ECA Legal Bulletin 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Can Replace Xavi? a Passing Motif Analysis of Football Players

Who can replace Xavi? A passing motif analysis of football players. Javier Lopez´ Pena˜ ∗ Raul´ Sanchez´ Navarro y Abstract level of passing sequences distributions (cf [6,9,13]), by studying passing networks [3, 4, 8], or from a dy- Traditionally, most of football statistical and media namic perspective studying game flow [2], or pass- coverage has been focused almost exclusively on goals ing flow motifs at the team level [5], where passing and (ocassionally) shots. However, most of the dura- flow motifs (developed following [10]) were satis- tion of a football game is spent away from the boxes, factorily proven by Gyarmati, Kwak and Rodr´ıguez passing the ball around. The way teams pass the to set appart passing style from football teams from ball around is the most characteristic measurement of randomized networks. what a team’s “unique style” is. In the present work In the present work we ellaborate on [5] by ex- we analyse passing sequences at the player level, us- tending the flow motif analysis to a player level. We ing the different passing frequencies as a “digital fin- start by breaking down all possible 3-passes motifs gerprint” of a player’s style. The resulting numbers into all the different variations resulting from labelling provide an adequate feature set which can be used a distinguished node in the motif, resulting on a to- in order to construct a measure of similarity between tal of 15 different 3-passes motifs at the player level players. Armed with such a similarity tool, one can (stemming from the 5 motifs for teams). -

Cite It Like This

e-ISSN: 2316-932X DOI: 10.5585/podium.v8i1.306 Received: 28/02/2018 Approved: 18/08/2018 Organização: Comitê Científico Interinstitucional Scientifc Editor: Júlio Araujo Carneiro da Cunha Evaluation: Double Blind Review pelo SEER/OJS SPORTS ACCOUNTING: AN ANALYSIS OF BRAZILIAN SOCCER CLUBS REVENUE SEGREGATION IN ADEQUACY TO NBC ITG 2003 1 Danielly Marques Frazão 2 Arthur do Nascimento Ferreira Barros 3Ana Lúcia Fontes de Souza 4Maria Cleonice de Oliveira Pereira ABSTRACT This article aims to analyze the financial statements of the 20 football clubs of the 2018’s Brazilian first division championship, in order to identify how the clubs are segregating the revenues related to the professional sports activity in their 2017’s financial statements, according to the Interpretação Técnica Geral 2003. The content analysis technique was used, which consists of perceiving the existence or the lack of information about a specific issue. Data were collected on the websites of participating sample clubs shortly after the deadline for disclosure of the mandatory financial statements. It was perceived that most of the clubs segregate from professional sports activities (87.5%) and discriminate by the nature of revenue between ticketing sales, sponsorship, television, transfer of athletes, among others (80%). In addition, clubs with high disclosure levels and good quality information had a better sporting performance than those who have not. However, clubs still do not meet the obligation of Interpretação Técnica Geral 2003 even after 4 years since it has been publicized. Moreover, there is a lack of comparability between the statements and the quality of the information disclosed, essential aspects for the users. -

Manchester United Make Maguire World's Most Expensive Defender

Sports Tuesday, August 6, 2019 13 Manchester United make Maguire world’s most expensive defender AFP home to Chelsea on Sunday and United manager land reached the semi-finals for the first time LONDON Ole Gunnar Solskjaer is confident he will live up to since 1990. his hefty price tag. United were interested in his signature last Three things MANCHESTER United signed Harry Maguire from “Harry is one of the best centre-backs in the summer, but baulked at Leicester’s asking price. Leicester on Monday for a reported £80 million fee game today and I am delighted we have secured his A year on and with the heart of their defence that makes the England centre-back the world’s signature,” he said. brutally exposed in finishing sixth in the Premier about Harry most expensive defender. “He is a great reader of the game and has a League last season to miss out on Champions United have secured Maguire on a six-year con- strong presence on the pitch, with the ability to League qualification, the Red Devils finally paid the tract with an option for a further 12-month extension. remain calm under pressure - coupled with his fee the Foxes’ demanded. AFP ed academy manager John The £75 million Liverpool paid for Virgil composure on the ball and a huge presence in both Solskjaer had made strengthening central de- LONDON Pemberton switched him to van Dijk in 2018 was the previous record fee for boxes - I can see he will fit well into this group both fence a priority, with that need only becoming more central defence, saying his a defender. -

