Where the Lord Sleeps Author: Neela Padmanabhan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Sahitya Akademi Translation Prize 2013

DELHI SAHITYA AKADEMI TRANSLATION PRIZE 2013 August 22, 2014, Guwahati Translation is one area that has been by and large neglected hitherto by the literary community world over and it is time others too emulate the work of the Akademi in this regard and promote translations. For, translations in addition to their role of carrying creative literature beyond known boundaries also act as rebirth of the original creative writings. Also translation, especially of ahitya Akademi’s Translation Prizes for 2013 were poems, supply to other literary traditions crafts, tools presented at a grand ceremony held at Pragyajyoti and rhythms hitherto unknown to them. He cited several SAuditorium, ITA Centre for Performing Arts, examples from Hindi poetry and their transportation Guwahati on August 22, 2014. Sahitya Akademi and into English. Jnanpith Award winner Dr Kedarnath Singh graced the occasion as a Chief Guest and Dr Vishwanath Prasad Sahitya Akademi and Jnanpith Award winner, Dr Tiwari, President, Sahitya Akademi presided over and Kedarnath Singh, in his address, spoke at length about distributed the prizes and cheques to the award winning the role and place of translations in any given literature. translators. He was very happy that the Akademi is recognizing Dr K. Sreenivasarao welcomed the Chief Guest, and celebrating the translators and translations and participants, award winning translators and other also financial incentives are available now a days to the literary connoisseurs who attended the ceremony. He translators. He also enumerated how the translations spoke at length about various efforts and programmes widened the horizons his own life and enriched his of the Akademi to promote literature through India and literary career. -

Location Accessibility

Panchayat/ Municipality/ Thiruvananthapuram Corporation Corporation LOCATION District Thiruvananthapuram Nearest Town/ East Fort – 200 m Landmark/ Junction Nearest Bus statio East Fort Bus Stand – 200 m Nearest Railway Trivandrum Central Railway Station – 1.4 Km statio ACCESSIBILITY Nearest Airport Trivandrum International Airport – 4.1 Km The Executive Officer Mathilakam Office, West Nada Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple East Fort, Thiruvananthapuram -695023 Phone: +91-471-2450233 +91-471-2466830 (Temple) CONTACT +91-471-2464606 (Helpline) Email: [email protected] Website: www.sreepadmanabhaswamytemple.org DATES FREQUENCY DURATION TIME October – November (Thulam) Annual 10 Days ABOUT THE FESTIVAL (Legend/History/Myth) The festival is a ritualistic and colourful celebration at the Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple. Ritualistic circumambulations in different kinds of vehicles called Vahanams are an important part of the festivities. In olden times, idols were carried by elephants, however, the practice was given up after an elephant ran amok. Now, a number of priests carry the idols in special Vahanams placed on their shoulders. Six kinds of vehicles are used for these processions. These are the Simhasana Vahanam (Throne), Anantha Vahanam (Serpent), Kamala Vahanam (Lotus), Pallakku Vahanam (Palanquin), Garuda Vahanam (Garuda) and Indra Vahanam (Gopuram). Of these , the Pallakku and Garuda Vahanas are repeated twice and four times respectively. The Garuda Vahanam is considered as the favourite conveyance of the Lord. The different days on which the Vahanams are taken out for procession are as follows: Simhasana Vahanam, Anantha Vahanam, Kamala Vahanam, Pallakku Vahanam, Garuda Vahanam, Indra Vahanam, Pallakku Vahanam and Garuda Vahanam on the following days. Sree Padmanabhaswamy’s Vahanam is in gold while Narayana Swamy’s and Sree Krishna Swamy’s Vahanas are in silver. -

