Unit 18 Regional Cities*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drishti IAS Coaching in Delhi, Online IAS Test Series & Study Material

Drishti IAS Coaching in Delhi, Online IAS Test Series & Study Material drishtiias.com/printpdf/uttar-pradesh-gk-state-pcs-english Uttar Pradesh GK UTTAR PRADESH GK State Uttar Pradesh Capital Lucknow Formation 1 November, 1956 Area 2,40,928 sq. kms. District 75 Administrative Division 18 Population 19,98,12,341 1/20 State Symbol State State Emblem: Bird: A pall Sarus wavy, in Crane chief a (Grus bow–and– Antigone) arrow and in base two fishes 2/20 State State Animal: Tree: Barasingha Ashoka (Rucervus Duvaucelii) State State Flower: Sport: Palash Hockey Uttar Pradesh : General Introduction Reorganisation of State – 1 November, 1956 Name of State – North-West Province (From 1836) – North-West Agra and Oudh Province (From 1877) – United Provinces Agra and Oudh (From 1902) – United Provinces (From 1937) – Uttar Pradesh (From 24 January, 1950) State Capital – Agra (From 1836) – Prayagraj (From 1858) – Lucknow (partial) (From 1921) – Lucknow (completely) (From 1935) Partition of State – 9 November, 2000 [Uttaranchal (currently Uttarakhand) was formed by craving out 13 districts of Uttar Pradesh. Districts of Uttar Pradesh in the National Capital Region (NCR) – 8 (Meerut, Ghaziabad, Gautam Budh Nagar, Bulandshahr, Hapur, Baghpat, Muzaffarnagar, Shamli) Such Chief Ministers of Uttar Pradesh, who got the distinction of being the Prime Minister of India – Chaudhary Charan Singh and Vishwanath Pratap Singh Such Speaker of Uttar Pradesh Legislative Assembly, who also became Chief Minister – Shri Banarsidas and Shripati Mishra Speaker of the 17th Legislative -

Downloaded From

Arakan and Bengal : the rise and decline of the Mrauk U kingdom (Burma) from the fifteenth to the seventeeth century AD Galen, S.E.A. van Citation Galen, S. E. A. van. (2008, March 13). Arakan and Bengal : the rise and decline of the Mrauk U kingdom (Burma) from the fifteenth to the seventeeth century AD. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12637 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12637 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER TWO THE ORIGINS OF THE MRAUK U KINGDOM (1430 – 1593) The sixteenth century saw the rise to power in south-eastern Bengal of the Arakanese kingdom. At the same time the Mughals entered Bengal from the northwest and came into contact with the Arakanese. The arrival of the Mughals and the Arakanese in Bengal would spark a conflict between both parties for control over the economic heart of Bengal situated around Dhaka and Sripur. The war over Bengal would last for approximately ninety years. Starting in the early fifteenth century this Chapter describes the origins of the Mrauk U kingdom and the beginnings of the Ninety Years’ War. 2.1 The early years of the Mrauk U kingdom From the third decade of the fifteenth century the Arakanese kings of Mrauk U extended their hold over the Arakanese littoral. The coastal areas and the major islands Ramree and Cheduba were slowly brought under their control.1 During the sixteenth century successive Arakanese kings were able to gain control over the most important entrepôt of Bengal, Chittagong. -

Monetary Aspects of Bahmani Copper Coinage in Light of the Akola Hoard

Monetary Aspects of Bahmani Copper Coinage in Light of the Akola Hoard Phillip B. Wagoner and Pankaj Tandon Draft: 9/24/16 **Please do not quote or disseminate without permission of the authors** The Bahmanis of the Deccan produced copper coinage from the very outset of the state’s founding in AH 748/1347 CE, but it was clearly secondary to the silver tankas upon which their monetary system was based. By the first several decades of the fifteenth century, however, as John Deyell has shown, the relative production values of silver and copper coinage had reversed, and there was an enormous expansion in copper output, both in terms of the numbers of coins produced and in terms of the range of their denominations (Fig.1).1 This phenomenon has attracted the attention of several scholars, but fundamental questions yet remain about the copper coinage and how it functioned within the Bahmani monetary system. Given the dearth of contemporary written documents shedding light on these matters, it is understandable that many would simply give up on trying to answer these questions. But to do so would be to ignore the physical, material evidence afforded in abundance by the coinage itself, including such aspects as its metrology and denominational structure, and most importantly, the indications of its usage patterns embodied within the composition and geographic distribution of individual coin hoards. Ultimately, we may wish to know why Bahmani copper coinage production should have undergone such a sudden expansion in the 1420s and 1430s, but in order to realize this goal, we must first address the physical nature of the coinage itself and what it can tell us about how it was used. -

