Between Greek Nationalism and Ottomanism: Contested Loyalties Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 10, Issue 02, 2021: 28-50 Article Received: 02-02-2021 Accepted: 22-02-2021 Available Online: 28-02-2021 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: https://doi.org/10.18533/jah.v10i2.2053 The Enthroned Virgin and Child with Six Saints from Santo Stefano Castle, Apulia, Italy Dr. Patrice Foutakis1 ABSTRACT A seven-panel work entitled The Monopoli Altarpiece is displayed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts. It is considered to be a Cretan-Venetian creation from the early fifteenth century. This article discusses the accounts of what has been written on this topic, and endeavors to bring field-changing evidence about its stylistic and iconographic aspects, the date, the artists who created it, the place it originally came from, and the person who had the idea of mounting an altarpiece. To do so, a comparative study on Byzantine and early-Renaissance painting is carried out, along with more attention paid to the history of Santo Stefano castle. As a result, it appears that the artist of the central panel comes from the Mystras painting school between 1360 and 1380, the author of the other six panels is Lorenzo Veneziano around 1360, and the altarpiece was not a single commission, but the mounting of panels coming from separate artworks. The officer Frà Domenico d’Alemagna, commander of Santo Stefano castle, had the idea of mounting different paintings into a seven-panel altarpiece between 1390 and 1410. The aim is to shed more light on a piece of art which stands as a witness from the twilight of the Middle Ages and the dawn of Renaissance; as a messenger from the Catholic and Orthodox pictorial traditions and collaboration; finally as a fosterer of the triple Byzantine, Gothic, Renaissance expression. -

Vladimir Paounovsky

THE B ULGARIAN POLICY TTHE BB ULGARIAN PP OLICY ON THE BB ALKAN CCOUNTRIESAND NN ATIONAL MM INORITIES,, 1878-19121878-1912 Vladimir Paounovsky 1.IN THE NAME OF THE NATIONAL IDEAL The period in the history of the Balkan nations known as the “Eastern Crisis of 1875-1879” determined the international political development in the region during the period between the end of 19th century and the end of World War I (1918). That period was both a time of the consolidation of and opposition to Balkan nationalism with the aim of realizing, to a greater or lesser degree, separate national doctrines and ideals. Forced to maneuver in the labyrinth of contradictory interests of the Great Powers on the Balkan Peninsula, the battles among the Balkan countries for superiority of one over the others, led them either to Pyrrhic victories or defeats. This was particularly evident during the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars (The Balkan War and The Interallied War) and World War I, which was ignited by a spark from the Balkans. The San Stefano Peace Treaty of 3 March, 1878 put an end to the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878). According to the treaty, an independent Bulgarian state was to be founded within the ethnographic borders defined during the Istanbul Conference of December 1876; that is, within the framework of the Bulgarian Exarchate. According to the treaty the only loss for Bulgaria was the ceding of North Dobroujda to Romania as compensa- tion for the return of Bessarabia to Russia. The Congress of Berlin (June 1878), however, re-consid- ered the Peace Treaty and replaced it with a new one in which San Stefano Bulgaria was parceled out; its greater part was put under Ottoman control again while Serbia was given the regions around Pirot and Vranya as a compensation for the occupation of Novi Pazar sancak (administrative district) by Austro-Hun- - 331 - VLADIMIR P AOUNOVSKY gary. -

