A CHURCH BUILT on CHARITY: AUGUSTINE's ECCLESIOLOGY By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4.5 Mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System

4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System. Technique Guide Table of Contents Introduction 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plates 2 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate System 4 AO Principles 5 Indications 6 Surgical Technique Preparation 7 Reduce Articular Surface 11 Insert Plate 12 Insert Screw in Central Plate Head Hole 20 Option A: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screw 20 Option B: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screw 23 Insert Screws in Surrounding Plate Head Holes 26 Option A: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screws 26 Option B: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screws 30 Insert Screws in Plate Shaft 32 Option A: 4.5 mm Cortex Screws 32 Option B: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screws 34 Option C: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screws 37 Remove Instruments 40 Product Information Implants 41 Instruments 43 Set Lists 45 Image intensifier control 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate Technique Guide Synthes 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plates. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System. The Synthes 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate is part of the VA-LCP Periarticular Plating System which merges variable angle locking screw technology with conventional plating techniques. The 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate System has many similarities to standard locking fixation methods, with a few important improvements. Variable angle locking screws provide the ability to create a fixed-angle construct while also allowing the surgeon the freedom to choose the screw trajectory before “fixing” the angle of the screw. -

Technical Specifications & Standard Equipment List

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS & STANDARD EQUIPMENT LIST TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS & STANDARD EQUIPMENT LIST Aircraft Overview The Viking 400S Twin Otter (“400S”) is an all-metal, high wing monoplane, powered by two wing-mounted turboprop engines, The aircraft is delivered with two Pratt and Whitney PT6A-27 driving three-bladed, reversible pitch, fully feathering propellers. engines that incorporate platinum coated CT blades. The aircraft carries a pilot, co-pilot, and up to 17 passengers in standard configuration with a 19 or 15 passenger option. The The 400S will be supplied with new generation composite floats aircraft is a floatplane with no fixed landing gear. that reduce the overall aircraft weight (when compared to Series 400 Twin Otters configured for complex utility or special mission The 400S is an adaptation of the Viking DHC-6 Series 400 Twin operations). The weight savings allows the standard 400S to Otter (“Series 400”). It is specifically designed as an economical carry a 17 passenger load 150 nautical miles with typical seaplane for commercial operations on short to medium reserves, at an average passenger and baggage weight of 191 segments. lbs. (86.5 kg.). The Series 400 is an updated version of the Series 300 Twin Otter. The changes made in developing the Series 400 were 1. General Description selected to take advantage of newer technologies that permit more reliable and economical operations. Aircraft dimensions, Aircraft Dimensions construction techniques, and primary structure have not Overall Height 21 ft. 0 in (6.40 m) changed. Overall Length 51 ft. 9 in (15.77 m) Wing Span 65 ft. 0 in (19.81 m) The aircraft is manufactured at Viking Air Limited facilities in Horizontal Tail Span 20 ft. -

Augustine on Manichaeism and Charisma

Religions 2012, 3, 808–816; doi:10.3390/rel3030808 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article Augustine on Manichaeism and Charisma Peter Iver Kaufman Jepson School, University of Richmond, Room 245, Jepson Hall, 28 Westhampton Way, Richmond, VA 23173, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 5 June 2012; in revised form: 28 July 2012 / Accepted: 1 August 2012 / Published: 3 September 2012 Abstract: Augustine was suspicious of charismatics‘ claims to superior righteousness, which supposedly authorized them to relay truths about creation and redemption. What follows finds the origins of that suspicion in his disenchantment with celebrities on whom Manichees relied, specialists whose impeccable behavior and intellectual virtuosity were taken as signs that they possessed insight into the meaning of Christianity‘s sacred texts. Augustine‘s struggles for self-identity and with his faith‘s intelligibility during the late 370s, 380s, and early 390s led him to prefer that his intermediaries between God and humanity be dead (martyred), rather than alive and charismatic. Keywords: arrogance; Augustine; charisma; esotericism; Faustus; Mani; Manichaeism; truth The Manichaean elite or elect adored publicity. Augustine wrote the first of his caustic treatises against them in 387, soon after he had been baptized in Milan and as he was planning passage back to Africa, where he was born, raised, and educated. Baptism marked his devotion to the emerging mainstream Christian orthodoxy and his disenchantment with the Manichees‘ increasingly marginalized Christian sect, in which, for nine or ten years, in North Africa and Italy, he listened to specialists—charismatic leaders and teachers. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA Doctrina Christiana

