Interview with Judge Genevieve Blatt May 17, 1980 the First Question That

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Michael J

Gettysburg College Faculty Books 2014 George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Michael J. Birkner Gettysburg College Charles H. Glatfelter Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books Part of the Cultural History Commons, Oral History Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Birkner, Michael J. and Charles H. Glatfelter. George M. Leader, 1918-2013. Musselman Library, 2014. Second Edition. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books/78 This open access book is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Description George M. Leader (1918-2013), a native of York, Pennsylvania, rose from the anonymous status of chicken farmer's son and Gettysburg College undergraduate to become, first a State Senator, and then the 36th governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. A steadfast liberal in a traditionally conservative state, Leader spent his brief time in the governor's office (1955-1959) fighting uphill battles and blazing courageous trails. He overhauled the state's corrupt patronage system; streamlined and humanized its mental health apparatus; and, when a black family moved into the white enclave of Levittown, took a brave stand in favor of integration. -

Reading, Johnstown, Pittsburgh, Aliquippa

Rem a r k s of S o n n to r {t~ ; b e r t H • Hu mph r e y Penn Sque r e Re ad ing , 'Pa . Octobe r 15, 1964 Sena tor Humphrey . Th a nk you very much . Th a nk you . Th a nk you, my friends . All right . Th a nk yo u . Congr essma n Rh odes , l ad i es a nd gentl e me n, my good young friends, may I suggest th a t you just hold up th 2. t enthusia sm . Congr e ssma n Rhodus, memb e rs of th o Cou nty Committee, the fin e a nd good peopl e of Reading, Pennsylv a nia -- ( App l a us e ) - Sena tor Joseph Cl a rk, who hns boo n her o with you today to s po~ k to you ~ nd my d i s tinguished colloa guo in tho Senate , a nd m ~y I add a n ow member of th e United St a t os Se n a te , if you go to L\J or k on ~JcJ v em b o r 3 r d , Go n o v i o v o 8 l 2 t t • :',J o a r e v o r y ·. ploasod to soo you, Gonevi ov o . ( Ap pla use ) I am pa rticul ~ rly h3ppy to como t o tho District of ono of th o mo s t ,bl o a nd dod icatod mom bors of th o Ho us o of Ropr osonta tiv os . -

Judge Richard Disalle for the Commonwealth Court Historical Society

Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania Reminiscences of The Honorable Richard DiSalle Judge DiSalle was a member of the Commonwealth Court from 1978 to 1980. He was interviewed by the Honorable Jeannine Turgeon of the Dauphin County Court of Common Pleas; she was a law clerk for Judge Genevieve Blatt from 1977 to 1979. The interview was conducted in Pittsburgh on June 11, 2010. 1 JUDGE TURGEON: Okay. This is Jeannine Turgeon, and we are here interviewing Judge Richard DiSalle for the Commonwealth Court Historical Society. Now, when did you – you were appointed to the Court originally? JUDGE DISALLE: Yes. JUDGE TURGEON: And that was back in 1977? JUDGE DISALLE: ‘78. JUDGE TURGEON: ‘78. And how did that happen? Did you get a call some late Sunday night pretending to be governor, or how did that happen? JUDGE DISALLE: Unlike Glenn Mencer, I did not get a call late at night asking me if I wanted to be on the Commonwealth Court. We heard that there were vacancies on the Court. There was a vacancy on the Court because of the death of Judge Kramer. JUDGE TURGEON: And he was from Pittsburgh. Wasn’t Harold Kramer from Pittsburgh? JUDGE DISALLE: Yes. So I talked to my colleagues on the Commons Pleas bench. I was on the Common Pleas Court at the time in Washington County. They said, We think you ought to apply for it. So I put in my application and waited what I thought was an ungodly length of time until I found that I was one of three that -- there were three candidates on the short list and I was one of them. -

Democratic Rally, Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, October 11, 1966