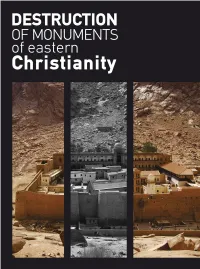

Monuments.Pdf

© 2017 INTERPARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ON ORTHODOXY ISBN 978-960-560 -139 -3 Front cover page photo Sacred Monastery of Mount Sinai, Egypt Back cover page photo Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kiev, Ukrania Cover design Aristotelis Patrikarakos Book artwork Panagiotis Zevgolis, Graphic Designer, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Editing George Parissis, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | International Affairs Directorate Maria Bakali, I.A.O. Secretariat Lily Vardanyan, I.A.O. Secretariat Printing - Bookbinding HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Οι πληροφορίες των κειμένων παρέχονται από τους ίδιους τους διαγωνιζόμενους και όχι από άλλες πηγές The information of texts is provided by contestants themselves and not from other sources ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ Η προστασία της παγκόσμιας πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς, υποδηλώνει την υψηλή ευθύνη της κάθε κρατικής οντότητας προς τον πολιτισμό αλλά και ενδυναμώνει τα χαρακτηριστικά της έννοιας “πολίτης του κόσμου” σε κάθε σύγχρονο άνθρωπο. Η προστασία των θρησκευτικών μνημείων, υποδηλώνει επί πλέον σεβασμό στον Θεό, μετοχή στον ανθρώ - πινο πόνο και ενθάρρυνση της ανθρώπινης χαράς και ελπίδας. Μέσα σε κάθε θρησκευτικό μνημείο, περι - τοιχίζεται η ανθρώπινη οδύνη αιώνων, ο φόβος, η προσευχή και η παράκληση των πονεμένων και αδικημένων της ιστορίας του κόσμου αλλά και ο ύμνος, η ευχαριστία και η δοξολογία προς τον Δημιουργό. Σεβασμός προς το θρησκευτικό μνημείο, υποδηλώνει σεβασμό προς τα συσσωρευμένα από αιώνες αν - θρώπινα συναισθήματα. Βασισμένη σε αυτές τις απλές σκέψεις προχώρησε η Διεθνής Γραμματεία της Διακοινοβουλευτικής Συνέ - λευσης Ορθοδοξίας (Δ.Σ.Ο.) μετά από απόφαση της Γενικής της Συνέλευσης στην προκήρυξη του δεύτερου φωτογραφικού διαγωνισμού, με θέμα: « Καταστροφή των μνημείων της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής ». Επι πλέον, η βούληση της Δ.Σ.Ο., εστιάζεται στην πρόθεσή της να παρουσιάσει στο παγκόσμιο κοινό, τον πολιτισμικό αυτό θησαυρό της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής και να επισημάνει την ανάγκη μεγαλύτερης και ου - σιαστικότερης προστασίας του. -

Ioannis S. Chalkos the 1912 Ottoman Elections and the Greeks in the Vilayet of Adrianople

Ioannis S. Chalkos The 1912 Ottoman elections and the Greeks in the Vilayet of Adrianople: A view from the Greek Archives. The Young Turk governments of the Ottoman Empire (1908-18) are widely considered as a part of the latter’s modernization process.1 The reforms, which had been initiated in the midst of the 19th century, were aiming at the homogenization of the society under the principle of Ottomanism. This was an effort of the Otto- man administrations to attract the loyalty of all their subjects to a new “Ottoman Nation” so as to block the centrifugal tendencies threatening the very existence of the empire.2 However, there was an inherent dualism in this concept of egalitarian- ism promoted through the reforms: the millet system, the old classification of the Ottoman subjects in semi-autonomous religious communities governed by their own law, was preserved and gradually secularized resulting in the stimulation of the separatist nationalist movements.3 Regarding the Greek-Orthodox communi- ties, the Bulgarian ecclesiastical schism of 1870 and the resulting Greco-Bulgarian dispute over Macedonia had strengthened the Greek character of the millet (Rum millet) while the Greek Kingdom was gaining increasing control over its in- stitutions.4 Still the road to an open rift between the Greeks and their Ottoman context was a long one. Developments were shaped and evolved in a changing social and polit- ical landscape which was dominated by continuity rather than specific turning points. The examination of the 1912 Ottoman elections presents an excellent op- portunity for the exploration of this landscape. -

Chameria History - Geographical Space and Albanian Time’

Conference Chameria Issue: International Perspectives and Insights for a Peaceful Resolution Kean University New Jersey USA Saturday, November 12th, 2011 Paper by Professor James Pettifer (Oxford, UK) ‘CHAMERIA HISTORY - GEOGRAPHICAL SPACE AND ALBANIAN TIME’ ‘For more than two centuries, the Ottoman Empire, once so formidable was gradually sinking into a state of decrepitude. Unsuccessful wars, and, in a still greater degree, misgovernment and internal commotions were the causes of its decline.’ - Richard Alfred Davenport,’ The Life of Ali Pasha Tepelena, Vizier of Epirus’i. On the wall in front of us is a map of north-west Greece that was made by a French military geographer, Lapie, and published in Paris in 1821, although it was probably in use in the French navy for some years before that. Lapie was at the forefront of technical innovation in cartography in his time, and had studied in Switzerland, the most advanced country for cartographic science in the late eighteenth century. It is likely that it was made for military use in the Napoleonic period wars against the British. Its very existence is a product of British- French national rivalry in the Adriatic in that period. Modern cartography had many of its roots in the Napoleonic Wars period and immediately before in the Eastern Mediterranean, when intense naval competition between the British and French for control of these waters led to major scientific advances. In turn, in the eighteenth century, similar progress had been made in both countries as a result of earlier wars in the Atlantic. This map is titled ‘Chameria/Thesprotia’, and so at that time it is clear that the two traditional names for the region, Albanian and Greek, were both in common use then, not only locally but by the often classically-educated officers of a European Great Power. -

The Greek Genocide in American Naval War Diaries: Naval Commanders Report and Protest Death Marches and Massacres in Turkey’S Pontus Region, 1921–1922