List of Documentaries Produced by Sahitya Akademi

LIST OF DOCUMENTARIES PRODUCED BY SAHITYA AKADEMI S.No.AuthorDirected byDuration 1. Amrita Pritam (Punjabi) Basu Bhattacharya 60 minutes 2. Akhtar-ul-Iman (Urdu) Saeed Mirza 60 minutes 3. V.K. Gokak (Kannada) Prasanna 60 minutes 4. ThakazhiSivasankara Pillai (Malayalam) M.T. Vasudevan Nair 60 minutes 5. Gopala krishnaAdiga (Kannada) Girish Karnad 60 minutes 6. Vishnu Prabhakar (Hindi) Padma Sachdev 60 minutes 7. Balamani Amma (Malayalam) Madhusudanan 27 minutes 8. VindaKarandikar (Marathi) Nandan Kudhyadi 60 minutes 9. Annada Sankar Ray (Bengali) Budhadev Dasgupta 60 minutes 10. P.T. Narasimhachar (Kannada) Chandrasekhar Kambar 27 minutes 11. Baba Nagarjun (Hindi) Deepak Roy 27 minutes 12. Dharamvir Bharti (Hindi) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 13. D. Jayakanthan (Tamil) Sa. Kandasamy 27 minutes 14. Narayan Surve (Marathi) DilipChitre 27 minutes 15. BhishamSahni (Hindi) Nandan Kudhyadi 27 minutes 16. Subhash Mukhopadhyay (Bengali) Raja Sen 27 minutes 17. TarashankarBandhopadhyay(Bengali)Amiya Chattopadhyay 27 minutes 18. VijaydanDetha (Rajasthani) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 19. NavakantaBarua (Assamese) Gautam Bora 27 minutes 20. Mulk Raj Anand (English) Suresh Kohli 27 minutes 21. Gopal Chhotray (Oriya) Jugal Debata 27 minutes 22. QurratulainHyder (Urdu) Mazhar Q. Kamran 27 minutes 23. U.R. Anantha Murthy (Kannada) Krishna Masadi 27 minutes 24. V.M. Basheer (Malayalam) M.A. Rahman 27 minutes 25. Rajendra Shah (Gujarati) Paresh Naik 27 minutes 26. Ale Ahmed Suroor (Urdu) Anwar Jamal 27 minutes 27. Trilochan Shastri (Hindi) Satya Prakash 27 minutes 28. Rehman Rahi (Kashmiri) M.K. Raina 27 minutes 29. Subramaniam Bharati (Tamil) Soudhamini 27 minutes 30. O.V. Vijayan (Malayalam) K.M. Madhusudhanan 27 minutes 31. Syed Abdul Malik (Assamese) Dara Ahmed 27 minutes 32. -

Reportable in the Supreme Court of India Civil

Civil Appeal No. 2732 of 2020 (arising out of SLP(C)No.11295 of 2011) etc. Sri Marthanda Varma (D) Thr. LRs. & Anr. vs. State of Kerala and ors. 1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE/CIVIL ORIGINAL/INHERENT JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NO.2732 OF 2020 [Arising Out of Special Leave Petition (C) No.11295 of 2011] SRI MARTHANDA VARMA (D) THR. LRs. & ANR. …Appellants VERSUS STATE OF KERALA & ORS. …Respondents WITH CIVIL APPEAL NO. 2733 OF 2020 [Arising Out of Special Leave Petition (C) No.12361 of 2011] AND WRIT PETITION(C) No.518 OF 2011 AND CONMT. PET.(C) No.493 OF 2019 IN SLP(C) No.12361 OF 2011 Civil Appeal No. 2732 of 2020 (arising out of SLP(C)No.11295 of 2011) etc. Sri Marthanda Varma (D) Thr. LRs. & Anr. vs. State of Kerala and ors. 2 J U D G M E N T Uday Umesh Lalit, J. 1. Leave granted in Special Leave Petition (Civil) No.11295 of 2011 and Special Leave Petition (Civil) No.12361 of 2011. 2. Sree Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma who as Ruler of Covenanting State of Travancore had entered into a Covenant in May 1949 with the Government of India leading to the formation of the United State of Travancore and Cochin, died on 19.07.1991. His younger brother Uthradam Thirunal Marthanda Varma and the Executive Officer of Sri Padmanabhaswamy Temple, Thiruvananthapuram (hereinafter referred to as ‘the Temple’) as appellants 1 and 2 respectively have filed these appeals challenging the judgment and order dated 31.01.2011 passed by the High Court1 in Writ Petition (Civil) No.36487 of 2009 and in Writ Petition (Civil) No.4256 of 2010. -

Academic Curriculum Vitae Marie Josephine Aruna Assistant Professor Department of English Kanchi Mamunivar Government Instit