, . • f • ~ NOTES VICE PRES I DENT HUBERT HUMPHREY DEMOCRATIC RALLY PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA OCTOBER 11, 1966 A di sti ngui shed citizen of this state once observed about politics: '1'he people are sensible and wi IIi ng; they ask only that their leaders be the same. To succeed with them, talk sense to them.,, We" Democrats are following Ben Franklin's advice. We followed it in 1964. And we are followin g !! in 1966. -- - - ~Talking sense is what this Democratic campaign in Pen~ania is all abol,!t. And the response to this campaign W. ~ · will take Milton Shapp and Leonard Staisey to Harrisburg. S'"(jf~ I also predict that the people will return Bill Moorhead and Elmer Holland to the United States Congress, and wi II send ~ df{.., H.~ John Woh ~rth and Stephen ArnoldA to join them .• -._!> tV , .• ' ·,t. -2- Now, before we go further, I would like to have just a few moments of silent meditation for the opposition party. Our opposition party has many troubles. Time does not permit me to list them all. One of its troubles is that it doesn't understand us. The Democratic Party is just too modern, too lively, and too active for our opposition to understand. For the old Republican Party, our Democratic Party is a mysterious contraption that usually seems to them to be moving in a thousand directions at once. Imagine how confusing that must be for a party that knows only three positions: standing still, spinning counter clockwise, and moving backward. In this instance, it is what they don't know that hurts them. -

Rweas Staf Ukjversjty Li*Braj«Q ? > L Vx V 4 NOMINATIONS of WALTER H

rweas staf ukjversjty Li*braj«q ? > l Vx V 4 NOMINATIONS OF WALTER H. ANNENBER G, JAC OB D . ^ > • F BEAM, AND JOHN S. D. EISENHOWER Art 7 GOVERNMENT Storage HEARING BE FO RE TH E COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITE D STATES SENATE NINE TY -FIRST CONGRESS FIRS T SESSION ON NOMINATIONS OF WALTER H. ANNENBERG TO BE AMBASSADOR TO GREAT BRITAIN, JACOB D. BEAM TO BE AMBASSADOR TO THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS, AND JOHN S. D. EISENH OWER TO BE AMBASSADOR TO BELGIUM MARCH 7, 1969 co — □ ~ ~ ~ □ Printed for the use of th e Committee on Foreign Relations U.S. GOV ERNMEN T PR IN TI NG OFFIC E 26-861 WA SHING TON : 196 9 * * - < Mr COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS J. W. F U L B R IG H T , Arkansas, Chairman JOHN SP ARKM AN, Alabam a GE O R G E D. A IK E N , Vermont MIKE M ANSF IE LD , Montana K A R L E. M UNDT, South Dakota A L B E R T GORE, Tennessee C LIF FO R D P. CASE , New Jersey F R A N K CH U RCH , Idaho JOHN SH ER MAN CO O PER, Kentu cky STU A R T SY M IN GTON, Missouri JOHN J. WILLIAM S, Delaware TH OM AS J. DODD, Connecticut JA CO B K. JA VI TS , New York CLA IB O R N E PE LL, Rhode Island GALE W. McG EE , Wyoming C ar l Mar cy , Chief of Staff A rthur M. K uhl , Chief Clerk (II) ir.». -

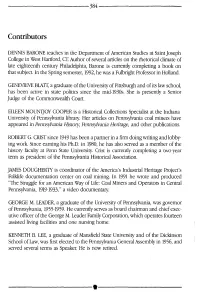

Contributors

384 Contributors DENNIS BARONE teaches in the Department of American Studies at Saint Joseph College in West Hartford, CT Author of several articles on the rhetorical climate of late eighteenth century Philadelphia, Barone is currently completing a book on that subject. In the Spring semester, 1992, he was a Fulbright Professor in Holland. GENEVIEVE BLATT, a graduate of the University of Pittsburgh and of its law school, has been active in state politics since the mid-1930s. She is presently a Senior Judge of the Commonwealth Court. EILEEN MOUNTJOY COOPER is a Historical Collections Specialist at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania library. Her articles on Pennsylvania coal miners have appeared in Pennsylvania Histoiy, Pennsylvania Heritage, and other publications. ROBERT G.CRIST since 1949 has been a partner in a firm doing writing and lobby- ing work. Since earning his Ph.D. in 1980, he has also served as a member of the history faculty at Penn State University. Crist is currently completing a two-year term as president of the Pennsylvania Historical Association. JAMES DOUGHERTY is coordinator of the America's Industrial Heritage Project's Folklife documentation center on coal mining. In 1991 he wrote and produced "The Struggle for an American Way of Life: Coal Miners and Operators in Central Pennsylvania, 1919-1933," a video documentary. GEORGE M. LEADER, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, was governor of Pennsylvania, 1955-1959. He currently serves as board chairman and chief exec- utive officer of the George M.Leader Family Corporation, which operates fourteen assisted living facilities and one nursing home. -

