Volume 3 Issue 1 Fall 2005 Edited by N. Reid & J. Gatrell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

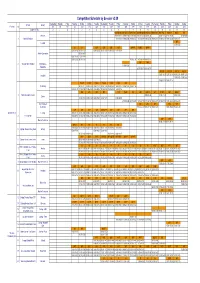

Competition Schedule by Session V2.09

Competition Schedule by Session v2.09 Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday VENUE SPORT Precinct No 6/8 7/8 8/8 9/8 10/8 11/8 12/8 13/8 14/8 15/8 16/8 17/8 18/8 19/8 20/8 21/8 22/8 23/8 24/8 Competition Day -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 M/W/P/QF/SF/FM/W/P/QF/SF/F M/W/P/SF/F M/W/P/QF/SF/FM/W/P/QF/SF/F M/W/P/SF/F M/W/P/SF/F M/W/P/F M/W/F M/F Athletics 09:00-13:25 09:00-13:10 07:30-10:40 09:00-11:58 09:00-11:30 09:00-13:06 07:30-16:00 07:30-10:40 1 National Stadium 19:00-23:20 19:00-22:40 19:00-23:25 19:00-22:10 19:00-22:50 19:00-23:10 19:00-22:18 19:00-22:20 19:00-21:17 M/F Football 12:00-15:00 M W M/F W/F M/F W/F M/W/F M/W/F M/W/F 12:00-14:12 10:00-11:28 10:00-12:56 10:15-12:19 11:00-13:51 11:15-13:14 Artistic Gymnastics 13:30-14:58 16:00-18:12 17:00-18:28 20:00-22:12 20:00-21:28 18:00-21:00 18:00-20:15 18:00-20:15 W/F M/F 2 National Indoor Stadium Gymnastics - 11:00-13:28 Trampoline 20:15-20:57 20:15-20:57 W/C/SF M/C/SF W/C/F M/C/F 12:00-16:15 12:00-16:15 08:00-12:15 08:00-12:15 Handball 13:30-18:20 13:30-18:20 18:00-22:15 18:00-22:15 P P/SF/F P/SF/F P/SF/F P/SF/F P/SF/F P/SF/F SF/F F Swimming 10:00-11:41 10:00-12:03 10:00-11:43 10:00-11:50 10:00-12:03 10:00-11:34 10:00-11:20 10:00-11:30 18:30-21:30 18:30-21:20 18:30-20:08 18:30-20:42 18:30-21:32 18:30-20:40 18:30-21:16 W/F M/F W/F M/F W/P W/SF W/F M/P M/SF/F W/P W/SF/F M/P M/SF/F 3 National Aquatics Center 10:00-11:40 10:00-11:40 10:00-11:40 Diving 14:30-15:40 -

Sponsor Guide Beijing 2008 Olympic Games

Sponsor Guide Beijing 2008 Olympic Games Marketing Department Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad July 2008 Dear friends, In order to facilitate the operations of sponsoring companies in the lead up to and during the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games, BOCOG Marketing has developed this Sponsor Guide. The Guide is to serve the following purposes: Pre-Games training: The Guide can be part of your hospitality-related training programs to ensure that communication protocols and general policies Games time are clearly understood. Games-time reference: The Guide should be used in conjunction with the Spectator Guide to ensure comprehensive information awareness. With the active participation and full support of sponsoring companies, BOCOG Marketing Program has achieved strong financial guarantee for the organization and operation of the Beijing Olympic Games. I’d like to take this opportunity to express our heartfelt gratitude to all the partners. At the Games time, the entire Marketing staff with the Marketing Headquarters Team, the Olympic Brand Protection Team,the Hospitality Team and Marketing staff at competition and non-competition venues will spare no efforts to deliver services to sponsors, to protect sponsor rights and interests and to help sponsors solve problems when needed. I hope you will find this Guide a valuable tool and wish you all the best and every success in your Games-time operation and hospitality programs. Yuan Bin Director, BOCOG Marketing Contents 1 Games-time Marketing Structure 1.1 Marketing -

Olympia Peking 2008 Uefa Euro 2008 Österreich / Schweiz City of Sport - Düsseldorf 1 Jahr Feier - Fc Schalke 04 Und Gazprom

