Sp. Issue/2015 STUDIA UNIVERSITATIS BABEŞ-BOLYAI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Good Life Edited by Ian Christie and Lindsay Nash

The Good Life Edited by Ian Christie and Lindsay Nash Open access. Some rights reserved. As the publisher of this work, Demos has an open access policy which enables anyone to access our content electronically without charge. We want to encourage the circulation of our work as widely as possible without affecting the ownership of the copyright, which remains with the copyright holder. Users are welcome to download, save, perform or distribute this work electronically or in any other format, including in foreign language translation without written permission subject to the conditions set out in the Demos open access licence which you can read here. Please read and consider the full licence. The following are some of the conditions imposed by the licence: • Demos and the author(s) are credited; • The Demos website address (www.demos.co.uk) is published together with a copy of this policy statement in a prominent position; • The text is not altered and is used in full (the use of extracts under existing fair usage rights is not affected by this condition); • The work is not resold; • A copy of the work or link to its use online is sent to the address below for our archive. By downloading publications, you are confirming that you have read and accepted the terms of the Demos open access licence. Copyright Department Demos Elizabeth House 39 York Road London SE1 7NQ United Kingdom [email protected] You are welcome to ask for permission to use this work for purposes other than those covered by the Demos open access licence. -

Documente Muzicale Tipărite Şi Audiovizuale

BIBLIOTECA NAŢIONALĂ A ROMÂNIEI BIBLIOGRAFIA NA ŢIONALĂ ROMÂNĂ Documente muzicale tipărite şi audiovizuale Bibliografie elaborată pe baza publicaţiilor din Depozitul Legal Anul XLVII 2014 Editura Bibliotecii Naţionale a României BIBLIOGRAFIA NAŢIONALĂ ROMÂNĂ SERII ŞI PERIODICITATE Cărţi. Albume. Hărţi: bilunar Documente muzicale tipărite şi audiovizuale : anual Articole din publicaţii seriale. Cultură: lunar Publicaţii seriale: anual Românica: anual Teze de doctorat: semestrial © Copyright 2014 Toate drepturile sunt rezervate Editurii Bibliotecii Naţionale a României. Nicio parte din această lucrare nu poate fi reprodusă sub nicio formă, prin mijloc mecanic sau electronic sau stocat într-o bază de date, fără acordul prealabil, în scris, al redacţiei. Înlocuieşte seria Note muzicale. Discuri. Casete Redactor: Raluca Bucinschi Coperta: Constantin Aurelian Popovici Lista pubLicaţiiLor bibLiotecii NaţioNaLe a româNiei - Bibliografia Naţională Română seria: Cărţi.Albume.Hărţi seria: Documente muzicale tipărite şi audiovizuale : anual seria: Articole din publicaţii periodice. Cultură: lunar seria: Publicaţii seriale: anual seria: Românica: anual seria: Teze de doctorat: semestrial - Aniversări culturale, 2/an - Biblioteconomie: sinteze, metodologii, traduceri , 2/an - Abstracte în bibliologie şi ştiinţa informării, 2/an - Bibliografia cărţilor în curs de apariţie (CIP), 12/an - Revista Bibliotecii Naţionale a României, 2/an - Revista română de istorie a cărţii, 1/an - Revista română de conservare și restaurare a cărții, 1/an Abonamentele la publicaţiile Bibliotecii Naţionale a României se pot face prin Biblioteca Naţională a României , biroul Editorial (telefon 021 314.24.34/1095) Editura Bibliotecii Naţionale a României Blv. Unirii, nr.22, sect. 3, Bucureşti, cod 030833 Tel.021 314.24.34; Fax:021 312.33.81 E-mail: [email protected] Documente muzicale tipărite şi audiovizuale 3 CUPRINS COMPACT DISCURI - Listă divizionare .......................................................... -

