Memorial Statements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Web: the Internet and Section 2257'S Age-Verification and Record-Keeping Requirements, 23 BYU J

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Brigham Young University Law School Brigham Young University Journal of Public Law Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 6 5-1-2008 Ensuring that Only Adults "Go Wild" on the Web: The nI ternet and Section 2257's Age-Verification and Record-keeping Requirements M. Eric Christense Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/jpl Part of the Internet Law Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation M. Eric Christense, Ensuring that Only Adults "Go Wild" on the Web: The Internet and Section 2257's Age-Verification and Record-keeping Requirements, 23 BYU J. Pub. L. 143 (2008). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/jpl/vol23/iss1/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brigham Young University Journal of Public Law by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ensuring that Only Adults ―Go Wild‖ on the Web: The Internet and Section 2257‘s Age-verification and Record-keeping Requirements I. INTRODUCTION Throughout the week, millions of viewers tune in to Comedy Central‘s popular lineup of critically acclaimed programming like The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, The Colbert Report, and South Park.1 During commercial breaks, these viewers are routinely subjected to commercials for the Girls Gone Wild video series.2 The series involves a man traveling around -

Translation of the Eugene Dynkin Interview with Evgenii Mikhailovich Landis

Translation of the Eugene Dynkin Interview with Evgenii Mikhailovich Landis E. B. Dynkin: September 2, 1990. Moscow, Hotel of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. E. B.: Let's begin at the beginning. You entered the university before the war? E. M.: I entered the university before the war, in 1939. I had been there two months when I was recruited into the army---then the army recruited people the way they did up to a year ago. So there I was in the army, and there I stayed till the end of the war. First I was in Finland\footnote{Finnish-Russian war, November 30, 1939-March 12, 1940, essentially a Soviet war of aggression. Hostilities were renewed in June 1941, when Germany invaded the USSR.}, where I was wounded, and for some time after that was on leave. Then I returned to the army, and then the war began\footnote{On June 22, 1941, when Germany invaded the USSR.} and I was in the army for the whole of the war. E. B.: In what branch? E. M.: At first I was in the infantry, and after returning from Finland and recovering from my wound, I ended up in field artillery. E. B.: The probability of surviving the whole of the war as a foot-soldier would have been almost zero. E. M.: I think that this would have been true also in artillery, since this was field artillery, and that is positioned very close to the front. But this is how it was. When the counter-attack before Moscow began in the spring of 1942, our unit captured a German vehicle---a field ambulance, fully fitted out with new equipment, complete with a set of instructions---in German, naturally. -

Journal of the International Palm Society Vol. 58(4) Dec. 2014 the INTERNATIONAL PALM SOCIETY, INC

Palms Journal of the International Palm Society Vol. 58(4) Dec. 2014 THE INTERNATIONAL PALM SOCIETY, INC. The International Palm Society Palms (formerly PRINCIPES) Journal of The International Palm Society Founder: Dent Smith The International Palm Society is a nonprofit corporation An illustrated, peer-reviewed quarterly devoted to engaged in the study of palms. The society is inter- information about palms and published in March, national in scope with worldwide membership, and the June, September and December by The International formation of regional or local chapters affiliated with the Palm Society Inc., 9300 Sandstone St., Austin, TX international society is encouraged. Please address all 78737-1135 USA. inquiries regarding membership or information about Editors: John Dransfield, Herbarium, Royal Botanic the society to The International Palm Society Inc., 9300 Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AE, United Sandstone St., Austin, TX 78737-1135 USA, or by e-mail Kingdom, e-mail [email protected], tel. 44-20- to [email protected], fax 512-607-6468. 8332-5225, Fax 44-20-8332-5278. OFFICERS: Scott Zona, Dept. of Biological Sciences (OE 167), Florida International University, 11200 SW 8 Street, President: Leland Lai, 21480 Colina Drive, Topanga, Miami, Florida 33199 USA, e-mail [email protected], tel. California 90290 USA, e-mail [email protected], 1-305-348-1247, Fax 1-305-348-1986. tel. 1-310-383-2607. Associate Editor: Natalie Uhl, 228 Plant Science, Vice-Presidents: Jeff Brusseau, 1030 Heather Drive, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853 USA, e- Vista, California 92084 USA, e-mail mail [email protected], tel. 1-607-257-0885. -

