Density and Intervention.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early 'Urban America'

CCAPA AICP Exam Presentation Planning History, Theory, and Other Stuff Donald J. Poland, PhD, AICP Senior VP & Managing Director, Urban Planning Goman+York Property Advisors, LLC www.gomanyork.com East Hartford, CT 06108 860-655-6897 [email protected] A Few Words of Advice • Repetitive study over key items is best. • Test yourself. • Know when to stop. • Learn how to think like the test writers (and APA). • Know the code of ethics. • Scout out the test location before hand. What is Planning? A Painless Intro to Planning Theory • Rational Method = comprehensive planning – Myerson and Banfield • Incremental (muddling through) = win little battles that hopefully add up to something – Charles Lindblom • Transactive = social development/constituency building • Advocacy = applying social justice – Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Public Participation – Paul Davidoff – advocacy planning American Planning before 1800 • European Traditions – New England, New Amsterdam, & the village tradition – Tidewater and the ‘Town Acts’ – The Carolinas/Georgia and the Renaissance Style – L’Enfant, Washington D.C., & Baroque Style (1791) • Planning was Architectural • Planning was plotting street layouts • There wasn’t much of it… The 1800’s and Planning Issues • The ‘frontier’ is more distant & less appealing • Massive immigration • Industrialization & Urbanization • Problems of the Industrial City – Poverty, pollution, overcrowding, disease, unrest • Planning comes to the rescue – NYC as epicenter – Central Park 1853 – 1857 (Olmsted & Vaux) – Tenement Laws Planning Prior to WWI • Public Awareness of the Problems – Jacob Riis • ‘How the Other Half Lives’ (1890) • Exposed the deplorable conditions of tenement house life in New York City – Upton Sinclair • ‘The Jungle’ (1905) – William Booth • The Salvation Army (1891) • Solutions – Zoning and the Public Health Movement – New Towns, Garden Cities, and Streetcar Suburbs – The City Beautiful and City Planning Public Health Movement • Cities as unhealthy places – ‘The Great Stink’, Cholera, Tuberculosis, Alcoholism…. -

Resourceful Disciple

RESOURCEFUL DISCIPLE the LIFE, TIMES, & EXTENDED FAMILY of THOMAS EDWARDS BASSETT (1862-1926) by Arthur R. Bassett Prologue Purposed Audience and Prepared Authorship Part 1: For Whom the Bells Toll: Three Target Audiences It might be argued that every written composition, either by intent or subconsciously, has an intended audience to whom it is addressed; this biography, as indicated in the title, has three: 1) those interested in the facts surrounding the life of Thomas E. Bassett, 2) those interested in his times, and 3) those with an interest in his extended family. 1) Those Interested in His Life In one sense, this is the story of a single solitary life, selected and plucked from a pool of billions. It is the life of Thomas E. Bassett. He is not only my grandfather; he is also one of my heroes, so I hope that I can be forgiven if at times this biography exhibits overtones of a hagiography.1 I feel that his story deserves to be preserved, if for no other reason than his life was so extraordinary. It is truly a classic example of the America dream come true. Like most of his immediate descendants, I had heard the litany of his achievements from my very early childhood: first state senator from his county, first schoolteacher in Rexburg, first postmaster, newspaper editor, stake president, etc. However, as far as I know, no one has laid out the entire tapestry of his life in such a way that the chronological order and interrelationship of these accomplishments is demonstrated. This has been a major part of my project in this biography. -