Faire-Valoir Et Seconds Couteaux Sidekicks and Underlings

Essais Revue interdisciplinaire d’Humanités 10 | 2016 Faire-valoir et seconds couteaux Sidekicks and Underlings Nathalie Jaëck et Jean-Paul Gabilliet (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/essais/3692 DOI : 10.4000/essais.3692 ISSN : 2276-0970 Éditeur École doctorale Montaigne Humanités Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 septembre 2016 ISBN : 978-2-9544269-9-0 ISSN : 2417-4211 Référence électronique Nathalie Jaëck et Jean-Paul Gabilliet (dir.), Essais, 10 | 2016, « Faire-valoir et seconds couteaux » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 15 octobre 2020, consulté le 21 octobre 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/essais/3692 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/essais.3692 Essais Revue interdisciplinaire d’Humanités Faire-valoir et seconds couteaux Sidekicks and Underlings Études réunies par Nathalie Jaëck et Jean-Paul Gabilliet Numéro 10 - 2016 (1 - 2016) ÉCOLE DOCTORALE MONTAIGNE-HUMANITÉS Comité de rédaction Jean-Luc Bergey, Laetitia Biscarrat, Charlotte Blanc, Fanny Blin, Brice Chamouleau, Antonin Congy, Marco Conti, Laurent Coste, Hélène Crombet, Jean-Paul Engélibert, Rime Fetnan, Magali Fourgnaud, Jean-Paul Gabilliet, Stanislas Gauthier, Aubin Gonzalez, Bertrand Guest, Sandro Landi, Sandra Lemeilleur, Mathilde Lerenard, Maria Caterina Manes Gallo, Nina Mansion, Mélanie Mauvoisin, Myriam Metayer, Isabelle Poulin, Anne-Laure Rebreyend, Jeffrey Swartwood, François Trahais Comité scientifique Anne-Emmanuelle Berger (Université Paris 8), Patrick Boucheron (Collège de France), Jean Boutier (EHESS), Catherine Coquio (université Paris 7), Phillipe Desan (University of Chicago), Javier Fernandez Sebastian (UPV), Carlo Ginzburg (UCLA et Scuola Normale Superiore, Pise), German Labrador Mendez (Princeton University), Hélène Merlin-Kajman (Université Paris 3), Franco Pierno (Victoria University in Toronto), Dominique Rabaté (Université Paris 7), Charles Walton (University of Warwick) Directeur de publication Sandro Landi Secrétaire de rédaction Chantal Duthu Les articles publiés par Essais sont des textes originaux. -

July 2019 New Releases a JOHN HUGHES FILM a JOHN HUGHES

July 2019 New Releases A JOHN HUGHES FILMILM what’s PAGE inside featured exclusives 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 68 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 11 FEATURED RELEASES JERRY LEE LEWIS - PERE UBU - THE PRETENDERS - THE KNOX PHILLIPS... LONG GOODBYE WITH FRIENDS Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 37 Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 41 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 67 Order Form 74 Deletions and Price Changes 72 BONG OF THE LIVING WEIRD SCIENCE SHORTCUT TO 800.888.0486 DEAD (STEELBOOK) HAPPINESS 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 SEX AND BROADCASTING: JERRY LEE LEWIS - PERE UBU - www.MVDb2b.com A FILM ABOUT WFMU THE KNOX PHILLIPS SESSIONS: LONG GOODBYE (DVD/BOOK/7 INCH VINYL) THE UNRELEASED RECORDINGS KEEP MVD WEIRD! MVD’s quest for weird is never in question, that’s for sure! This month we unveil another in ARROW VIDEO’s spectacular deluxe versions of classic cult films with WEIRD SCIENCE. Director John Hughes offers a hefty dose of wacked-out Sci-Fi in this 1985 film starring Kelly LeBrock and Robert Downey Jr. Being a nerd isn’t so weird after Superwoman appears! Also available as a limited edition Steelbook. This summer, get blinded by WEIRD SCIENCE! A sharp month for Arrow, with their redux of the 1978 rock movie FM, depicting the glory days of free form radio. Stars Martin Mull and Cleavon Little. Corporate greed infiltrates the airwaves, followed by rock and roll rebellion! Infectious soundtrack, featuring several surviving dinosaurs. Tune in, but don’t tune out these other Arrow darts, including THE CHILL FACTOR (“snow, slaughter and Satan!”), THE LOVELESS (starring Willem Dafoe), and the drama of Olivia de Havilland in 1941’s HOLD BACK THE DAWN. -