Das Magazin für den größten Sport-Standort der Welt – Feb./März 2008 – Nr. 1 – EUR 3,00 nrw sports OLYMPIA PEKING 2008 UEFA EURO 2008 ÖSTERREICH / SCHWEIZ CITY OF SPORT - DÜSSELDORF 1 JAHR FEIER - FC SCHALKE 04 UND GAZPROM DFB POKAL WUPPERTALER SV - BAYERN MÜNCHEN VON DÜSSELDORF IN ALLE WELT - VIETENTOURS INHALT 12 22 Inhalt 1 Titel Von Düsseldorf in alle Welt: Reiner Calmund, Petra Vieten, Dieter Nuhr 3 Editorial 38 6 Short Stories 8 Sport-Termine in NRW - Februar bis April 2008 Fußball Bundesliga 12 FC Schalke 04 und GAZPROM - Die 1 Jahr Feier 20 Der Schalker Fan Club Verband wird 30 Sportstadt Düsseldorf Special 22 City of Sport - Düsseldorf 24 LTU Arena - ISS Dome - PHILIPSHALLE 28 Düsseldorf - City of Events 32 Alles ist möglich im BURGWÄCHTER CASTELLO 34 Mal Lust - mal Frust - die Düsseldorfer Vereine Olympia Peking 2008 62 38 Olympische Wunderwelten 42 Zielort: Peking, Zielzeit: 8.August 2008 46 Der Wunsch nach perfekten Spielen 48 Sightseeing und Nightlife in Peking 52 Beijing 2008 - Die kulturelle Vielfalt 54 Von Düsseldorf in alle Welt - Vietentours UEFA EURO 2008 62 Die Stadien der Euro 2008 - Teil 1 - Österreich 66 Der Countdown läuft - Das deutsche Team 2008 70 Deutschlands Gegner Teil 1 - Slaven Bilics karierte Erben 72 Gruppe A mit Zündstoff 74 Kulturstadt Wien 76 DFB Pokal Achtelfi nale - Wuppertaler SV - Bayern München 80 Sympathy for the Soviets 76 82 Vorschau und Impressum 4 | nrw sports 1-2008 SHORTSTORIES SHORTSTORIESseit Jahren einstudierten, schier unglaublichen Torwartparaden G’schichten die Massen. KFC Roque Alberto 17.6. 08 - Noch vor dem Start der Vorbereitung auf die Saison 08/09 ist das Bundesliga-Debüt von Matthäus als Co-Trainer ge- von der Isar platzt. -

Report of the IOC Evaluation Commission for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad in 2008

Report of the IOC Evaluation Commission for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad in 2008 Original version: English © International Olympic Committee Lausanne, Switzerland 3 April 2001 Contents General Introduction 5 Osaka 9 Paris 25 Toronto 43 Beijing 59 Istanbul 77 Conclusion 95 Appendices 97 General Introduction The members of the IOC Evaluation As stated, the Commission has a defined technical Commission (the Commission) for the Games evaluation role but it is impossible to ignore of the XXIX Olympiad in 2008 are pleased to the public debate on political issues such as have been part of a new, two-phase candidature human rights which, in the present context, is procedure adopted by the IOC following the imposed on sport. The Commission will not recommendations made by the IOC 2000 deal with this issue other than to acknowledge Commission and subsequent decisions of the the existence of the debate and its continuation. 110th IOC Session in December 1999. Members of the IOC will have to reach their own conclusions. In this new procedure the Commission visited only those cities which had passed the initial The Commission is grateful for the high quality selection phase during which basic technical of the Candidature Files and the presentations requirements were examined by a team of made during the visits. This has greatly assisted experts. in the preparation of this report. On 28th August 2000, five cities were accepted as As additional background information, the Candidate Cities for 2008 by the IOC Executive Commission has been able to call upon Board. independent research on the five Candidate Cities commissioned by the IOC from: It is the opinion of the Commission that this new procedure is an excellent one – as has already MORI (Market & Opinion Research been stated widely in the many positive reactions International) received. -

