Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notable Southern Families Vol II

NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II (MISSING PHOTO) Page 1 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II JEFFERSON DAVIS PRESIDENT OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA Page 2 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II Copyright 1922 By ZELLA ARMSTRONG Page 3 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II COMPILED BY ZELLA ARMSTRONG Member of the Tennessee Historical Commission PRICE $4.00 PUBLISHED BY THE LOOKOUT PUBLISHING CO. CHATTANOOGA, TENN. Page 4 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II Table of Contents FOREWORD....................................................................10 BEAN........................................................................11 BOONE.......................................................................19 I GEORGE BOONE...........................................................20 II SARAH BOONE...........................................................20 III SQUIRE BOONE.........................................................20 VI DANIEL BOONE..........................................................21 BORDEN......................................................................23 COAT OF ARMS.............................................................29 BRIAN.......................................................................30 THIRD GENERATION.........................................................31 WILLIAM BRYAN AND MARY BOONE BRYAN.......................................33 WILLIAM BRYAN LINE.......................................................36 FIRST GENERATION -

Historical 50Ciety Montgomery County Pennsylvania J^Onr/Stowjv

BULLETIN HISTORICAL 50CIETY MONTGOMERY COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA J^ONR/STOWJV S2>iery PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY AT IT5 BUILDING )6S*^ DEKALB STREET NORRISTOWN.PA. SPRING, 1969 VOLUME XVI No. 4 PRICE $1.50 The Historical Society of Montgomery County OFFICERS Hon. Alfred L. Taxis, President Robert B. Brunner, Esq., Vice President J. A. Peter Strassburger, Vice President Hon. Robert W. Honeyman, Vice President Howard W. Gross, Treasurer Eva G. Davis, Recording Secretary Mrs. Earl W. Johnson, Corresponding Secretary Mrs. LeRoy Burris, Financial Secretary TRUSTEES Herbert T. Ballard, Jr. Merrill A. Bean Kirke Bryan, Esq. Norris D. Davis Mrs. Andrew Y. Drysdale Donald A. Gallager, Esq. Hon. David E. Groshens Howard W. Gross Kenneth H. Hallman Arthur H. Jenkins Ellwood C. Parry, Jr. Willum S. Pettit John F. Reed Hon. Alfred L. Taxis Mrs. Franklin B. Wildman fir •T '}}• BENJAMIN EASTBURN'S SURVEY IN UPPER MERION TOWN SHIP NOTING AN ERROR IN AN EARLIER SURVEY OF MOUNT JOY MANOR. (See article for interpretive map.) Courtesy Historical Society of Pennsylvania THE BULLETIN of the HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MONTGOMERY COUNTY Published Semi-Annmlly—Spring and Fall Volume XVI Spring, 1969 No. 4 CONTENTS Editorial 259 Traitors by Choice or Chance (concluded) Ellwood C. Parry, Jr. 261 A Palatine Boor, A Short Comprehensive History of the Life of Christopher Sauer I Herbert Harley 286 Benjamin Eastbum John F. Reed 298 The United States Census of 1850, Montgomery County Edited by Jane K. Burris New Hanover Township 313 Whitemarsh Township 383 Reports John F. Beed, Editor PUBLICATION COMMITTEE The Editpr, Chairman Mrs. Leroy Burris William T. -

The Treason Trials of Abraham Carlisle and John Roberts

"A Species of Treason &Not the Least Dangerous Kind": The Treason Trials of Abraham Carlisle and John Roberts N NOVEMBER 4, 1778, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hanged Philadelphia Quakers Abraham Carlisle and John Roberts for collaborating with the enemy during the British occupation of O 1 Philadelphia (November 1777-June 1778). The substantive charges against Carlisle consisted of holding a commission in the king's army and giving intelligence to the British. Roberts faced charges of acting as a guide for the British, encouraging others to enlist in the British cause, and conveying intelligence to the enemy.2 While at first glance the execution of two traitors during wartime may not appear especially noteworthy, the circumstances surrounding the cases of Carlisle and Roberts suggest otherwise. Of the approximately 130 people named under the "Act for the Attainder" who voluntarily surrendered to the authorities of the Commonwealth, only these 1 Pennsylvania Packet, Nov. 5, 1778. Carlisle and Roberts were prosecuted under "An Act for the Attainder of Diverse Traitors," which the Pennsylvania Assembly passed in late 1777 in an attempt to deter people from aiding the British occupation forces. According to the law, persons named in public proclamation had forty-five days to turn themselves over to a justice of the peace. After that time, if captured, the accused faced trial as traitors and, regardless of whether they had been apprehended, suffered the loss of all their property. Proclamations issued by the Supreme Executive Council on May 8,1778, named both Carlisle and Roberts, who turned themselves over to the authorities soon after the patriots returned to Philadelphia. -

