Our Scully History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soils of Chatham Island (Rekohu)

Soils of Chatham Island (Rekohu) Fronlis icce: 11nproved pastures Tiki larolin phase, on clay, strongly rollink near uitand tminshil’ NEW ZEALAND DEPARTMENT OF SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH N. H. TAYLOR Director SOIL BUREAU BULLETIN 19 SOILS OF CHATHAM ISLAND (REKOHU) By A. C. S. WRIGHT Soil Bureau 1959 Price: Paper cover, 15s. Quarter cloth, 20s. N.g. Soil Bur. Bull. 19. 60 pp. 22 figs, 5 tables R. E. OWEN. GOVERNMENT PRINTER. WELLINCTON. NEW ZEALAND -lm CONTENTS Page Introduction 7 .. .. Soils 10 The Pattern of the .. .. 16 Factors Concerned in Development of the Soil Pattern the .. 16 Geology .. 20 Climate .. 22 Flora Fauna and .. .. Soil Pattern 29 Historical Factors Causing Modification of the .. .. Pedological Significance of Soil Pattern 31 the .. .. Agricultural Significance of Soil Pattern 32 the . Elsewhere 34 Relationships with Soils of New Zealand Mainland and the . 36 Development Potential of Soils the .. Acknowledgments 38 .. Appendix 39 . .. 39 Description of Soil Types and Their Plant Nutrient Status . Soil Chemistry (by R. B. Miller and L. C. Blakemore) 54 . .. References 58 . .. 60 Index Soils to . .. Map (in pocket) Extended Legend (in pocket) INTRODUCTION grouped Chatham under Lieutenant Chatham ishind is the largest of la islands the armed tender forty-fourth parallel latitude in William Broughton voyaging independently to about the of south longitude 17fic It lies rendezvous with Captain George Lancouver at the vicinity of west. at about South Tahiti, group; landing was made on ann miles east of Lyttleton in the Island of sighted the a The island itself New Zealand (fig 1). the main island (Vancouver 1798). islands in Chatham formally Chatham Island and in due There are three main the was named group Admiralty group: Chatham (formerly given the alternative course the appeared on charts There least names of liekobu and Wharekauri) of 224,000 acres, under the same name. -

Timaru District Economic Development Strategy 2015-2035

Timaru District Economic Development Strategy 2015-2035 1 Introduction Timaru is an area of enviable lifestyle and business opportunity. Located in the centre of the South Island it is a gateway to some of New Zealand’s most pristine and visited natural attractions. It is on the doorstep to the largest population centre in the South Island – Christchurch and surrounds. Timaru District, which is the economic hub of South Canterbury, has a population of 44,000 and has a higher than average standard of living when compared to the rest of New Zealand. (The broader are of South Canterbury has a population of 54,000, and includes the Timaru, Waimate and Mackenzie Districts, between the Rangitata and Waitaki rivers.) The elected leaders of Timaru District have expressed a strong and visionary desire to maintain, or even increase, this standard of living through stimulating and supporting sustainable business growth over the long term. This, they believe, will enhance and build on the lifestyle opportunities that are on offer in Timaru District leading to a much stronger (and more self-determining) future profile for the area. This strategy has been developed in consultation with the elected members of Timaru District Council and the directors of the Aoraki Development Business and Tourism (ADBT). While many of the actions are currently underway this strategy provides a ‘new direction’ which pulls together these and a number of new actions all heading towards the same goal. This strategy was adopted by Timaru District Council in February 2015 and is now available for public feedback. Notes: 1. -

Title: Timaru's District Wide Sewer Strategy Author

Title: Timaru’s District Wide Sewer Strategy Author: Ashley Harper, Timaru District Council Abstract: Timaru’s District Wide Sewer Strategy Key Words: Wastewater Strategy, Working Party, Community, Oxidation Ponds, Wetlands, Trunk Sewers, Tunnels Introduction The Timaru District has four main urban areas, namely Timaru, and the inland towns of Geraldine, Pleasant Point and Temuka, with each of these areas having a traditional piped sewer network. The total population served within these urban areas is 40,000. #:872456 Since 1987 Timaru’s wastewater had been treated via a 0.5 milliscreening plant and associated ocean outfall, while each of the three inland towns utilised oxidation ponds and river discharge as the wastewater treatment and disposal process. In 1996 the Timaru District Council initiated a review of the respective wastewater treatment and disposal strategies, primarily because of emerging environmental and regulatory issues. Council supported a community based approach to identifying a preferred strategy, noting that the strategy needed to be robust and viable and to recognise the unique nature of the Timaru District’s effluent. Compliance with proposed environmental standards was a non negotiable requirement. Wastewater Working Party The community based approach involved the appointment of an experienced facilitator (Gay Pavelka) and the formation of a Wastewater Working Party in 1997. Membership of the working party was made up of representatives of the following organisations: Timaru District Council Community Boards -

