Jews, Divorce and the French Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeffrey Haus

JEFFREY HAUS Director of Jewish Studies Associate Professor (269)-337-5789 (office) Departments of History and Religion (269)-337-5792 (fax) Kalamazoo College email: [email protected] 1200 Academy Street Kalamazoo, Michigan 49006 ACADEMIC TRAINING Ph.D., Brandeis University, Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies, May 1997. Dissertation: "The Practical Dimensions of Ideology: French Judaism, Jewish Education State in the Nineteenth Century" Specializations: The Jews of France, Modern Jewish History, Church and State in Europe Languages: French, Hebrew, German B.A., University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, 1986, with Distinction, Honors in History. Honors Thesis: "The Ford Administration's Policy Toward the Arab Boycott of Business" TEACHING APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor of History and Religion, Director of Jewish Studies, Kalamazoo College, 2009-present. Assistant Professor of History and Religion, Director of Jewish Studies, Kalamazoo College, 2005-09. Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Religious Studies, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2002-2005 Visiting Assistant Professor, Jewish Studies Program, Tulane University, 1999-2002 Lecturer, Department of Near Eastern & Judaic Studies, Brandeis University, 1998-1999 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, 1997-1998 Lecturer, University of Judaism, Los Angeles, 1996 Haus, p.2 PROFESSIONAL & ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE Director of Jewish Studies, Kalamazoo College, 2005-present. Chair, History Department, Kalamazoo College, July 2010-present Interim Chair, Religion Department, Kalamazoo College, Winter-Spring, 2010, Winter 2011. Faculty Advisor, Jewish Student Organization, Kalamazoo College, 2005-present. Admissions Committee, Kalamazoo College, 2006-2009. Summer Common Reading Committee, Kalamazoo College, 2006-7. Religion Search Committee, Kalamazoo College, June 2006-February 2007. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Introduction French Society in 1789 Historians working on the French Revolution have a problem. All of our attempts to find an explanation in terms of social groups or classes, or particular segments of society becoming powerfully activated, have fallen short. As one expert aptly expressed it: “the truth is we have no agreed general theory of why the French Revolution came about and what it was— and no prospect of one.”1 This gaping, causal void is cer- tainly not due to lack of investigation into the Revolution’s background and origins. If class conflict in the Marxist sense has been jettisoned, other ways of attributing the Revolution to social change have been ex- plored with unrelenting rigor. Of course, every historian agrees society was slowly changing and that along with the steady expansion of trade and the cities, and the apparatus of the state and armed forces, more (and more professional) lawyers, engineers, administrators, officers, medical staff, architects, and naval personnel were increasingly infusing and diversifying the existing order.2 Yet, no major, new socioeconomic pressures of a kind apt to cause sudden, dramatic change have been identified. The result, even some keen revisionists admit, is a “somewhat painful void.”3 Most historians today claim there was not one big cause but instead numerous small contributory impulses. One historian, stressing the absence of any identifiable overriding cause, likened the Revolution’s origins to a “multi- coloured tapestry of interwoven causal factors.”4 So- cial and economic historians embracing the “new social interpretation” identify a variety of difficulties that might have rendered eighteenth- century French society, at least in some respects, more fraught and vulnerable than earlier. -

Intermarriage and Jewish Leadership in the United States

Steven Bayme Intermarriage and Jewish Leadership in the United States There is a conflict between personal interests and collective Jewish welfare. As private citizens, we seek the former; as Jewish leaders, however, our primary concern should be the latter. Jewish leadership is entrusted with strengthening the collective Jewish endeavor. The principle applies both to external questions of Jewish security and to internal questions of the content and meaning of leading a Jewish life. Countercultural Messages Two decades ago, the American Jewish Committee (AJC) adopted a “Statement on Mixed Marriage.”1 The statement was reaffirmed in 1997 and continues to represent the AJC’s view regarding Jewish communal policy on this difficult and divisive issue. The document, which is nuanced and calls for plural approaches, asserts that Jews prefer to marry other Jews and that efforts at promoting endogamy should be encouraged. Second, when a mixed marriage occurs, the best outcome is the conversion of the non-Jewish spouse, thereby transforming a mixed marriage into an endogamous one. When conversion is not possible, efforts should be directed at encouraging the couple to raise their children exclusively as Jews. All three messages are countercultural in an American society that values egalitarianism, universalism, and multiculturalism. Preferring endogamy contradicts a universalist ethos of embracing all humanity. Encouraging conversion to Judaism suggests preference for one faith over others. Advocating that children be raised exclusively as Jews goes against multicultural diversity, which proclaims that having two faiths in the home is richer than having a single one. It is becoming increasingly difficult for Jewish leaders to articulate these messages. -