Commentary: Echoes of '64 Campaign in Toomey-Mcginty Race." Philly.Com (October 12, 2016)

History Faculty Publications History 10-12-2016 Commentary: Echoes of '64 Campaign in Toomey- McGinty Race Michael J. Birkner Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac Part of the American Politics Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Birkner, Michael. "Commentary: Echoes of '64 Campaign in Toomey-McGinty Race." Philly.com (October 12, 2016) This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac/77 This open access opinion is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commentary: Echoes of '64 Campaign in Toomey-McGinty Race Abstract With Donald Trump's campaign for president aimed more at solidifying his base rather than reaching out to independents and undecided voters, Republican activists have shifted their focus to holding their Senate majority, which recent polls suggest lie on a knife's edge. The eP nnsylvania U.S. Senate race ranks among the major prizes Democrats hope to capture enroute to the magic number 51. [excerpt] Keywords senate election, pat toomey, katie mcginty, hugh scott, genevieve blatt, pennsylvania politics Disciplines -

Joseph Sill Clark Papers

Collection 1958 Joseph Sill Clark Papers 1947-1968 319 boxes, 224 lin. feet Contact: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107 Phone: (215) 732-6200 FAX: (215) 732-2680 http://www.hsp.org Inventoried by: Katerina Chruma Completed: December 2007 Restrictions: None © 2007 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved Joseph Sill Clark Papers Collection 1958 Joseph Sill Clark Papers, 1947-1968 Collection 1958 319 boxes, 224 linear feet Creator: Clark, Joseph Sill, 1901-1990 Abstract Joseph Sill Clark was a Democratic reform politician from Philadelphia. Early in his career he served as campaign manager for Richardson Dilworth's mayoral campaign, 1947, and as Philadelphia city controller, 1950-1951. He served as mayor of Philadelphia, 1951-1956, and from 1957 to 1968 he was a United States senator from Pennsylvania. This collection is a partial record of Clark career. It consists primarily of material gathered by staff, reports, memoranda, clippings, news releases, articles, with some correspondence, all on issues and events with which Clark was involved. A small portion of the papers are concerned with Clark's early activities as campaign manager for Richardson Dilworth's mayoral campaign, 1947, and as Philadelphia city controller, 1950-1951, for which there are campaign and office files. Clark's records as mayor of Philadelphia, 1951-1956, include campaign papers, some general office files, and transcripts of speeches. The bulk of material covers Clark's years as United States senator from Pennsylvania, 1957-1968. There are papers for his three senatorial campaigns, 1956, 1962, and especially 1968. His Washington office general file reflects his interest in disarmament, the United Nations, Vietnam, and other matters before and after his appointment to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1965. -