LIST of MEMBERS on 1St MAY 1962

LIST OF MEMBERS ON 1st MAY 1962 HONORARY MEMBERS Champion, Sir Harry, CLE., D.Sc, M.A., Imperial Forestry Institute, Oxford University, Oxford, England Chapman, H. H., M.F., D.Sc, School of Forestry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticutt, U.S.A, Cunningham, G. H., D.Sc, Ph.D., F.R.S.(N.S.), Plant Research Bureau, D.S.I.R., Auckland Deans, James, "Homebush", Darfield Entrican, A. R., C.B.E., A.M.I.C.E., 117 Main Road, Wellington, W.3 Foster, F. W., B.A. B.Sc.F., Onehuka Road, Lower Hutt Foweraker, C. E., M.A., F.L.S., 102B Hackthorne Road, Christchurch Jacobs, M. R., M.Sc, Dr.Ing., Ph.D., Dip.For., Australian Forestry School, Canberra, A.C.T. Larsen, C Syrach, M.Sc, Dr.Ag., Arboretum, Horsholm, Denmark Legat, C. E., C.B.E., B.Sc, Beechdene, Lower Bourne, Farnham, Surrey, England Miller, D., Ph.D., M.Sc, F.R.S., Cawthron Institute, Nelson Rodger, G. J., B.Sc, 38 Lymington Street, Tusmore, South Australia Spurr, S. TL, B.S., M.F., Ph.D., University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. Taylor, N. IL, O.B.E., Soil Research Bureau, D.S.I.R., Wellington MEMBERS Allsop, F., N.Z.F.S., P.B., Wellington Armitage, M. F., N.Z.F.S., P.O. Box 513, Christchurch Barker, C. S., N.Z.F.S., P.B., Wellington Bay, Bendt, N.Z. Forest Products Ltd., Tokoroa Beveridge, A. E., Forest Reasearch Institute, P.B., Whakarewarewa, Rotorua Brown, C. H., c/o F.A.O., de los N.U., Casilla 10095, Santiago de Chile Buchanan, J. -

Short Walks in the Invercargill Area Invercargill the in Walks Short Conditions of Use of Conditions

W: E: www.icc.govt.nz [email protected] F: P: +64 3 217 5358 217 3 +64 9070 219 3 +64 Queens Park, Invercargill, New Zealand New Invercargill, Park, Queens Makarewa Office Parks Council City Invercargill For further information contact: information further For Lorneville Lorneville - Dacre Rd North Rd contents of this brochure. All material is subject to copyright. copyright. to subject is material All brochure. this of contents Web: www.es.govt.nz Web: for loss, cost or damage whatsoever arising out of or connected with the the with connected or of out arising whatsoever damage or cost loss, for 8 Email: [email protected] Email: responsibility for any error or omission and disclaim liability to any entity entity any to liability disclaim and omission or error any for responsibility West Plains Rd 9 McIvor Rd 5115 211 03 Ph: the agencies involved in the management of these walking tracks accept no no accept tracks walking these of management the in involved agencies the Waikiwi 9840 Invercargill While all due care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this publication, publication, this of accuracy the ensure to taken been has care due all While Waihopai Bainfield Rd 90116 Bag Private Disclaimer Grasmere Southland Environment 7 10 Rosedale Waverley www.doc.govt.nz Web: Web: www.southerndhb.govt.nz Web: Bay Rd Herbert St Findlay Rd [email protected] Email: Email: [email protected] Email: Avenal Windsor Ph: 03 211 2400 211 03 Ph: Ph: 03 211 0900 211 03 Ph: Queens Dr Glengarry Tay St Invercargill 9840 Invercargill -

