The Art of Caring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Damascus Christos Tsiolkas

AUSTRALIA NOVEMBER 2019 Damascus Christos Tsiolkas The stunningly powerful new novel from the author of The Slap. Description 'They kill us, they crucify us, they throw us to beasts in the arena, they sew our lips together and watch us starve. They bugger children in front of fathers and violate men before the eyes of their wives. The temple priests flay us openly in the streets and the Judeans stone us. We are hunted everywhere and we are hunted by everyone. We are despised, yet we grow. We are tortured and crucified and yet we flourish. We are hated and still we multiply. Why is that? You must wonder, how is it we survive?' Christos Tsiolkas' stunning new novel Damascus is a work of soaring ambition and achievement, of immense power and epic scope, taking as its subject nothing less than events surrounding the birth and establishment of the Christian church. Based around the gospels and letters of St Paul, and focusing on characters one and two generations on from the death of Christ, as well as Paul (Saul) himself, Damascus nevertheless explores the themes that have always obsessed Tsiolkas as a writer: class, religion, masculinity, patriarchy, colonisation, refugees; the ways in which nations, societies, communities, families and individuals are united and divided - it's all here, the contemporary and urgent questions, perennial concerns made vivid and visceral. In Damascus, Tsiolkas has written a masterpiece of imagination and transformation: an historical novel of immense power and an unflinching dissection of doubt and faith, tyranny and revolution, and cruelty and sacrifice. -

Books I've Read Since 2002

Tracy Chevalier – Books I’ve read since 2002 2019 January The Mars Room Rachel Kushner My Sister, the Serial Killer Oyinkan Braithwaite Ma'am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret Craig Brown Liar Ayelet Gundar-Goshen Less Andrew Sean Greer War and Peace Leo Tolstoy (continued) February How to Own the Room Viv Groskop The Doll Factory Elizabeth Macneal The Cut Out Girl Bart van Es The Gifted, the Talented and Me Will Sutcliffe War and Peace Leo Tolstoy (continued) March Late in the Day Tessa Hadley The Cleaner of Chartres Salley Vickers War and Peace Leo Tolstoy (finished!) April Sweet Sorrow David Nicholls The Familiars Stacey Halls Pillars of the Earth Ken Follett May The Mercies Kiran Millwood Hargraves (published Jan 2020) Ghost Wall Sarah Moss Two Girls Down Louisa Luna The Carer Deborah Moggach Holy Disorders Edmund Crispin June Ordinary People Diana Evans The Dutch House Ann Patchett The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Anne Bronte (reread) Miss Garnet's Angel Salley Vickers (reread) Glass Town Isabel Greenberg July American Dirt Jeanine Cummins How to Change Your Mind Michael Pollan A Month in the Country J.L. Carr Venice Jan Morris The White Road Edmund de Waal August Fleishman Is in Trouble Taffy Brodesser-Akner Kindred Octavia Butler Another Fine Mess Tim Moore Three Women Lisa Taddeo Flaubert's Parrot Julian Barnes September The Nickel Boys Colson Whitehead The Testaments Margaret Atwood Mothership Francesca Segal The Secret Commonwealth Philip Pullman October Notes to Self Emilie Pine The Water Cure Sophie Mackintosh Hamnet Maggie O'Farrell The Country Girls Edna O'Brien November Midnight's Children Salman Rushdie (reread) The Wych Elm Tana French On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous Ocean Vuong December Olive, Again Elizabeth Strout* Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead Olga Tokarczuk And Then There Were None Agatha Christie Girl Edna O'Brien My Dark Vanessa Kate Elizabeth Russell *my book of the year. -

The History of British Women's Writing General Editors: Jennie Batchelor

The History of British Women’s Writing General Editors: Jennie Batchelor and Cora Kaplan Advisory Board: Isobel Armstrong, Rachel Bowlby, Helen Carr, Carolyn Dinshaw, Margaret Ezell, Margaret Ferguson, Isobel Grundy, and Felicity Nussbaum The History of British Women’s Writing is an innovative and ambitious monograph series that seeks both to synthesise the work of several generations of feminist schol- ars, and to advance new directions for the study of women’s writing. Volume editors and contributors are leading scholars whose work collectively refl ects the global excellence in this expanding fi eld of study. It is envisaged that this series will be a key resource for specialist and non- specialist scholars and students alike. Titles include: Liz Herbert McAvoy and Diane Watt (editors) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 700– 1500 Volume One Caroline Bicks and Jennifer Summit (editors) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 1500– 1610 Volume Two Mihoko Suzuki (editor) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 1610– 1690 Volume Three Ros Ballaster (editor) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 1690– 1750 Volume Four Jacqueline M. Labbe (editor) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 1750– 1830 Volume Five Mary Joannou (editor) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 1920– 1945 Volume Eight The History of British Women’s Writing Series Standing Order ISBN 978– 0– 230– 20079– 1 hardback (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. Please contact your bookseller or, in case of diffi culty, write to us at the address below with your name and address, the title of the series and the ISBN quoted above. -