Academic Curriculum Vitae Marie Josephine Aruna Assistant Professor Department of English Kanchi Mamunivar Government Institute for Postgraduate Studies and Research (Autonomous) Govt. of Puducherry Puducherry-605008, India. / kmcpgs.puducherry.gov.in/ Email: [email protected] Mobile: 9442234350 Qualifications Ph.D. English Pondicherry Central University Thesis- Patriarchal Myths in Postmodern Feminist Fiction: A Select Study January 2011 M.Phil. English Pondicherry Central University Thesis- Existential Critique of Marriage: A Comparative Study of Select Novels of Simone De Beauvoir and Nayantara Sahgal April 1991 M.A. English and Comparative Literature Pondicherry Central University Project – Idayanaadam and A Portrait of The Artist As A Young Man as Bildungsromane April 1990 M.A. Women’s Studies Allagappa University Karaikudi, Tamilnadu May 2004 P.G. Diploma in Higher Education Indira Gandhi National Open University New Delhi June 2000 P.G. Diploma in Journalism and Mass Communications Pondicherry University Community College Pondicherry Central University September 1998 Research Profile Member of several peer-reviewed online and print journals for which regular contributions are made, I am interested in employing theoretical/critical approaches to literary texts as methods of analysis. Recognized Guide (Full Time/ Part Time PhD) for Pondicherry Central University, Pondicherry. Recognized Guide for Bharathiar University (Part-Time PhD) and currently supervising two PhD candidates registered under Bharathiar University, Coimbatore. PhD/M.Phil Candidates 1 -PhD Candidate Awarded– Bharathiar University (Part-Time PhD) 6th July 2018 1-M.Phil Candidate (Pondicherry University)-KMCPGS- (2017-18 Batch) – Awarded-25/01 2019 2--M.Phil Candidates (2018-19 Batch), Awarded -11/01/2020 2-PhD Candidates – (Pondicherry University- 2018-19 & 2019-20 Batches)-KMGIPSR- ongoing. -

Chevalior Sivaji Ganesan‟S Tamil Film Songs Not Only Emulated the Quality of the Movie but Also Contains Ethical Imports That

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: A Arts & Humanities - Psychology Volume 20 Issue 10 Version 1.0 Year 2020 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Chevalior Sivaji Ganesan‟S Tamil Film Songs Not Only Emulated the Quality of the Movie but also Contains Ethical Imports that can be Compared with the Ethical Theories – A Retrospective Reflection By P.Sarvaharana, Dr. S.Manikandan & Dr. P.Thiyagarajan Tamil Nadu Open University Abstract- This is a research work that discusses the great contributions made by Chevalior Shivaji Ganesan to the Tamil Cinema. It was observed that Chevalior Sivaji film songs reflect the theoretical domain such as (i) equity and social justice and (ii) the practice of virtue in the society. In this research work attention has been made to conceptualize the ethical ideas and compare it with the ethical theories using a novel methodology wherein the ideas contained in the film song are compared with the ethical theory. Few songs with the uncompromising premise of patni (chastity of women) with the four important charateristics of women of Tamil culture i.e. acham, madam, nanam and payirpu that leads to the great concept of chastity practiced by exalting woman like Kannagi has also been dealt with. The ethical ideas that contain in the selection of songs were made out from the selected movies acted by Chevalier Shivaji giving preference to the songs that contain the above unique concept of ethics. GJHSS-A Classification: FOR Code: 190399 ChevaliorSivajiGanesanSTamilFilmSongsNotOnlyEmulatedtheQualityoftheMoviebutalsoContainsEthicalImportsthatcanbeComparedwiththeEthicalTheo riesARetrospectiveReflection Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2020. -

IEPF-2 Disclosures FY-17-18

TCP Ltd Details of Unclaimed deposits as at the 46th AGM date 26-10-18 For the Financial year ended 31-3-18 (1st Year for IEPF Rule 5 (8) compliance) Unclaimed position as at the 46th AGM held on 26-10-18 - 1st year intimation (the unclaimed status details of the following depositors shall be furnished as at the closure of each of the succeeding 7 AGM's up to the AGM held for the Financial year ended 31-3-25) For the purpose of filing Form IEPF-2 And thereafter it should be remitted to the IEPF within 30 days from the due date Fixed Deposit Serial No. Name Address Nature of Amount Amount Rs. Due date for transfer FDR No. to the IEPF 1 Rajalakshmi Natarajan 28/2, Lakshmi Colony, T. Nagar, Matured deposit 10,000 12/6/2017 16376 Chennai 600017 2 P. Eswaramurthy Old No.36, New No.54, Krishnappa Matured deposit 10,000 5/1/2018 16517 Agraharam Street, Chennai 600079 3 N. Krishna Kumar New No.10, Old No.41, IInd Street, Matured deposit 20,000 8/17/2018 16908 Parthasarathy Nagar, Adambakkam, Chennai 600088 4 L. Janaki 23/48, Rani Anna Nagar, Matured deposit 20,000 9/3/2018 16989 K K Nagar, Chennai 600078 5 Nalini R Pai No.13, A G Colony, Matured deposit 16,000 3/14/2019 17428 Alwar Thirunagar, Chennai 600087 6 P. Ravisekar 24/19, Second Main Road, J B Estate Matured deposit 10,000 11/23/2019 18311 Avadi, Chennai 600054 7 Vasantha Ravindran 1 Sri Devi Apartments, Matured deposit 25,000 5/23/2020 18638 5/2, 4th Trust Cross Street, Mandaveli, Chennai 600028 8 Hemlatha D Tarvady Shri Shraddha', 5/2A, Dr. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

