road as dedicated Bus Rapid Transit route for buses, cyclists and pedestrians only. Section 1 - New road, 1km in length, connecting Whitfield Urban Expansion to Tesco roundabout at Honeywood Parkway via new overbridge over A2. Access to bridge will be controlled by bus gates. Section 2 - New road, 1.1km in length, connecting B & Q roundabout on Honeywood Parkway to Dover Road, near Frith Farm, with access to Dover Road controlled by a bus gate. Providing access to future phases of White Cliffs Business Park at Dover Fastrack - Land to the north of Dover and to the south of Whitfield, Kent – DOV/20/01048 (KCC/DO/0178/2020) A report by Head of Planning Applications Group to Planning Applications Committee on 13th January 2021. Application by Kent County Council for Creation of two new sections of road as dedicated Bus Rapid Transit route for buses, cyclists and pedestrians only. Section 1 - New road, 1km in length, connecting Whitfield Urban Expansion to Tesco roundabout at Honeywood Parkway via new overbridge over A2. Access to bridge will be controlled by bus gates. Section 2 - New road, 1.1km in length, connecting B & Q roundabout on Honeywood Parkway to Dover Road, near Frith Farm, with access to Dover Road controlled by a bus gate. -

Bramley Conservation Area Appraisal

This Appraisal was adopted by Waverley Borough Council as a Supplementary Planning Document On 19th July 2005 Contents 1. Introduction 2. The Aim of the Appraisal 3. Where is the Bramley Conservation Area? 4. Threats to the Conservation area 5. Location and Population 6. History, Links with Historic Personalities and Archaeology 7. The Setting and Street Scene 8. Land Uses • Shops • Businesses • Houses • Open Spaces Park Lodge 9. Development in the Conservation area 10. Building Materials 11. Listed and Locally Listed Buildings 12. Heritage Features 13. Trees, Hedges and Walls 14. Movement, Parking and Footpaths 15. Enhancement Schemes 16. Proposed Boundary Changes 17. The Way Forward Appendices 1. Local Plan policies incorporated into the Local Development Framework 2. Listed Buildings 3. Locally Listed Buildings 4. Heritage Features 1. Introduction High Street, Bramley 1. Introduction 1.1. The legislation on conservation areas was introduced in 1967 with the Civic Amenities Act and on 26th March 1974 Surrey County Council designated the Bramley conservation area. The current legislation is the Planning (Listed Building and Conservation Areas) Act 1990, which states that every Local Authority shall: 1.2. “From time to time determine which parts of their area are areas of special architectural or historic interest the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance, and shall designate those areas as conservation areas.” (Section 69(a) and (b).) 1.3. The Act also requires local authorities to “formulate and publish proposals for the preservation and enhancement of conservation areas…………”.(Section 71). 1.4. There has been an ongoing programme of enhancement schemes in the Borough since the mid 1970s. -

Inwood Manor Wanborouch • Surrey

INWOOD MANOR Wanborouch • Surrey INWOOD MANOR Wanborough • Surrey Georgian style country house with land and glorious views Guildford: 5.2 miles, Farnham: 5.4 miles, M25: 13 miles, Heathrow Airport: 31 miles, Gatwick Airport: 31 miles, Central London: 36 miles (all mileages approximate) = Reception hall, drawing room, dining room, library/media room and family room Kitchen/breakfast room, utility room, boot room and cloakroom Master suite and guest suite 6 further bedrooms and 3 further bath/shower rooms Triple garage with canopy link to house Greenhouse Formal gardens, orchard and paddocks In about 8 acres Savills Guildford 244-246 High Street, Guildford, Surrey GU1 3JF [email protected] 01483 796820 DIRECTIONS The area benefits from excellent communications via the A31 and the A3 (London – Portsmouth). From Guildford, follow the A31, Farnham Road from Guildford centre for 5.8 miles, along the Hogs The A3 connects at Wisley with the M25 for the airports and the national motorway network. Back, and then take the right hand slip road, signed to Ash and Ash Green and turn right, back onto Guildford station provides a fast and frequent service to London Waterloo, with journey times from the A31, towards Guildford on the east-bound carriageway. In precisely 0.8 miles, the turning onto about 35 minutes. Farnham station also provides a service to London Waterloo with journey times Inwood Lane will be seen, with a red letter box at the side and signed ‘Inwood’. Follow this lane and from under an hour. bear right at the fork onto a drive leading to the Inwood Manor. -