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 14 Issue 2 Denial Article 14 9-4-2020 Book Review: The Greek Genocide in American Naval War Diaries: Naval Commanders Report and Protest Death Marches and Massacres in Turkey’s Pontus Region, 1921–1922 Thomas Blake Earle Texas A&M University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Earle, Thomas Blake (2020) "Book Review: The Greek Genocide in American Naval War Diaries: Naval Commanders Report and Protest Death Marches and Massacres in Turkey’s Pontus Region, 1921–1922," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 14: Iss. 2: 179-181. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.14.2.1778 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol14/iss2/14 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Review: The Greek Genocide in American Naval War Diaries: Naval Commanders Report and Protest Death Marches and Massacres in Turkey’s Pontus Region, 1921–1922 Thomas Blake Earle Texas A&M University Galveston, Texas, USA The Greek Genocide in American Naval War Diaries: Naval Commanders Report and Protest Death Marches and Massacres in Turkey’s Pontus Region, 1921–1922 Robert Shenk and Sam Koktzoglou, editors New Orleans, University of New Orleans Press, 2020 404 Pages; Price: $24.95 Paperback Reviewed by Thomas Blake Earle Texas A&M University at Galveston Coming on the heels of the more well-known Armenian Genocide, the ethnic cleansing of Ottoman Greeks in the Pontus region of Asia Minor in 1921 and 1922 has received comparatively less attention. -

February Njv Athens Plaza News

P L A Z A N E W S A BUCKET LIST FEBRUARY 2020 FOR YOUR STAY IN ATHENS Q U E A R L O I M T Y D T N I A M E S P I I N T A L T E H V E A N R T S T H E N J V E X P E R I E N C E P L A Z A N E W S 0 1 Relax, enjoy, recharge at The NJV Athens Plaza before & after you head to the city French inspiration G r e e k - F r e n c h C h e f H e n r i G u i b e r t c r e a t e s 2 n e w s p e c i a l m e n u s c o m b i n i n g f a v o r i t e p r o d u c t s o f t h e G r e e k l a n d , f o l l o w i n g a F r e n c h t e c h n i q u e f o r t w o d i f f e r e n t m e n u s t h a t w i l l e n r i c h t h e A t h e n i a n g a s t r o n o m i c e x p e r i e n c e . -

1 Alexander Kitroeff Curriculum Vitae – May 2019 Current Position: Professor, History Department, Haverford College Educa

Alexander Kitroeff Curriculum Vitae – May 2019 History Department, Haverford College, 370 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford PA, 19041 Mobile phone: 610-864-0567 e-mail: [email protected] Current Position: Professor, History Department, Haverford College Education: D.Phil. Modern History, Oxford University 1984 M.A. History, University of Keele 1979 B.A. Politics, University of Warwick 1977 Research Interests: Identity in Greece & its Diaspora from politics to sport Teaching Fields: Nationalism & ethnicity in Modern Europe, Mediterranean, & Modern Greece C19-20th Professional Experience: Professor, Haverford College 2019-present Visiting Professor, College Year in Athens, Spring 2018 Visiting Professor, American College of Greece, 2017-18 Associate Professor, History Dept., Haverford College, 2002-2019 Assistant Professor, History Dept., Haverford College, 1996-2002 Assistant Professor, History Dept. & Onassis Center, New York University, 1990-96 Adjunct Assistant Professor, History Department, Temple University, 1989-90 Visiting Lecturer, History Dept., & Hellenic Studies, Princeton University, Fall 1988 Adj. Asst. Professor, Byz. & Modern Greek Studies, Queens College CUNY, 1986-89 Fellowships & Visiting Positions: Venizelos Chair Modern Greek Studies, The American College in Greece 2011-12 Research Fellow, Center for Byz. & Mod. Greek Studies, Queens College CUNY 2004 Visiting Scholar, Vryonis Center for the Study of Hellenism, Sacramento, Spring 1994 Senior Visiting Member, St Antony’s College, Oxford University, Trinity 1991 Major Research Awards & Grants: Selected as “12 Great Greek Minds at Foreign Universities” by News in Greece 2016 Jaharis Family Foundation, 2013-15 The Stavros S. Niarchos Foundation, 2012 Immigrant Learning Center, 2011 Bank of Piraeus Cultural Foundation, 2008 Proteus Foundation, 2008 Center for Neo-Hellenic Studies, Hellenic Research Institute, 2003 1 President Gerald R. -

