Liquidity Provision During the Crisis of 1914: Private and Public Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record-Senate. 3419

1908. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 3419 Also, petition of Radiant Lodge, No. 416, Brotherhood of Lo MESSAGE FROM THE HOUSE. comoti •e Firemen and Enginemen, of Mahoning, Pa., in favor A message from the House of Representatives, by 1\Ir. W. J. of S. 4.260--to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Com BROWNING, its Chief Clerk, announced that the House had merce. passed the following bill and joint resolution : Also, petition of Blue Mountain Lodge, No. 694, Brotherhood S. 626 . .An act. authorizing and empowering the Secretary of of Railway Trainmen, of Marysville, Pa., in favor of S. 4260- War to locate a right of way for, and granting the same, and to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. a right to operate and maintain a line of railroad through the Also, petition of Chemung .Lodge, No. 229, Brotherhood of Three Tree Point .Military Reservation, in the State of Wash Railway Trainmen, of Blossburg, Pa., for S. 4260--to the Com ington, to the Grays Harbor and Columbia River Railway Com mittee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. pany, its successors and assigns; and Also, petition of Chamber of Commerce of Pittsburg, Pa., to S. R. 69. Joint resolution granting authority for the use of require common carriers of interstate and foreign commerce to certain balances of appropriations for the Light-House Estab make full reports of all accidents to the Interstate Commer~e lishment, to be available for certain named purposes. Commission and authorizing investigation thereof by sa1d The message also announced that the House had passed Commission:_to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Com the following bil1s with amendments, in which it requested the merce. -

Who Controls the Gold Stealing New York Fed Bank? Presented January 2014 by Charles Savoie “WE HAVE the QUESTION of GOLD UNDER CONSTANT SURVEILLANCE

Who Controls The Gold Stealing New York Fed Bank? Presented January 2014 by Charles Savoie “WE HAVE THE QUESTION OF GOLD UNDER CONSTANT SURVEILLANCE. WE HAVE BEEN UNDER ATTACK BECAUSE OF OUR ATTITUDE TOWARDS GOLD. A FREE GOLD MARKET IS HERESY. THERE IS NO SENSE IN A MAKE BELIEVE FREE GOLD MARKET. GOLD HAS NO USEFUL PURPOSE TO SERVE IN THE POCKETS OF THE PEOPLE. THERE IS NO HIDDEN AGENDA.” ---Pilgrims Society member Allan Sproul, president of Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1941-1956. “ANY ATTEMPT TO WRITE UP THE PRICE OF GOLD WOULD ASSUREDLY BE MATCHED, WITHIN HOURS, BY COMPARABLE AND OFFSETTING ACTION.” ---Robert V. Roosa, Pilgrims Society, in “Monetary Reform for the World Economy” (1965). Roosa was with the New York Federal Reserve Bank, 1946-1960 when he moved to Treasury to fight silver coinage! “The most powerful international society on earth, the “Pilgrims,” is so wrapped in silence that few Americans know even of its existence since 1903.” ---E.C. Knuth, “The Empire of The City: World Superstate” (Milwaukee, 1946), page 9. “A cold blooded attitude is a necessary part of my Midas touch!” ---financier Scott Breckenridge in “The Midas Man,” April 13, 1966 “The Big Valley” The Pilgrims Society is the last great secret of modern history! ******************** Before gold goes berserk like Godzilla rampaging across Tokyo--- and frees silver to supernova---let’s have a look into backgrounds of key Federal Reserve personalities, with special focus on the New York Federal Reserve Bank. The NYFED is the center of an international scandal regarding refusal (incapacity) to return German-owned gold. -

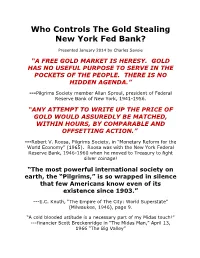

Who Controls the Gold Stealing New York Fed Bank?