The Place of Performance in a Landscape of Conquest: Raja Mansingh's Akhārā in Gwalior

South Asian History and Culture ISSN: 1947-2498 (Print) 1947-2501 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsac20 The place of performance in a landscape of conquest: Raja Mansingh’s akhārā in Gwalior Saarthak Singh To cite this article: Saarthak Singh (2020): The place of performance in a landscape of conquest: Raja Mansingh’s akhārā in Gwalior, South Asian History and Culture, DOI: 10.1080/19472498.2020.1719756 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2020.1719756 Published online: 30 Jan 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 21 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsac20 SOUTH ASIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2020.1719756 The place of performance in a landscape of conquest: Raja Mansingh’s akhārā in Gwalior Saarthak Singh Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, New York, NY, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS In the forested countryside of Gwalior lie the vestiges of a little-known akhārā; landscape; amphitheatre (akhārā) attributed to Raja Mansingh Tomar (r. 1488–1518). performance; performativity; A bastioned rampart encloses the once-vibrant dance arena: a circular stage dhrupad; rāsalīlā in the centre, surrounded by orchestral platforms and an elevated viewing gallery. This purpose-built performance space is a unique monumentalized instance of widely-prevalent courtly gatherings, featuring interpretive dance accompanied by music. What makes it most intriguing is the archi- tectural play between inside|outside, between the performance stage and the wilderness landscape. -

Origin and Development of Urdu Language in the Sub- Continent: Contribution of Early Sufia and Mushaikh

South Asian Studies A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol. 27, No. 1, January-June 2012, pp.141-169 Origin and Development of Urdu Language in the Sub- Continent: Contribution of Early Sufia and Mushaikh Muhammad Sohail University of the Punjab, Lahore ABSTRACT The arrival of the Muslims in the sub-continent of Indo-Pakistan was a remarkable incident of the History of sub-continent. It influenced almost all departments of the social life of the people. The Muslims had a marvelous contribution in their culture and civilization including architecture, painting and calligraphy, book-illustration, music and even dancing. The Hindus had no interest in history and biography and Muslims had always taken interest in life-history, biographical literature and political-history. Therefore they had an excellent contribution in this field also. However their most significant contribution is the bestowal of Urdu language. Although the Muslims came to the sub-continent in three capacities, as traders or business men, as commanders and soldiers or conquerors and as Sufis and masha’ikhs who performed the responsibilities of preaching, but the role of the Sufis and mash‘iskhs in the evolving and development of Urdu is the most significant. The objective of this paper is to briefly review their role in this connection. KEY WORDS: Urdu language, Sufia and Mashaikh, India, Culture and civilization, genres of literature Introduction The Muslim entered in India as conquerors with the conquests of Muhammad Bin Qasim in 94 AH / 712 AD. Their arrival caused revolutionary changes in culture, civilization and mode of life of India. -

