Constructing Artworks. Issues of Authorship and Articulation Around Seydou Keïta’S Photographs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Can Replace Xavi? a Passing Motif Analysis of Football Players

Who can replace Xavi? A passing motif analysis of football players. Javier Lopez´ Pena˜ ∗ Raul´ Sanchez´ Navarro y Abstract level of passing sequences distributions (cf [6,9,13]), by studying passing networks [3, 4, 8], or from a dy- Traditionally, most of football statistical and media namic perspective studying game flow [2], or pass- coverage has been focused almost exclusively on goals ing flow motifs at the team level [5], where passing and (ocassionally) shots. However, most of the dura- flow motifs (developed following [10]) were satis- tion of a football game is spent away from the boxes, factorily proven by Gyarmati, Kwak and Rodr´ıguez passing the ball around. The way teams pass the to set appart passing style from football teams from ball around is the most characteristic measurement of randomized networks. what a team’s “unique style” is. In the present work In the present work we ellaborate on [5] by ex- we analyse passing sequences at the player level, us- tending the flow motif analysis to a player level. We ing the different passing frequencies as a “digital fin- start by breaking down all possible 3-passes motifs gerprint” of a player’s style. The resulting numbers into all the different variations resulting from labelling provide an adequate feature set which can be used a distinguished node in the motif, resulting on a to- in order to construct a measure of similarity between tal of 15 different 3-passes motifs at the player level players. Armed with such a similarity tool, one can (stemming from the 5 motifs for teams). -

Topps - UEFA Champions League Match Attax 2015/16 (08) - Checklist

Topps - UEFA Champions League Match Attax 2015/16 (08) - Checklist 2015-16 UEFA Champions League Match Attax 2015/16 Topps 562 cards Here is the complete checklist. The total of 562 cards includes the 32 Pro11 cards and the 32 Match Attax Live code cards. So thats 498 cards plus 32 Pro11, plus 32 MA Live and the 24 Limited Edition cards. 1. Petr Ĉech (Arsenal) 2. Laurent Koscielny (Arsenal) 3. Kieran Gibbs (Arsenal) 4. Per Mertesacker (Arsenal) 5. Mathieu Debuchy (Arsenal) 6. Nacho Monreal (Arsenal) 7. Héctor Bellerín (Arsenal) 8. Gabriel (Arsenal) 9. Jack Wilshere (Arsenal) 10. Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain (Arsenal) 11. Aaron Ramsey (Arsenal) 12. Mesut Özil (Arsenal) 13. Santi Cazorla (Arsenal) 14. Mikel Arteta (Arsenal) - Captain 15. Olivier Giroud (Arsenal) 15. Theo Walcott (Arsenal) 17. Alexis Sánchez (Arsenal) - Star Player 18. Laurent Koscielny (Arsenal) - Defensive Duo 18. Per Mertesacker (Arsenal) - Defensive Duo 19. Iker Casillas (Porto) 20. Iván Marcano (Porto) 21. Maicon (Porto) - Captain 22. Bruno Martins Indi (Porto) 23. Aly Cissokho (Porto) 24. José Ángel (Porto) 25. Maxi Pereira (Porto) 26. Evandro (Porto) 27. Héctor Herrera (Porto) 28. Danilo (Porto) 29. Rúben Neves (Porto) 30. Gilbert Imbula (Porto) 31. Yacine Brahimi (Porto) - Star Player 32. Pablo Osvaldo (Porto) 33. Cristian Tello (Porto) 34. Alberto Bueno (Porto) 35. Vincent Aboubakar (Porto) 36. Héctor Herrera (Porto) - Midfield Duo 36. Gilbert Imbula (Porto) - Midfield Duo 37. Joe Hart (Manchester City) 38. Bacary Sagna (Manchester City) 39. Martín Demichelis (Manchester City) 40. Vincent Kompany (Manchester City) - Captain 41. Gaël Clichy (Manchester City) 42. Elaquim Mangala (Manchester City) 43. Aleksandar Kolarov (Manchester City) 44. -

Iii. Administración Local

BOCM BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID Pág. 468 LUNES 21 DE MARZO DE 2011 B.O.C.M. Núm. 67 III. ADMINISTRACIÓN LOCAL AYUNTAMIENTO DE 17 MADRID RÉGIMEN ECONÓMICO Agencia Tributaria Madrid Subdirección General de Recaudación En los expedientes que se tramitan en esta Subdirección General de Recaudación con- forme al procedimiento de apremio, se ha intentado la notificación cuya clave se indica en la columna “TN”, sin que haya podido practicarse por causas no imputables a esta Administra- ción. Al amparo de lo dispuesto en el artículo 112 de la Ley 58/2003, de 17 de diciembre, Ge- neral Tributaria (“Boletín Oficial del Estado” número 302, de 18 de diciembre), por el presen- te anuncio se emplaza a los interesados que se consignan en el anexo adjunto, a fin de que comparezcan ante el Órgano y Oficina Municipal que se especifica en el mismo, con el obje- to de serles entregada la respectiva notificación. A tal efecto, se les señala que deberán comparecer en cualquiera de las Oficinas de Atención Integral al Contribuyente, dentro del plazo de los quince días naturales al de la pu- blicación del presente anuncio en el BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID, de lunes a jueves, entre las nueve y las diecisiete horas, y los viernes y el mes de agosto, entre las nueve y las catorce horas. Quedan advertidos de que, transcurrido dicho plazo sin que tuviere lugar su compare- cencia, se entenderá producida la notificación a todos los efectos legales desde el día si- guiente al del vencimiento del plazo señalado. -