Who Controls The Gold Stealing New York Fed Bank? Presented January 2014 by Charles Savoie “A FREE GOLD MARKET IS HERESY. GOLD HAS NO USEFUL PURPOSE TO SERVE IN THE POCKETS OF THE PEOPLE. THERE IS NO HIDDEN AGENDA.” ---Pilgrims Society member Allan Sproul, president of Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1941-1956. “ANY ATTEMPT TO WRITE UP THE PRICE OF GOLD WOULD ASSUREDLY BE MATCHED, WITHIN HOURS, BY COMPARABLE AND OFFSETTING ACTION.” ---Robert V. Roosa, Pilgrims Society, in “Monetary Reform for the World Economy” (1965). Roosa was with the New York Federal Reserve Bank, 1946-1960 when he moved to Treasury to fight silver coinage! “The most powerful international society on earth, the “Pilgrims,” is so wrapped in silence that few Americans know even of its existence since 1903.” ---E.C. Knuth, “The Empire of The City: World Superstate” (Milwaukee, 1946), page 9. “A cold blooded attitude is a necessary part of my Midas touch!” ---financier Scott Breckenridge in “The Midas Man,” April 13, 1966 “The Big Valley” The Pilgrims Society is the last great secret of modern history! ******************** Before gold goes berserk like Godzilla rampaging across Tokyo--- and frees silver to supernova---let’s have a look into backgrounds of key Federal Reserve personalities, with special focus on the New York Federal Reserve Bank. The NYFED is the center of an international scandal regarding refusal (incapacity) to return German-owned gold. The outrage will worsen. I hope to add to examining this Pandora’s Box of gold suppression by documenting membership of key Fed officials in The Pilgrims Society, which has existed unknown to the public for over a century, and which shoved the world financial system off gold and silver through a series of breathtakingly villainous schemes as profusely documented in http://silverstealers.net/tss.html Just like President Nixon, who stole gold from foreign dollar holders by closing the Treasury gold window, the NYFED is a Pilgrims Society entity. -

Brief Biographies of American Architects Who Died Between 1897 and 1947

Brief Biographies of American Architects Who Died Between 1897 and 1947 Transcribed from the American Art Annual by Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Director, Maine Historic Preservation Commission. Between 1897 and 1947 the American Art Annual and its successor volume Who's Who in American Art included brief obituaries of prominent American artists, sculptors, and architects. During this fifty-year period, the lives of more than twelve-hundred architects were summarized in anywhere from a few lines to several paragraphs. Recognizing the reference value of this information, I have carefully made verbatim transcriptions of these biographical notices, substituting full wording for abbreviations to provide for easier reading. After each entry, I have cited the volume in which the notice appeared and its date. The word "photo" after an architect's name indicates that a picture and copy negative of that individual is on file at the Maine Historic Preservation Commission. While the Art Annual and Who's Who contain few photographs of the architects, the Commission has gathered these from many sources and is pleased to make them available to researchers. The full text of these biographies are ordered alphabetically by surname: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W Y Z For further information, please contact: Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Director Maine Historic Preservation Commission 55 Capitol Street, 65 State House Station Augusta, Maine 04333-0065 Telephone: 207/287-2132 FAX: 207/287-2335 E-Mail: [email protected] AMERICAN ARCHITECTS' BIOGRAPHIES: ABELL, W. -

FINANCIAL HISTORY of the UNITED STATES a FINANCIAL HISTORY of the UNITED STATES

A FINANCIAL HISTORY of the UNITED STATES A FINANCIAL HISTORY of the UNITED STATES Volume II From J.P. Morgan to the Institutional Investor (1900 -1970) Jerry W. Markham M.E.Sharpe Armonk, New York London, England Copyright © 2002 by M. E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 80 Business Park Drive, Armonk, New York 10504. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Markham, Jerry W. A financial history of the United States / Jerry W. Markham. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: v. 1. From Christopher Columbus to the Robber Barons (1492–1900) — v. 2. From J.P. Morgan to the institutional investor (1900–1970) — v. 3. From the age of derivatives into the new millennium (1970–2001) ISBN 0-7656-0730-1 (alk. paper) 1. Finance—United States—History. I. Title. HG181.M297 2001 332’.0973—dc21 00-054917 Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.48-1984. ~ BM (c)10987654321 For my parents, John and Marie Markham In every generation concern has arisen, sometimes to the boiling point. Fear has emerged that the United States might one day discover that a relatively small group of individuals, especially through banking institutions they headed, might become virtual masters of the economic destiny of the United States. —Adolf A. Berle, February 1969 Contents List of Illustrations xiii Preface xv Acknowledgments xvii Introduction xix Chapter 1. -