Modernism in Bartholomew County, Indiana, from 1942

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MODERNISM IN BARTHOLOMEW COUNTY, INDIANA, FROM 1942 Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form E. STATEMENT OF HISTORIC CONTEXTS INTRODUCTION This National Historic Landmark Theme Study, entitled “Modernism in Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Design and Art in Bartholomew County, Indiana from 1942,” is a revision of an earlier study, “Modernism in Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Design and Art in Bartholomew County, Indiana, 1942-1999.” The initial documentation was completed in 1999 and endorsed by the Landmarks Committee at its April 2000 meeting. It led to the designation of six Bartholomew County buildings as National Historic Landmarks in 2000 and 2001 First Christian Church (Eliel Saarinen, 1942; NHL, 2001), the Irwin Union Bank and Trust (Eero Saarinen, 1954; NHL, 2000), the Miller House (Eero Saarinen, 1955; NHL, 2000), the Mabel McDowell School (John Carl Warnecke, 1960; NHL, 2001), North Christian Church (Eero Saarinen, 1964; NHL, 2000) and First Baptist Church (Harry Weese, 1965; NHL, 2000). No fewer than ninety-five other built works of architecture or landscape architecture by major American architects in Columbus and greater Bartholomew County were included in the study, plus many renovations and an extensive number of unbuilt projects. In 2007, a request to lengthen the period of significance for the theme study as it specifically relates to the registration requirements for properties, from 1965 to 1973, was accepted by the NHL program and the original study was revised to define a more natural cut-off date with regard to both Modern design trends and the pace of Bartholomew County’s cycles of new construction. -

Bassett Family Newsletter, Volume XIV, Issue 6, 19 Jun 2016 (1

Bassett Family Newsletter, Volume XIV, Issue 6, 19 Jun 2016 (1) Welcome (2) Abbot Bassett scrapbook pictures (2 of 3) (3) Frederick William Bassett and his wife’s school chum (4) Margaret (Bassett) Johnson, actress, singer and model (5) Four generation picture of Eliza Bassett Warner and family (6) Family photo of Albert Moses Bassett of Lawrence, Massachusetts (7) Autobiography of Edward Murray Bassett (8) New family lines combined or added since the last newsletter (9) DNA project update Section 1 - Welcome With the beginning of warm weather, I continue to struggle getting my research done in a timely manner and getting each month’s newsletter ready for publication. Totals number of individuals loaded into the Bassett website: 140.470 Section 2 - Featured Bassett: Abbot Bassett Family Scrapbook pictures (2 of 3) Abbot Bassett descends from #4B William Bassett of Lynn, Massachusetts as follows: William Bassett (b. 1624) and wife Sarah Burt William Bassett (b. 1647) and wife Sarah Hood John Bassett (b.1682) and wife Abigail Berry Zephaniah Bassett and wife Mary Edward Bassett (b. 1742) and wife Huldah Cleverly Samuel Bassett (b. 1775) and wife Elizabeth Scott Edward Bassett (b. 1809) and wife Clara Jane Morgan Abbot Bassett (b. 1845 Chelsea) Edward Bassett, father of Abbot Bassett Abbot was at one time the president of the Bassett Family Association (1899) and served as secretary of the League of American Wheelman. Birthday Card Invitation, November 1, 1882 Abbot Bassett and wife Helen, 1873 (They were married in 1873) * * * * * Section 3 - Featured Bassett: Frederick William Bassett and his wife’s School Chum Frederick William Bassett descends from #180 William Bassett of Hadlow, Kent as follows: William Bassett William Bassett (b. -

Congressional Record-Senate. 3419

1908. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 3419 Also, petition of Radiant Lodge, No. 416, Brotherhood of Lo MESSAGE FROM THE HOUSE. comoti •e Firemen and Enginemen, of Mahoning, Pa., in favor A message from the House of Representatives, by 1\Ir. W. J. of S. 4.260--to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Com BROWNING, its Chief Clerk, announced that the House had merce. passed the following bill and joint resolution : Also, petition of Blue Mountain Lodge, No. 694, Brotherhood S. 626 . .An act. authorizing and empowering the Secretary of of Railway Trainmen, of Marysville, Pa., in favor of S. 4260- War to locate a right of way for, and granting the same, and to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. a right to operate and maintain a line of railroad through the Also, petition of Chemung .Lodge, No. 229, Brotherhood of Three Tree Point .Military Reservation, in the State of Wash Railway Trainmen, of Blossburg, Pa., for S. 4260--to the Com ington, to the Grays Harbor and Columbia River Railway Com mittee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. pany, its successors and assigns; and Also, petition of Chamber of Commerce of Pittsburg, Pa., to S. R. 69. Joint resolution granting authority for the use of require common carriers of interstate and foreign commerce to certain balances of appropriations for the Light-House Estab make full reports of all accidents to the Interstate Commer~e lishment, to be available for certain named purposes. Commission and authorizing investigation thereof by sa1d The message also announced that the House had passed Commission:_to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Com the following bil1s with amendments, in which it requested the merce. -

