American Literature: a Vanishing Subject?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dickens Fellowship at Komazawa Univ., 8 June, 2002, Ueki

The Dickens Fellowship at Komazawa Univ., 8 June, 2002, Ueki Steven Marcus (b. 1928), George Delacorte Professor in the Humanities, Columbia University * The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, / Earnest Jones, edited and abridged by Lionel Trilling & Steven Marcus. Basic Books, 1961 * Dickens: From Pickwick to Dombey, Chatto & Windus, 1965 * The Other Victorians: A Study of Sexuality and Pornography in Mid-nineteenth Century England, Basic Books, 1966 * "Reading the Illegible", in The Victorian City, 1973 * Engels, Manchester, and the Working Class, Random House, 1974 * Representations: Essays on Literature and Society, Random House, 1975 * Art, Politics, and Will: Essays in Honor of Lionel Trilling, edited by Quintin Anderson, Stephen Donadio, Steven Marcus, Basic Books, 1977 . the committee salutes Marcus' "lifelong commitment to the college, a place where he has worn many hats, including student, administrator and teacher." http://www.columbia.edu/cu/record/archives/vol22/vol22_iss19/record2219.16.html p. 2. Dickens: From Pickwick to Dombey 1. The means Dickens employs, in Pickwick Papers, to achieve the idealization of the relation of father and son is not unfamiliar to us in the literature of a later age: he provides Sam with two fathers, a plenitude in which, like Kipling's Kim but unlike Joyce's Stephen Dedalus, Sam luxuriates. On the one hand there is the actual father, Tony, with whom Sam is altogether intimate and direct, for over him Tony holds only the authority of affection: when he and Sam initially meet in the novel, it is the first time in more than two years that they have seen each other. -

Sacvan Bercovitch Literary Historian and Theorist RSA19 004.Qxd 12-05-2010 17:33 Pagina 80 RSA19 004.Qxd 12-05-2010 17:33 Pagina 81

RSA19_004.qxd 12-05-2010 17:33 Pagina 79 FORUM Sacvan Bercovitch Literary Historian and Theorist RSA19_004.qxd 12-05-2010 17:33 Pagina 80 RSA19_004.qxd 12-05-2010 17:33 Pagina 81 RSA Journal 19/2008 GIUSEPPE NORI Introduction Sacvan Bercovitch, who turned 75 in 2008, retired from the academy at the end of 2001. Harvard celebrated him with a day in his honor, on May 14, 2002, at the elegantly renovated Barker Center, headquarters of the Department of English and American Literature and Language. Many friends, colleagues, and former students convened in Cambridge for the event. An “unforgettable day” (“Retirement” 145), as Saki himself said in a moving thank-you speech at the end of the panels that closed the afternoon session of the conference (The Next Turn in American Literary and Cultural Studies, organ- ized by Werner Sollors and sponsored by The History of American Civilization Program, the English Department, and the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History, Harvard University). Christopher Looby mentioned the conference in his “Tribute to Sacvan Bercovitch, MLA Honored Scholar of Early American Literature,” while I devoted a brief narrative to that “Red- Letter Day” in the Annali of the School of Education of the University of Macerata, trying to recapture the feelings and the mental energies of such an intensely personal and intellectual venue. While critical assessments on the scholarly achievement of Sacvan Bercovitch and tributes to him (critical, institutional, and personal) keep flowing in journal essays and books, newspapers and websites from year to year, awards and recognitions have also piled up after his retirement – “MLA Honored Scholar of Early American Literature” (2002), “Hubbell Award for Lifetime Achievement in American Literary Studies” (2004), “Bode-Pearson Prize for Lifetime Achievement in American Studies” (2007). -

The Moral Imagination: from Edmund Burke to Lionel Trilling'

H-Albion Weaver on Himmelfarb, 'The Moral Imagination: From Edmund Burke to Lionel Trilling' Review published on Sunday, July 1, 2007 Gertrude Himmelfarb. The Moral Imagination: From Edmund Burke to Lionel Trilling. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee Publisher, 2006. xv + 259 pp. $26.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-56663-624-7; $16.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-56663-722-0. Reviewed by Stewart Weaver (Department of History, University of Rochester)Published on H- Albion (July, 2007) Divided Natures In this latest of her several collections of occasional essays, Gertrude Himmelfarb offers subtle appreciations of some notable thinkers and writers who besides being "eminently praiseworthy" in themselves have, she says, enriched her life and been especially important to her own political and philosophical development (p. ix). Though with one exception all of the essays have appeared in print before--some of them more than once, oddly--together they have original interest both for their close juxtaposition and for what they reveal about the evolving interests and attitudes of a prominent American Victorianist. The oldest essay, an "untimely appreciation" of the popular novelist John Buchan, dates to 1960; the most recent, a centenary tribute to Lionel Trilling, dates to 2005. The rest range in origin widely across the intervening forty-five years and they encompass a wide variety of subjects. Not surprisingly, given what we know of Himmelfarb's own post-Trotskyite disposition, many of her characters (Edmund Burke, Benjamin Disraeli, Michael Oakeshott, Winston Churchill) are recognizably conservative. But conservatism is a loose category, especially in the British context, and Himmelfarb is not unduly bound by it. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