13 Pointed Under the Authority of the People Only and Deriving No Power

1776] The S~&u~es& Lar~reof Pennsy1vania~. 13 CHAPTER DCCXXXI. AN ORDINANCE FOR THE APPOINTMENT OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE FOR THE STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA. Whereas it is necessary that proper officers of justice be ap- pointed under the authority of the people only and deriving no power whatever from the late constitution: [Section I.] Be it therefore ordained and declared and it is hereby ordained and declared by the Representatives of the Freemen of the State of Pennsylvania in General Convention met, That David Rittenhouse, Jonathan B. Smith, Owen Biddle, James Cannon, Timothy Matlack, Samuel Morris, the elder, Samuel Howell, Frederick Kuhl, Samuel Morris, the younger, Thomas Wharton, the younger, Henry Kepple, the younger, Joseph Blewer, Samuel Muffin, George Gray, John Bull, Henry Wynkoop, Benjamin Bartholomew, John Hubley, Michael Swoope, William Lyon, Daniel Hunter, Peter Rhoads, Daniel Espy, John Weitzel and John Moore, Esquires, members of the council of safety, are hereby made, constituted and appointed justices of the peace for this state. And that Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, George Bryan, James Young, James Biddle, John Morris, the younger, Joseph Parker, John Bayard, Sharp Delany, John Cadwallader, Joseph Oopperthwaite, Christopher Marshall, the elder, Francis Gur- ney, Robert Knox, Matthew Clarkson, William Coates, William Ball, Philip Boehm, Francis Casper Hasenclever, ThomasOuth- bert, the elder, Moses Bartram, Jacob Schreiner, Joseph Moul- der, Jonathan Paschal, Benjamin Paschal, Benjamin Harbeson, Jacob Bright, Henry Hill, Samuel Ashmead, Frederick Antis, Samuel Erwin, Alexander Edwards, Leth Quee, Samuel Potts, Rowland Evans, Charles Bensel and Peter Evans of the city and county of Philadelphia, Esquires, are hereby made, con- stituted and appointed justices of the peace for the city and county of Philadelphia. -

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository The Supreme Executive Council as an arm of government in Pennsylvania: 1775-1790 Holmes, Burton 1967 Find more at https://preserve.lib.lehigh.edu/ This document is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~· :- ~, ~ j , ,m·\.... , . .I ·' j lliE SUPREME EXEOITIVE COONCIL AS AN ARM OF GOVERNMENT IN PENNSYLVANIA: 1775-1790 By: Burton Holmes .. :.i A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Lehigh University 1967 ' ;,!' • ' ,....•. ·. This Thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of .Master of Arts .,· arge Deparbnent -"!'" \ -'· " .. I I ' ' ·. :' .... ---~··---.. ~-- _. .;.,1:- t·, ,.,,- Table of Contents . ' .+:' I. The Fonnation of The Executive Cowicil. • • • • • • Page 1 II. Presidency of Wharton • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Page 12 I II. Bryan • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Page 24 IV. The Council Under Reed • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Page 33 v. The Council 1n• Peacetime • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Page 73 VI • The Decline of The Council • • • • • • • • • • • • • Page 92 VII. Conclusion • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Page 95 Bibliography. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Page 96 .. ,,_ .. ,· I. The Fonnation of '(he Executive Cotmcil .,, .. On May 10, 1776, John Adams introdu~ed a resolution -

“A Fickle, and Confused Multitude”: War and Politics in Revolutionary

“A Fickle, and Confused Multitude”: War and Politics in Revolutionary Philadelphia, 1750-1783 by Paul Langston B.A., Stephen F. Austin State University, 1997 M.A., University of North Texas, 2006 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 i This thesis entitled: “A Fickle, and Confused Multitude”: War and Politics in Revolutionary Philadelphia, 1750-1783 written by Paul Langston has been approved for the Department of History (Professor Virginia DeJohn Anderson) (Professor Fred W. Anderson) Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Langston, Paul D. (Ph.D., History Department) “A Fickle, and Confused Multitude”: War and Politics in Revolutionary Philadelphia, 1750-1783 Thesis directed by Professor Virginia DeJohn Anderson ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the crucial link between war and politics in Philadelphia during the American Revolution. It demonstrates how war exacerbated existing political conflicts, reshaped prewar political alliances, and allowed for the rise of new political coalitions, all developments that were tied to specific fluctuations in the progress of the military conflict. I argue that the War for Independence played a central role in shaping Philadelphia’s contentious politics with regard to matters of balancing liberty and security. It was amidst this turmoil that the new state government sought to establish its sovereignty and at the same time fend off Pennsylvania’s British enemies. -