The City Record. Vol

THE CITY RECORD. VOL. XXXVI. NEW YORK, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 1908. NUMBER 107795. 2:30 p. m.—Commissioner Bassett's Room.—Order No. 430.—LONG THE CITY RECORD. ISLAND R. R. Co.—"Opening of Chester Street, between Riverdale Avenue and East 98th Street."—Commissioner Bassett. OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK. 2 :30 p. in.—Order No. 800.—I' ULTON Sr. R. R. Co., and Gilbert H. Published Under Authority of Section 1526, Greater New York Charter, by the Montague, Receiver.—Mallory Steamship Co., ct al., Complainants.— BOARD OF CITY RECORD. "Restoration of Cars on Fulton Street Line."—Commissioner Maltbie. GEORGE B. McCLELLAN, MAYOL 2:30 p. m.—Commissioner McCarroll's Room.—Order No. 787.—LONG Covasal. HERMAN A. METZ, COMPTROLLER. FRANCIS K. PENDLETON. CoaroRATION ISLAND R. R. Co.—"To fix routes for connections and extensions, etc., on streets including Atlantic Avenue."—Commissioner McCarroll. PATRICK J. TRACY, SUPEavISOS. 3 p. m.—Room 31o.—Order No. 788.—FREDERICK W. WHITRIDGE, RECEIVER, Published daily, at 9 a. m., except legal holidays. UNION Ry. Co., AND J. ADDISON YOUNG. RECEIVER, WESTCIIESTER Subscription. $9.3o per year, exclusive of supplements. Three cents a copy. ELECTRIC R. R. Co.—"Discontinuance of Transfers."—Commissioner Eustis. SUPPLEMENTS: Civil List (containing names, salaries, etc., of the city employees), 25 cents; Official Canvass of Votes, ro cents; Registry and Enrollment Lists, 5 cents each assembly district; Friday, November 6.—Chairman's Room.—Order No. I2L—I NTERDOROUGH RAPID Law Department and Finance Department supplements, io cents each; Annual Assessed Valuation ot TRANSIT Co.—"P,lock Signal System —Local Subway Tracks."— Real Estate, 25 cents each section. -

In the United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District of Texas Houston Division

Case 20-33113 Document 61 Filed in TXSB on 07/31/20 Page 1 of 21 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION ) In re: ) Chapter 15 ) TECHNICOLOR S.A., 1 ) Case No. 20-33113 (DRJ) ) Debtor in a Foreign Proceeding. ) ) CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Nathaniel R. Repko, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtor in the above-captioned case. On July 29, 2020 at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following document to be served (i) via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, (ii) via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B, (iii) via overnight mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit C, and (iv) via first-class mail on six (6) confidential parties not included herein: • Foreign Representative’s Witness and Exhibit List for July 31, 2020 Hearing (Docket No. 53) Dated: July 31, 2020 /s/ Nathaniel R. Repko Nathaniel R. Repko STRETTO 7 Times Square, 16th Floor New York, NY 10036 [email protected] ________________________________________ 1 The location of debtor Technicolor S.A.’s principal place of business and its service address in this chapter 15 case is 8-10 rue du Renard, 75004 Paris, France. Case 20-33113 Document 61 Filed in TXSB on 07/31/20 Page 2 of 21 Exhibit A Case 20-33113 Document 61 Filed in TXSB on 07/31/20 Page 3 of 21 Exhibit A Served Via First-Class Mail Name Attention Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 City State Zip Country ACCUNIA EUROPEAN CLO I B.V., ACCUNIA EUROPEAN CLO II B.V. -