Untitled Remarks from “Köln, 30

Jewish Philosophical Politics in Germany, 1789–1848 the tauber institute series for the study of european jewry Jehuda Reinharz, General Editor Sylvia Fuks Fried, Associate Editor Eugene R. Sheppard, Associate Editor The Tauber Institute Series is dedicated to publishing compelling and innovative approaches to the study of modern European Jewish history, thought, culture, and society. The series features scholarly works related to the Enlightenment, modern Judaism and the struggle for emancipation, the rise of nationalism and the spread of antisemitism, the Holocaust and its aftermath, as well as the contemporary Jewish experience. The series is published under the auspices of the Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry— established by a gift to Brandeis University from Dr. Laszlo N. Tauber—and is supported, in part, by the Tauber Foundation and the Valya and Robert Shapiro Endowment. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com Sven-Erik Rose Jewish Philosophical Politics in Germany, 1789–1848 ChaeRan Y. Freeze and Jay M. Harris, editors Everyday Jewish Life in Imperial Russia: Select Documents, 1772–1914 David N. Myers and Alexander Kaye, editors The Faith of Fallen Jews: Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi and the Writing of Jewish History Federica K. Clementi Holocaust Mothers and Daughters: Family, History, and Trauma *Ulrich Sieg Germany’s Prophet: Paul de Lagarde and the Origins of Modern Antisemitism David G. Roskies and Naomi Diamant Holocaust Literature: A History and Guide *Mordechai -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

CROSSING BOUNDARY LINES: RELIGION, REVOLUTION, AND NATIONALISM ON THE FRENCH-GERMAN BORDER, 1789-1840 By DAWN LYNN SHEDDEN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Dawn Shedden 2 To my husband David, your support has meant everything to me 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As is true of all dissertations, my work would have been impossible without the help of countless other people on what has been a long road of completion. Most of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Sheryl Kroen, whose infinite patience and wisdom has kept me balanced and whose wonderful advice helped shape this project and keep it on track. In addition, the many helpful comments of all those on my committee, Howard Louthan, Alice Freifeld, Jessica Harland-Jacobs, Jon Sensbach, and Anna Peterson, made my work richer and deeper. Other scholars from outside the University of Florida have also aided me over the years in shaping this work, including Leah Hochman, Melissa Bullard, Lloyd Kramer, Catherine Griggs, Andrew Shennan and Frances Malino. All dissertations are also dependent on the wonderful assistance of countless librarians who help locate obscure sources and welcome distant scholars to their institutions. I thank the librarians at Eckerd College, George A. Smathers libraries at the University of Florida, the Judaica Collection in particular, Fürstlich Waldecksche Hofbibliothek, Wissenschaftliche Stadtsbibliothek Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg Universitätsbibliothek Mainz, Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz, Stadtarchiv Trier, and Bistumsarchiv Trier. The University of Florida, the American Society for Eighteenth- Century Studies, and Pass-A-Grille Beach UCC all provided critical funds to help me research and write this work. -

Bibliographical Contributions

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL CONTRIBUTIONS 2 UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES 1976 University of Kansas Publications Library Series, 40 Copy for the title-page of the projected third edition of Pierre-Louis Roederer's Adresse d'un constitutionnel aux constitutionnels (see first article) BIBLIOGRAPHICAL CONTRIBUTIONS 2 UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES Lawrence, Kansas 1976 PRINTED IN LAWRENCE, KANSAS, U.S.A., BY THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS PRINTING SERVICE Contents Pierre-Louis Roederer and the Adresse d'un Constitutionnel aux Constitutionnels (1835): Notes on a recent acquisition. By CHARLES K. WARNER The "Secret Transactions" of John Bowring and Charles I in the Isle of Wight: a Reappraisal. By ALLAN J. BUSCH Catesby, Curll, and Cook: or, The Librarian and the 18th Cen• tury English Book. By ALEXANDRA MASON Pierre-Louis Roederer and The Adresse d'un Constitutionnel Aux Constitutionnels (1835): Notes on a Recent Acquisition CHARLES K. WARNER In 1832, Louis-Philippe, King of the French since the July Revolution of 1830, appointed Count Pierre-Louis Roederer, an aging but still ener• getic notable of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, to the Chamber of Peers, the upper house of France's new parliament. In February 1835, during what was to be his eighty-second and last year, Roederer published a small pamphlet, Adresse d'un constitutionnel aux constitutionnels, which burst like an embarrassing bombshell in the middle of the worst ministerial crisis of the July Monarchy's early years.1 Briefly, Roederer's pamphlet fustigated the efforts of such parliamentary leaders as Thiers, De Broglie and Guizot to obtain a ministry in some degree responsible to parliament and, more immediately, the right for the cabinet to meet apart from the King. -