Institute Report Institutsbericht

Institute Report Institutsbericht No. 17 October 2009 – September 2010 Institute of East Asian Studies Institut für Ostasienwissenschaften Forsthausweg 47057 Duisburg Tel. 0203 379-4113 www.in-east.de 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Editorial . 5 Editorial Spotlight . 7 Im Blickpunkt 1 Board and Advisory Council . 17 Institutsvorstand und Beirat 2 Staff . 18 Mitarbeiter 3 Research Activities . 22 Forschungsaktivitäten 4 Diploma and Doctoral Theses . 32 Abschlussarbeiten, Dissertationen, Habilitationen 5 Courses Offered . 36 Lehrveranstaltungen 6 Guest Lectures, Colloquia and Symposia . 41 Gastvorträge, Vortragsreihen und Symposien 7 Publications by Institute Members . 48 Publikationen von Institutsmitgliedern 8 Lectures and Media Presentations . .56 Vorträge und Medienpräsentationen 9 Professional Activities . 65 Ehrenamtliche Tätigkeiten 10 Study and Research Visits to East Asia . 68 Studien- und Forschungsaufenthalte in Ostasien 11 Library Report . 69 Bibliotheksbericht 12 Duisburg Working Papers . 70 Duisburger Arbeitspapiere 4 EDITORIAL 5 EDITORIAL EDITORIAL Dear reader, EDITORIAL in 2009/10, the Institute of East Asian Studies (IN-EAST) is still adjusting to its two “benign shocks” of 2009, the successful application to host the German Research Foundation-funded Research Training Group (GK 1613) on “Risk and East Asia”, and the opening of the Confucius Institute Metropolis Ruhr in Duisburg, for which two of our members serve as co-directors. It has been an enormous, but rewarding challenge to get the new programmes going, in addition to our ordinary workload. In the meantime, we have already selected the second cohort of doctoral students for the Research Training Group and run several workshops to set up a truly rich training environment. (Frankly speaking, the undersigned envies the young scholars for this great opportunity to sharpen their skills in disciplinary and regional studies in a condensed way). -

CONSTRUCTION of the NATIONAL STADIUM of BEIJING for the 2008 OLYMPICS XUEFEI REN Michigan State University

ARCHITECTURE AND NATION BUILDING IN THE AGE OF GLOBALIZATION: CONSTRUCTION OF THE NATIONAL STADIUM OF BEIJING FOR THE 2008 OLYMPICS XUEFEI REN Michigan State University ABSTRACT: This study examines the relationship between architecture and nation building in the age of globalization, with an analysis of the debates and controversies about the National Stadium, the main sports venue for the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. The article argues that nationalism, along with the cultural ideology of global consumerism, drives the production of flagship architectural projects in China. The dilemma between nationalism and global consumerism has led state politicians and bureaucrats to opt for a global architectural language to narrate national ambitions. The study reveals the rationale underlying the search for global architecture among political elites in China, as well as its mixed consequences for local cultural discourses and politics. On July 30, 2004, in the Olympic Park in north Beijing, the construction site of the National Stadium was unusually quiet. Huge machines were lying on the ground. Workers had been ordered on a two-month-long vacation. The construction of the National Stadium, which started seven months earlier in December 2003, was suddenly stopped by order of the central government. The direct cause for stopping the construction was a petition submitted to the central government by a group of academicians from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the most distinguished academic establishment in physical sciences and architecture. In the letter, the academicians criticized the stadium design for its “extravagance, huge costs, wasteful use of steel, engineering difficulty and potential safety problems.”1 The central government responded to the petition by ordering a financial review of the project. -