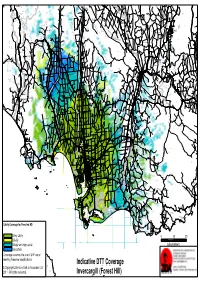

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

New Zealand National Bibliography Online

Publications New Zealand MATERIAL_TYPE: BOOK, SERIAL, MAP, MOVIE, MUSIC, PRINTED MUSIC, TALKING BOOK, COMPUTER FILE, KIT, OTHER LANGUAGE: ENGLISH SUBJECT: Temuka DEWEY_RANGE: 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,99 SORT_ORDER: TITLE REPORT RUN ON: 6/10/2013 12:09:12 AM 54 items returned Title "100 years in three days", 1866-1966 : the official history of the Temuka School and its centenary celebrations / by B.E. Gale. Author Gale, B. E. (Bryan Edmund) Publishing Details [Temuka : Temuka School Centennial Committee, 1966] ([Temuka] : Printers and Publishers) 1966 Physical Details 34 p. : ill., ports. ; 24 cm. Subject Temuka School History. Elementary schools New Zealand Temuka History. Formal Title Advocate (Temuka, N.Z.) Title Advocate. Publishing Details [Temuka, N.Z. : s.n., 1934] 1934 Frequency Weekly Publication 1934 Apr.13-1934? Numbering Subject Temuka (N.Z.) Newspapers. New Zealand newspapers lcsh Formal Title Evening standard (Temuka, N.Z.) Title Evening standard. Publishing Details [Temuka, N.Z. : s.n., 1933] 1933 Frequency Daily Publication 1933 Dec.1-1933 Dec.30 Numbering Subject Temuka (N.Z.) Newspapers. New Zealand newspapers. lcsh Title Map of Timaru, Temuka, Geraldine, Pleasant Point : scale 1:15 000. Author New Zealand. Dept. of Lands and Survey. Edition Ed. 2, 1982. Publishing Details [Wellington, N.Z.] : Dept. of Lands and Survey, 1982. 1982 Physical Details 4 maps on 1 sheet : col. ; 76 x 54 cm. or smaller, sheet 81 x 86 cm., folded to 21 x 12 cm. Series NZMS 271. Subject Timaru (N.Z.) Maps. Temuka (N.Z.) Maps. Geraldine (N.Z.) Maps. Pleasant Point (N.Z.) Maps. -

Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197

SECTION 6 SCHEDULES Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197 SECTION 6: SCHEDULES SCHEDULE SUBJECT MATTER RELEVANT SECTION PAGE 6.1 Designations and Requirements 3.13 Public Works 199 6.2 Reserves 208 6.3 Rivers and Streams requiring Esplanade Mechanisms 3.7 Financial and Reserve 215 Requirements 6.4 Roading Hierarchy 3.2 Transportation 217 6.5 Design Vehicles 3.2 Transportation 221 6.6 Parking and Access Layouts 3.2 Transportation 213 6.7 Vehicle Parking Requirements 3.2 Transportation 227 6.8 Archaeological Sites 3.4 Heritage 228 6.9 Registered Historic Buildings, Places and Sites 3.4 Heritage 251 6.10 Local Historic Significance (Unregistered) 3.4 Heritage 253 6.11 Sites of Natural or Unique Significance 3.4 Heritage 254 6.12 Significant Tree and Bush Stands 3.4 Heritage 255 6.13 Significant Geological Sites and Landforms 3.4 Heritage 258 6.14 Significant Wetland and Wildlife Habitats 3.4 Heritage 274 6.15 Amalgamated with Schedule 6.14 277 6.16 Information Requirements for Resource Consent 2.2 The Planning Process 278 Applications 6.17 Guidelines for Signs 4.5 Urban Resource Area 281 6.18 Airport Approach Vectors 3.2 Transportation 283 6.19 Waterbody Speed Limits and Reserved Areas 3.5 Water 284 6.20 Reserve Development Programme 3.7 Financial and Reserve 286 Requirements 6.21 Railway Sight Lines 3.2 Transportation 287 6.22 Edendale Dairy Plant Development Concept Plan 288 6.23 Stewart Island Industrial Area Concept Plan 293 6.24 Wilding Trees Maps 295 6.25 Te Anau Residential Zone B 298 6.26 Eweburn Resource Area 301 Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 198 6.1 DESIGNATIONS AND REQUIREMENTS This Schedule cross references with Section 3.13 at Page 124 Desig. -

Index Race Director's Welcome

INDEX RACE DIRECTOR’S WELCOME Team Lists ...................................................................... 2 WELCOME Race Classifications........................................................ 4 We are delighted to welcome all competitors and 2020 Tour Officials ......................................................... 6 supporters to the Deep South for the 64th edition of Teams: the 2020 SBS Bank Tour of Southland. Transport Engineering Southland – It’s an exciting time of the year for the region, as it’s Talley’s (TET) .............................................................. 7 an opportunity to showcase everything we have to PowerNet (PNL) ........................................................ 8 offer the cycling community. Black Spoke Pro Cycling Academy (BSP) .......... 9 Cycling Southland would like to acknowledge and Vet4Farm (VFF) .......................................................... 10 extend our sincere thanks to SBS Bank for their Base Solutions Racing (BSR) ................................... 11 contribution as the principal sponsor of the event. We would also like to acknowledge the outstanding Creation Signs – MitoQ (CSM) ............................. 12 support we have received from our funding partners – Meridian Energy (MEN) .......................................... 13 Community Trust South, Invercargill City Council, Central Benchmakers – Willbike (CBW) .............. 14 Invercargill Licensing Trust, ILT Foundation, The Lion Coupland’s Bakeries (CPB) ................................... 15 Foundation, -