Tarsem Julia Roberts Lily Collins Armie

Relativity Media presenta in associazione con Yuk Films Una produzione Goldmann Pictures Relativity Media Rat Entertainment Misher Films Un film di Tarsem Julia Roberts in con Lily Collins Armie Hammer Nathan Lane e Mare Winningham Michael Lerner Sean Bean Un’esclusiva per l’Italia Rai Cinema Distribuzione Durata: 105’ Uscita: 4 Aprile 2012 Ufficio stampa film: Ufficio stampa 01 DISTRIBUTION: Ornato Comunicazione Tel. + 39 06684701 Tel. +39.06.3341017 Annalisa Paolicchi [email protected] [email protected] Rebecca Roviglioni [email protected] www.ornatocomunicazione.it Cristiana Trotta [email protected] I MATERIALI STAMPA SONO DISPONIBILI SUL SITO: www.01distribution.it Crediti non contrattuali CAST TECNICO Regia Tarsem Singh Dhand War Sceneggiatura Melisa Wallack e Jason Keller Direttore della fotografia Brendan Galvin Scenografie Tom Foden Montaggio Nick Moore Robert Duffy Costumi Eiko Ishioka Musiche di Alan Menken Supervisori alle musiche Happy Walters Bob Bowen Colorist Lionel Kopp Supervisori effetti visivi Tom Wood Casting Kerry Barden Paul Schnee Produttori esecutivi Tucker Tooley Kevin Misher Jeff Waxman Robbie Brenner Jamie Marshall Jason Colbeck Tommy Turtle Josh Pate John Cheng Coproduttori Kenneth Halsband Nico Soultanakis Agit Singh Prodotto da Bernie Goldmann Ryan Kavanaugh Brett Ratner Un’esclusiva per l’Italia Rai Cinema Distribuzione italiana 01 Distribution Crediti non contratuali 2 CAST ARTISTICO La Regina Julia Roberts Biancaneve Lily Collins Principe Alcott Armie Hammer Brighton Nathan Lane Margaret Mare Winningham Il Barone Michael Lerner Charles Renbock Robert Emms Il Re Sean Bean Napoleon Jordan Prentice Half-Pint Mark Povinelli Grub Joe Gnoffo Grimm Danny Woodburn Wolf Sebastian Saraceno Butcher Martin Klebba Chuckles Ronald Lee Clark Crediti non contratuali 3 SINOSSI Dopo la scomparsa dell’amatissimo Re (Sean Bean), la perfida moglie (Julia Roberts) assume il controllo del regno e tiene la bellissima figliastra diciottenne, Biancaneve (Lily Collins), rinchiusa nel palazzo. -

Newsletter 07/09 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 07/09 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 249 - April 2009 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 07/09 (Nr. 249) April 2009 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD- nen zu bevorstehenden DVD-Ver- Fans, liebe Filmfreunde! öffentlichungen? Sie finden sie Über Ostern haben Sie es ja (hof- hier! Ausgabe 249 erreicht Sie fentlich) wieder reaktiviert: das zwar mit ein wenig Verspätung, Suchen und Finden. Und genau doch dafür mit umfangreichem re- diese Fähigkeit dürfen Sie jetzt daktionellen Teil. Nicht nur ist bei erneut in der vorliegenden Ausgabe unserer Kolumnistin Anna der unseres Newsletters anwenden. Frühling ausgebrochen, der sie zu Sie suchen nach neuen Informatio- neuen Sehgewohnheiten zu verfüh- ren scheint, auch unser Filmblogger Wolfram Hannemann bekennt sich erneut zur Filmsucht in seinem ausführlichen Report zum “Widescreen Weekend” in Bradford, England. Abgerundet wird der kleingedruckte Lesestoff durch die drei Filmeinführungen, die unser Festivaldauergast eigens für Bradford verfasst hat. Diese haben wir in ihrer Originalform be- lassen: ungekürzt und auf Englisch! Gleich im Anschluss daran erfahren Sie dann alles Wichtige zu DVD- und Blu-ray Releases in Deutsch- land, den USA und Japan – ganz so, wie Sie es schon immer ge- wohnt sind. Viel Spaß dabei! Ihr Laser Hotline Team Kurz nach Redaktionsschluss erreichte uns noch diese Meldung: Tom Tykwers THE INTERNATIONAL wird in den USA am 09. Juni 2009 auf DVD und Blu-ray Disc veröffentlicht. -

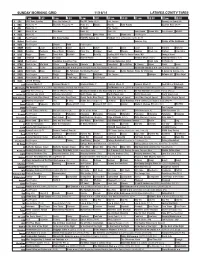

Sunday Morning Grid 11/16/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/16/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Courage in Sports (N) 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Noodle Noodle Auto Racing Spartan Race (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Program Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football 49ers at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Veterans Day Pirates of the Caribbean 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healing ADD With Dr. Daniel Amen, MD Younger Heart 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Premios Bandamax 2014 Hotel Todo Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Superman Returns ››› (2006) Brandon Routh, Kate Bosworth. -