Tea at Executive Mansion Association of Boroughs Eugene V

TEA AT EXECUTIVE MANSION ASSOCIATION OF BOROUGHS EUGENE V. ALESSANDRONI, MARY A. DISILVESTRI AND TWO PHOTOGRAPHS WITH GOVERNOR LEADER 1955 SEAL OF SECRETARY OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS PLATE PRESENTED TO MISS BLATT 1956 INTERNAL AFFAIRS OFFICE STATE COMMITTEE DINNER REPRESENTATIVES OF INDONESIA PHILIP CARR'S APPOINTMENT TO SUPERIOR COURT COMMISSION ON THE REORGANIZATION OF STATE GOVERNMENT ADLAI STEVENSON AT AMERICAN LEGION RECOGNITION DINNER FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS AT PITTSBURGH 1956 DEMOCRATIC CONVENTION 1956 DEMOCRATIC FUND RAISING DINNER HELEN HAYS, MARGARET KUHNS, MISS BLATT $100 DINNER, HARRISBURG, HARRY S TRUMAN WINNERS OF 1954 CAMPAIGN 1957 SECRETARY OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS PARDON BOARD'S TRIP TO GRATERFORD PRISON BUTLER SUBURBAN SYMPOSIUM GREETING FRIENDS WHEN DEMOCRATIC CABINET OFFICIALS TOOK OFFICE UNIVERSITY CATHOLIC CLUB DEMOCRATIC WOMEN'S CONFERENCE SECRETARY BLATT RECEIVES KEYS TO WEIGHTS AND MEASURES TEST TRUCK BOARD OF PARDONS AT WESTERN STATE PENN GEOLOGIC SURVEY OPEN HOUSE DEMOCRATIC STATE COMMITTEE DINNER DEPARTMENT OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS PICNIC SWEARING IN CEREMONY AT GOVERNORS OFFICE ANNUAL STEELTON DEMOCRATIC DINNER DEDICATION OF STATE POLICE STATION GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WELL-LOGGING EQUIPMENT PRESIDENT TRUMAN ARRIVES IN HARRISBURG FOR DEMOCRATIC STATE COMMITTEE DINNER DEMOCRATIC STATE COMMITTEE DINNER BRONXVILLE, NY HOTEL, MISS BLATT PERCY FAITH, MISS BLATT AND BOB LENT CANDIDATES LAWRENCE, LEADER, DAVIS, BLATT 22 1958 SECRETARY OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS INTERSTATE OIL COMPACT COMMISSION ELEANOR ROOSEVELT, EMMA MILLER, MISS BLATT, AND GRACE SLOAN PENNSYLVANIA FEDERATION OF DEMOCRATIC WOMEN REVEREND HOWARD JOSEPH CARROLL, BISHOP OF ALTOONA COMMISSION ON CONSTITUTIONAL REVISION NATIONAL JEFFERSON DAY DINNER MISS BLATT AND DR. SAYLOR WITH "CHRIS" AWARD PHILADELPHIA JEFFERSON DAY DINNER BUTLER COUNTY DINNER, JAMES GREEN TOWNSHIP COMMISSIONERS CONVENTION - BUCK HILL FALLS BOROUGHS ASSOCIATION BANQUET 23 1958 WOMEN VOTERS, DEMOCRA'IIC CAMPAIGNING 24 1958 WTPA CHANNEL 27 NEWS, SATURDAY AFTERNOON 25 1958 WOMEN'S DAY 2 6 1958 CHRISTMAS PARTY, DEPT. -

Annual Report 1996

'96 in Brief (listed chronologically) Superior Court president judge James Rowley retires Report of the Administrative Office of North Carolina Pennsylvania Supreme Court Administrative Office of the Courts visits AOPC to 1996 learn about Judicial Computer Project Superior Court judge Donald E. Wieand dies Superior Court is lauded by National Center for State Courts for its expe- ditious efforts in deciding cases despite a heavy caseload Ecuadorean jurists visit Philadelphia Family Court Supreme Court of Pennsylvania to learn American judici- ary’s attitudes on family courts, family violence, Chief Justice John P. Flaherty court administration and Justice Stephen A. Zappala juvenile justice Justice Ralph J. Cappy Justice Ronald D. Castille Justice Russell M. Nigro Justice Sandra Schultz Newman Former Commonwealth Court judge Genevieve Blatt dies. Judge Blatt was the first woman elected to statewide office in Pennsyl-vania and the first woman to serve on the Commonwealth Court Montgomery County senior judge Horace A. Davenport receives the 1996 Golden Crowbar award for initiating the county’s settlement conference program The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania appoints former Supreme Court justice and current Superior Court senior judge Frank J. Montemuro as head of com- mission to study statewide funding of a unified judiciary Chief Justice Robert N.C. Nix, Jr., retires. Chief Justice Nix joined the Supreme Court in 1972 after serving as a Common Pleas Court judge. He became Chief Justice in 1984 Chinese jurists touring the United States to learn about America’s jury system visit Delaware County Courthouse Nancy M. Sobolevitch Court Administrator of Pennsylvania ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE OF PENNSYLVANIA COURTS Members of the international group Philadelphia Office Harrisburg Office The Independent Jury 1515 Market Street - Suite 1414 5035 Ritter Road - Suite 700 spend a week touring Philadel- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102 Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania 17055 phia Courts as guests of the U.S. -