Southern Jewish History

SOUTHERN JEWISH HISTORY Journal of the Southern Jewish Historical Society Mark K. Bauman, Editor [email protected] Bryan Edward Stone, Managing Editor [email protected] Scott M. Langston, Primary Sources Section Editor [email protected] Stephen J. Whitfield, Book Review Editor [email protected] Jeremy Katz, Exhibit and Film Review Editor [email protected] Adam Mendelsohn, Website Review Editor [email protected] Rachel Heimovics Braun, Founding Managing Editor [email protected] 2 0 1 6 Volume 19 Southern Jewish History Editorial Board Robert Abzug Lance Sussman Ronald Bayor Ellen Umansky Karen Franklin Deborah Weiner Adam Meyer Daniel Weinfeld Stuart Rockoff Lee Shai Weissbach Stephen Whitfield Southern Jewish History is a publication of the Southern Jewish Historical Society available by subscription and a benefit of membership in the Society. The opinions and statements expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the journal or of the Southern Jewish Historical Society. Southern Jewish Historical Society OFFICERS: Ellen Umansky, President; Dan Puckett, Vice President and President Elect; Phyllis Leffler, Secretary; Les Bergen, Treasurer; Shari Rabin, Corresponding Secretary; Dale Rosengarten, Immediate Past President. BOARD OF TRUSTEES: Ronald Bayor, Perry Brickman, Michael R. Cohen, Bonnie Eisenman, Sol Kimerling, Peggy Pearlstein, Jim Pfeifer, Jay Silverberg, Jarrod Tanny, Teri Tillman; Bernard Wax, Board Member Emeritus; Rachel Reagler Schulman, Ex-Officio Board Member. For submission information and author guidelines, see http://www.jewishsouth .org/submission-information-and-guidelines-authors. For queries and all editorial matters: Mark K. Bauman, Editor, Southern Jewish History, 6856 Flagstone Way, Flowery Branch, GA 30542, e-mail: [email protected]. For journal subscriptions and advertising: Bryan Edward Stone, Managing Editor, PO Box 271432, Corpus Christi, TX 78427, e-mail: [email protected]. -

The First Exhibition of the Art Collection of the Jewish Community Berlin1

The First Exhibition of the Art Collection of the Jewish Community Berlin1 From the report on the opening day by Moritz Stern Out of the great wealth of precious material our collection contains, only part of it can be exhibited due to limited space: an exhibition, I assembled from Albert Wolf’s donation, from acquisitions made, and from loans from the Community with the addition of several library treasures2. A so-called “Guide through the Exhibition,” it is to be hoped, will soon provide the necessary orientation. For today, the following overview shall offer a kind of substitute. Only few antiquities from Palestine can be found in Europe. These are solely owed to excavations. Wolf managed to acquire several that give us insight into private life in ancient Palestine. Reminding us in its shape of the worship in the time of the older kingdom is an idolatry figure (Astarte) from clay, even though it might originate only from the Maccabean period. The subsequent period, when the Second Temple was still in existence, emerges before our mind’s eyes thanks to an oil lamp, also from clay. We can see the inventory of Palestinian houses in the Roman period through various valuable glasses, a small gold chain, a little bronze lion, and other items. A valuable coin collection gradually assembled by Wolf is transferring us into the public life of the Jewish state. It is an excellent visual and educational example for our laypeople, but also a treasure trove for the archeological science; since it forms a complement to the collections of the Münzkabinett (Numismatic Collection) in Berlin and the British Museum in London. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Tyranny of Tolerance: France, Religion, and the Conquest of Algeria, 1830-1870 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/52v9w979 Author Schley, Rachel Eva Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Tyranny of Tolerance: France, Religion, and the Conquest of Algeria, 1830-1870 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Rachel Eva Schley 2015 © Copyright by Rachel Eva Schley 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Tyranny of Tolerance: France, Religion, and the Conquest of Algeria, 1830-1870 by Rachel Eva Schley Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Caroline Cole Ford, Co-chair Professor Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Co-chair “The Tyranny of Tolerance” examines France’s brutal entry into North Africa and a foundational yet unexplored tenet of French colonial rule: religious tolerance. By selectively tolerating and thereby emphasizing confessional differences, this colonial strategy was fundamentally about reaffirming French authority. It did so by providing colonial leaders with a pliant, ethical and practical framework to both justify and veil the costs of a violent conquest and by eliding ethnic and regional divisions with simplistic categories of religious belonging. By claiming to protect mosques and synagogues and by lauding their purported respect for venerated figures, military leaders believed they would win the strategic support of local communities—and therefore secure the fate of France on African soil. Scholars have long focused on the latter period of French Empire, offering metropole-centric narratives of imperial development. -