Theories on Drug Abuse: Selected,Contemporary

DOCUMENT RESUME \E11.203 259- CG 015 242. AUTHOR Lettieri, Dan J., Ed.: And Others TITLE Theories on Drug Abuse: Selected,Contemporary Berspectives.; Research Monograph 30. ' INSTITUTION Metrotec Research Associates, Washington, D.C. '.SPONS AGENCY National inst. on DrUg Abuse (DHHS), Rockville, Md. Div. of Research, REPORT NO , ADM-B0-967 ,l PUB DATE,. Mat 90 CONTRACT ADM-271-7973625 NOTE, 526p. AVAI'LABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. FARE PRICE MF027PC22 Pius. 'Postage. DESCRIPTORS Pnthologies: *Prua rrug Addiction: g Edutation: Family Influence:illegal Drug Use Ind viduai Characteristics: *interpersonal Relationship:, loPersonality Traits; *PsychOlogical Patterns: Self Esteem: *Social Influences: *Theories: Youth Problems ABSTRACT This volume presents various theoreticalOrientations and perspectives, of the drug abuse research field, derived frOm. the social and biothedical sciences. The first section contains a separate theoretical overview.for.each of the 43 theories or perspectives. The second section contains five chapters which correspond:_to the five components of a drUg abuie theory, i.e., initiation, continuation, transition and use to abuse, cessation, and relapse. A series of guides, devised tofacilitate comparison and contrast of the theories, lists: '01 all contributing theorists and their professional affiliations`: (2) classifications of the theories into' fourcategories ofone'sfaationship- to ,self,', to others, to.society, and to nature:: (31, identificationsof -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses If no Divells, no God: Devils, D(a)emons and Humankind on the Mediaeval and Early Modern English Stage. BOCK, EMMANUEL How to cite: BOCK, EMMANUEL (2010) If no Divells, no God: Devils, D(a)emons and Humankind on the Mediaeval and Early Modern English Stage., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/750/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Emmanuel Bock “If no Divells, no God”: Devils, D(a)emons and Humankind on the Mediaeval and Early Modern English Stage. Abstract This thesis looks at the relationship that humanity has with the devil, the demonic, and the daemonic as it is represented in plays from the mediaeval to the Early Modern period in England. While critics have contradictorily seen the devil as a secular figure on the one hand, and as a vestige of sacred drama on the other, I consider the character from an anthropocentric point of view: the devil helps reveal mankind’s emerging independence from religion and the problems that accompany this development. -

Rudimente Von Goethes Faust in Hollywood Am Beispiel Von Neun Filmen

FAUSTISCHE ILLUSION UND REALITÄT: RUDIMENTE VON GOETHES FAUST IN HOLLYWOOD AM BEISPIEL VON NEUN FILMEN By SVEN-OLE ANDERSEN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Sven-Ole Andersen 2 To the most important women in my life: my grandmas Else and Lieselotte, and my mom Heidi 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people have helped me to complete this dissertation. Some have also helped me to endure harsh times while writing it. First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Franz Futterknecht, chair of my supervisory committee. I could not have asked for a better mentor. Besides his literary expertise, I admire especially his analytical abilities and the fact that he did not lose his humor while supporting me during the process of writing the chapters of this dissertation. I would also like to acknowledge not only his abundant help and support but that of the other members of my committee: Dr. Otto Johnston, Dr. Richard Burt, and Dr. Christopher Caes. I have never learned so much about German history and literature than in the courses I took with Dr. Johnston. I owe a great deal to Dr. Caes, and also to Dr. Burt, with whom I took outstanding courses on the nexus of literature and film. Despite their busy professional lives they always took time off to answer my questions. They are my role models concerning professional attitude and publishing. Words are not enough to express my gratitude to my committee members since they have put in many hours to read, reread, and edit my dissertation. -