James T. Smith | Partner Business Litigation

James T. Smith | Partner Business Litigation One Logan Square Philadelphia, PA 19103 +1.215.569.5643 [email protected] CO-CHAIR, PHILADELPHIA OFFICE James T. Smith has more than 35 years of experience in complex commercial litigation, products liability, and white collar criminal defense, nationwide. He serves both corporate and individual clients in a wide variety of industries including technology, transportation, healthcare, aerospace, and defense, in disputes involving fraud and abuse, intellectual property, corporate governance, government and internal investigations, white collar criminal defense, and breach of contract and related claims, and many other areas. Jim formerly served for eight years as chair of Blank Rome’s Litigation Department, overseeing more than 250 attorneys across nine practice groups and 13 offices. Prior to that, Jim was the Practice Group Leader for the Commercial Litigation group for six years. Jim served as a law clerk to the Honorable Genevieve Blatt of the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania. For more than a decade, Chambers USA has recognized Jim as a leader in general commercial litigation, noting recently that he is considered to be a “fantastic litigator.” Some of the sources quoted in Chambers said: 2020 James Smith is “a meticulous litigator who knows his business.” 2018 He is able to “strategically think ahead and figure out the best route to that solution better than anyone I have ever met.” 2017 “He is brilliant, super well-prepared and relentless,” reports one impressed source, who also singles out Smith’s “client-oriented” approach. blankrome.com 2016 “He is as smart as can be—the most strategic thinker I’ve met in my life.” Select Engagements Publicly traded cosmetics manufacturer. -

Interparty Competition in Pennsylvania, 1954-68: a Historical and Political Perspective

INTERPARTY COMPETITION IN PENNSYLVANIA, 1954-68: A HISTORICAL AND POLITICAL PERSPECTIVE By ROBERT L. HEALY* HE dynamics of Pennsylvania politics have been examined T from numerous vantage points. A survey of the literature would incorporate historical descriptions of significant state political events,. biographical studies of leading political per- sonalities, 2 journalistic accounts of machine power politics,3 studies of political party organization,4 and treatises concerning the Gen- eral Assembly-its participants, its operation, and its relationship with other governing institutions. 5 One aspect of Pennsylvania politics has held a continuing interest for political scientists-the competition for votes between the two major political parties. Scholarly analysis has usually focused on county voting patterns; these studies had their genesis in the 1940's with the publication of a pamphlet series that researched imterparty county competition from 1922-1944.' These studies and *The author lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. ' See Sylvester K. Stevens, Pennsylvania History in Outline (Harrisburg, 1960). Also, Norman B. Wilkinson, Bibliography of Pennsylvania (Harris- burg, 1957), Pennsylvania Manual, Vol. 97, 63. 2For a summary of state bosses, see E. F. Cooke and G. E. Janosik, Guide To Pennsylvania Politics (New York, 1957), 6-19. Also, Frank Hawkins, "Lawrence of Pittsburgh: Boss of the Mellon Patch," Harper's Magazine, LV (August, 1955). ' Beverly Smith, "How to House Clean a State," Saturday Evening Post, April 14, 1951, 38-39. 'Frank J. Sorauf, Party and Representation (New York, 1963). 'William Keefe, "Parties, Partisanship, and Public Policy in the Penn- sylvania Legislature," American Political Science Review, XLVIII (June, 1954), 452. Kenneth T. Palmer, "The Pennsylvania General Assembly," Pennsylvania Assembly on State Legislatures in American Politics (Pitts- burgh, 1968).