Fine Judaica: Printed Books, Manuscripts, Holy Land Maps & Ceremonial Objects, to Be Held June 23Rd, 2016

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts, holy land maps & Ceremonial obJeCts K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, Ju ne 23r d, 2016 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 147 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . PRINTED BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, HOLY LAND MAPS & CEREMONIAL OBJECTS INCLUDING: Important Manuscripts by The Sinzheim-Auerbach Rabbinic Dynasty Deaccessions from the Rare Book Room of The Hebrew Theological College, Skokie, Ill. Historic Chabad-related Documents Formerly the Property of the late Sam Kramer, Esq. Autograph Letters from the Collection of the late Stuart S. Elenko Holy Land Maps & Travel Books Twentieth-Century Ceremonial Objects The Collection of the late Stanley S. Batkin, Scarsdale, NY ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 23rd June, 2016 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 19th June - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 20th June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 21st June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 22nd June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Consistoire” Sale Number Sixty Nine Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th Street, 12th Floor, New York, NY 10001 • Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web Site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . -

AMPAL—American Israel Corporation, 437

Index AMPAL—American Israel Corporation, Alberts v. State of California, 37n 437 Albrecht, A., 291 Aaron v. Cooper, 45n Alcorn A. and M. College, 56 Abbady, Isaac A., 530 Aldanov, Mark (Landau), 256 Abbreviations, list of, 419-20 Alexander Kohut Memorial Foundation, Aberg, Einar, 280 422 Abrahamov, Levy, 388 Alexandria Yachting Club, 397 Abrahams, Sidney, 245 Algerian National Liberation Front, 345, Abramov, Alexander N., 323 505 Abrams, Charles, 74, 77, 79 Aliyah, 355 Academy for Higher Jewish Learning, All-American Conference to Combat 425 Communism, 516 Academy of Languages (Brazil), 505 Allen, James E., Jr., 97 Acervo, 408 Allen University, 59 Acheson, Dean, 25, 26, 207, 213 Allensbach Institute for Public Opinion Achour, Habib, 349 Research, 290 Acker, Achille van, 257 Alliance Israelite Universelle, 152, 256, L'Action Sociale par l'Habitat, 252 350, 354, 359, 364, 365, 398, 399, 504, Aczel, Jamas, 336 517 Adams, Theodore L., 122 Alliance Israelite Universelle Teachers Adams Newark Theater v. Newark, 37n Union, 365 Adenauer, Konrad, 288, 289, 306 All-Russian Congress of the Workers of Adkins v. School Bd. of City of Newport Art, 321 News, 67n Allschoff, Ewald, 301 Adler, Adolphe, 474 Almond, J. Lindsay, Jr., 92 Adler, H. G., 290, 301 Alpha Epsilon Phi, 432 Adler, Peter, 297 Alpha Epsilon Pi Fraternity, 432 Adult Jewish Leadership, 458 Alpha Omega Fraternity, 432 Agudah News Reporter, 458 Altmann, Alexander, 301 Agudas Israel (Great Britain), 243 Amalgamated Meat Cutters v. NLRB, Agudas Israel World Organization, 208, 29n 283, 312, -

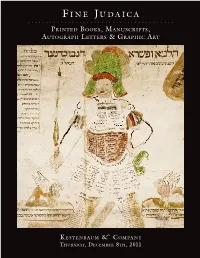

Fi N E Ju D a I

F i n e Ju d a i C a . pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s & gr a p h i C ar t K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y th u r s d a y , de C e m b e r 8t h , 2011 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 334 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS & GRA P HIC ART Featuring: Books from Jews’ College Library, London ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 8th December, 2011 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 4th December - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 5th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 6th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday 7th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale. This Sale may be referred to as: “Omega” Sale Number Fifty-Three Illustrated Catalogues: $35 (US) * $42 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y .