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Doctrina Christiana: Christian Learning in Augustine's De doctrina christiana A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Medieval and Byzantine Studies School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Timothy A. Kearns Washington, D.C. 2014 Doctrina Christiana: Christian Learning in Augustine's De doctrina christiana Timothy A. Kearns, Ph.D. Director: Timothy B. Noone, Ph.D. In the twentieth century, Augustinian scholars were unable to agree on what precisely the De doctrina christiana is about as a work. This dissertation is an attempt to answer that question. I have here employed primarily close reading of the text itself but I have also made extensive efforts to detail the intellectual and social context of Augustine’s work, something that has not been done before for this book. Additionally, I have put to use the theory of textuality as developed by Jorge Gracia. My main conclusions are three: 1. Augustine intends to show how all learned disciplines are subordinated to the study of scripture and how that study of scripture is itself ordered to love. 2. But in what way is that study of scripture ordered to love? It is ordered to love because by means of such study exegetes can make progress toward wisdom for themselves and help their audiences do the same. 3. Exegetes grow in wisdom through such study because the scriptures require them to question themselves and their own values and habits and the values and habits of their culture both by means of what the scriptures directly teach and by how readers should (according to Augustine) go about reading them; a person’s questioning of him or herself is moral inquiry, and moral inquiry rightly carried out builds up love of God and neighbor in the inquirer by reforming those habits and values out of line with the teachings of Christ. -

OPUS IMPERFECTUM AUGUSTINE and HIS READERS, 426-435 A.D. by MARK VESSEY on the Fifth Day Before the Kalends of September [In

OPUS IMPERFECTUM AUGUSTINE AND HIS READERS, 426-435 A.D. BY MARK VESSEY On the fifth day before the Kalends of September [in the thirteenth consulship of the emperor 'Theodosius II and the third of Valcntinian III], departed this life the bishop Aurelius Augustinus, most excellent in all things, who at the very end of his days, amid the assaults of besieging Vandals, was replying to I the books of Julian and persevcring glorioi.islyin the defence of Christian grace.' The heroic vision of Augustine's last days was destined to a long life. Projected soon after his death in the C,hronicleof Prosper of Aquitaine, reproduccd in the legendary biographies of the Middle Ages, it has shaped the ultimate or penultimate chapter of more than one modern narrative of the saint's career.' And no wonder. There is something very compelling about the picture of the aged bishop recumbent against the double onslaught of the heretical monster Julian and an advancing Vandal army, the ex- tremity of his plight and writerly perseverance enciphering once more the unfathomable mystery of grace and the disproportion of human and divine enterprises. In the chronicles of the earthly city, the record of an opus mag- num .sed imperfectum;in the numberless annals of eternity, thc perfection of God's work in and through his servant Augustine.... As it turned out, few observers at the time were able to abide by this providential explicit and Prosper, despite his zeal for combining chronicle ' Prosper, Epitomachronicon, a. 430 (ed. Mommsen, MGH, AA 9, 473). Joseph McCabe, .SaintAugustine and His Age(London 1902) 427: "Whilst the Vandals thundered at the walls Augustine was absorbed in his great refutation of the Pelagian bishop of Lclanum, Julian." Other popular biographers prefer the penitential vision of Possidius, hita Augustini31,1-2. -