Effecting Moral Change: Lessons from the First Emancipation

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 Effecting Moral Change: Lessons from the First Emancipation Howard Landis Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/585 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EFFECTING MORAL CHANGE: LESSONS FROM THE FIRST EMANCIPATION by Howard Landis A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2015 ©2015 Howard Landis All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Professor Jonathan Sassi _____________ ________________________ Date Thesis Advisor Professor Matthew Gold _____________ ________________________ Date Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract EFFECTING MORAL CHANGE: LESSONS FROM THE FIRST EMANCIPATION By Howard Landis Adviser: Professor Jonathan Sassi The First Emancipation was a grassroots movement that resulted in slavery being mostly eliminated in the North by 1830. Without this movement, it is unlikely that slavery would have been banned in the United States by 1865. The First Emancipation is not only a fascinating but little known part of our nation’s history, but can also be used as a case study to illustrate how firmly entrenched, but immoral practices can be changed over time. -

CONTINUE 1 Forms of Payment: Cash Check: CPC Visa Master Card Discover

Print Catalog Order Form Name:_______________________________________________________________________ Company Name: _____________________________________________________________ Address: _____________________________________________________________________ City: _______________________________ State: ____________ Zip:__________________ Phone: _____________________________ Email:__________________________________ Size *Luster Photo Paper Prints *Canvas Gloss Prints & Stretcher Frame Shipping 8X10 $23.95 $74.95 $6.95 11X14 $40.95 $86.95 $6.95 11X17 $47.95 $103.95 $6.95 16X20 $58.95 $109.95 $6.95 20X24 $69.95 $125.95 $6.95 24X30 $81.95 $174.95 $6.95 30X40 $96.95 $232.95 $9.95 *Luster E-Surface Paper (KODAK PROFESSIONAL Portra Endura Paper): Accurate color, realistic saturation, excellent neutral flesh reproduction and brighter colors are just a few of the attributes to describe E-Surface paper. Its 10-mil RC base gives prints a durable photographic feel, and has the highest color gamut available for vivid color reproduction. With this paper don’t worry about prints fading. The standard is 100 years in home display and 200 years in dark storage. *Artist Canvas – Gloss Finish: Poly/Cotton blend. Ideal for photographic & fine art reproductions. Gloss finish for optimum vibrancy, archival quality, and image stability. The canvas print(s) will be mounted on a custom stretcher frame so it will be ready for framing. # Title Format Size Price Qty. Luster Canvas Luster Canvas Luster Canvas Sub-Total $__________________________ S/H Fee (Mail Order Only) $__________________________ Sub-Total $__________________________ 6% PA Sales Tax $__________________________ Grand Total $__________________________ CONTINUE 1 Forms of Payment: Cash Check: CPC Visa Master Card Discover Name on Credit Card:_________________________________________________________ Billing Address: _______________________________________________________________ Credit Card #: ___ ___ ___ ___- ___ ___ ___ __- ___ ___ ___ ___-___ ___ ___ ___ Expiration Date: ___ ___/___ ___ CVV2# (Last 3 Digits above Sig. -

Missouri Historical Review

VOL. IV. JULY, 1910. NO. 4. MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW. PUBLISHED BY THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI F. A. SAMPSON, Secretary, EDITOR. SUBSCRIPTION PRICE $1.00 PER YEAR ISSUED QUARTERLY. COLUMBIA, MO. ENTERED AS SECOND CLASS MAIL MATTER AT COLUMBIA, MO„ JULY 16, 1907 1 ' <!*' MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW. 1 hi EDITOR FRANCIS A. SAMPSON. 1 ' Committee on Publication: '••"'•', '.'.-••• '. :- 4 •'•••& ! JONAS VILES, ISIDOR LOEB, P. A. SAMPSON. j VOL. IV. JULY, 1910. NO. 4 •:; 1| CONTENTS A i Bryant's Station and Its Founder, William Bryant, by Thomas Julian Bryant - 219 Mormon Troubles in Missouri, by Herman C. Smith - ,./ ';;.;. - 238 History of the County Press, by Miss Minnie Organ .... 252 i The Santa Fe Trail, by Prof. G. C. Broadhead 309 '•-•*• i Missouri Weather in Early Days, by Prof. G. i C. Broadhead - - - 320 i Missouri Documents for the Small Public Li brary, by Grace Lefler - - 321 Destruction of Missouri Books — ' - 328 Notes - - - - - 329 Book Notices - - . ' - - 330 Necrology - * - - 330 • i\ ' '" "• ' : ; ' J - r • MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW, VOJU 4. JULY, 1910. NO. 4. BRYANT'S STATION AND ITS FOUNDER, WILLIAM BRYANT. The following article is really but a continuation of one apon the same subject, which appeared in the October (1908) number of the Missouri Historical Review In order to fully substantiate what is therein stated, and to forever make cer tain the name of Bryant's Station, and its founder, William Bryant, this additional article has been prepared. Authorities will be duly cited as to each material statement made, and I be- lieve taat the facts herein set forth, will be found to be unim peachable. -