“The 1961 New York City Zoning Resolution, Privately Owned Public

“The 1961 New York City Zoning Resolution, Privately Owned Public Space and the Question of Spatial Quality - The Pedestrian Through-Block Connections Forming the Sixth-and-a-Half Avenue as Examples of the Concept” University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts Department of Philosophy, History, Culture and Art Studies Art History Master’s thesis Essi Rautiola April 2016 Tiedekunta/Osasto Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos/Institution– Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Filosofian, historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Tekijä/Författare – Author Essi Rautiola Työn nimi / Arbetets titel – Title The 1961 New York City Zoning Resolution, Privately Owned Public Space and the Question of Spatial Quality - The Pedestrian Through-Block Connections Forming the Sixth-and-a-Half Avenue as Examples of the Concept Oppiaine /Läroämne – Subject Taidehistoria Työn laji/Arbetets art – Level Aika/Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä/ Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu Huhtikuu 2016 104 + 9 Tiivistelmä/Referat – Abstract Tutkielma käsittelee New Yorkin kaupungin kaavoituslainsäädännön kerrosneliöbonusjärjestelmää sekä sen synnyttämiä yksityisomisteisia julkisia tiloja ja niiden tilallista laatua nykyisten ihanteiden valossa. Esimerkkitiloina käytetään Manhattanin keskikaupungille kuuden korttelin alueelle sijoittuvaa kymmenen sisä- ja ulkotilan sarjaa. Kerrosneliöbonusjärjestelmä on ollut osa kaupungin kaavoituslainsäädäntöä vuodesta 1961 alkaen ja liittyy olennaisesti New Yorkin kaupungin korkean rakentamisen perinteisiin. Se on mahdollistanut ylimääräisten -

Introduction to Zoning

4 Introduction to Zoning Zoning establishes an orderly pattern of development limits on the use of land, rather than a set of a rmative across neighborhoods, and the city as a whole, by requirements for a property owner to use a property in a identifying what is permissible on a piece of property. It particular way. is a law which organizes how land may be used, enacted pursuant to State authorizing legislation and, in New York New York City zoning regulations originally stated which City, the City Charter. Zoning is not planning itself, but is uses could be conducted on a given piece of property, and oen one of its results; it is a tool that oen accompanies, placed limits on how a building could be shaped, or its and eectively implements, a well-considered plan. bulk. Today, zoning continues to regulate land use under Zoning regulations in New York City are contained within a more expansive concept of use and bulk provisions to the Zoning Resolution. encompass issues such as o-street parking, aordable housing, walkability, public space, sustainability and Under New York Citys Zoning Resolution, land climate change resiliency. throughout the City is divided into districts, or zones, where similar rules are in eect. Zoning regulations New York Citys Zoning Resolution became eective in are assigned based on consideration of relevant land 1961, replacing an earlier Resolution dating from 1916. It use issues, rather than other factors such as property has been amended many times since 1961, reecting the ownership or nancial considerations. By virtue of changing needs and priorities of the city. -