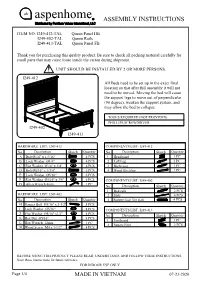

Aspenhome R ASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS

ah aspenhome R ASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS ITEM NO: I249-412-TAL Queen Panel HB I249-402-TAL Queen Rails I249-413-TAL Queen Panel FB Thank you for purchasing this quality product. Be sure to check all packing material carefully for small parts that may come loose inside the carton during shipment. UNIT SHOULD BE INSTALLED BY 2 OR MORE PERSONS. I249-412 All Beds need to be set up in the exact final location so that after full assembly it will not need to be moved. Moving the bed will cause the support legs to move out of perpendicular (90 degree), weaken the support system, and may allow the bed to collapse. TOOLS REQUIRED (NOT PROVIDED) PHILLIPS SCREWDRIVER I249-402 I249-413 HARDWARE LIST: I249-412 COMPONENTS LIST: I249-412 No. Description Sketch Quantity No. Description Sketch Quantity A Bolt Ø1/4" x 1-9/16" 4 PCS 1 Headboard 1 PC B Lock Washer Ø1/4" 4 PCS 2 Left Leg 1 PC C Flat Washer Ø1/4" x 3/4" 4 PCS 3 Right Leg 1 PC D Bolt Ø5/16" x 1-3/4" 6 PCS 4 Wood Stretcher 1 PC E Lock Washer Ø5/16" 6 PCS F Flat Washer Ø5/16" x 3/4" 6 PCS COMPONENTS LIST: I249-402 G Allen Wrench 4mm 1 PC No. Description Sketch Quantity 1 Bed rails 2 PCS HARDWARE LIST: I249-402 2 Slats 4 PCS No. Description Sketch Quantity 3 Support Leg (for slat) 4 PCS H Hanger Bolt Ø5/16" x 3-1/2" 8 PCS I Lock Washer Ø5/16" 8 PCS COMPONENTS LIST: I249-413 J Flat Washer Ø5/16" x1/2" 8 PCS No. -

DEC 3000 Model 400/400S AXP Technical Summary

DEC 3000 Model 400/400S AXP Technical Summary Order Number: EK–SNDPR–TM. B01 Digital Equipment Corporation, Maynard, MA First Printing, November 1992 © Digital Equipment Corporation 1992. All Rights Reserved. No responsibility is assumed for the use or reliability of software on equipment that is not supplied by Digital Equipment Corporation or its affiliated companies. The information in this document is subject to change without notice and should not be construed as a commitment by Digital Equipment Corporation. Digital Equipment Corporation assumes no responsibility for any errors that may appear in this document. The postpaid Reader’s Comments forms at the end of this document request your critical evaluation to assist in preparing future documentation. The following are trademarks of Digital Equipment Corporation: Alpha AXP, AXP, Bookreader, DEC, DECaudio, DECchip 21064, DECconnect, DECnet, DEC OSF/1 AXP, DECwindows, DECwrite, DELNI, DESTA, Digital, OpenVMS AXP, RX26, RZ, ThinWire, TURBOchannel, ULTRIX, VAX, VAXcluster, VAX DOCUMENT, VAXstation, the AXP logo, and the DIGITAL logo. Open Software Foundation is a trademark, and Motif, OSF, OSF/1, and OSF/Motif are registered trademarks of Open Software Foundation, Inc. CD is a trademark of Data General Corporation. Mylar is a registered trademark of E. I. Dupont de Nemours Company, Inc. ISDN is a trademark of Fujitsu Network Switching of America. MIPS is a trademark of MIPS Computer Systems. PostScript is a trademark of Adobe Systems Inc. Prestoserve is a trademark of Legato Systems, Inc.: The trademark and software are licensed to Digital Equipment Corporation by Legato Systems, Inc. FCC NOTICE: This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class A digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. -