Chapter 1 the Traffic in Obscenity

Notes Chapter 1 The traffic in obscenity 1 John Ashcroft, Remarks, Federal Prosecutors’ Symposium on Obscenity, National Advocacy Center, Columbia, SC (6 June 2002); Report from the Joint Select Committee on Lotteries and Indecent Advertisements (London: Vacher & Sons, 1908). 2 Steven Marcus, The Other Victorians: A Study of Sexuality and Pornography in Mid-Nineteenth-Century England (New York: Basic, 1964). 3 The earliest legal term for this print crime in Britain was obscenity, and I therefore prefer it to more recent terminology. 4 Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, 1969, trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith (London: Routledge, 2001). 5 Society for the Suppression of Vice (London: S. Gosnell, 1825), 29. 6 Robert Darnton, The Forbidden Best-Sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France (New York: Norton, 1995); Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge: MIT, 1999); Lisa Gitelman and Geoffrey B. Pingree eds, New Media, 1740–1914 (Cambridge, MA: MIT 2003); and David Thorburn and Henry Jenkins, eds, Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003). 7 Anthony Giddens, Runaway World: How Globalization is Reshaping Our Lives (New York: Routledge, 2002), 1. 8 Jean Baudrillard, The Ecstasy of Communication, ed. Sylvère Lotringer, trans. Bernard and Caroline Schutze (Paris: Editions Galilée, 1988), 22, 24. 9 Laurence O’Toole, Pornocopia: Porn, Sex, Technology and Desire (London: Serpent’s Tale, 1999), 51. 10 Baudrillard, The Ecstasy, 24. 11 Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1979), 87. 12 Saree Makdisi, Romantic Imperialism: Universal Empire and the Culture of Modernity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 128. 13 Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa, 1876–1912, 1991 (London: Abacus, 2001), 140, 122. -

Books Received THOMAS PYLES: Selected Essays on English Usage

books received THOMAS PYLES: Selected Essays on English Usage. By John Algeo. University Presses of Florida. 1979. $18.00. THE ACHIEVEMENT OF MARGARET FULLER. By Margaret Vanderhaar Allen. Pennsylvania State University Press. 1979. $13.50. REBELS AND VICTIMS: The Fiction of Richard Wright and Bernard Malamud. By Evelyn Gross Avery. Kennikat Press. 1979. $10.00. TALES FROM A RESERVATION STOREKEEPER. By Raleigh E. Barker. American Studies Press. 1979. Paper: $2.50. THE PEOPLE'S VOICE: The Orator in American Society. By Baskerville Barnet. The University Press of Kentucky. 1979. $14.50. THE AMERICAN INDIAN IN SHORT FICTION: An Annotated Bibliography. By Peter G. Beidler and Marion F. Egge. Scarecrow Press. 1979. $10.00. AMERICANS ON THE ROAD: From Autocamp to Motel, 1910-1945. By Warren James Belasco. The MIT Press. 1979. $14.95. THE AMERICAN JERMIAD. By Sacvan Bercovitch. University of Wisconsin Press. 1978. $15.00. FROM WILDERNESS TO WASTELAND: The Trial of the Puritan God in the American Imagination. By Charles Berryman. Kennikat Press. 1979. $15.00. BITING OFF THE BRACELET: A Study of Children in Hospitals. By Ann Hill Beuf. University of Pennsylvania Press. 1979. $9.95. NORTHWEST PERSPECTIVES: Essays on the Culture of the Pacific Northwest. Edited by Edwin R. Bingham and Glen A. Love. University of Washington Press. 1979. $14.95. THE FREDERICK DOUGLASS PAPERS: Series One: Speeches, Debates and Inter views. Volume 1: 1841-46. Edited by John W. Blassingame. Yale University Press. 1979. $35.00. ALCOHOL, REFORM AND SOCIETY: The Liquor Issue in Social Context. Edited by Jack S. Blocker, Jr. Greenwood Press. 1979. -