People in Planning

People in Planning Saul Alinsky—advocacy planning; vision of planning centered on community organizing; Back of the Yards movement; Rules for Radicals (1971). William Alonso—land rent curve; bid-rent theory (1960): cost of land, intensity of development, and concentration of population decline as you move away from CBD. Sherry Arnstein—wrote Ladder of Participation (1969), which divided public participation and planning into three levels: non-participation, tokenism, and citizen power. Harland Bartholomew—first full-time municipally employed planner, St. Louis (1913); developed many early comprehensive plans. Edward Bassett—authored 1916 New York City zoning code. Edward Bennett—plan for San Francisco (1904); worked with Burnham on 1909 plan of Chicago. Alfred Bettman—authored first comprehensive plan: Cincinnati (1925); filed amicus curiae brief in support of Euclid and comprehensive zoning; first president of ASPO. Ernest Burgess—Concentric ring theory (1925)—urban areas grow in a series of concentric rings outward from CBD. Daniel Burnham—City Beautiful movement; White City at 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago; 1909 plan for Chicago, which applied principles of monumental city design and City Beautiful movement. Rachel Carson—brought attention to the negative effects of pesticides on the environment with her book Silent Spring (1962). F. Stuart Chapin—wrote Urban Land Use Planning (1957), a common textbook on land use planning. Paul Davidoff—father of advocacy planning; argued planners should not be value- neutral public servant, but should represent special interest groups. Peter Drucker—created ‘management by objectives’ (MBO), a management process whereby the superior and subordinate jointly identify their common goals, define each individual's major areas of responsibility in terms of the results expected of him, and use these measures as guides for operating the unit and assessing the contribution of each of its members. -

Please Scroll Down for Article

This article was downloaded by: [CDL Journals Account] On: 5 January 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 785022367] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of the American Planning Association Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t782043358 The Metropolitan Dimension of Early Zoning: Revisiting the 1916 New York City Ordinance Raphael Fischler Online Publication Date: 30 June 1998 To cite this Article Fischler, Raphael(1998)'The Metropolitan Dimension of Early Zoning: Revisiting the 1916 New York City Ordinance',Journal of the American Planning Association,64:2,170 — 188 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/01944369808975974 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01944369808975974 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Who Controls the Gold Stealing New York Fed Bank? Presented January 2014 by Charles Savoie “WE HAVE the QUESTION of GOLD UNDER CONSTANT SURVEILLANCE

Who Controls The Gold Stealing New York Fed Bank? Presented January 2014 by Charles Savoie “WE HAVE THE QUESTION OF GOLD UNDER CONSTANT SURVEILLANCE. WE HAVE BEEN UNDER ATTACK BECAUSE OF OUR ATTITUDE TOWARDS GOLD. A FREE GOLD MARKET IS HERESY. THERE IS NO SENSE IN A MAKE BELIEVE FREE GOLD MARKET. GOLD HAS NO USEFUL PURPOSE TO SERVE IN THE POCKETS OF THE PEOPLE. THERE IS NO HIDDEN AGENDA.” ---Pilgrims Society member Allan Sproul, president of Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1941-1956. “ANY ATTEMPT TO WRITE UP THE PRICE OF GOLD WOULD ASSUREDLY BE MATCHED, WITHIN HOURS, BY COMPARABLE AND OFFSETTING ACTION.” ---Robert V. Roosa, Pilgrims Society, in “Monetary Reform for the World Economy” (1965). Roosa was with the New York Federal Reserve Bank, 1946-1960 when he moved to Treasury to fight silver coinage! “The most powerful international society on earth, the “Pilgrims,” is so wrapped in silence that few Americans know even of its existence since 1903.” ---E.C. Knuth, “The Empire of The City: World Superstate” (Milwaukee, 1946), page 9. “A cold blooded attitude is a necessary part of my Midas touch!” ---financier Scott Breckenridge in “The Midas Man,” April 13, 1966 “The Big Valley” The Pilgrims Society is the last great secret of modern history! ******************** Before gold goes berserk like Godzilla rampaging across Tokyo--- and frees silver to supernova---let’s have a look into backgrounds of key Federal Reserve personalities, with special focus on the New York Federal Reserve Bank. The NYFED is the center of an international scandal regarding refusal (incapacity) to return German-owned gold. -

Who Controls the Gold Stealing New York Fed Bank?

