Progress Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

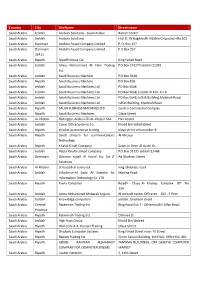

Country City Sitename Street Name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St

Country City SiteName Street name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St. W.Bogddadih AlZabin Cmpound villa 102 Saudi Arabia Damman Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P. O. Box 257 Saudi Arabia Dammam Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P O Box 257 31411 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Riyadh House Est. King Fahad Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Idress Mohammed Ali Fatni Trading P.O.Box 132270 Jeddah 21382 Est. Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machine P.O.Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machine P.O Box 818 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd PO Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Jeddah 21432, K S A Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Juffali Building,Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. Juffali Building, Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Riyadh SAUDI BUSINESS MACHINES LTD. Centria Commercial Complex Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machines Olaya Street Saudi Arabia Al-Khobar Redington Arabia LTD AL-Khobar KSA Hail Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Canar Office Systems Co Khalid Bin Walid Street Saudi Arabia Riyadh shrakat partnerships trading olaya street villa number 8 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Unicom for communications Al-Mrouje technology Saudi Arabia Riyadh Khalid Al Safi Company Salah Al-Deen Al-Ayubi St., Saudi Arabia Jeddah Azizia Panda United Company P.O.Box 33333 Jeddah 21448 Saudi Arabia Dammam Othman Yousif Al Yousif Est. for IT Ad Dhahran Street Solutions Saudi Arabia Al Khober al hasoob al asiavy est. king abdulaziz road Saudi Arabia Jeddah EchoServe-Al Sada Al Shamila for Madina Road Information Technology Co. -

Scholastic Theology (Kalam)

Scholastic Theology (Kalam) Author : Ayatollah Murtadha Mutahhari Introduction Foreword Lesson one : Scholastic Theology Lesson two : Scholastic theology, a definition Lesson three : The Mu'tazilites (1) Lesson four : The Mu'tazilites (2) Lesson five : The Mu'tazilites (3) Lesson six : The Ash'arites Lesson seven : The Shia (1) Lesson eight : The Shia (2) Introduction The linked image cannot be displayed. The file may have been moved, renamed, or deleted. Verify that the link points to the correct file and location. For sometime now, we have been looking at giving the up and coming generation the attention that they deserve. Our aim is to make available to them the sort of things and literature that they identify with and like in different languages, amongst which is English. It is an undeniable fact that English has become the primary language of communication between Presented by http://www.alhassanain.com & http://www.islamicblessings.com our second generations living here in the West. Accordingly, the Alul Bayt (a.s.) Foundation for Reviving the Heritage, London, U.K. has recognised the need for setting up a publishing house whose duty it is to translate the gems of our religious and cultural heritage to the main living languages. After discussing the idea with Hujjatul Islam as‐Sayyid Jawad ash‐ Shahristani, the establishment of Dar Al‐Hadi in London, U.K. has become a reality. It is a known fact that many members of our younger generation aspire to become acquainted with and/or study the different disciplines taught in the conventional centres of religious learning and scholarship. -

Ideological Background of Rationality in Islam

31 Al-Hikmat Volume 28 (2008), pp. 31-56 THE IDEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND OF RATIONALITY IN ISLAM MALIK MUHAMMAD TARIQ* Abstract. Islam the religion of Muslims, founded on Qu’rānic revelations transmitted through the Prophet Muhammad (570-632 AD). The Arabic roots slm, convey the ideas of safety, obedience, submission, commitment, and dedication. The word Islam signifies the self-surrender to Allah that characterizes a Muslim’s relation- ship with God. Islamic tradition records that in 610 and 632 CE Prophet Muhammad began to receive revelations from God through the mediation of Angel Gabriel. The revelations were memorized and recorded word by word, and are today found in Arabic text of the Qur’ān in the precisely the manner God intended.1 The community, working on the basis of pieces of text written ‘on palm leaves or flat stones or in the heart of men’, compiled the text some thirty years after the death of Prophet Muhammad.2 All the Muslims assert unequivocally the divine authorship of the Qur’ān, Muhammad is but the messenger through which it was revealed. Theoretically, the Qur’ān is the primary source of guidance in the Islamic community (Ummah). The Qur’ān text does not, however, provide solutions for every specific problem that might arise. To determine norm of practice, Muslims turned to the lives of Prophet Muhammad and his early companions, preserved in Sunnah, the living tradition of the community. Originally the practicing of Sunnah varied from place to place, reflecting the pre-Islamic local customs of particular region. By the 9th century, however, the diversity evident in local traditions was branded as an innovation (bid’a). -