0. Sollorscv2013

CURRICULUM VITAE WERNER SOLLORS Henry B. and Anne M. Cabot Professor of English Literature and Professor of African and African American Studies Harvard University, Barker Center, 12 Quincy Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 phone (617) 495-4113 or -4146; fax (617) 496-2871; e-mail [email protected] web: http://scholar.harvard.edu/wsollors or http://aaas.fas.harvard.edu/faculty/werner_sollors.html Chair, Department of Afro-American Studies, 1984-1987, 1988-1990; Chair, Committee on Higher Degrees in the History of American Civilization, 1997-2002; Director of Undergraduate Studies, Department of English and American Literature and Language, 1997- 2001; Chair, Ethnic Studies, 2001-2004, 2009-2010; Director of Graduate Studies, Department of African and African American Studies, 2005-2007, 2009-2010; Voting faculty member in Comparative Literature Department; Service as Mellon Faculty advisor; on Faculty Council; in Undergraduate Admissions; Graduate Admissions (English, American Civilization, African American Studies, and Comparative Literature); Folklore and Mythology; Core Curriculum Committee; Special Concentrations; Library Digitalization Committee; Summer School Advisory Committee; numerous senior and junior search and promotion committees EDUCATION: Goethe-Gymnasium Frankfurt, Freie Universität Berlin, Wake Forest College, Columbia University DEGREE: Dr. phil.: Freie Universität Berlin, 1975 PAST TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Assistant and Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature, Columbia University Wissenschaftlicher Assistent und Assistenzprofessor, John F. Kennedy-Institut, Freie Universität Berlin Visiting professor at München, Berlin, Bern, Hebrew University Jerusalem, La Sapienza Rome, Università degli Studi di Venezia (chiara fama chair), Nanjing Normal University, and Global Professor of Literature at New York University Global Network University, Abu Dhabi HONORS: Dissertation and Dr. phil., summa cum laude, Berlin 1975; Andrew W. -

Erotic Bonds Among Women in Victorian Literature

571 11 DEBORAH LUTZ Erotic Bonds Among Women in Victorian Literature Anne Lister, an early- nineteenth- century lesbian, wrote in her diary about using Byron’s poetry to seduce – or fl irt with – pretty women. 1 She planned to give the fi fth canto of “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage” (1812) to one young woman, who, when Lister asked her if she liked Byron’s poetry, responded “yes, perhaps too well”; when the girl haunted Lister’s “thoughts like some genius of fairy lore,” she pondered sending her a Cornelian heart with a copy of Byron’s lines on the subject. 2 Women she knew blushed when they “admitted” to having read Don Juan (1819– 1824) and spoke of being “almost afraid” to read Cain (1821). 3 To one of her lovers, Lister read aloud Glenarvon (1816), Lady Caroline Lamb’s melodramatic, fi ctional- ized version of her affair with Byron; they found it a “very dangerous sort of book.” 4 The novel’s heroine cross- dresses, a practice women in Lister’s social circle sometimes used to woo straight women. 5 Lister even played with performing Byronism in her romantic dalliances. 6 Like a bold Byronic hero, she gazed on attractive women with a “penetrating countenance,” and looked “unutterable things” at them, which led them to confess to wishing she “had been a gent.” 7 She tried to “mould” young women “to her purpose,” treating them like toys. 8 But it wasn’t only Byron who pro- vided Lister with ways to act on her own sexual identity. Like many in the nineteenth century who had little access to information about “deviant” types of sexuality, she read classical texts for their descriptions of same- sex desire, especially Juvenal’s Sixth Satire , with its famous lesbian orgy. -

JOHN F. KENNEDY-INSTITUT FÜR NORDAMERIKASTUDIEN Abteilung Für Kultur

JOHN F. KENNEDY-INSTITUT FÜR NORDAMERIKASTUDIEN Abteilung für Kultur WORKING PAPER NO. 36/1991 SACVAN BERCOVITCH Discovering "America": A Cross- Cultural Per:spective Copyright@1991 by Sacvan Bercovitch John F. Kennedy-Institut für Nordamerikastudien Freie Universität Ber1in Lansstrasse 5-9 1000 Ber1in 33 Gerrnany Sacvan Bercovitch Discovering "America": A Cross-Cultural Perspective When 1 first came to the United States, 1 knew virtually nothing about "America." 1 attribute my immigrant naivet~ to the peculiar insularity of my upbringing. 1 was nurtured in the rhetoric of denial. To begin with, 1 absorbed Canada's provincial attitudes toward "The States" -- a provinciality deepened by the pressures of geographical proximity and hardened by the facts of actual dependence. Characteristically, this expressed itself through a mixture of hostility and amnesia, as though we were living next door to an invisible giant, whose invisibility could be interpreted as non-existence. The interpretation was reflected in the virtual absence of "America" throughout my education, from elementary and high school, where U.S. history ended in 1776, to my fortuitous college training at the adult extension of the Montreal YMCA, where a few unavoidable U.S. authors were taught as part of a course on Commonwealth literature. 1 learned certain hard facts, of course, mainly pejorative, and 1 knew the landmarks from Wall Street to Hollywood; but the symbology that connected them--the American dream which elsewhere (1 later discovered) was an open secret, a mystery accredited by the world--remained hidden from ~e, like the spirit in the letter of the uninitiate's text. A more important influence was the Yiddishist-Left Wing world of my parents. -