Fictive Institutions: Contemporary British Literature and the Arbiters of Value

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository Samantha Purvis Fictive Institutions: Contemporary British Literature and the Arbiters of Value PhD – Literature University of East Anglia Literature, Drama and Creative Writing April 2020 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 1 ABSTRACT My thesis assesses the relationship between contemporary British literature and institutions. Literary culture is currently rife with anxieties that some institutions, such as prizes, exert too much influence over authors, while others, such as literary criticism, are losing their cultural power. As authors are increasingly caught up in complex, ambivalent relationships with institutions, I examine how recent British novels, short stories and ‘creative-critical’ texts thematise these engagements. My thesis mobilises Derrida’s term ‘fictive institution’, which marks the fact that institutions are self-authorising; they are grounded in fictitious or invented origins. Institutions, then, share with literary texts a certain fictionality. My project considers how Rachel Cusk, Olivia Laing, Gordon Burn, Alan Hollinghurst, and— most prominently—Ali Smith, have used the instituting or inventive power of fiction to reflect on the fictionality of institutions. Each chapter assesses how a different institution—academic criticism, public criticism, the book award and publishing— reproduces aesthetic discourses and values which my corpus of literary texts shows to be grounded in an institutional fiction. -

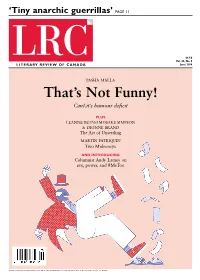

That's Not Funny!

‘Tiny anarchic guerrillas’ PAGE 11 $6.50 Vol. 26, No. 5 June 2018 PASHA MALLA That’s Not Funny! CanLit’s humour deficit PLUS LEANNE BETASAMOSAKE SIMPSON & DIONNE BRAND The Art of Unsettling MARTIN PATRIQUIN Two Mulroneys AND INTRODUCING Columnist Andy Lamey on sex, power, and #MeToo Publications Mail Agreement #40032362. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to LRC, Circulation Dept. PO Box 8, Station K, Toronto, ON M4P 2G1 Literary Review of Canada 100 King Street West, Suite 2575 P.O. Box 35 Station 1st Canadian Place Toronto ON M5X 1A9 email: [email protected] reviewcanada.ca Vol. 26, No. 5 • June 2018 T: 416-861-8227 Charitable number: 848431490RR0001 To donate, visit reviewcanada.ca/support EDITOR IN CHIEF 3 A Little Sincerity 20 Delirious in the Pink House Sarmishta Subramanian Letter from the editor A poem [email protected] Sarmishta Subramanian John Wall Barger ASSISTANT EDITOR Bardia Sinaee 4 The Art of Unsettling 21 Sisterhood of the Secret Pantaloons ASSOCIATE EDITOR Leanne Betasamosake Simpson in Suffragists and their descendants Beth Haddon conversation with Dionne Brand One Hundred Years of Struggle by Joan Sangster POETRY EDITOR and Just Watch Us by Christabelle Sethna and Moira MacDougall 6 Ecclesiasticus XXII Steve Hewitt COPY EDITOR A poem Susan Whitney Patricia Treble George Elliott Clarke CONTRIBUTING EDITORS 23 The Americanization of Oscar Mohamed Huque, Andy Lamey, Molly 8 The Other Side of ‘Irish Eyes’ The early days of a modern celebrity Peacock, Robin Roger, Judy Stoffman Brian Mulroney abroad and at -

Six Minutes Petronella Mcgovern

AUSTRALIA JULY 2019 Six Minutes Petronella McGovern An unputdownable thriller for fans of Liane Moriarty and Caroline Overington. If you were gripped watching The Cry, you'll be hooked on Six Minutes. Description 'Impossible to put down and full of twists and turns you won't see coming! I loved this fabulous debut novel.' Liane Moriarty, bestselling author of Nine Perfect Strangers How can a child disappear from under the care of four playgroup mums? One Thursday morning, Lexie Parker dashes to the shop for biscuits, leaving Bella in the safe care of the other mums in the playgroup. Six minutes later, Bella is gone. Police and media descend on the tiny village of Merrigang on the edge of Canberra. Locals unite to search the dense bushland. But as the investigation continues, relationships start to fracture, online hate messages target Lexie, and the community is engulfed by fear. Is Bella's disappearance connected to the angry protests at Parliament House? What secrets are the parents hiding? And why does a local teacher keep a photo of Bella in his lounge room? What happened in those six minutes and where is Bella? The clock is ticking... This gripping novel will keep you guessing to the very last twist. Price: $29.99 $32.99 ISBN: 9781760875282 About the Author Format: Paperback - C format Petronella McGovern is a writer and editor who grew up on a farm outside Bathurst, NSW. After working in Canberra for a Dimensions: 234x153mm number of years, she now lives on Sydney's northern beaches with her husband and two children. -