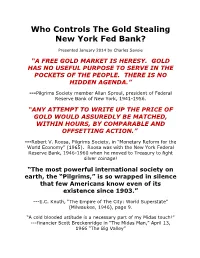

Who Controls The Gold Stealing New York Fed Bank? Presented January 2014 by Charles Savoie “A FREE GOLD MARKET IS HERESY. GOLD HAS NO USEFUL PURPOSE TO SERVE IN THE POCKETS OF THE PEOPLE. THERE IS NO HIDDEN AGENDA.” ---Pilgrims Society member Allan Sproul, president of Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1941-1956. “ANY ATTEMPT TO WRITE UP THE PRICE OF GOLD WOULD ASSUREDLY BE MATCHED, WITHIN HOURS, BY COMPARABLE AND OFFSETTING ACTION.” ---Robert V. Roosa, Pilgrims Society, in “Monetary Reform for the World Economy” (1965). Roosa was with the New York Federal Reserve Bank, 1946-1960 when he moved to Treasury to fight silver coinage! “The most powerful international society on earth, the “Pilgrims,” is so wrapped in silence that few Americans know even of its existence since 1903.” ---E.C. Knuth, “The Empire of The City: World Superstate” (Milwaukee, 1946), page 9. “A cold blooded attitude is a necessary part of my Midas touch!” ---financier Scott Breckenridge in “The Midas Man,” April 13, 1966 “The Big Valley” The Pilgrims Society is the last great secret of modern history! ******************** Before gold goes berserk like Godzilla rampaging across Tokyo--- and frees silver to supernova---let’s have a look into backgrounds of key Federal Reserve personalities, with special focus on the New York Federal Reserve Bank. The NYFED is the center of an international scandal regarding refusal (incapacity) to return German-owned gold. The outrage will worsen. I hope to add to examining this Pandora’s Box of gold suppression by documenting membership of key Fed officials in The Pilgrims Society, which has existed unknown to the public for over a century, and which shoved the world financial system off gold and silver through a series of breathtakingly villainous schemes as profusely documented in http://silverstealers.net/tss.html Just like President Nixon, who stole gold from foreign dollar holders by closing the Treasury gold window, the NYFED is a Pilgrims Society entity. -

SEAGRAM BUILDING, INCWDING the PIAZA, 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan

I.andrnarks Preservation Corrnnission October 3, 1989; resignation List 221 IP-1664 SEAGRAM BUILDING, INCWDING THE PIAZA, 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan. resigned by I.udwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson; Kahn & Jacobs, associate architects. Built 1956-58. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1307, Lot 1. On May 17, 1988, the I.andrnarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a I.andrnark of the Seagram Building including the plaza, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 1) . The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the pro visions of law. 'IWenty-one witnesses, including a representative of the building's owner, spoke in favor of designation. No witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters in favor of designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS Surrnna:ry The Seagram Building, erected in 1956-58, is the only building in New York City designed by architectural master I.udwig Mies van der Rohe. carefully related to the tranquil granite and :marble plaza on its Park Avenue site, the elegant curtain wall of bronze and tinted glass enfolds the first fully modular modern office tower. Constructed at a time when Park Avenue was changing from an exclusive residential thoroughfare to a prestigious business address, the Seagram Building embodies the quest of a successful corporation to establish further its public image through architectural patronage. The president of Joseph E. Seagram & Sons, Samuel Bronfman, with the aid of his daughter Phyllis I.arnbert, carefully selected Mies, assisted by Philip Johnson, to design an office building later regarded by many, including Mies himself, as his crowning work and the apotheosis of International Style towers.