Topps - UEFA Champions League Match Attax 2015/16 (08) - Checklist

Topps - UEFA Champions League Match Attax 2015/16 (08) - Checklist 2015-16 UEFA Champions League Match Attax 2015/16 Topps 562 cards Here is the complete checklist. The total of 562 cards includes the 32 Pro11 cards and the 32 Match Attax Live code cards. So thats 498 cards plus 32 Pro11, plus 32 MA Live and the 24 Limited Edition cards. 1. Petr Ĉech (Arsenal) 2. Laurent Koscielny (Arsenal) 3. Kieran Gibbs (Arsenal) 4. Per Mertesacker (Arsenal) 5. Mathieu Debuchy (Arsenal) 6. Nacho Monreal (Arsenal) 7. Héctor Bellerín (Arsenal) 8. Gabriel (Arsenal) 9. Jack Wilshere (Arsenal) 10. Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain (Arsenal) 11. Aaron Ramsey (Arsenal) 12. Mesut Özil (Arsenal) 13. Santi Cazorla (Arsenal) 14. Mikel Arteta (Arsenal) - Captain 15. Olivier Giroud (Arsenal) 15. Theo Walcott (Arsenal) 17. Alexis Sánchez (Arsenal) - Star Player 18. Laurent Koscielny (Arsenal) - Defensive Duo 18. Per Mertesacker (Arsenal) - Defensive Duo 19. Iker Casillas (Porto) 20. Iván Marcano (Porto) 21. Maicon (Porto) - Captain 22. Bruno Martins Indi (Porto) 23. Aly Cissokho (Porto) 24. José Ángel (Porto) 25. Maxi Pereira (Porto) 26. Evandro (Porto) 27. Héctor Herrera (Porto) 28. Danilo (Porto) 29. Rúben Neves (Porto) 30. Gilbert Imbula (Porto) 31. Yacine Brahimi (Porto) - Star Player 32. Pablo Osvaldo (Porto) 33. Cristian Tello (Porto) 34. Alberto Bueno (Porto) 35. Vincent Aboubakar (Porto) 36. Héctor Herrera (Porto) - Midfield Duo 36. Gilbert Imbula (Porto) - Midfield Duo 37. Joe Hart (Manchester City) 38. Bacary Sagna (Manchester City) 39. Martín Demichelis (Manchester City) 40. Vincent Kompany (Manchester City) - Captain 41. Gaël Clichy (Manchester City) 42. Elaquim Mangala (Manchester City) 43. Aleksandar Kolarov (Manchester City) 44. -

Vocabulário Do Futebol Na Mídia Impressa: O Glossário Da Bola

JOÃO MACHADO DE QUEIROZ VOCABULÁRIO DO FUTEBOL NA MÍDIA IMPRESSA: O GLOSSÁRIO DA BOLA Tese apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista, para a obtenção do Título de Doutor em Letras (Área de Conhecimento: Filologia e Lingüística Portuguesa). Orientador: Prof. Dr. Odilon Helou Fleury Curado ASSIS 2005 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA (Catalogação elaborada por Miriam Fenner R. Lucas – CRB/9:268 Biblioteca da UNIOESTE – Campus de Foz do Iguaçu) Q3 QUEIROZ, João Machado de Vocabulário do futebol na mídia impressa: o glossário da bola / João Machado de Queiroz. - Assis, SP, 2005. 4 v. (948f.) Orientador: Odilon Helou Fleury Curado, Dr. Dissertação (Doutorado) – Universidade Estadual Paulista. 1. Lingüística. 2. Filologia: Lexicologia . 3. Futebol: Mídia impressa brasileira: Vocabulário. 4. Linguagem do futebol: Neologismos: Glossá- rio. I. Título. CDU 801.3:796.33(81) JOÃO MACHADO DE QUEIROZ VOCABULÁRIO DO FUTEBOL NA MÍDIA IMPRESSA: O GLOSSÁRIO DA BOLA COMISSÃO JULGADORA TESE PARA OBTENÇÃO DO TÍTULO DE DOUTOR Faculdade de Ciências e Letras - UNESP Área de Conhecimento: Filologia e Lingüística Portuguesa Presidente e Orientador Dr. Odilon Helou Fleury Curado 2º Examinador Dra. Jeane Mari Sant’Ana Spera 3º Examinador Dra. Antonieta Laface 4º Examinador Dra. Marlene Durigan 5º Examinador Dr. Antonio Luciano Pontes Assis, de de 2005 A Misue, esposa Por compartilhar as dificuldades e alegrias da vida A meus filhos Keyla e Fernando Por me incentivarem a lutar A meus netos Luanna e João Henrique Por me presentearem com momentos de grande alegria AGRADECIMENTOS Ao Prof. Odilon Helou Fleury Curado pela orientação a mim dedicada. Ao Prof. Pedro Caruso, estimado professor e amigo, que inicialmente me recebeu como orientando, pelo apoio e conselhos inestimáveis, sem os quais não teria concluído este trabalho. -