Downloaded License

Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 64 (2021) 217-250 brill.com/jesh Regimes of Diplomacy and Law: Bengal-China Encounters in the Early Fifteenth Century Mahmood Kooria Researcher, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands and Visiting faculty, Ashoka University, Sonepat, Haryana, India [email protected] Abstract This article examines the Bengal–China connections between the Ilyās Shāhī and Ming dynasties in the early fifteenth century across the Bay of Bengal and South China Sea. It traces how law played a central role in the cultural geography and diplomatic vocabulary between individuals and communities in foreign lands, with their shared understanding of two nodal points of law. Diplomatic missions explicate how custom- ary, regional and transregional laws were entangled in inter-imperial etiquette. Then there were the religious orders of Islam that constituted an inner circle of imperial exchanges. Between the Ilyās Shāhī rule in Bengal and the Ming Empire in China, certain dimensions of Islamic law provided a common language for the circulation of people and ideas. Stretching between cities and across oceans the interpolity legal exchanges expose interesting aspects of the histories of China and Bengal. Keywords Bengal-China connections – Ming dynasty – Ilyās Shāhī dynasty – interpolity laws – diplomacy – Islam – Indian Ocean Introduction More than a decade ago JESHO published a special issue (49/4), edited by Kenneth R. Hall, on the transregional cultural and economic exchanges and diasporic mobility between South, Southeast and East Asia, an area usually © Mahmood Kooria, 2021 | doi:10.1163/15685209-12341536 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. -

One Odd Day PDF Book

ONE ODD DAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Doris Fisher,Dani Sneed,Karen Lee | 32 pages | 10 Sep 2007 | Arbordale Publishing | 9781934359334 | English | United States One Odd Day PDF Book Extinction Extinction event Holocene extinction Human extinction List of extinction events Genetic erosion Genetic pollution. At the death of 20th Imam Amir, one branch of the Mustaali faith claimed that he had transferred the Imamate to his son At-Tayyib Abu'l-Qasim, who was then two years old. One need not wait for any other Mahdi now. Li Hong. End times Apocalypticism. A hadith from [Ali] adds in this regard, "Mahdi will not appear unless one-third of the people are killed; another one-third die, and the remaining one-third survive. Guess which number of the following sequence is the odd one out. His name will be my name, and his father's name my father's name [9]. Get our free widgets. Since Sunnism has no established doctrine of Mahdi, compositions of Mahdi varies among Sunni scholars. November Learn how and when to remove this template message. But if you see something that doesn't look right, click here to contact us! Word of the Day vindicate. Home Maintenance. The term Mahdi does not occur in the Quran. Within a few years, the collection—including works by Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Marc Chagall —had outgrown the small space. Follow us. Gog and Magog Messianic Age. This article relies too much on references to primary sources. It is argued that one was to be born and rise within the dispensation of Muhammad, who by virtue of his similarity and affinity with Jesus, and the similarity in nature, temperament and disposition of the people of Jesus' time and the people of the time of the promised one the Mahdi is called by the same name. -

MA BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department Of

M.A. BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department of Bengali, Bhasa Bhavana Visva Bharati, Santiniketan Total No- 800 Total Course No- 16 Marks of Per Course- 50 SEMESTER- 1 Objective : To impart knowledge and to enable the understanding of the nuances of the Bengali literature in the social, cultural and political context Outcome: i) Mastery over Bengali Literature in the social, cultural and political context ii) Generate employability Course- I History of Bengali Literature (‘Charyapad’ to Pre-Fort William period) An analysis of the literature in the social, cultural and political context The Background of Bengali Literature: Unit-1 Anthologies of 10-12th century poetry and Joydev: Gathasaptashati, Prakitpoingal, Suvasito Ratnakosh Bengali Literature of 10-15thcentury: Charyapad, Shrikrishnakirtan Literature by Translation: Krittibas, Maladhar Basu Mangalkavya: Biprodas Pipilai Baishnava Literature: Bidyapati, Chandidas Unit-2 Bengali Literature of 16-17th century Literature on Biography: Brindabandas, Lochandas, Jayananda, Krishnadas Kabiraj Baishnava Literature: Gayanadas, Balaramdas, Gobindadas Mangalkabya: Ketakadas, Mukunda Chakraborty, Rupram Chakraborty Ballad: Maymansinghagitika Literature by Translation: Literature of Arakan Court, Kashiram Das [This Unit corresponds with the Syllabus of WBCS Paper I Section B a)b)c) ] Unit-3 Bengali Literature of 18th century Mangalkavya: Ghanaram Chakraborty, Bharatchandra Nath Literature Shakta Poetry: Ramprasad, Kamalakanta Collection of Poetry: Khanadagitchintamani, Padakalpataru, Padamritasamudra -