The Life Story of J. Pierpont Morgan : a Biography

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Library Cornell University CT275.M84 H84 Life story of J:..P!SfBSBLM8W«iiiiAl'''° 3 1924 032 366 332 Cornell University Library The original of tliis bool< is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924032366332 THE LIFE STORY OF J. PIERPONT MORGAN J. PIERPONT MORGAN THE LIFE STORY OF PIERPONT MORGAN A BIOGRAPHY BY CARL HOVEY ILLUSTRATED flew !9cr?s STURGIS & WALTON COMPANY 5 7i' / 'PC/ Copyright lOII By STURGIS & WALTON COMPANY Set np and electrotyped. Publiihed October, Mil Reprinted May, 1912 PEEFACE The biograpliy of a living man is a special sort of thing to write or to read, and requires a little explanation from the author. Un- doubtedly the reader needs to know whether the thread of argument, which forms the more or less unconscious basis of every work of biographical writing, came, in this in- stance, from the subject himself duly posing for the public and expounding his character according to his own notions, or whether it proceeded independently from the writer's mind. The fact that this life takes Mr. Morgan neither angrily nor bitterly, nor extrav- agantly nor pathetically, nor according to any of the obvious methods of the Simday special articles (in which, up to now, his life has been exclusively set forth) but under- takes to describe him seriously and intelli- gently, vnll undoubtedly convince some sim- ple souls that this tone was in some sense inspired. -

Silver Squelchers #1 & Their Interesting Associates

SILVER SQUELCHERS #1 & THEIR INTERESTING ASSOCIATES Presented August 2014 by Charles Savoie www.nosilvernationalization.org “It is a burning shame in the eyes of all the world that the United States, the greatest producer of silver, will not protect her own precious metal product. It is a case without a parallel in the history of nations down through all the ages.” ---Elihu Jerome Farmer, publisher of “The Silver Dollar,” Cleveland, August 1, 1887, page 2 (page 1 mentioned “the anti-silver conspiracy in the Western hemisphere.”) Referring to The Pilgrims Society, which I’ve been after since December 2004, Before It’s News, sourcing info from my talented European colleague, Joel Van Der Reijden, reckons it this way (I concur) --- “This is the most powerful and secretive group in the world bar none. “ Source--- http://beforeitsnews.com/power-elite/2014/04/the-secret-club- called-the-pilgrim-society During 1902 and 1903 an organization was founded which I came to regard as history’s most interesting organization. This is The Pilgrims Society of London and New York, as those who have followed my presentations are aware. This marks the start of a series of eleven presentations. We will examine 15 names derived from lists of this organization from the following years---1902- 1903; 1914; 1924; 1933; 1940; 1949; 1957; 1969; 1974; 1980; and the final installment, to be derived from names found by other means than rosters---because to date, there ARE no rosters for this group available since 1980! These rosters, except the first one, all came from lists which “leaked” out into possession of nonmembers. -

3 Silver Squelchers & Their Interesting Associates

#3 SILVER SQUELCHERS & THEIR INTERESTING ASSOCIATES Presented October 2014 by Charles Savoie www.nosilvernationalization.org President Lincoln was aware of monopolistic banking amalgamations and remarked--- “They have him in his prison house. They have searched his person and have left no prying instrument with him. One after another, they have closed the heavy iron doors upon him and now they have him, as it were, bolted in with a lock of one hundred keys which can never be unlocked without the concurrence of every key; the keys in the hands of a hundred different men, and they scattered to a hundred different places; and they stand musing as to what invention in all the dominion of mind and matter can be produced to make the impossibility of his escape more complete than it is.” In this episode we’ll have a look at another group of 15 members of The Pilgrims Society from the 1924 roster as we progress across this groups concealed history towards the present. Naturally these same 15 men also appeared in rosters before and afterwards, but they’ll serve as a representation of the 1924 list. These are the worthy gentlemen who have been opposing free markets and using government power to bankrupt their competitors. As you read this series on the Silver Squelchers, bear in mind this organization is still on the scene, and remains the last major globalist group in the world still refusing to post rosters visibly in the public domain. Why do they refuse release of rosters? The most defensible postulate is- --they are the management of the other globalist groups---this single organization is the wellspring of the problems of warfare, monetary subversion, export of manufacturing jobs, pharmaceutical attacks on the public, genetically modified foods, loss of privacy and civil liberties, loss of parental control over children, refusal to seal the Southern border with Mexico, and much more. -