Boom Lift Models 400S 460SJ

Operation and Safety Manual Original Instructions - Keep this manual with the machine at all times. Boom Lift Models 400S 460SJ 3121216 ANSI ® May 25, 2012 FOREWORD FOREWORD This manual is a very important tool! Keep it with the machine at all times. The purpose of this manual is to provide owners, users, operators, lessors, and lessees with the precautions and operating procedures essential for the safe and proper machine operation for its intended purpose. Due to continuous product improvements, JLG Industries, Inc. reserves the right to make specification changes without prior notification. Contact JLG Industries, Inc. for updated information. 3121216 – JLG Lift – a FOREWORD SAFETY ALERT SYMBOLS AND SAFETY SIGNAL WORDS This is the Safety Alert Symbol. It is used to alert you to the potential personal injury hazards. Obey all safety messages that follow this symbol to avoid possible injury or death INDICATES AN IMMINENTLY HAZARDOUS SITUATION. IF NOT INDICATES A POTENTIALLY HAZARDOUS SITUATION. IF NOT AVOIDED, WILL RESULT IN SERIOUS INJURY OR DEATH. THIS DECAL AVOIDED, MAY RESULT IN MINOR OR MODERATE INJURY. IT MAY WILL HAVE A RED BACKGROUND. ALSO ALERT AGAINST UNSAFE PRACTICES. THIS DECAL WILL HAVE A YELLOW BACKGROUND. INDICATES A POTENTIALLY HAZARDOUS SITUATION. IF NOT AVOIDED, COULD RESULT IN SERIOUS INJURY OR DEATH. THIS INDICATES INFORMATION OR A COMPANY POLICY THAT RELATES DECAL WILL HAVE AN ORANGE BACKGROUND. DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY TO THE SAFETY OF PERSONNEL OR PRO- TECTION OF PROPERTY. b – JLG Lift – 3121216 FOREWORD For: THIS PRODUCT MUST COMPLY WITH ALL SAFETY RELATED BULLE- • Accident Reporting • Standards and Regulations TINS. CONTACT JLG INDUSTRIES, INC. -

Annual Permit Report for the C-4 Emergency Detention Basin

2013 South Florida Environmental Report Appendix 5-3 Appendix 5-3: Annual Permit Report for the C-4 Emergency Detention Basin Permit Report (May 1, 2011–April 30, 2012) Rick Householder Contributors: Shi Kui Xue, Matt Powers, Christopher King, and John Leslie SUMMARY Based on Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) permit reporting guidelines, Table 1 lists key permit-related information associated with this report. Table 2 lists attachments included with this report. Table A-1 in Attachment A lists the specific pages, tables, graphs, and attachments where project status and annual reporting requirements are addressed. This annual report satisfies the reporting requirements specified in the latest modified permit. Table 1. Key permit-related information. Project Name: C-4 Emergency Detention Basin Permit Numbers: EI 13-0192729-001 and EI 13-0192729-004 Issue and Expiration Dates: EI 13-0192729-001 Issued: 9/10/2002; Expires: 9/9/2007 EI 13-0192729-002 Issued: 2/14/2003 EI 13-0192729-003 Issued: 3/4/2003 EI 13-0192729-004 Issued: 9/26/2003; Expires: 9/25/2008 EI 13-0192729-008 Issued: 2/3/2005 EI 13-0192729-010 Issued: 7/2/2007 EI 13-0192729-011 Issued: 9/25/2008 EI 13-0192729-013 Issued: 2/20/2012 Project Phase: I & II Permit Condition Requiring 20 (in EI 13-0192729-013) Annual Monitoring Report: Relevant Period of Record: May 1, 2011 – April 30, 2012 Rick Householder Report Lead: [email protected] 561-682-6582 John Leslie Permit Coordinator: [email protected] 561-682-6476 App. 5-3-1 Appendix 5-3 Volume III: Annual Permit Reports Table 2. -