Iii. Administración Local

BOCM BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID Pág. 468 LUNES 21 DE MARZO DE 2011 B.O.C.M. Núm. 67 III. ADMINISTRACIÓN LOCAL AYUNTAMIENTO DE 17 MADRID RÉGIMEN ECONÓMICO Agencia Tributaria Madrid Subdirección General de Recaudación En los expedientes que se tramitan en esta Subdirección General de Recaudación con- forme al procedimiento de apremio, se ha intentado la notificación cuya clave se indica en la columna “TN”, sin que haya podido practicarse por causas no imputables a esta Administra- ción. Al amparo de lo dispuesto en el artículo 112 de la Ley 58/2003, de 17 de diciembre, Ge- neral Tributaria (“Boletín Oficial del Estado” número 302, de 18 de diciembre), por el presen- te anuncio se emplaza a los interesados que se consignan en el anexo adjunto, a fin de que comparezcan ante el Órgano y Oficina Municipal que se especifica en el mismo, con el obje- to de serles entregada la respectiva notificación. A tal efecto, se les señala que deberán comparecer en cualquiera de las Oficinas de Atención Integral al Contribuyente, dentro del plazo de los quince días naturales al de la pu- blicación del presente anuncio en el BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID, de lunes a jueves, entre las nueve y las diecisiete horas, y los viernes y el mes de agosto, entre las nueve y las catorce horas. Quedan advertidos de que, transcurrido dicho plazo sin que tuviere lugar su compare- cencia, se entenderá producida la notificación a todos los efectos legales desde el día si- guiente al del vencimiento del plazo señalado. -

Background of Purchase Intention of Brazilian Soccer Clubfans

Global Journal of Management and Business Research Marketing Volume 13 Issue 7 Version 1.0 Year 2013 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4588 & Print ISSN: 0975-5853 Background of Purchase Intention of Brazilian Soccer Club Fans By Fernando de Oliveira Santini, Wagner Junior Ladeira & Clécio Falcão Araujo University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil Abstract - Studies about purchase intention have grown in the marketing area. This is so especially for those seeking to associate loyalty and brand image. Within this context, this paper has sought to analyze the background of purchase intention of soccer club sport products. Then, to apply a descriptive research with 1056 respondents who are fans. The data collected were analyzed using a set of techniques from Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The results of this research show that the intension of buying is more directly associated to loyalty to the brand rather than the actual image of the soccer club. It was evident the psychological commitment, the emotional attachment and the recognition or association to the brand antecede the purchase intention of sports articles made available by the soccer clubs. In conclusion, the final consideration and academic and managerial recommendations were expounded upon. Keywords : perceived advertising spending, price promotion, public relations, corporate reputation, brand equity. GJMBR-E Classification : JEL Code: D71, D69 BackgroundofPurchaseIntentionofBrazilianSoccerClubFans Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2013. Fernando de Oliveira Santini, Wagner Junior Ladeira & Clécio Falcão Araujo. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