READ Middle East Brief 101 (PDF)

Judith and Sidney Swartz Director and Professor of Politics Repression and Protest in Saudi Arabia Shai Feldman Associate Director Kristina Cherniahivsky Pascal Menoret Charles (Corky) Goodman Professor of Middle East History and Associate Director for Research few months after 9/11, a Saudi prince working in Naghmeh Sohrabi A government declared during an interview: “We, who Senior Fellow studied in the West, are of course in favor of democracy. As a Abdel Monem Said Aly, PhD matter of fact, we are the only true democrats in this country. Goldman Senior Fellow Khalil Shikaki, PhD But if we give people the right to vote, who do you think they’ll elect? The Islamists. It is not that we don’t want to Myra and Robert Kraft Professor 1 of Arab Politics introduce democracy in Arabia—but would it be reasonable?” Eva Bellin Underlying this position is the assumption that Islamists Henry J. Leir Professor of the Economics of the Middle East are enemies of democracy, even if they use democratic Nader Habibi means to come to power. Perhaps unwittingly, however, the Sylvia K. Hassenfeld Professor prince was also acknowledging the Islamists’ legitimacy, of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies Kanan Makiya as well as the unpopularity of the royal family. The fear of Islamists disrupting Saudi politics has prompted very high Renée and Lester Crown Professor of Modern Middle East Studies levels of repression since the 1979 Iranian revolution and the Pascal Menoret occupation of the Mecca Grand Mosque by an armed Salafi Neubauer Junior Research Fellow group.2 In the past decades, dozens of thousands have been Richard A. -

Jeddah Tower for Web.Indd

Jeddah Tower Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Jeddah Tower Jeddah, Saudi Arabia At over 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) and a total construction area of 530,000 square meters (5.7 million square feet), Jeddah Tower— formerly known as Kingdom Tower—will be the centerpiece and first construction phase of the $20 billion Kingdom City development in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, near the Red Sea. SERVICES Expected to cost $1.2 billion to construct, Jeddah Tower will be a mixed-use building featuring a luxury hotel, office Architecture space, serviced apartments, luxury condominiums and the world’s highest observatory. Jeddah Tower’s height will be Interior Design at least 173 meters (568 feet) taller than Burj Khalifa, which was designed by Adrian Smith while at Skidmore, Owings Master Planning & Merrill. CLIENT AS+GG’s design for Jeddah Tower is both highly technological and distinctly organic. With its slender, subtly Jeddah Economic Company asymmetrical massing, the tower evokes a bundle of leaves shooting up from the ground—a burst of new life that FUNCTION heralds more growth all around it. This symbolizes the tower as a catalyst for increased development around it. Mixed use The sleek, streamlined form of the tower can be interpreted as a reference to the folded fronds of young desert plant FACTS growth. The way the fronds sprout upward from the ground as a single form, then start separating from each other at 1,000+ m height the top, is an analogy of new growth fused with technology. 530,000 sm area While the design is contextual to Saudi Arabia, it also represents an evolution and a refinement of an architectural continuum of skyscraper design. -

Alkhurma Hemorrhagic Fever in Humans, Najran, Saudi Arabia Abdullah G

RESEARCH Alkhurma Hemorrhagic Fever in Humans, Najran, Saudi Arabia Abdullah G. Alzahrani, Hassan M. Al Shaiban, Mohammad A. Al Mazroa, Osama Al-Hayani, Adam MacNeil, Pierre E. Rollin, and Ziad A. Memish Alkhurma virus is a fl avivirus, discovered in 1994 in a district, south of Jeddah (3). Among the 20 patients with person who died of hemorrhagic fever after slaughtering a confi rmed cases, 11 had hemorrhagic manifestations and sheep from the city of Alkhurma, Saudi Arabia. Since then, 5 died. several cases of Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever (ALKHF), Full genome sequencing has indicated that ALKV is with fatality rates up to 25%, have been documented. From a distinct variant of Kyasanur Forest disease virus, a vi- January 1, 2006, through April 1, 2009, active disease sur- rus endemic to the state of Karnataka, India (4). Recently, veillance and serologic testing of household contacts identi- fi ed ALKHF in 28 persons in Najran, Saudi Arabia. For epi- ALKV was found by reverse transcription–PCR in Orni- demiologic comparison, serologic testing of household and thodoros savignyi ticks collected from camels and camel neighborhood controls identifi ed 65 serologically negative resting places in 3 locations in western Saudi Arabia (5). persons. Among ALKHF patients, 11 were hospitalized and ALKHF is thought to be a zoonotic disease, and reservoir 17 had subclinical infection. Univariate analysis indicated hosts may include camels and sheep. Suggested routes of that the following were associated with Alkhurma virus in- transmission are contamination of a skin wound with blood fection: contact with domestic animals, feeding and slaugh- of an infected vertebrate, bite of an infected tick, or drink- tering animals, handling raw meat products, drinking unpas- ing of unpasteurized, contaminated milk (6). -