The Ruin of the Roman Empire

7888888888889 u o u o u o u THE o u Ruin o u OF THE o u Roman o u o u EMPIRE o u o u o u o u jamesj . o’donnell o u o u o u o u o u o u o hjjjjjjjjjjjk This is Ann’s book contents Preface iv Overture 1 part i s theoderic’s world 1. Rome in 500: Looking Backward 47 2. The World That Might Have Been 107 part ii s justinian’s world 3. Being Justinian 177 4. Opportunities Lost 229 5. Wars Worse Than Civil 247 part iii s gregory’s world 6. Learning to Live Again 303 7. Constantinople Deflated: The Debris of Empire 342 8. The Last Consul 364 Epilogue 385 List of Roman Emperors 395 Notes 397 Further Reading 409 Credits and Permissions 411 Index 413 About the Author Other Books by James J. O’ Donnell Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher preface An American soldier posted in Anbar province during the twilight war over the remains of Saddam’s Mesopotamian kingdom might have been surprised to learn he was defending the westernmost frontiers of the an- cient Persian empire against raiders, smugglers, and worse coming from the eastern reaches of the ancient Roman empire. This painful recycling of history should make him—and us—want to know what unhealable wound, what recurrent pathology, what cause too deep for journalists and politicians to discern draws men and women to their deaths again and again in such a place. The history of Rome, as has often been true in the past, has much to teach us. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0351457 A1 Liu (43) Pub

US 20150351457A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0351457 A1 Liu (43) Pub. Date: Dec. 10, 2015 (54) ELECTRONIC CIGARETTE AND METHOD Publication Classification FOR ADJUSTING FLOW RATE OF GAS FLOW OF ELECTRONIC CGARETTE (51) Int. Cl. A24F 47/00 (2006.01) (71) Applicants:Qiuming Liu, (US); KIMREE (52) U.S. Cl. HI-TECH INC., RoadTown Tortola CPC .................................... A24F 47/008 (2013.01) (VG) (57) ABSTRACT An electronic cigarette comprises a cigarette rod with a bat (72) Inventor: Qiuming Liu, Shenzhen (CN) tery, an atomizer configured to atomize tobacco oil contained therein, and an airflow path configured to enable the air to (21) Appl. No.: 14/759,369 flow into the atomizer. A pressure regulating valve unit arranged in the airflow path includes a floating sphere con (22) PCT Fled: Jan. 3, 2014 figured to close or open the airflow path according to an airflow direction and to adjust the airflow rate flowing into the (86) PCT NO.: PCT/CN2014/0701 12 airflow path. By means of arranging the pressure regulating S371 (c)(1), valve, it is able to control the airflow rate flowing into the (2) Date: Jul. 6, 2015 atomizer, hence adjust the amount of Smoke Sucked to change tastes of smoking and meet users different needs. Moreover, when blowing to the electronic cigarette, the pressure regu (30) Foreign Application Priority Data lating valve unit will be in a closed state to avoid tobacco oil Jan. 5, 2013 (CN) ................. PCT/CN2013/07.0053 inside the atomizer flowing to the battery and a control board. -

Download This PDF File

Athens between East and West: Athenian Elite Self-Presentation and the Durability of Traditional Cult in Late Antiquity Edward Watts T IS GENERALLY ACCEPTED that the urban centers of the Greek-speaking east more quickly dismantled traditional religious infrastructure and disrupted traditional religious I 1 customs than did cities in the west. The city of Athens, how- ever, has always fit awkwardly in this narrative. Alexandria, long Athens’ rival for cultural supremacy in the Greek world, saw its urban infrastructure violently and effectively Christian- ized in the early 390s by the campaigns and construction projects of the bishop Theophilus.2 Alexandria’s civic and political life arguably followed suit after the violence that accompanied the consolidation of episcopal power by Theo- philus’ successor Cyril and the murder of the philosopher Hypatia in the early 410s.3 Antioch and its hinterland saw its pagan institutions disrupted gradually, first through isolated incidents like the conversion (and ultimate destruction) of the 1 See, among others, C. P. Jones, Between Pagan and Christian (Cambridge [Mass.] 2014) 107–143. 2 J. Hahn, “The Conversion of Cult Statues: The Destruction of the Serapeum 392 A.D. and the Transformation of Alexandria into the ‘Christ- Loving’ City,” in J. Hahn et al. (eds.), From Temple to Church: Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity (Leiden 2008) 335–363. Cf. E. Watts, Riot in Alexandria (Berkeley 2010) 191–205. 3 On Hypatia see C. Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity (Baltimore 1997) 295–316; M. Dzielska, Hypatia of Alexandria (Cambridge [Mass.] 1995) 88– 93; E. Watts, Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher (Oxford 2017).