Calendar of AMS Meetings and Conferences

Calendar of AMS Meetings and Conferences This calendar lists all meetings and conferences approved prior to the date this insofar as is possible. Abstracts should be submitted on special forms which are issue went to press. The summer and annual meetings are joint meetings of the available in many departments of mathematics and from the headquarters office of Mathematical Association of America and the American Mathematical Society. The the Society. Abstracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received meeting dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this is par at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Island, on or before the ticularly true of meetings to which no numbers have been assigned. Programs of deadline given below for the meeting. The abstract deadlines listed below should the meetings will appear in the issues indicated below. First and supplementary be carefully reviewed since an abstract deadline may expire before publication of announcements of the meetings will have appeared in earlier issues. Abstracts a first announcement. Note that the deadline for abstracts for consideration for of papers presented at a meeting of the Society are published in the journal Ab presentation at special sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified stracts of papers presented to the American Mathematical Society in the issue below. For additional information, consult the meeting announcements and the list corresponding to that of the Notices which contains the program of the meeting, of special sessions. Meetings Abstract Program Meeting# Date Place Deadline Issue 876 * October 30-November 1 , 1992 Dayton, Ohio August 3 October 877 * November ?-November 8, 1992 Los Angeles, California August 3 October 878 * January 13-16, 1993 San Antonio, Texas OctoberS December (99th Annual Meeting) 879 * March 26-27, 1993 Knoxville, Tennessee January 5 March 880 * April9-10, 1993 Salt Lake City, Utah January 29 April 881 • Apnl 17-18, 1993 Washington, D.C. -

ENHANCED DYNKIN DIAGRAMS DONE RIGHT Introduction

ENHANCED DYNKIN DIAGRAMS DONE RIGHT V. MIGRIN AND N. VAVILOV Introduction In the present paper we draw the enhanced Dynkin diagrams of Eugene Dynkin and Andrei Minchenko [8] for senior exceptional types Φ = E6; E7 and E8 in a right way, `ala Rafael Stekolshchik [26], indicating not just adjacency, but also the signs of inner products. Two vertices with inner product −1 will be joined by a solid line, whereas two vertices with inner product +1 will be joined by a dotted line. Provisionally, in the absense of a better name, we call these creatures signed en- hanced Dynkin diagrams. They are uniquely determined by the root system Φ itself, up to [a sequence of] the following tranformations: changing the sign of any vertex and simultaneously switching the types of all edges adjacent to that vertex. Theorem 1. Signed enhanced Dynkin diagrams of types E6, E7 and E8 are depicted in Figures 1, 2 and 3, respectively. In this form such diagrams contain not just the extended Dynkin diagrams of all root subsystems of Φ | that they did already by Dynkin and Minchenko [8] | but also all Carter diagrams [6] of conjugacy classes of the corresponding Weyl group W (Φ). Theorem 2. The signed enhanced Dynkin diagrams of types E6, E7 and E8 contain all Carter|Stekolshchik diagrams of conjugacy classes of the Weyl groups W (E6), W (E7) and W (E8). In both cases the non-parabolic root subsystems, and the non-Coxeter conjugacy classes occur by exactly the same single reason, the exceptional behaviour of D4, where the fundamental subsystem can be rewritten as 4 A1, or as a 4-cycle, respectively, which constitutes one of the most manifest cases of the octonionic mathematics [2], so plumbly neglected by Vladimir Arnold (mathematica est omnis divisa in partes tres, see [1]). -