And the Optohedron Silent Pool, St Martha's Hill

A 6 mile scenic walk around a popular on natural geometry and includes three immediately right onto stone track signed fence line, fork right between old gate kaleidoscopic elements. Following your NDW, passing cottage on your right. posts to join narrower path into trees and area on the North rest stop, head back to the NDW to Soon after fence ends on your right, you scrub. Downs Way in the continue until you emerge alongside a will pick up next POT waymarker. Stay Stay with path as it leads steadily Surrey Hills Area vehicle barrier and junction with A25. with this path leading to major junction, downhill and then steeper to reach Cross over this very busy road with care marked with a couple of waymarker of Outstanding junction with sunken lane, Water Lane. Natural Beauty and enjoy the spectacular views for which posts. Turn right here to join permissive Newlands Corner is well-known. Follow horse ride, marked as POT. Follow main 5 WATER LANE TO END OF WALK Nestling in a hollow at the stone path to car park. Bear left and walk obvious path and as you pick up next Turn left and then immediately right foot of the North Downs, length of car park to end, passing toilets waymarker post, stay with POT bearing Sherbourne Pond & Silent to join stone access public bridleway. and visitor centre to right. left heading uphill to reach T-junction. Pool are fed by springs. After passing house on right, keep Turn right and you will pass a stone Part of St Martha’s church 2 NEWLANDS CORNER TO directly ahead alongside gate and follow boundary marker dated 1933. -

YOUR UNIVERSITY SURREY.AC.UK 3 Welcome Community News

Spring 2017 News from the University of Surrey for Guildford residents SURREY.AC.UK UNIVERSITYOFSURREY UNIOFSURREY Your invitation to WON DER 13 May 2017 11am - 5pm University of Surrey, Guildford Please register via: surrey.ac.uk/festivalofwonder MUSIC · FOOD · TALKS · SPORT · DISCOVERY · WONDER Incorporating FREE Penelope Keith, DBE Community Reps scheme Festival ofFEST Wonder Spring on campus Guest Editor p2 Your view counts p5 Celebrating 50 years p11 Meet the team p12 2. The University’s 50th Anniversary celebrations 1. Waving flags on Guildford High Street 2. Mayor of Guildford, Councillor Gordon Jackson (left) and Vice-Chancellor, Professor Max Lu (right) 3. Folarin Oyeleye (left) and Tamsey Baker (right) 1. 3. Celebrating 50 years at home in Guildford The bells of Guildford Cathedral rang out on 9 September 2016 to mark the beginning of the University of Surrey’s 50th Anniversary year, celebrating half a century of calling Guildford ‘home’. The University’s Royal the cobbles of Guildford In the 50 years since setting Residents of Guildford and Charter was signed in 1966, High Street, adorned with up home on Stag Hill, the surrounding area are establishing the University banners and brought to the University has been warmly invited to join the in Guildford from its roots in life by the waving of blue warmly welcomed as part University as it ends its 50th Battersea, London. Exactly and gold flags, and made of the local community Anniversary celebrations 50 years later, bells pealed their way up to Holy in Guildford. Its staff and with a bang, in the form of across Battersea and ended Trinity Church. -