Olympic Games (29Th: 2008: Beijing, China) 2

China Gold China’s Quest for Global Power and Olympic Glory 中国金 路漫漫:从辉煌奥运到世界强国 中国金 Edited by FAN Hong 凡红, Duncan Mackay, and Karen Christensen BERKSHIRE PUBLISHING GROUP Great Barrington, Massachusetts Copyright © 2008 by Berkshire Publishing Group LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information Berkshire Publishing Group LLC 314 Main Street Great Barrington, Massachusetts 01230 www.berkshirepublishing.com Editorial Staff Elizabeth Steffey, Thomas Christensen, Marcy Ross, LU Zhouxiang (Paul) Copy Editors Francesca Forrest and Daniel Spinella Cover Designer Joseph DiStefano Interior Designer Martin Lubin Graphic Design Compositor Brad Walrod/High Text Graphics, Inc. Proofreader Mary Bagg Printed by Eurasia in China Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data China gold: China’s quest for global power and Olympic glory/edited by Fan Hong, Duncan Mackay, and Karen Christensen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-933782-64-5 (alk. paper) 1. Olympic Games (29th: 2008: Beijing, China) 2. Sports — China — History. 3. Olympics — Economic aspects — China — Beijing. I. Hong, Fan. II. Mackay, Duncan. III. Christensen, Karen. GV7222008 .C45 2008 796.48 — dc22 2008017790 Contents Contents Acknowledgments vii Foreword viii Karen Christensen China’s Olympic Dream 中国奥运梦 ix FAN Hong 凡红 -

No 14: the Legacy of the Olympic Games from 1896 - 2016 - a Systematic Review of Academic Publications

Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz Faculty of Social Science, Media and Sport Institute of Sport Science Department of Sporteconomics & Sportsociology Johann-Joachim-Becher-Weg 31 55099 Mainz, Germany Working Paper Series Mainzer Papers on Sport Economics & Management No 14: The Legacy of the Olympic Games from 1896 - 2016 - A Systematic Review of Academic Publications November 2017 ANJA SCHEU (corresponding author) & HOLGER PREUSS Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz Institute of Sport Science Johann-Joachim-Becher-Weg 31 55099 Mainz, Germany Email: [email protected] Executive Summary AIM AND METHOD The purpose of this review is to report the findings of a systematic review of literature on the legacy of Olympic Games from 1896 to 2016. The review focuses on the lega- cies for each Games edition as well as on the measurement of legacies. The search process yielded 863 articles. Exclusion criteria were developed and applied. Finally, the review protocol revealed a total of 204 articles included in the analysis. RESULTS In the first instance, general results are reported to identify trends by Games editions, methods and facets of legacy. The analysis reveals a significant increase of literature dealing with the legacy of Olympic Games, with a majority of non-empirical articles. Consequently, these articles describe the legacies, but the legacy was not measured. Empirical articles mostly draw from qualitative interviews followed by quantitative sur- veys. Legacies describing or evaluating structural changes in terms of urban develop- ment are addressed most often in the literature. The second largest share deals with structural changes in terms of beliefs and behavior. This mainly includes studies ex- amining the effect of the Olympic Games on the image of the nation/city as well as on physical activity. -

Lopu LED Display Intro

L o g o LED Display www.lopu.com.cn www.chinalopu.com L o g o Brief Introduction of LOPU Founded in 1994 and backed up by its controlling shareholder, the 14th Research Institute of CETC, Nanjing Lopu Co., Ltd. is among the earliest and largest suppliers who design, develop and manufacture LED Display and Lighting systems, ITS products and microwave devices in mainland China and became a domestically renowned turnkey contractor of system integration and industrial auto-control systems. Our main business includes: • LED Display System (LDS) • LED Lighting System (LLS) • Intelligent Traffic System (ITS) • Microwave Anechoic Chamber and Materials • System Integration and Industrial auto-control systems As a high-tech enterprise, we have been conferred many high-grade certificates by relevant governmental departments and authorities at home and abroad. At the same time, our company is one of the earliest Chinese members of International Sign Association (ISA), a member of the LED Display Sub-Association of Chinese Optoelectronic Association and one of the first batch members of LED display standards workgroup in China. During the past decade, we have provided products and carried out engineering for many important state-level projects. For instance, we provided LED display systems to the indoor swimming pool in National Olympic Center (for IX Asian Games) in Beijing, the Capital Stadium in Beijing, and Tianjing Olympic Center - a major stadium of 2008 Olympic Games. We are one of the earliest Chinese manufacturers exporting LED displays to foreign markets. Till now, we have exported outdoor and indoor LED display products to the USA, Columbia, Cuba, South Africa, the Central Africa and Tanzania.