The Voices of Surf-Writing / Taj: a Man Above the Reef

The voices of surf-writing / Taj: A man above the reef Author Sandtner, Jake Steven Published 2019-04 Thesis Type Thesis (Masters) School School of Hum, Lang & Soc Sc DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/783 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/385905 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au The voices of surf-writing / Taj: A man above the reef Jake Sandtner, BA, GCertCtve&ProfWriting School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science Arts Education and Law Group Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus Project/Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) April 2019 1 Synopsis The exegesis, ‘The voices of surf-writing’, examines: the relationship between reader and writer in the surf-writing genre; how this relationship is conveyed through voice; and, ultimately, how the delivery methods of surf-journalism, surf-nonfiction and surf-fiction influence the social perception of surf culture in the mass market. Acknowledging that surf-writing is mainly aimed at surfers and those who ‘belong to surf’, the exegesis focusses on the ways surf is delivered in texts, and examines whether the writing is authentic in its themes, tones and voice, while also calling for innovation. The exegesis accompanies a creative work, Taj: A man above the reef, which offers a unique contribution to the future of surf-writing by presenting Taj Burrow’s retirement tale in a new literary format and delivering knowledge earned through industry experience, culture exposure and academic exploration. -

Here in the Anglophone World

MARCH-JULY19_DEF_Layout 1 13/11/18 13:02 Pagina 1 EC EC Introducing EUROPA COMPASS Europa editions March-July 2019 Europa editions www.europaeditions.com Distributed by PGW MARCH-JULY19_DEF_Layout 1 13/11/18 11:43 Pagina 2 INTRODUCING EUROPA COMPASS FROM THE FOUR CORNERS OF THE WORLD, TIMELY NON-FICTION OF ENDURING INTEREST Change brings uncertainty, and with uncertainty comes the need for fresh voices that can open up new perspectives, remind us of the wisdom of the ages, help us clarify and focus our thoughts, or simply distract us from the news cycle for a moment with profound and entertaining books on matters of lasting importance. Europa Compass is a new non-fiction imprint from Europa Editions featuring sophisticated yet accessible titles on travel and contemporary culture, on popular science, history, philosophy, and politics. Books that are informative, entertaining, and diverse. Books by authors who enjoy large readerships and outstanding reputations both in their native countries and in translation but have never been available in English. By translating and publishing these authors, we hope to introduce readers to new points of view, ideas, and narrative styles. Europa Compass also publishes standout works by English-language authors from the U.K., America, Australia, and elsewhere in the Anglophone world. The Europa Compass list is international, diverse, and inclusive. Europa Compass titles are published in a trim size that is slightly smaller than our trademark paperback editions and many titles will be slim volumes that can be read in a handful of sittings and remembered for a lifetime. By 2020, Europa Compass will publish 6 to 8 titles a year. -

Transit a Novel by Rachel Cusk

FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX Reading Group Gold Transit A Novel by Rachel Cusk ISBN: 978-0-374-27862-5 / 272 pages In the wake of her family’s collapse, a writer and her two young sons move to London. The process of this upheaval is the catalyst for a number of transitions—personal, moral, artistic, and practical— as she endeavors to construct a new reality for herself and her children. In the city, she is made to confront aspects of living that she has, until now, avoided, and to consider questions of vulnerability and power, death and renewal, in what becomes her struggle to reattach herself to, and believe in, life. Filtered through the impersonal gaze of its keenly intelligent protagonist, Transit sees Rachel Cusk delve deeper into the themes first raised in her critically acclaimed novel Outline and offers up a penetrating and moving reflection on childhood and fate, the value of suffering, the moral problems of personal responsibility, and the mystery of change. In this second book of a precise, short, yet epic cycle, Cusk describes the most elemental experi- ences, the liminal qualities of life. She captures with unsettling restraint and honesty the longing to both inhabit and flee one’s life, and the wrenching ambivalence animating our desire to feel real. QUESTIONS AND TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION 1. Transit begins with an unnamed narrator describing an online solicitation for an astrological read- ing. What is her attitude toward the e-mail and the astrologer? Is it surprising that she purchases the reading? How does this turn out to be significant later in the book? Contact us at [email protected] | www.ReadingGroupGold.com Don’t forget to check out our monthly newsletter! FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX Reading Group Gold 2. -

Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 5/11/2021 9780374603489 | $28.00 / $38.00 Can

Sorrowland A Novel Rivers Solomon A triumphant, genre-bending breakout novel from one of the boldest new voices in contemporary fiction Vern—seven months pregnant and desperate to escape the strict religious compound where she was raised—flees for the shelter of the woods. There, she gives birth to twins, and plans to raise them far from the influence of the outside world. But even in the forest, Vern is a hunted woman. Forced to fight back against the community that refuses to let her go, she unleashes incredible brutality far beyond what a person should be capable of, her body wracked by inexplicable and uncanny changes. FICTION To understand her metamorphosis and to protect her small family, Vern has MCD | 5/4/2021 to face the past, and more troublingly, the future—outside the woods. Finding 9780374266776 | $27.00 / $36.99 Can. Hardcover with dust jacket | 368 pages the truth will mean uncovering the secrets of the compound she fled but also Carton Qty: 20 | 8.3 in H | 5.4 in W the violent history in America that produced it. 1 Photos 1st, audio, Brit, Trans: FSG Rivers Solomon’s Sorrowland is a genre-bending work of Gothic fiction. dram: Gernert Here, monsters aren’t just individuals, but entire nations. It is a searing, MARKETING seminal book that marks the arrival of a bold, unignorable voice in American fiction. Print features Profiles Rivers Solomon writes about life in the margins, where they are much at home. In AMS addition to appearing on the Stonewall Honor List and winning a Firecracker Award, Targeted social media advertising to fans of Solomon's debut novel An Unkindness of Ghosts was a finalist for a Lambda, a previous books or comp authors Hurston/Wright, an Otherwise (formerly Tiptree) and a Locus award. -

Life Before Carmel Reilly

AUSTRALIA MAY 2019 Life Before Carmel Reilly Suspense and family secrets surround a pair of estranged siblings in a compelling debut thriller. Description She knew she should talk to him. But what was she to say? Once there had been blame to apportion, rage to hurl. Now she no longer had a sense of that. Who knew what the facts of them being here together like this meant. What was she to make of the situation? Scott lying unconscious here in this bed, unknown to her in almost every way. She now a wife, a mother, but in her mind no longer a sister. Not a sister for a very long time now. Lori Spyker is taking her kids to school one unremarkable day when a policeman delivers the news that her brother, Scott Green, has been injured and hospitalised following a hit and run. Lori hasn't seen Scott in decades. She appears to be his only contact. Should she take responsibility for him? Can she? And, if she does, how will she tell her own family about her hidden history, kept secret for so long? Twenty years before, when she and Scott were teenagers, their lives and futures, and those of their family, had been torn to shreds. Now, as Lori tries to piece together her brother's present, she is forced to confront their shared past-and the terrible and devastating truth buried there that had driven them so far apart. Compassionate, wise and shocking, Life Before tells the gripping story of an ordinary family caught in a terrible situation. -

Picador May 2020

PICADOR MAY 2020 PAPERBACK ORIGINAL Groundwork Autobiographical Writings, 1979–2012 Paul Auster An Updated Collection of Nonfiction, including the seminal work The Invention of Solitude, from Man Booker Prize Finalist Paul Auster Paul Auster has spent his fifty-year writing career examining what it means to be truly alive. And now, for the first time ever, in this newly self-curated collection, Auster stitches together various autobiographical writings to lay bare the trajectory of both his personal life and sense of self. BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / LITERARY From his breakout memoir, The Invention of Solitude, which solidified Auster’s Picador | 5/5/2020 9781250245809 | $20.00 / $26.99 Can. reputation as a canonical voice in American letters, to excerpts from his later Trade Paperback | 656 pages | Carton Qty: 20 memoirs, Winter Journal and Report from the Interior, readers are ushered into 8.3 in H | 5.4 in W | 1.2 in T | 1 lb Wt the inner workings of Auster’s self-development. His sweeping recollection Includes 3 black-and-white photographs winds through the halls of Columbia University during the turbulent 1960s and throughout into life as a young poet-turned-novelist, then dives headfirst into the realities Other Available Formats: that accompany aging today. Along the way, Auster continually challenges the Ebook ISBN: 9781250245816 notion of what autobiography can be, inverting the form through fragmentation and, ultimately, illustrating firsthand the brilliance behind “one of the great writers of our time" (San Francisco Chronicle). MARKETING • Advance Reader Copies • National Print and Online Review PRAISE Coverage • Digital Marketing: Online Advertising and Praise for Paul Auster: Social Media Campaign “Auster has an enormous talent for creating worlds that are both fantastic and • Targeted Outreach to Literary Websites believable.