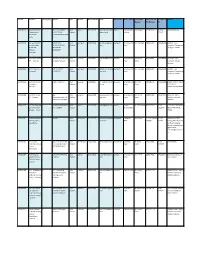

ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Mobile No

ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Mobile No. Of Landline of Address Manager FLC Manager FLC GR09000145 Karpoori Thakur P VILL POST GANDHI Uttar Ballia 9651744234 karpoorithakur1691 Ballia Central Bank N N Kunwar 9415450332 05498- Haldi Kothi,Ballia Dhanushdhari NAGAR TELMA Pradesh @gmail.com of India 225647 Private ITC - JAMALUDDINPUR DISTT Ballia B GR09000192 Sar Sayed School P OHDARIPUR, Uttar Azamgarh 9026699883 govindazm@gmail. Azamgarh Union Bank of Shri R A Singh 9415835509 5462246390 TAMSA F.L.C.C. of Technology RAJAPURSIKRAUR, Pradesh com India Azamgarh, Collectorate, Private ITC - BEENAPARA, Azamgarh, 276001 Binapara - AZAMGARH Azamgarh GR09000314 Sant Kabir Private P Sant Kabir ITI, Salarpur, Uttar Varanasi 7376470615 [email protected] Varanasi Union Bank of Shri Nirmal 9415359661 5422370377 House No: 241G, ITC - Varanasi Rasulgarh,Varanasi Pradesh m India Kumar Ledhupur, Sarnath, Varanasi GR09000426 A.H. Private ITC - P A H ITI SIDHARI Uttar Azamgarh 9919554681 abdulhameeditc@g Azamgarh Union Bank of Shri R A Singh 9415835509 5462246390 TAMSA F.L.C.C. Azamgarh AZAMGARH Pradesh mail.com India Azamgarh, Collectorate, Azamgarh, 276001 GR09001146 Ramnath Munshi P SADAT GHAZIPUR Uttar Ghazipur 9415838111 rmiti2014@rediffm Ghazipur Union Bank of Shri B N R 9415889739 5482226630 UNION BANK OF INDIA Private Itc - Pradesh ail.com India Gupta FLC CENTER Ghazipur DADRIGHAT GHAZIPUR GR09001184 The IETE Private P 248, Uttar Varanasi 9454234449 ietevaranasi@rediff Varanasi Union Bank of Shri Nirmal 9415359661 5422370377 House No: 241G, ITI - Varanasi Maheshpur,Industrial Pradesh mail.com India Kumar Ledhupur, Sarnath, Area Post : Industrial Varanasi GR09001243 Dr. -

Watching, Snorkelling, Whale-Watching

© Lonely Planet Publications 202 Index A Baitul Mukarram Mosque 55 Rocket 66-7, 175, 6 accommodation 157-8 baksheesh 164 to/from Barisal 97-8 activities, see diving, dolphin- Baldha Gardens 54 to/from Chittagong 127-8 watching, snorkelling, Bana Vihara 131 to/from Dhaka 66-8 whale-watching Banchte Shekha Foundation 81 boat trips 158 Adivasis 28, 129, see also individual Bandarban 134-6 Chittagong 125-6 tribes bangla 31 Dhaka 59 Agrabad 125 Bangla, see Bengali Mongla 90 Ahmed, Fakhruddin 24 Bangladesh Freedom Fighters 22 Rangamati 131 Ahmed, Iajuddin 14 Bangladesh Nationalist Party 23 Sariakandi 103 INDEX Ahsan Manzil 52 Bangladesh Tea Research Institute 154 Bogra 101-3, 101 air travel Bangsal Rd 54 books 13, 14, see also literature airfares 170 Bara Katra 53 arts 33 airlines 169-70 Bara Khyang 140 birds 37 to/from Bangladesh 170-2 Barisal 97-9, 98 Chittagong Hill Tracts 28, 29 within Bangladesh 173-5 Barisal division 96-9 culture 26, 27, 28, 31 Ali, Khan Jahan 89 Baro Bazar Mosque 82 emigration 32 Ananda Vihara 145 Baro Kuthi 115 food 40 animals 36, 154-5, see also individual bathrooms 166 history 20, 23 animals Baul people 28 Lajja (Shame) 30 Lowacherra National Park 154-5 bazars, see markets tea 40 Madhupur National Park 77-8 beaches border crossings 172 Sundarbans National Park 93-4, 7 Cox’s Bazar 136 Benapole 82 architecture 31-2, see also historical Himachari Beach 139 Burimari 113 buildings Inani Beach 139 Tamabil 150 area codes 166, see also inside front Benapole 82 Brahmaputra River 35 cover Bengali 190-6 brassware 73 Armenian -