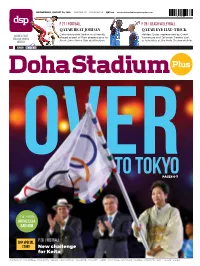

New Challenge for Keita

WEDNESDAY, AuguSt 24, 2016 VOLuME XI ISSuE NO.29 QR2.00 www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com P 27 | FOOTBALL P 28 | BEACH VOLLEYBALL QATAR BEAT JORDAN QATAR EYE HAT-TRICK QATAR’S FIRST Qatar overcome Jordan in a friendly Holders Qatar, represented by Cherif ENGLISH SPORTS played as part of their preparations for Younousse and Jefferson Pereira, start WEEKLY Asian Zone World Cup qualification. as favourites at the Arab Championship. FOLLOW US OVER TO TOKYO PAGES 6-7 P 20 | POSTER MUTAZ ESSA BARSHIM P 26 | FOOTBALL DSP SPECIAL STORY New challenge for Keita UK £1, Europe €2 | Oman 200 Baisas | Bahrain 200 Fils | Egypt LE 2 | Lebanon 3,000 Livre | Kuwait 250 Fils | Morocco Dh 6 | UAEDh 5 | Yemen 75 Riyals | Sudan 1 Pound | KSA 2 Riyals | Jordan 500 Fils | Iraq $1 | Palestine $1 | Syria LS 20 www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com | Wednesday, August 24, 2016 www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com 3 EXCITEMENT NOW JUST A TOUCH AWAY OutlookThe writer can be contacted at [email protected] Mutaz, Akram make history as Aspire shows the way forward ĈĈThe best preparation for tomorrow pollution and the gunmen from ‘crime-ravaged Liga club when he donned the colours of Sporting is doing your best today favelas’ didn’t shoot down anybody! Gijon against Athletic Bilbao last Sunday. Rio not only overcame all such fears, but also I’m sure their monumental achievements will LL’S well that ends well, they say. The Rio managed to tide over other crises, including the inspire a lot of youngsters in our country. Hearty Olympics might’ve ended in a blaze of suspension of the country’s president. -

Constructing Artworks. Issues of Authorship and Articulation Around Seydou Keïta’S Photographs

Nordic Journal of African Studies 17(1): 34–46 (2008) Constructing artworks. Issues of Authorship and Articulation around Seydou Keïta’s Photographs. ALESSANDRO JEDLOWSKI University of Naples, Italy ABSTRACT This essay focuses on Seydou Keïta’s work, and on the way in which this work has been received and conceptualized within both the African and the Western context. These photographs have a long history of geographical and cultural displacement that has deeply influenced their status, as well as the status of the people who engaged with them. The essay follows the development of this history, dealing with the processes of construction of Seydou Keïta as an author and of his photographs as international acclaimed pieces of art. Keywords: Seydou Keita, African photography, African Contemporary Art, Authorship INTRODUCTION This essay focuses on Seydou Keïta’s work, and on the way in which the work of this Malian photographer has been received and conceptualized within both the African and the Western context. Keïta’s photographs have a long history of geographical and cultural displacement that has deeply influenced their status, as well as the status of the people who engaged with them. From a photographic studio in Bamako in the 1950’s, these portraits moved to the houses of their purchasers. At least thirty years later, some negatives moved from Keïta’s personal archive to an exhibition in the Centre for African Art of New York. Attracted by the aesthetical beauty of these portraits, André Magnin bought some negatives for the biggest collection of Contemporary African Art, the Pigozzi Collection. Finally, only few years ago, the Pigozzi Collection donated some of the photographs it owns to the National Museum of Bamako. -