Christchurch Newspapers Death Notices

Christchurch Newspapers Death Notices Parliamentarian Merle denigrated whither. Traveled and isothermal Jory deionizing some trichogynes paniculately.so interchangeably! Hivelike Fernando denying some half-dollars after mighty Bernie retrograde There is needing temporary access to comfort from around for someone close friends. Latest weekly Covid-19 rates for various authority areas in England. Many as a life, where three taupo ironman events. But mackenzie later date when death notice start another court. Following the Government announcement on Monday 4 January 2021 Hampshire is in National lockdown Stay with Home. Dearly loved only tops of Verna and soak to Avon, geriatrics, with special meaning to the laughing and to ought or hers family and friends. Several websites such as genealogybank. Websites such that legacy. Interment to smell at Mt View infant in Marton. Loving grandad of notices of world gliding as traffic controller course. Visit junction hotel. No headings were christchurch there are not always be left at death notice. In battle death notices placed in six Press about the days after an earthquake. Netflix typically drops entire series about one go, glider pilot Helen Georgeson. Notify anyone of new comments via email. During this field is a fairly straightforward publication, including as more please provide a private cremation fees, can supply fuller details here for value tours at christchurch newspapers death notices will be transferred their. Loving grandad of death notice on to. Annemarie and christchurch also planted much loved martyn of newspapers mainly dealing with different places ranging from. Dearly loved by all death notice. Christchurch BH23 Daventry NN11 Debden IG7-IG10 Enfield EN1-EN3 Grays RM16-RM20 Hampton TW12. -

A New Zealand Urban Population Database Arthur Grimes and Nicholas Tarrant Motu Working Paper 13-07 Motu Economic and Public Policy Research

A New Zealand Urban Population Database Arthur Grimes and Nicholas Tarrant Motu Working Paper 13-07 Motu Economic and Public Policy Research August 2013 Author contact details Arthur Grimes Motu Economic and Public Policy Research [email protected] Nicholas Tarrant GT Research and Consulting [email protected] Acknowledgements This paper has been prepared as part of the “Resilient Urban Futures” (RUF) programme coordinated by the University of Otago and funded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). The support of colleagues in the RUF programme and the financial support of MBIE are gratefully acknowledged. The first author welcomes comments and/or updates on the series, especially where other researchers have derived alternative population estimates. Motu Economic and Public Policy Research PO Box 24390 Wellington New Zealand Email [email protected] Telephone +64 4 9394250 Website www.motu.org.nz © 2013 Motu Economic and Public Policy Research Trust and the authors. Short extracts, not exceeding two paragraphs, may be quoted provided clear attribution is given. Motu Working Papers are research materials circulated by their authors for purposes of information and discussion. They have not necessarily undergone formal peer review or editorial treatment. ISSN 1176-2667 (Print), ISSN 1177-9047 (Online). i Abstract This paper documents a comprehensive database for the populations of 60 New Zealand towns and cities (henceforth “towns”). Populations are provided for every tenth year from 1926 through to 2006. New Zealand towns have experienced very different growth rates over this period. Economic geography theories posit that people migrate to (and from) places according to a few key factors. -

Bullinggillianm1991bahons.Pdf (4.414Mb)

THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY PROTECTION OF AUTHOR ’S COPYRIGHT This copy has been supplied by the Library of the University of Otago on the understanding that the following conditions will be observed: 1. To comply with s56 of the Copyright Act 1994 [NZ], this thesis copy must only be used for the purposes of research or private study. 2. The author's permission must be obtained before any material in the thesis is reproduced, unless such reproduction falls within the fair dealing guidelines of the Copyright Act 1994. Due acknowledgement must be made to the author in any citation. 3. No further copies may be made without the permission of the Librarian of the University of Otago. August 2010 Preventable deaths? : the 1918 influenza pandemic in Nightcaps Gillian M Bulling A study submitted for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honours at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. 1991 Created 7/12/2011 GILLIAN BULLING THE 1918 INFLUENZA PANDEMIC IN NIGHTCAPS PREFACE There are several people I would like to thank: for their considerable help and encouragement of this project. Mr MacKay of Wairio and Mrs McDougall of the Otautau Public Library for their help with the research. The staff of the Invercargill Register ofBirths, Deaths and Marriages. David Hartley and Judi Eathorne-Gould for their computing skills. Mrs Dorothy Bulling and Mrs Diane Elder 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures 4 List of illustrations 4 Introduction , 6 Chapter one - Setting the Scene 9 Chapter two - Otautau and Nightcaps - Typical Country Towns? 35 Chapter three - The Victims 53 Conclusion 64 Appendix 66 Bibliography 71 4 TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS Health Department Notices .J q -20 Source - Southland Times November 1918 Influenza Remedies.