Online Islamic Da'wah Narratives in the UK: the Case of Iera

Online Islamic Da'wah Narratives in the UK: The Case of iERA by MIRA A. BAZ A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Religion and Theology College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis is an in-depth study into two of the UK charity iERA's da'wah narratives: the Qura'nic embryology 'miracle' and the Kalam Cosmological Argument. While the embryo verses have received scholarly attention, there is little to no research in the da'wah context for both narratives. Berger and Luckmann's social constructionism was applied to both, which were problematic. It was found that iERA constructed its exegesis of the embryo verses by expanding on classical meanings to show harmony with modern science. Additionally, it developed the Cosmological Argument by adapting it to Salafi Islamic beliefs. The construction processes were found to be influenced by an online dialectic between iERA and its Muslim and atheist detractors, causing it to abandon the scientific miracles and modify the Cosmological Argument. -

İbn Hazm'ın Mürcie'den Saydığı Ekollerin İman Tanımlarına

Anemon Muş Alparslan Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 2021 9(İDEKTA) 17-24 Journal of Social Sciences of Mus Alparslan University anemon Derginin ana sayfası: http://dergipark.gov.tr/anemon Araştırma Makalesi ● Research Article İbn Hazm’ın Mürcie’den Saydığı Ekollerin İman Tanımlarına Yönelttiği Eleştiriler* The Criticisim of Ibn Hazm Towards the Definitions of Faith of Theological Ecoles Considered As Murjiah Abdullah ARCAa,** a Dr. Öğr. Üyesi, Muş Alparslan Üniversitesi İslami İlimler Fakültesi, Temel İslam Bilimleri Bölümü, Muş/Türkiye. ORCİD 0000-0003-3064-9647 MAKALE BİLGİSİ ÖZ Makale Geçmişi: Mürcie, kelami bir fırka olarak büyük günah işleyenlerin durumunu Allah’a bırakıp, dini anlamdaki Başvuru tarihi: 30 Mart 2021 sorumlulukları hakkında fikir beyan etmeyen kişilere verilen ortak bir isimdir. Bununla beraber Düzeltme tarihi: 24 Haziran 2021 Mürcie hakkında “amelleri niyet ve inançtan sonraya bırakanlar”, “büyük günah işleyenlere ümit Kabul tarihi: 4 Temmuz 2021 verenler” veya “imanı sırf dille ikrardan ibaret görenler” şeklinde çeşitli isimlendirilmeler de yapılmıştır. İslam kaynaklarında onlardan söz edilirken özellikle iman hakkındaki görüşleri Anahtar Kelimeler: üzerinde durulmuş ve onlara çeşitli eleştiriler yapılmıştır. İbn Hazm, İslami ilimlerde derin bilgi İbn Hazm, sahibi olan Endülüslü Müslüman âlimlerden biridir. Eserlerinde kendi düşüncesine aykırı bulduğu Mürcie, kişi ve fırkaların düşüncelerini eleştirmekten çekinmemiştir. Bu çalışmada İbn Hazm’ın kendi İman iman anlayışına uymayan diğer ekolleri Mürcie’den sayıp -

SHEIKH TAWFIQUE CHOWDHURY Preview Version

Preview Version SHEIKH TAWFIQUE CHOWDHURY Preview Version Importance of this knowledge 1. This knowledge is of the most excellent without any exception. The excellence of any field of study is determined by its subject. The subject studied here is Allah's Names, His Attributes and His actions, which are the greatest matters that can be known, therefore Tawhid of Allah's Names and attributes is the greatest of sciences. Some of the salaf said, “Whoever wishes to know the difference between the speech of the creator and of the creation, should look at the difference between the Creator and the creation themselves.” Different verses in chapters in the Qur'an vary with each other in excellence. This is because of the different subjects they deal with. Surah Al-Ikhlas equals one-third of the Qur'an because it is dedicated to describing Al-Rahman. One of the Salaf said, “Tabbat Yada Abi Lahab” is not like “Qul Huwallhu Ahad”. Ayat Al-Kursi is the greatest Ayah in the Qur'an as it is devoted to describing Allah, His Majesty and Greatness. Likewise Al-Fatiha is the greatest Sura in the Qur'an. It is based on the praise of Allah. 2. Teaching Allah's Names and Attributes is one of the greatest goals of the Qur'an The Quran in its entirety is simply a call to Tawheed. Ibn Al- Qayyim stated, “Every Sura in the Qur'an comprises Tawhid. In fact, I shall state an absolute: Every verse in the Qur'an comprises Tawhid, attests to it, and calls to it. -