The War Plotters of Wall Street

HG WAR TIERS of \sfoMtreet CHARLES' A. COLL.AVAN: Price 25 Cents THE WAR PLOTTERS OF WALL STREET BY CHARLES A. COLLMAN THE FATHERLAND CORPORATION NEW YORK 1915 v Copyright, 1915, by THE FATHERLAND CORPORATION COXTEXTS CHAPTER PAGE I. YOUNG MORGAN, BRITAIN'S MUNITIONS AGENT 7 II. THE WAR STOCK GAMBLERS 16 III. THE CURTAIN RAISED ON WALL STREET'S UNDERWORLD . 26 IV. WALL STREET'S BRITISH GOLD PLOT 37 V. OUR BANKRUPT "LADY OF THE SNOWS" 48 VI. THE CRIME OF THE YEAR 1915 59 VII. THE SHAM PEACE SOCIETIES 68 VIII. RED LIGHTS AHEAD! 78 IX. THE "AMERICAN" PILGRIMS 88 X. THE MEN WHO TOASTED THE CZAR 98 XI. WHO is USING OUR LIFE INSURANCE FUNDS? 105 XII. Is WALL STREET USING SAVINGS BANK DEPOSITS IN SECRET LOANS TO RUSSIA, FRANCE AND ENGLAND? .... 119 XIII. THE GREAT NEWS CONSPIRACY How UNSCRUPULOUS NEWS- PAPER OWNERS, AT THE BEHEST OF WALL STREET, DE- LIBERATELY DECEIVED THE AMERICAN PEOPLE . 131 333432 PREFACE These stories were written under fire, at a time when treason stalked through the land. They are human records of the amaz- ing acts of men who schemed and strove and plotted to blind ninety million people. Then these men, with immense cunning, set themselves to work at a game that is old as history. They coined great fortunes for themselves from the mad passions and blind hatreds they had instilled into their fellow-men. We, who tried to expose these conspirators, were villified, threatened, hounded by the most powerful and unscrupulous band that ever organized itself to ruin a country and its people in the interest of a foreign race. -

Financial History of the United States / Jerry W

! &).!.#)!, ()34/29 OF THE 5.)4%$ 34!4%3 ! &).!.#)!, ()34/29 OF THE 5.)4%$ 34!4%3 6OLUME )) &ROM *0 -ORGAN TO THE )NSTITUTIONAL )NVESTOR *ERRY 7 -ARKHAM %3HARPE !RMONK .EW 9ORK ,ONDON %NGLAND Copyright © 2002 by M. E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 80 Business Park Drive, Armonk, New York 10504. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Markham, Jerry W. A financial history of the United States / Jerry W. Markham. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: v. 1. From Christopher Columbus to the Robber Barons (1492–1900) — v. 2. From J.P. Morgan to the institutional investor (1900–1970) — v. 3. From the age of derivatives into the new millennium (1970–2001) ISBN 0-7656-0730-1 (alk. paper) 1. Finance—United States—History. I. Title. HG181.M297 2001 332’.0973—dc21 00-054917 Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.48-1984. ~ BM (c) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For my parents, John and Marie Markham In every generation concern has arisen, sometimes to the boiling point. Fear has emerged that the United States might one day discover that a relatively small group of individuals, especially through banking institutions they headed, might become virtual masters of the economic destiny of the United States.