February 2012

LONDON MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER No. 411 February 2012 Society NEW YEAR (www.pugwash.org/) and ‘his Meetings role from the 1960s onward in HONOURS LIST 2012 rebuilding the mathematical ties and Events Congratulations to the following between European countries, who have been recognised in the particularly via the European 2012 New Year Honours list: Mathematical Society (EMS)’. Friday 24 February The ambassador went on to say, Mary Cartwright Knight Bachelor (KB) ‘[and] many people remember Lecture, London Simon Donaldson, FRS, Profes- the care you took when you [page 7] sor of Mathematics, Imperial were President of the Royal So- College London, for services to ciety, to cultivate closer ties with 26–30 March mathematics. [our] Académie des Sciences’. LMS Invited Lectures, Glasgow [page 11] 1 Commander of the Order of the MATHEMATICS Friday 27 April British Empire (CBE) POLICY ROUND-UP Women in Ursula Martin, Professor of Com- Mathematics Day, puter Science and Vice-Principal January 2012 of Science and Engineering, London [page 13] RESEARCH Queen Mary, University of Lon- Saturday 19 May don, for services to computer CMS registers ongoing concerns Poincaré Meeting, science. over EPSRC Fellowships London The Council for the Mathemati- Wednesday 6 June FRENCH HONOUR cal Sciences (CMS) has written Northern Regional to EPSRC to register its major Meeting, Newcastle FOR SIR MICHAEL continuing concerns about the [page 5] ATIYAH scope and operation of EPSRC Fellowships and other schemes Friday 29 June Former LMS President Sir Michael to support early-career research- Meeting and Hardy Atiyah, OM, FRS, FRSE has been ers in the mathematical sciences. -

P20d.Qxp Layout 1

Tiger Woods blames Guentzel’s goal medications for his lifts Penguins by arrest on DUI charge Predators 5-3 WEDNESDAY, MAY 1531, 2017 16 Borussia Dortmund fires Thomas Tuchel as coach Page 19 PARIS: France’s Alize Cornet returns the ball to Hungary’s Timea Babos during their tennis match at the Roland Garros 2017 French Open yesterday in Paris. — AFP Zverev, Konta flop at French Open PARIS: Alexander Zverev, the man seen as a potential French Guido Pella 6-2, 6-1, 6-4. “I love to be playing this tournament Open champion, crashed out in the first round yesterday while again after five years,” said 2009 US Open champion Del Potro, Johanna Konta became the second top 10 women’s player to who reached the quarter-finals in his last appearance in Paris exit. Zverev, just 20 and fresh from his sensational Rome Masters before blowing a two-set lead against Roger Federer. demolition of Novak Djokovic, slumped to a 6-4, 3-6, 6-4, 6-2 Taiwan’s Hsieh Su-Wei, the world number 109, stunned sev- defeat to Spain’s Fernando Verdasco, 13 years his senior. enth seed Konta 1-6, 7-6 (7/2), 6-4. “I played absolute shit, that’s why I lost,” said Zverev. Konta is the second top 10 woman to lose in the first three “But life goes on, it’s not a tragedy. In Rome I played fantastic, I days after world number one Angelique Kerber was also dumped won the tournament. Here I played bad, I lost first round. -

FOCUS August/September 2007

FOCUS August/September 2007 FOCUS is published by the Mathematical Association of America in January, February, FOCUS March, April, May/June, August/September, October, November, and December. Volume 27 Issue 6 Editor: Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College; [email protected] Managing Editor: Carol Baxter, MAA Inside: [email protected] Senior Writer: Harry Waldman, MAA hwald- 4 Mathematical Olympiad Winners Honored at the [email protected] U.S. Department of State Please address advertising inquiries to: 6 U.S. Team Places Fifth in IMO [email protected] 7 Math Circle Summer Teaching Training Institute President: Joseph Gallian 7 Robert Vallin Joins MAA as Associate Director for Student Activities First Vice President: Carl Pomerance, Second Vice President: Deanna Haunsperger, 8 Archives of American Mathematics Spotlight: The Isaac Jacob Secretary: Martha J. Siegel, Associate Schoenberg Papers Secretary: James J. Tattersall, Treasurer: John W. Kenelly 10 FOCUS on Students: Writing a Résumé Executive Director: Tina H. Straley 11 Attend ICME-11 in Monterrey, Mexico Director of Publications for Journals and 12 An Interview with Trachette Jackson Communications: Ivars Peterson 15 The Council on Undergraduate Research as a Resource FOCUS Editorial Board: Donald J. Albers; for Mathematicians Robert Bradley; Joseph Gallian; Jacqueline Giles; Colm Mulcahy; Michael Orrison; Pe- 16 2007 Award Winners for Distinguished Teaching ter Renz; Sharon Cutler Ross; Annie Selden; Hortensia Soto-Johnson; Peter Stanek; Ravi 18 MAA Awards and Prizes at MathFest 2007 Vakil. 20 In Memoriam Letters to the editor should be addressed to 21 Fond Memories of My Friend Deborah Tepper Haimo, 1921-2007 Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College, Dept. of Mathematics, Waterville, ME 04901, or by 22 “Teaching Us to Number Our Days” email to [email protected]. -