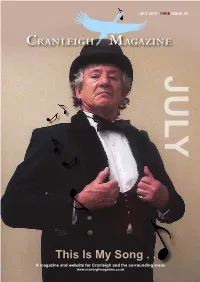

This Is My Song

CRANLEIGH MAGAZINE JULY 2019 - FREE ISSUE 45 JULY This Is My Song . A magazine and website for Cranleigh and the surrounding areas www.cranleighmagazine.co.uk CRANLEIGHTHE MAGAZINE BIG SALE EX DISPLAY ITEMS AT HALF PRICE OR LESS! £1199.00 £599.50 £529.00 £679.00 £249.50 £299.50 LESS THAN ½ PRICE ½ PRICE LESS THAN ½ PRICE Introducing Leighwood Fields, a stunning £749.00 £349.00 £1149.00 new development of 3, 4 and 5 bedroom £374.50 £149.50 £574.50 homes, exquisitely designed and crafted to the highest quality. Nestled in the heart of ½ PRICE LESS THAN ½ PRICE ½ PRICE rural Surrey, Leighwood Fields is moments from the centre of Cranleigh and offers the £1819.00 quintessential country lifestyle. £899.50 3, 4 & 5 bedroom homes from £575,000* £1599.00 £489.00 £799.50 £199.50 To book an appointment please call 01483 355 429 or visit leighwoodfields.co.uk LESS THAN ½ PRICE ½ PRICE LESS THAN ½ PRICE Sales & Marketing Suite, open daily 10am-5pm EVERY ITEM IN STORE Knowle Lane, Cranleigh, Surrey GU6 8RF *Prices and details correct at time of going to press. REDUCED! Photography depicts streetscene and Showhome and is indicative only. CRANLEIGH FURNITURE www.leighwoodfields.co.uk www.cranleighfurniture.co.uk 01483 271236 264, HIGH STREET, CRANLEIGH, GU6 8RT 2 Introducing Leighwood Fields, a stunning new development of 3, 4 and 5 bedroom homes, exquisitely designed and crafted to the highest quality. Nestled in the heart of rural Surrey, Leighwood Fields is moments from the centre of Cranleigh and offers the quintessential country lifestyle. 3, 4 & 5 bedroom homes from £575,000* To book an appointment please call 01483 355 429 or visit leighwoodfields.co.uk Sales & Marketing Suite, open daily 10am-5pm Knowle Lane, Cranleigh, Surrey GU6 8RF *Prices and details correct at time of going to press. -

The Planning Group

THE PLANNING GROUP Report on the letters the group has written to Guildford Borough Council about planning applications which we considered during the period 1 January to 30 June 2020 During this period the Planning Group consisted of Alistair Smith, John Baylis, Amanda Mullarkey, John Harrison, David Ogilvie, Peter Coleman and John Wood. In addition Ian Macpherson has been invaluable as a corresponding member. Abbreviations: AONB: Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty AGLV: Area of Great Landscape Value GBC: Guildford Borough Council HTAG: Holy Trinity Amenity Group LBC: Listed Building Consent NPPF: National Planning Policy Framework SANG: Suitable Alternative Natural Greenspace SPG: Supplementary Planning Guidance In view of the Covid 19 pandemic the Planning Group has not been able to meet every three weeks at the GBC offices. We have, therefore, been conducting meetings on Zoom which means the time taken to consider each of the applications we have looked at has increased. In addition, this six month period under review has been the busiest for the group for four years and thus the workload has inevitably increased significantly. During the period there were a potential 993 planning applications we could have looked at. We sifted through these applications and considered in detail 89 of them. The Group wrote 41 letters to the Head of Planning Services on a wide range of individual planning applications. Of those applications 13 were approved as submitted; 8 were approved after amending plans were received and those plans usually took our concerns into account; 5 were withdrawn; 10 were refused; and, at the time of writing, 5 applications had not been decided. -