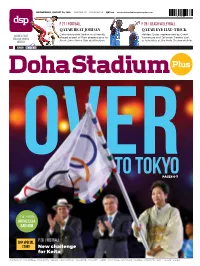

New Challenge for Keita

WEDNESDAY, AuguSt 24, 2016 VOLuME XI ISSuE NO.29 QR2.00 www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com P 27 | FOOTBALL P 28 | BEACH VOLLEYBALL QATAR BEAT JORDAN QATAR EYE HAT-TRICK QATAR’S FIRST Qatar overcome Jordan in a friendly Holders Qatar, represented by Cherif ENGLISH SPORTS played as part of their preparations for Younousse and Jefferson Pereira, start WEEKLY Asian Zone World Cup qualification. as favourites at the Arab Championship. FOLLOW US OVER TO TOKYO PAGES 6-7 P 20 | POSTER MUTAZ ESSA BARSHIM P 26 | FOOTBALL DSP SPECIAL STORY New challenge for Keita UK £1, Europe €2 | Oman 200 Baisas | Bahrain 200 Fils | Egypt LE 2 | Lebanon 3,000 Livre | Kuwait 250 Fils | Morocco Dh 6 | UAEDh 5 | Yemen 75 Riyals | Sudan 1 Pound | KSA 2 Riyals | Jordan 500 Fils | Iraq $1 | Palestine $1 | Syria LS 20 www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com | Wednesday, August 24, 2016 www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com 3 EXCITEMENT NOW JUST A TOUCH AWAY OutlookThe writer can be contacted at [email protected] Mutaz, Akram make history as Aspire shows the way forward ĈĈThe best preparation for tomorrow pollution and the gunmen from ‘crime-ravaged Liga club when he donned the colours of Sporting is doing your best today favelas’ didn’t shoot down anybody! Gijon against Athletic Bilbao last Sunday. Rio not only overcame all such fears, but also I’m sure their monumental achievements will LL’S well that ends well, they say. The Rio managed to tide over other crises, including the inspire a lot of youngsters in our country. Hearty Olympics might’ve ended in a blaze of suspension of the country’s president. -

The Private Legal Order of FIFA

Article Between the Green Pitch and the Red Tape: The Private Legal Order of FIFA Suren Gomtsian,t Annemarie Balvert,tt Branislav Hock,t and Oguz Kirman:: INTRODUCTION................ ............................................................. 86 I. THE THEORY OF PRIVATE MODES OF GOVERNANCE .................. .............................. 90 A. Private Ordering by Decentralized Self-Governance ............................. 91 B. Centralized Governance by Private Associations ........ ... ............................... 94 C. Private Governance in the World of Football ....................................... 95 II. ORGANIZATION OF THE WORLD OF FOOTBALL ...................................... 97 A. The Legal Order that FIFA Built: Privately-Designed Rules of Cooperation......................97 B. FIFA 's Private Dispute Resolution System ................................. ....................... 103 C. The Ties that Bind: The System of Sanctions and Incentives Promoting Compliance with the Decisions of the Private Dispute Resolution Bodies..........................................105 III. THE PARALLEL WORLD OF PUBLIC LAW AND THE MECHANISMS OF LOCKING IN FIFA'S PRIVATE LEGAL ORDER................................................. ......... 110 A. Challenges to the Private Legal Order from Public Law .................. ................ 110 1. Employment Laws and FIFA's Transfer Regulations ............... ............. 110 2. Competition Laws and the Monopoly of FIFA ..... ... ........................... 113 t Lecturer in Business Law, Centre -