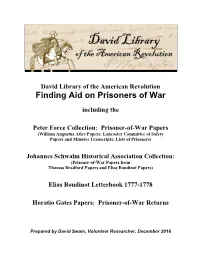

Finding Aid on Prisoners of War

David Library of the American Revolution Finding Aid on Prisoners of War including the Peter Force Collection: Prisoner-of-War Papers (William Augustus Atlee Papers; Lancaster Committee of Safety Papers and Minutes Transcripts; Lists of Prisoners) Johannes Schwalm Historical Association Collection: (Prisoner-of-War Papers from Thomas Bradford Papers and Elias Boudinot Papers) Elias Boudinot Letterbook 1777-1778 Horatio Gates Papers: Prisoner-of-War Returns Prepared by David Swain, Volunteer Researcher, December 2016 Table of Contents Manuscript Sources—Prisoner-of-War Papers 1 Peter Force Collection (Library of Congress) 1 Johannes Schwalm Historical Association Collection (Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Library of Congress) 2 Elias Boudinot Letterbook (State Historical Society 3 of Wisconsin) Horatio Gates Papers (New York Historical Society) 4 General Index 5 Introduction 13 Overview 13 Untangling the Categories of Manuscripts from their 15 Interrelated Sources People Involved in Prisoner-of-War Matters 18 Key People 19 Elias Boudinot 20 Thomas Bradford 24 William Augustus Atlee 28 Friendships and Relationships 31 American Prisoner-of-War Network and System 32 Lancaster Committee of Safety Papers and Minutes 33 Prisoner-of-War Lists 34 References 37 Annotated Lists of Contents: 41 Selected Prisoner-of-War Documents William Augustus Atlee Papers 1758-1791 41 (Peter Force Collection, Series 9, Library of Congress) LancasterCommittee of safety Papers 1775-1777 97 (Peter Force Collection, Series 9, Library of Congress) -

Revolutionary American Jury: a Case Study of the 1778-1779 Philadelphia Treason Trials, The

SMU Law Review Volume 61 Issue 4 Article 4 2008 Revolutionary American Jury: A Case Study of the 1778-1779 Philadelphia Treason Trials, The Carlton F. W. Larson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Carlton F. W. Larson, Revolutionary American Jury: A Case Study of the 1778-1779 Philadelphia Treason Trials, The, 61 SMU L. REV. 1441 (2008) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol61/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE REVOLUTIONARY AMERICAN JURY: A CASE STUDY OF THE 1778-1779 PHILADELPHIA TREASON TRIALS Carlton F.W. Larson* ABSTRACT Between September 1778 and April 1779, twenty-three men were tried in Philadelphiafor high treason against the state of Pennsylvania. These tri- als were aggressively prosecuted by the state in an atmosphere of wide- spread popular hostility to opponents of the American Revolution. Philadelphiajuries, however, convicted only four of these men, a low con- viction rate even in an age of widespread jury lenity; moreover, in three of these four cases, the juries petitioned Pennsylvania'sexecutive authority for clemency. Since it is unlikely that most of the defendants were factually innocent, these low conviction rates must be explained by other factors. This Article offers such an explanation, and, in the process, uses these trials as a case study of jury service in late eighteenth-century America. -

PDF Generated by "Newgen R@Jesh"

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, Fri Jul 19 2019, NEWGEN i The Trials of Allegiance 9780190932749_Book.indb 1 /17_revised_proof/revises_ii/files_to_typesetting/validation 19-Jul-19 10:06:22 PM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, Fri Jul 19 2019, NEWGEN iii The Trials of Allegiance Treason, Juries, and the American Revolution z CARLTON F.W. LARSON 1 9780190932749_Book.indb 3 /17_revised_proof/revises_ii/files_to_typesetting/validation 19-Jul-19 10:06:22 PM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, Fri Jul 19 2019, NEWGEN 1 Introduction When dawn broke on the morning of October 4, 1779, in the fifth year of the American War for Independence, James Wilson of Philadelphia was not expecting to face combat. If he had stood on ceremony, he could have called himself Colonel Wilson (he was formally a colonel in the Cumberland County militia), but his countrymen would probably have rolled their eyes. A scholarly, bespectacled lawyer with no obvious martial abilities, Wilson had yet to draw his sword in battle (Figure I.1). But he had contributed notably to the cause of American independence with an even more powerful weapon— his pen. After emigrating from his native Scotland in his twenties, Wilson had become a leader of the Pennsylvania bar and the author of an influential pamphlet advocating the cause of the American colonies.1 Elected as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, Wilson had proudly signed the Declaration of Independence at the Pennsylvania State House, the building that future generations would enshrine as Independence Hall. Wilson’s conduct had thus made him one of the most prominent American traitors to Great Britain and a rich prize for any British military unit that man- aged to capture him.