Annual Rpt 2004 For

I N S T I T U T E for A D V A N C E D S T U D Y ________________________ R E P O R T F O R T H E A C A D E M I C Y E A R 2 0 0 3 – 2 0 0 4 EINSTEIN DRIVE PRINCETON · NEW JERSEY · 08540-0631 609-734-8000 609-924-8399 (Fax) www.ias.edu Extract from the letter addressed by the Institute’s Founders, Louis Bamberger and Mrs. Felix Fuld, to the Board of Trustees, dated June 4, 1930. Newark, New Jersey. It is fundamental in our purpose, and our express desire, that in the appointments to the staff and faculty, as well as in the admission of workers and students, no account shall be taken, directly or indirectly, of race, religion, or sex. We feel strongly that the spirit characteristic of America at its noblest, above all the pursuit of higher learning, cannot admit of any conditions as to personnel other than those designed to promote the objects for which this institution is established, and particularly with no regard whatever to accidents of race, creed, or sex. TABLE OF CONTENTS 4·BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE 7·FOUNDERS, TRUSTEES AND OFFICERS OF THE BOARD AND OF THE CORPORATION 10 · ADMINISTRATION 12 · PRESENT AND PAST DIRECTORS AND FACULTY 15 · REPORT OF THE CHAIRMAN 20 · REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR 24 · OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR - RECORD OF EVENTS 31 · ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 43 · REPORT OF THE SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL STUDIES 61 · REPORT OF THE SCHOOL OF MATHEMATICS 81 · REPORT OF THE SCHOOL OF NATURAL SCIENCES 107 · REPORT OF THE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE 119 · REPORT OF THE SPECIAL PROGRAMS 139 · REPORT OF THE INSTITUTE LIBRARIES 143 · INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT 3 INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE The Institute for Advanced Study was founded in 1930 with a major gift from New Jer- sey businessman and philanthropist Louis Bamberger and his sister, Mrs. -

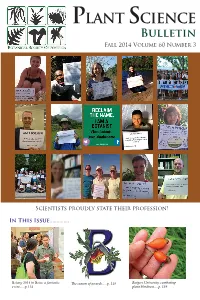

PLANT SCIENCE Bulletin Fall 2014 Volume 60 Number 3

PLANT SCIENCE Bulletin Fall 2014 Volume 60 Number 3 Scientists proudly state their profession! In This Issue.............. Botany 2014 in Boise: a fantastic The season of awards......p. 119 Rutgers University. combating event......p.114 plant blindness.....p. 159 From the Editor Reclaim the name: #Iamabotanist is the latest PLANT SCIENCE sensation on the internet! Well, perhaps this is a bit of BULLETIN an overstatement, but for those of us in the discipline, Editorial Committee it is a real ego boost and a bit of ground truthing. We do identify with our specialties and subdisciplines, Volume 60 but the overarching truth that we have in common Christopher Martine is that we are botanists! It is especially timely that (2014) in this issue we publish two articles directly relevant Department of Biology to reclaiming the name. “Reclaim” suggests that Bucknell University there was something very special in the past that Lewisburg, PA 17837 perhaps has lost its luster and value. A century ago [email protected] botany was a premier scientific discipline in the life sciences. It was taught in all the high schools and most colleges and universities. Leaders of the BSA Carolyn M. Wetzel were national leaders in science and many of them (2015) had their botanical roots in Cornell University, as Biology Department well documented by Ed Cobb in his article “Cornell Division of Health and University Celebrates its Botanical Roots.” While Natural Sciences Cornell is exemplary, many institutions throughout Holyoke Community College the country, and especially in the Midwest, were 303 Homestead Ave leading botany to a position of distinction in the Holyoke, MA 01040 development of U.S. -