Iii Copa Internacional Ipiranga De Fútbol Sub-20 Edición 2018

III COPA INTERNACIONAL IPIRANGA DE FÚTBOL SUB-20 EDICIÓN 2018 Organización y Realización - Federación Gaúcha de Fútbol - REGLAMENTO Artículo 1º - La III Copa Internacional Ipiranga de Fútbol Sub-20 , en adelante denominada, simplemente, COPA INTERNACIONAL IPIRANGA SUB-20 la promueve, organiza y dirige la Federación Gaúcha de Fútbol (FGF), a través de su Comisión Organizadora , iniciando el día 30 de noviembre y finalizando el día 16 de diciembre de 2018. Artículo 2º - La Comisión Organizadora de la COPA INTERNACIONAL IPIRANGA SUB-20 será la única responsable por aclaraciones, referentes a asuntos relativos a la competición, constituida por los siguientes miembros de la FGF, como sigue: DIRECCIÓN GENERAL Francisco Novelletto Neto Presidente de la FGF Luciano Dahmer Hocsman 1º Vicepresidente de la FGF Nilo Job 2º Vicepresidente de la FGF COORDINACIÓN TÉCNICA Director ejecutivo Luiz Fernando Gomes Moreira Coordinador General Clóvis de Oliveira Martins 2 Asesores Emílio Mário de la Silva - Josinara Ramos - Yuri de Oliveira Teixeira - Ana Cristina Oliveira Marketing y comunicación Vanessa Veiverberg Médico Dr. Ivan Pacheco TRIBUNAL DE PENAS DEPORTIVAS Artículo 3º - El “Tribunal de Penas Deportivas” de la COPA INTERNACIONAL IPIRANGA SUB-20 será el único responsable por juicios referentes a la interpretación del Reglamento de la competición e inscripciones de atletas, como también, juzgar infracciones disciplinarias deportivas, constituido por los siguientes miembros: - Dr. Carlos Schneider – Presidente - Dr. Alberto Lopes Franco - Miembro Técnico - Dr. Renan Cardoso - Miembro Técnico - Josinara Ramos - Secretaria § Único - El “Tribunal de Penas Deportivas” de la COPA INTERNACIONAL IPIRANGA SUB-20 se reunirá 01 (una) vez a la semana, ordinariamente, para juzgar casos que vengan a ocurrir en el transcurso de la competición y extraordinariamente, a cualquier momento, conforme la necesidad. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Contextus – Revista Contemporânea de Economia e Gestão ISSN: 1678-2089 ISSN: 2178-9258 [email protected] Universidade Federal do Ceará Brasil Simão Gonçalves, Rafael; Cruz Mendes, Renato; Medeiros Henriques, Flávio; Moreira Tavares, Gustavo The influence of sports performance on economic-financial performance: An analysis of Brazilian soccer clubs from 2013 to 2017 Contextus – Revista Contemporânea de Economia e Gestão, vol. 18, 2020, -, pp. 239-250 Universidade Federal do Ceará Brasil DOI: https://doi.org/10.19094/contextus.2020.44392 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=570764039017 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Contextus – Contemporary Journal of Economics and Management (2020), 18(17), 239-250 Contextus – Contemporary Journal of Economics and Management ISSN 1678-2089 FEDERAL UNIVERSITY ISSNe 2178-9258 OF CEARÁ www.periodicos.ufc.br/contextus The influence of sports performance on economic-financial performance: An analysis of Brazilian soccer clubs from 2013 to 2017 A influência do rendimento esportivo no desempenho econômico-financeiro: Uma análise com clubes de futebol brasileiros durante 2013-2017 La influencia del rendimiento deportivo en el rendimiento económico-financiero: Un análisis con clubes de fútbol brasileños durante 2013-2017 https://doi.org/10.19094/contextus.2020.44392 Rafael Simão Gonçalves ABSTRACT https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1824-9678 This study examined the relationship between sports performance and economic-financial Professor at the Federal Institute of Rio de performance in the subsequent year based on the revenue sources of Brazilian sports clubs Janeiro (IFRJ) from 2013 to 2017. -

Uefa Champions League

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2021/22 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS (First leg: 0-3) Stadion Maksimir - Zagreb Wednesday 25 August 2021 GNK Dinamo Zagreb 21.00CET (21.00 local time) FC Sheriff Tiraspol Play-off, Second leg Last updated 25/08/2021 14:27CET UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Previous meetings 2 Legend 4 1 GNK Dinamo Zagreb - FC Sheriff Tiraspol Wednesday 25 August 2021 - 21.00CET (21.00 local time) Match press kit Stadion Maksimir, Zagreb Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers FC Sheriff Tiraspol - GNK Traoré 45, 80, 17/08/2021 PO 3-0 Tiraspol Dinamo Zagreb Kolovos 54 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers FC Sheriff Tiraspol - GNK 0-3 Fernandes 10, 07/08/2013 QR3 Tiraspol Dinamo Zagreb agg: 0-4 Soudani 27, Čop 61 GNK Dinamo Zagreb - FC Sheriff 30/07/2013 QR3 1-0 Zagreb Rukavina 89 Tiraspol UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers GNK Dinamo Zagreb - FC Sheriff 4-0 Vida 16, Bećiraj 34, 08/08/2012 QR3 Zagreb Tiraspol agg: 5-0 Čop 78, Ibáñez 87 FC Sheriff Tiraspol - GNK 01/08/2012 QR3 0-1 Tiraspol Bećiraj 14 Dinamo Zagreb UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers 1-1 GNK Dinamo Zagreb - FC Sheriff Sammir 55 (P); 04/08/2010 QR3 agg: 2-2 (aet, 5- Zagreb Tiraspol Volkov 16 6 pens) FC Sheriff Tiraspol - GNK Dinamo 28/07/2010 QR3 1-1 Tiraspol Erokhin 35; Sammir 3 Zagreb Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA GNK Dinamo Zagreb 3 2 1 0 4 2 1 1 0 0 0 0 7 4 2 1 11 5 FC Sheriff Tiraspol