The Padmanabhaswamy Temple Case

The Padmanabhaswamy Temple Case drishtiias.com/printpdf/the-padmanabhaswamy-temple-case Why in News Recently, the Supreme Court of India upheld the right of the Travancore royal family to manage the property of deity at Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala). The Temple has been in the news since 2011 after the discovery of treasure worth over Rs. 1 lakh crore in its underground vaults. Key Points 1/3 Judgement: The Supreme Court (SC) reversed the 2011 Kerala High Court decision, which had directed the Kerala government to set up a trust to control the management and assets of the temple. The High Court (HC) had ruled that the successor to the erstwhile royals could not claim to be in control of the Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple after the amendment of definition of ‘Ruler’ in Article 366 (22) of the Constitution of India. The definition of Ruler was amended by the Twenty Sixth (Constitutional) Amendment Act, 1971, which abolished the privy purses. Article 366 (22) reads, “Ruler” means the Prince, Chief or other person who, at any time before the commencement of the Twenty Sixth (Constitutional) Amendment Act, 1971, was recognised as the Ruler of an Indian State or was recognised as the successor of such Ruler. However, the SC rejected this and said that, as per customary law, the members of the royal family have the shebait rights even after the death of the last ruler. Shebait rights means right to manage the financial affairs of the deity. The SC held that, for the purpose of shebait rights the definition of Ruler would apply and would transfer to the successor. -

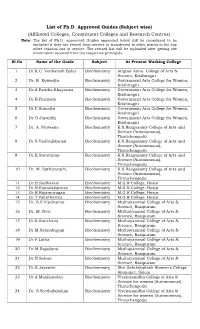

List of Ph.D. Approved Guides (Subject Wise)

List of Ph.D. Approved Guide s ( Subject w ise) (Affiliated Colleges, Constituent Colleges and Research Centres) Note: The list of Ph.D. apporoved Guides appended below will be considered to be excluded if they are retired from secvice or transferred to other places or for any other reasons not in service. The revised list will be uploaded after getting the information re ceived from the respective principals. Sl.No Name of the Guide Subject At Present Working College 1 Dr.K.C. Venkatesh Babu Biochemistry Arignar Anna College of Arts & Science, Krishnagiri 2 Dr. R. Kowsalya Biochemistry G overnment Arts College for Women, Krishnagiri 3 Dr.A.Paritha Ithayarasi Biochemistry G overnment Arts College for Women, Krishnagiri 4 Dr.R.Parimala Biochemistry G overnment Arts College for Women, Krishnagiri 5 Dr.P.Sumathi Biochemistry G overnment Arts College for Women, Krishnagiri 6 Dr.G.Jayanthi Biochemistry G overnment Arts College for Women, Krishnagiri 7 Dr. A. Praveena Biochemistry K. S.Rangasa m y College of Arts and Science (Autonomous), Thiruchengodu 8 Dr.S.Vadivukkarasi Biochemistry K. S.Rangasa m y College of Arts and Science (Autonomous), Thiruchengodu 9 Dr.K.Saravanan Biochemistry K. S.Rangasa m y College of Arts and Science (Autonomous), Thiruchengodu 10 Dr. M. Sathiyavathi, Biochemistry K. S.Rangasa m y College of Arts and Science (Autonomous), Thiruchengodu 11 Dr.B.Sudharani Biochemistry M.G.R College , Hosur 12 Dr.N.Kamalakannan Biochemistry M.G.R College , Hosur 13 Dr.R.Rajamurugan Biochemistry M.G.R College , Hosur 14 Dr.T.Pakutharivu Biochemistry M.G.R College , Hosur 15 Dr.