ISLAMIC FOUNDATIONS of a FREE SOCIETY

ISLAMIC FOUNDATIONS of a FREE SOCIETY Edited by NOUH EL HARMOUZI & LINDA WHETSTONE Islamic Foundations of a Free Society ISLAMIC FOUNDATIONS OF A FREE SOCIETY EDITED BY NOUH EL HARMOUZI AND LINDA WHETSTONE with contributions from MUSTAFA ACAR • SOUAD ADNANE AZHAR ASLAM • HASAN YÜCEL BAŞDEMIR KATHYA BERRADA • MASZLEE MALIK • YOUCEF MAOUCHI HICHAM EL MOUSSAOUI • M. A. MUQTEDAR KHAN BICAN ŞAHIN • ATILLA YAYLA First published in Great Britain in 2016 by The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Westminster London SW1P 3LB in association with London Publishing Partnership Ltd www.londonpublishingpartnership.co.uk The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society by analysing and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2016 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-255-36729-5 (interactive PDF) Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or -

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Etc. : Feasibility Study for Diffusion of the Water Reclamation System)

FY2018 Feasibility Study Report for Overseas Deployment of High Quality Infrastructure System (the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, etc. : Feasibility Study for Diffusion of the Water Reclamation System) March 2019 Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry Contractor : Kobelco Eco-Solutions Co., Ltd. Chiyoda Corporation Sankyu Inc. Introduction The Saudi government has set out “Saudi Vision 2030,” a growth strategy to achieve comprehensive development independently of oil dependency. Our country, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, formulated and announced in 2017 “Japan-Saudi Vision 2030” with the basic directionality of bilateral cooperation and the concrete project list. Under the vision, high-quality water infrastructure is a key area for cooperation between the two countries, and a memorandum of cooperation on seawater desalination and RO reclaimed water has been signed between the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture of Saudi Arabia. In the memorandum, the promotion of the demonstration project of reclaimed water system in Dammam I of Saudi Industrial Property Authority (MODON) and the diffusion of the technology are mentioned. Based on the results of implementation of the demonstration project in Dammam I, the feasibility of application of reclaimed water system (which produces the RO reclaimed water by way of biological and membrane treatment) to the countries such as Saudi Arabia shall be studied in this project from the viewpoints of market, technology and policy in accordance with the memorandum of understanding entered into between MODON and the consortium (Chiyoda Corporation and Kobelco Eco-Solutions Co., Ltd.). In this project, after conducting the market survey research on the business environment and potential customers in Saudi Arabia, etc, we examined the technical application of the reclaimed water system. -

Historic Jeddah, the Gate to Makkah

Historic Jeddah, the Gate to Makkah Report on the State of Conservation of the Property KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage Historic Jeddah, the Gate of Makkah State of Conservation Report November 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In the past two years, following the inscription of Historic Jeddah, the Gate to Makkah on the UNESCO World Heritage List, the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage and the Municipality of Jeddah have been actively implementing the strategy presented in the Nomination File and in the Action Plan submitted to UNESCO. A series of major results has already been achieved since the inscription: - The approval of the new Saudi Antiquities, Museums and Urban Heritage Law, in July 2014 immediately after the inscription of the property on the UNESCO World Heritage List provides the essential legal framework to allow the implementation of the revitalization plans; - Preparation of new Building Regulation for the historic area. The regulation, designed in the framework of the nomination process to guide and control the conservation and revitalization of the site, has been formally approved by the Municipality of Jeddah in 2015 and is now legally enforced on the field; - The inventory of all historic buildings has also been completed. It provides the basis for the design of a sound strategy for the conservation and re-use of historic buildings; - These two essential tools permit the work of the technical and administrative teams of SCTH and Jeddah Municipality on the field; - The monitoring mechanisms and the coordination between the two teams are now in place and local and international experts are actively involved in the daily monitoring and protection of the property; and - In the meantime, cultural initiatives focusing on the city's heritage have taken place creating a renewed attention in Jeddah residents for their history and their city.