Modern Europe, 1789-1918 the Age of Revolution and Counterrevolution

SWARTHMORE COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY HISTORY 3A: MODERN EUROPE, 1789-1918 THE AGE OF REVOLUTION AND COUNTERREVOLUTION Spring 2007 Bob Weinberg Office Hours: Monday: 1-3 Trotter 218 Wednesday: 1--3 8133 Thursday: 1--2 rweinbe1 By Appointment This course introduces you to the impact of French Revolution on European politics, society, and culture from the late eighteenth to the early twentieth century. Topics include the revolutionary tradition; industrialization and its social consequences; the emergence of liberalism, feminism, socialism, and conservatism as social and political movements; nationalism and state building; imperialism, the rise of mass society; and world war. I make no attempt to narrate the entire history of the period. Instead, I will focus on a variety of themes and problems in order to illustrate certain key features of European history since 1789. I plan to mix lectures and discussions. It is therefore imperative that you keep up with the assigned readings so you can participate actively in the class All articles and documents are available through Blackboard. In addition, the following books are on reserve in McCabe and available for purchase: Gay Gullickson, Unruly Women of Paris: Images of the Commune Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost Lynn Hunt, Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution Jean-Yves Le Naour, The Living Unknown Soldier: A Story of Grief and the Great War Joan Neuberger and Robin Winks, Europe and the Making of Modernity, 1815-1914 Helmut Walser Smith, The Butcher’s Tale Evgenii Zamiatin, We Course Requirements: Attendance and participation in class discussions Three five-page papers Final Examination Seven-page research paper (Proposal and outline due April 29; Final paper due May 17) Short Papers Due: February 12 March 5 April 2 April 16 Please note that you need to write only three of these papers. -

Dreaming As a Critical Discourse of National Belonging: China Dream, American Dream and World Dream

William A. Callahan Dreaming as a critical discourse of national belonging: China Dream, American Dream and world dream Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Callahan, William A. (2017) Dreaming as a critical discourse of national belonging: China Dream, American Dream and world dream. Nations and Nationalism, 23 (2). pp. 248-270. ISSN 1354- 5078 DOI: 10.1111/nana.12296 © 2017 The Author. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/71009/ Available in LSE Research Online: March 2017 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. 1 William A. Callahan, ‘Dreaming as a Critical Discourse of National Belonging: China Dream, American Dream, and World Dream’, Nations and Nationalism (2017) 23(2):248–270. DOI: 10.1111/nana.12296. -

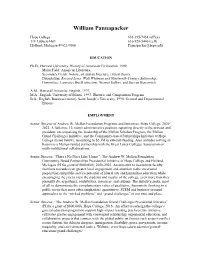

William Pannapacker

William Pannapacker Hope College 616-395-7454 (office) 318 Lubbers Hall 616-928-5440 (cell) Holland, Michigan 49422-9000 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., Harvard University, History of American Civilization, 1999. Major Field: American Literature. Secondary Fields: history, art and architecture, critical theory. Dissertation: Revised Lives: Walt Whitman and Nineteenth-Century Authorship. Committee: Lawrence Buell (director), Werner Sollors, and Sacvan Bercovitch. A.M., Harvard University, English, 1997. M.A., English, University of Miami, 1993. Rhetoric and Composition Program. B.A., English, Business (minor), Saint Joseph’s University, 1990. General and Departmental Honors. EMPLOYMENT Senior Director of Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Programs and Initiatives. Hope College, 2020- 2023. A full-time, 12-month administrative position, reporting directly to the provost and president, encompassing the leadership of the Mellon Scholars Program, the Mellon Grand Challenges Initiative, and the Community-based Partnerships Initiative at Hope College (listed below), amounting to $2.3M in external funding. Also includes serving as liaison to a Mellon-funded partnership with the Great Lakes Colleges Association on multi-institutional collaborations. Senior Director, "There's No Place Like 'Home'": The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Community-Based Partnerships Presidential Initiative of Hope College and Holland, Michigan (PI for grant of $800,000), 2020-2023. An initiative to incentivize faculty members towards even greater local engagement and attention