Malda Training Diary

Page 1 of 1 ATI Monograph 13/2006 For restricted circulation only A Probationer’s Training Diary COVER PAGE P. Bhattacharya Learning to Serve Administrative Training Institute Page 2 of 2 Government of West Bengal Page 3 of 3 ATI Monograph 13/2006 For restricted circulation A Probationer’s Training Diary TITLE PAGE P. Bhattacharya Learning to Serve Administrative Training Institute Government of West Bengal Page 4 of 4 Block FC, Bidhannagar (Salt Lake) Kolkata-700106 Page 5 of 5 PREFACE New entrants to the Indian Administrative Service and the West Bengal Civil Service (Executive) have to maintain a Training Diary as part of their district training. While supervising their work in the districts, the ATI faculty has found that in the majority of cases the probationers do not maintain their diaries properly, although these are intended to be records of the details of the training they undergo so that superior officers can check whether they have assimilated the proper lessons from the exposure in the field. During interactions with their Counsellors in the ATI, the trainees have complained that they are handicapped by not having an example to follow. A similar handicap has been reported regarding writing reports of enquiries assigned to probationers in the district. In view of this feedback, the ATI is publishing the diary I maintained in detail as probationer in Malda in 1972, trusting that it will provide civil service probationers with an example of how a training diary can be maintained. We were supposed to send the National Academy of Administration an official training diary and also maintain a personal one. -

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century Thesis submitted for the dc^ee fif DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY By AJAZ BANG Under the supervision of PROF. IQTIDAR ALAM KHAN Department of History Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarb- 1983 T388S 3 0 JAH 1392 ?'0A/ CHE':l!r,D-2002 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY TELEPHONE SS46 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that the thesis entitled 'Soci•-Political Condition Ml VB Wtmmimt of Gujarat / during the fifteenth Century' is an original research work carried out by Aijaz Bano under my Supervision, I permit its submission for the award of the Degree of the Doctor of Philosophy.. /-'/'-ji^'-^- (Proi . Jrqiaao;r: Al«fAXamn Khan) tc ?;- . '^^•^\ Contents Chapters Page No. I Introduction 1-13 II The Population of Gujarat Dxiring the Sixteenth Century 14 - 22 III Gujarat's External Trade 1407-1572 23 - 46 IV The Trading Cotnmxinities and their Role in the Sultanate of Gujarat 47 - 75 V The Zamindars in the Sultanate of Gujarat, 1407-1572 76 - 91 VI Composition of the Nobility Under the Sultans of Gujarat 92 - 111 VII Institutional Featvires of the Gujarati Nobility 112 - 134 VIII Conclusion 135 - 140 IX Appendix 141 - 225 X Bibliography 226 - 238 The abljreviations used in the foot notes are f ollov.'ing;- Ain Ain-i-Akbarl JiFiG Arabic History of Gujarat ARIE Annual Reports of Indian Epigraphy SIAPS Epiqraphia Indica •r'g-acic and Persian Supplement EIM Epigraphia Indo i^oslemica FS Futuh-^ffi^Salatin lESHR The Indian Economy and Social History Review JRAS Journal of Asiatic Society ot Bengal MA Mi'rat-i-Ahmadi MS Mirat~i-Sikandari hlRG Merchants and Rulers in Giijarat MF Microfilm.