1Daskalov R Tchavdar M Ed En

Entangled Histories of the Balkans Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović, University College London Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos, Columbia University Alex Drace-Francis, University of Amsterdam Jasna Dragović-Soso, Goldsmiths, University of London Christian Voss, Humboldt University, Berlin Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic, University of Munich Lenard J. Cohen, Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup, Columbia University Robert M. Hayden, University of Pittsburgh Robert Hodel, Hamburg University Anna Krasteva, New Bulgarian University Galin Tihanov, Queen Mary, University of London Maria Todorova, University of Illinois Andrew Wachtel, Northwestern University VOLUME 9 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Entangled Histories of the Balkans Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover Illustration: Top left: Krste Misirkov (1874–1926), philologist and publicist, founder of Macedo- nian national ideology and the Macedonian standard language. Photographer unknown. Top right: Rigas Feraios (1757–1798), Greek political thinker and revolutionary, ideologist of the Greek Enlightenment. Portrait by Andreas Kriezis (1816–1880), Benaki Museum, Athens. Bottom left: Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864), philologist, ethnographer and linguist, reformer of the Serbian language and founder of Serbo-Croatian. 1865, lithography by Josef Kriehuber. Bottom right: Şemseddin Sami Frashëri (1850–1904), Albanian writer and scholar, ideologist of Albanian and of modern Turkish nationalism, with his wife Emine. Photo around 1900, photo- grapher unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Entangled histories of the Balkans / edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. pages cm — (Balkan studies library ; Volume 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1998 The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity Elena Koumna Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Koumna, Elena, "The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity" (1998). Master's Theses. 3888. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3888 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ORIGINS OF GREEK CYPRIOT NATIONAL IDENTITY by Elena Koumna A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillmentof the requirements forthe Degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1998 Copyrightby Elena Koumna 1998 To all those who never stop seeking more knowledge ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis could have never been written without the support of several people. First, I would like to thank my chair and mentor, Dr. Jim Butterfield, who patiently guided me through this challenging process. Without his initial encouragement and guidance to pursue the arguments examined here, this thesis would not have materialized. He helped me clarify and organize my thoughts at a time when my own determination to examine Greek Cypriot identity was coupled with many obstacles. His continuing support and most enlightening feedbackduring the writing of the thesis allowed me to deal with the emotional and content issues that surfaced repeatedly. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the Unique

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Unique Late Byzantine Image from the Epic of Digenis Akritas: A Study of the Dado Zone in the Church of the Panagia Chrysaphitissa A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Art History by Laura Nicole Horan 2018 © Copyright by Laura Nicole Horan 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Unique Late Byzantine Image from the Epic of Digenis Akritas: A Study of the Dado Zone in the Church of the Panagia Chrysaphitissa by Laura Nicole Horan Master of Arts in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Sharon Elizabeth Gerstel, Chair The epic of Digenis Akritas is one that captivates the audience’s mind as the story of a frontiersman defending the borders of the Byzantine Empire is intertwined with romance and moral virtues. The tale, in both written and oral versions, was spread for centuries throughout the empire. Remnants of the tale exist from mainland Greece, southern Italy and the Peloponnese where this paper is centered. My thesis focuses on a singular depiction of the epic in the church of the Panagia Chrysaphitissa near modern-day Chrysapha, Lakonia: the image of a battle between Digenis Akritas and his foe and lover, Maximou. The presence of a literary figure within the context of a painted church in the rural Morea may at first appear uncomfortable and jarring. How does the ii faithful viewer interpret the intersection of secular folklore imagery and the religious context within an ecclesiastical context. When considered in relationship to the moment in which it was created, the image begins to convey a story of interconnections with the greater world as political unease reshaped the region. -

Dimensions of Transformation in the Ottoman Empire from the Late Medieval Age to Modernity

Dimensions of Transformation in the Ottoman Empire from the Late Medieval Age to Modernity - 9789004442351 Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 02:02:37PM via free access The Ottoman Empire and Its Heritage Politics, Society and Economy Edited by Suraiya Faroqhi Boğaç Ergene Founding Editor Halil İnalcık† Advisory Board Fikret Adanır – Antonis Anastasopoulos – Idris Bostan Palmira Brummett – Amnon Cohen – Jane Hathaway Klaus Kreiser – Hans Georg Majer – Ahmet Yaşar Ocak Abdeljelil Temimi volume 73 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/oeh - 9789004442351 Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 02:02:37PM via free access - 9789004442351 Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 02:02:37PM via free access - 9789004442351 Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 02:02:37PM via free access Dimensions of Transformation in the Ottoman Empire from the Late Medieval Age to Modernity In Memory of Metin Kunt Edited by Seyfi Kenan Selçuk Akşin Somel LEIDEN | BOSTON - 9789004442351 Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 02:02:37PM via free access Cover illustration: “A portion of miniature where Takiyyüddin Râsıd is working, discussing and deliberating along with colleagues in his observatory in the late 16th century Ottoman Empire” (Istanbul University Library, Manuscript, FY, nr. 1404, vr.57a, modified and designed by Lâmia Kenan). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kenan, Seyfi, editor, writer of introduction. | Somel, Selçuk Akşin, editor, writer of introduction. | Kunt, İ. Metin, 1942– honouree. Title: Dimensions of transformation in the Ottoman Empire from the late medieval age to modernity : in memoriam of Metin Kunt / edited by Seyfi Kenan and Selçuk Akşin Somel.