Invisible Heroes Manuscript 2012

INVISIBLE HEROES 133 Stories You Were Never Told Roy H. Williams Preface Heroes are dangerous things. Bigger than life, highly exaggerated and always positioned in the most favorable light, a hero is a beautiful lie. We have historic heroes, folk heroes and comic book heroes. We have heroes in books and songs and movies and sport. We have heroes of morality, leadership, kindness and excellence. And nothing is so devastating to our sense of wellbeing as a badly fallen hero. Yes, heroes are dangerous to have. The only thing more dangerous is not to have them. Heroes raise the bar we jump and hold high the standards we live by. They are tattoos on our psyche, the embodiment of all we're striving to be. We create our heroes from our hopes and dreams. And then they create us in their own image. This book doesn't profile the famous athletes, entertainers and political leaders whose stories you know by heart, but heroes whose tales were never told, whose exploits drifted like fog into the darkness of obscurity, whose deeds bounced like erasers off the chalkboard of history when the teacher's back was turned. We dedicate these pages to the Invisible Heroes - many of whom were invisible only because of the color of their skin - others, because their fame loomed so large in our minds that we could not see beyond it. America remembers John Steinbeck only as the Nobel Prize-winning novelist of Grapes of Wrath, Cannery Row, East of Eden, and Tortilla Flat. But within these pages you'll find the powerful letter he sent to just one man; a letter far more revealing than any book he ever wrote. -

Titulari Straini Identificati T4 2015

PRODUCATORI STRAINI IDENTIFICATI T4 2015 NR. REP 27/16.05.2016 Difuzari Production Country t Production Year t Title t Producer t Grand Total AFRICA DE SUD 2011 LUNETISTUL: RAZBUNAREA/SNIPER: RELOADED FILM AFRIKA WORLDWIDE 1 1996 RADIO ROMANCE STAR CINEMA PRODUCTIONS 3 ALTELE 2009 ULTIMA LUPTA/MERANTAU PT. MERANTAU FILMS 2 ALTELE Total 5 ARGENTINA-SUA 1994 DESPRE DRAGOSTE SI UMBRE/OF LOVE AND SHADOWS ALEPH PRODUCCIONES S.A. 13 1979 MAD MAX/MAD MAX KENNEDY MILLER ENTERTAINMENT 14 1981 MAD MAX 2: RAZBOINICUL SOSELELOR/MAD MAX 2: THE ROAD WARRIORKENNEDY MILLER ENTERTAINMENT 17 1985 MAD MAX: CUPOLA TUNETULUI/MAD MAX: BEYOND THUNDERDOME KENNEDY MILLER PRODUCTIONS 15 1989 LINISTE APASATOARE/DEAD CALM KENNEDY MILLER PRODUCTIONS 10 1998 MICA SIRENA/THE LITTLE MERMAID WALT DISNEY PICTURES 8 AUSTRALIA 2000 DOMNUL DISTRUGE-TOT/MR. ACCIDENT GOLDWYN FILMS 8 2005 IA-O DE LA CAPAT!/LITTLE FISH PORCHLIGHT FILMS 2 2010 TEROARE IN RED HILL/RED HILL HUGHES HOUSE FILM 5 SINBAD SI MINOTAURUL/SINBAD AND THE MINOTAUR LIMELIGHT INTERNATIONAL MEDIA ENTERTAINMENT 4 2011 TRECUTUL GEORGIEI/SURVIVING GEORGIA MOMO FILMS 15 2011 Total 19 AUSTRALIA Total 98 RIPOSTA UCIGASA (I)/ANSWERED BY FIRE (I) MUSE ENTERTAINMENT ENTERPRISES 3 2006 RIPOSTA UCIGASA (II)/ANSWERED BY FIRE (II) MUSE ENTERTAINMENT ENTERPRISES 3 2006 Total 6 AUSTRALIA-CANADA FRUMOASA SI BESTIA/BEAUTY AND THE BEAST LIMELIGHT INTERNATIONAL MEDIA ENTERTAINMENT 3 2009 MALIBU: RECHINUL ATACA/MALIBU SHARK ATTACK INSIGHT FILM STUDIOS 1 2009 Total 4 2010 FURTUNA DE GHEATA/ARCTIC BLAST F G FILM PRODUCTIONS 6 AUSTRALIA-CANADA Total 16 AUSTRALIA-NOUA ZEELANDA2011 PANICA PE ROCK ISLAND/PANIC AT ROCK ISLAND GOALPOST PICTURES 7 20.000 DE LEGHE SUB MARI II (I)/20.000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA HALLMARK ENTERTAINMENT 1 20.000 DE LEGHE SUB MARI II(II)/20.000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA FREDERICK S.