Baker Et Al Online Appendices Word Version

Complete Generic Level Phylogenies of Palms (Arecaceae) with Comparisons of Supertree and Supermatrix Approaches William J. Baker, Vincent Savolainen, Conny B. Asmussen-Lange, Mark W. Chase, John Dransfield, Félix Forest, Madeline M. Harley, Natalie W. Uhl and Mark Wilkinson Online Appendices 1 Online Appendix 1. Genbank accession numbers for all sequences included in the supermatrix. Asterisks indicate the longer fragments of ms obtained by Lewis and Doyle (2001). Genus 18S atp B ITS mat K ms ndh F prk rbc L rpb 2 rps 16 trn D-trn T trn L-trn F trn Q-rps 16 Acanthophoenix - - - AM114691 AF249918* - AF453329 AM110234 AJ830020 AM116836 - AM113679 - Acoelorraphe - - - AM114579 - - - AM110197 - AM116782 - AM113627 - Acrocomia - AY044462 - AM114639 - AY044555 AJ831344 AM110212 AJ830151 AM116804 AY044506 AM113648 AY044602 Actinokentia - - - AM114661 - - AJ831222 AM110221 AJ830023 AM116815 - AM113659 - Actinorhytis - - - AM114659 AF455571 - AF453330 AJ829847 AJ830024 AM116814 - AM113658 - Adonidia - - - - - - AJ831224 AJ829848 AJ830193 - - - - Aiphanes - AY044463 - AM114641 - AY044556 AY601207 AJ404831 - AJ404953 AY044507 AJ404920 AY044603 Allagoptera - AY044468 - AM114635 AF249919* AY044564 AF453331 AJ404828 AJ830152 AJ240902 AY044515 AJ241311 AY044611 Alloschmidia - - - AM114666 - - AJ831225 AJ829849 AJ830026 AM116817 - AM113661 - Alsmithia - - - AM114711 - - AJ831226 AJ829850 AJ830027 AM116849 - AM113692 - Ammandra - - - AM114611 AF249920* - AF453332 AJ404838 AY543096 AJ404955 - AJ404922 - Aphandra AF406632 AY044458 - AM114612 - AY044532 -

P16 Layout 1

Hamilton reigns Berchelt retains at Silverstone to WBC title against cut13 Vettel lead ex-champion Miura MONDAY, JULY 17, 2017 14 Miazga’s late goal gives US first place in Gold Cup group Page 15 LONDON: Switzerland’s Roger Federer (L) and Croatia’s Marin Cilic pose with their trophies after Federer won their men’s singles final match, during the presentation on the last day of the 2017 Wimbledon Championships at The All England Lawn Tennis Club in Wimbledon, southwest London, yesterday. Roger Federer won 6-3, 6-1, 6-4. — AFP Federer wins record 8th Wimbledon LONDON: Roger Federer won a record eighth away. He had his left foot taped at the end of could get back. “Here am I today with the the best tennis of my life. I really want to slumped in his courtside chair in tears and in Wimbledon title and became the tourna- the second set but it was in vain as Federer eighth. It’s fantastic, if you keep believing you thank my team-they gave so much strength to obvious pain. The trainer and doctor were ment’s oldest champion yesterday with a became the first player since Bjorn Borg in can go far in your life.” me.” Beneath a star-studded Royal Box where summoned before Cilic hid his head in his tow- straight-sets victory over injury-hit Marin Cilic 1976 to win Wimbledon without dropping a Federer won his 18th Slam in Australia in Prince William and wife Kate rubbed shoulders el in a desperate attempt to compose himself.