WOLDINGHAM COUNTRYSIDE WALK Along Path

The SURREY HILLS was one of the first landscapes THE NORTH DOWNS WAY is a national trail TRAVEL INFORMATION in the country to be designated an Area of Outstanding which follows the chalk scarp of the North Downs There is a frequent Southern Railway service Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1958. It is now one of 38 for 153 miles from Farnham to Canterbury and from London Victoria to Woldingham station. AONBs in England and Wales and has equal status in Dover, passing 8 castles and 3 cathedrals. To find Travel time is approximately 30 minutes. planning terms to a National Park. The Surrey Hills out more please visit www.nationaltrail.co.uk AONB stretches across rural Surrey, covering a quarter For train times, fares and general rail information of the county. THE NATIONAL TRUST manages land on the scarp edge at Hanging Wood and South Hawke please contact National Rail Enquiries on For further information on the 03457 484950. Surrey Hills please visit including woodland, scrub, and chalk grassland. www.surreyhills.org The Trust, a charitable organisation, acquires areas principally for conservation and landscape and has For more information about Southern Railway a policy of open access to the public. Please visit please visit www.southernrailway.com. www.nationaltrust.org.uk for further information. For information on bus routes that serve THE WOODLAND TRUST a charity founded Woldingham station please visit in 1972, is concerned with the conservation of www.surreycc.gov.uk. Britain's woodland heritage. Its objectives are to To East Croydon conserve, restore and re-establish trees, plants and & London wildlife, and to facilitate public access. -

Brooklands Farm CRANLEIGH SURREY

Brooklands Farm CRANLEIGH SURREY Brooklands Farm CRANLEIGH SURREY Beautifully refurbished country house and a magnificent barn in a truly rural setting Main House Reception hall • Drawing room • Dining room • Sitting room • Study • Playroom Kitchen/breakfast room • Utility room 2 WCs Master bedroom suite with dressing room and his and hers bathrooms Two further double bedrooms with en suite bathrooms • Three further bedrooms • 1 further family bathroom The Barn Vaulted sitting room Family room Kitchen/Breakfast room WC Two bedrooms with en suite bathrooms Indoor swimming pool complex with Turkish bath, changing and shower room Garaging for multiple cars • Stabling • Well maintained gardens, grounds, paddocks and woodland In all about 16.78 acres Approximate Gross Internal Area 5738 sq ft / 533.1 sq m Approximate Gross Internal Area Outbuildings 5296 sq ft / 492.0 sq m Total 11,034 sq ft /1,025.1sq m Knight Frank LLP Knight Frank LLP 2-3 Eastgate Court, High Street, 55 Baker Street, Guildford, Surrey GU1 3DE London W1U 8AN Tel: +44 1483 565 171 Tel: +44 20 7861 5390 [email protected] [email protected] www.knightfrank.co.uk These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the brochure. Situation (All distances and times are approximate) Cranleigh – 2.5 miles S Guildford – 12 miles Godalming – 12 miles Central London – 43 miles T Guildford to London Waterloo (from 35 minutes) London Gatwick 23 miles -

Surrey Hills Aonb Areas of Search

CONFIDENTIAL SURREY COUNTY COUNCIL LCA PHASE 2 SURREY HILLS AONB AREAS OF SEARCH NATURAL BEAUTY EVALUATION by Hankinson Duckett Associates HDA ref: 595.1 October 2013 hankinson duckett associates t 01491 838175 f 01491 838997 e [email protected] w www.hda-enviro.co.uk The Stables, Howbery Park, Benson Lane, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, OX10 8BA Hankinson Duckett Associates Limited Registered in England & Wales 3462810 Registered Office: The Stables, Howbery Park, Benson Lane, Wallingford, OX10 8BA CONTENTS Page 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Assessment Background ............................................................................................................. 1 Table 1: LCA Landscape Types and Character Areas ...................................................................................... 2 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 5 4 Guidance ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Table 2: Natural England Guidance Factors and Sub-factors ........................................................................... 6 4.5 Application of the Guidance ............................................................................................................................. 10 5 The Surrey Hills Landscape