Futera World Football Online 2010 (Series 2) Checklist

www.soccercardindex.com Futera World Football Online 2010 (series 2) checklist GOALKEEPERS 467 Khalid Boulahrouz 538 Martin Stranzl 606 Edison Méndez 674 Nihat Kahveci B R 468 Wilfred Bouma 539 Marcus Tulio Tanaka 607 John Obi Mikel 675 Salomon Kalou 401 René Adler 469 Gary Caldwell 540 Vasilis Torosidis 608 Zvjezdan Misimovic 676 Robbie Keane 402 Marco Amelia 470 Joan Capdevila 541 Tomas Ujfalusi 609 Teko Modise 677 Seol Ki-Hyeon 403 Stephan Andersen 471 Servet Çetin 542 Marcin Wasilewski 610 Luka Modric 678 Bojan Krkic 404 Árni Arason 472 Steve Cherundolo 543 Du Wei 611 João Moutinho 679 Gao Lin 405 Diego Benaglio 473 Gaël Clichy 544 Luke Wilkshire 612 Kim Nam-Il 680 Younis Mahmoud 406 Claudio Bravo 474 James Collins 545 Sun Xiang 613 Nani 681 Benni McCarthy 407 Fabian Carini 475 Vedran Corluka 546 Cao Yang 614 Samir Nasri 682 Takayuki Morimoto 408 Idriss Carlos Kameni 476 Martin Demichelis 547 Mario Yepes 615 Gonzalo Pineda 683 Adrian Mutu 409 Juan Pablo Carrizo 477 Julio Cesar Dominguez 548 Gokhan Zan 616 Jaroslav Plašil 684 Shinji Okazaki 410 Julio Cesar 478 Jin Kim Dong 549 Cristian Zapata 617 Jan Polak 685 Bernard Parker 411 José Francisco Cevallos 479 Andrea Dossena 550 Marc Zoro 618 Christian Poulsen 686 Roman Pavlyuchenko 412 Konstantinos Chalkias 480 Cha Du-Ri 619 Ivan Rakitic 687 Lukas Podolski 413 Volkan Demirel 481 Richard Dunne MIDFIELDERS 620 Aaron Ramsey 688 Robinho 414 Eduardo 482 Urby Emanuelson B R 621 Bjørn Helge Riise 689 Hugo Rodallega 415 Austin Ejide 483 Giovanny Espinoza 551 Ibrahim Afellay 622 Juan Román Riquelme -

P20 Layout 1

Harrington ends South Africa title drought flatten Ireland WEDNESDAY, MARCH 4, 201517 18 Liverpool look to maintain Champions League charge Page 19 ROME: Roma’s Francesco Totti (second from right) and Juventus’ Vidal (right) run for the ball during their Serie A soccer match. — AP Roma grab point but Juve in control ROME: Seydou Keita cancelled out a superb Carlos Tevez like this means that we are alive,” said the Frenchman after got to but was unable to keep out. glomerate followed by the Slovenia-based Mapi group, free kick as second-placed AS Roma fought back with 10 his team’s sixth successive home league draw. Meanwhile,stricken Parma face yet another week of were shrouded in mystery. men for a fiery 1-1 draw at home to leaders Juventus who Juventus, missing central midfielders Andrea Pirlo and uncertainty with no sign of an end to the financial chaos stayed on course for a fourth successive Serie A title on Paul Pogba through injury, were thoroughly unambitious at the once-proud club where the players have not been ALARM BELLS Monday. and content to sit back and defend for most of the first paid all season and even have to do their own laundry. Italians have been left wondering how one of Europe’s Tevez gave Juventus the lead in the 64th minute, curl- half. The hosts, meanwhile, had drawn six of their seven The Italian Football Federation (FIGC) have called off biggest leagues could allow the situation to reach this ing in a free kick for his 15th league goal of the season, league matches since the Christmas break and their lack Parma’s last two matches but said they would not do that point and said the alarm bells should have rung when and Keita replied 14 minutes later as the teams woke up of confidence was palpable. -

Africa Cup of Nations 2013 Media Guide

Africa Cup of Nations 2013 Media Guide 1 Index The Mascot and the Ball ................................................................................................................ 3 Stadiums ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Is South Africa Ready? ................................................................................................................... 6 History ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Top Scorers .................................................................................................................................. 12 General Statistics ......................................................................................................................... 14 Groups ......................................................................................................................................... 16 South Africa ................................................................................................................................. 17 Angola ......................................................................................................................................... 22 Morocco ...................................................................................................................................... 28 Cape Verde ................................................................................................................................. -

P18 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2014 SPORTS Roma focussed on beating City MILAN: Roma coach Rudi Garcia believes last 16 hopes with a hat-trick in a 3-2 win his side will cope with the pressure of hav- over Bayern last month, will be sorely ing their Champions League destiny in missed by Manuel Pellegrini’s side. their hands today when a win at home over But midfielder James Milner believes Manchester City would ensure they reach City have enough firepower to cause Roma the last 16 for the first time since the problems, and enough experience 2010/11 campaign. throughout the squad to deal with a poten- Roma looked to have taken a huge step tially hostile atmosphere. towards reaching the knockout phase “Sergio is very, very difficult to replace when Francesco Totti scored a 43rd minute but we have a lot of firepower. With the free-kick over another Group E rival CSKA players we do have up there I’m not too Moscow a fortnight ago. worried,” Milner said on Monday. “We will However Roma took their eye off the go there to win. It won’t be easy - Roma are ball in the dying seconds of the match and a good team and I’m sure it will be a great Vasily Berezutsky’s floated cross evaded the atmosphere. entire Roma defence before sneaking “I’ve played in Italy before with City and inside Morgan De Sanctis’s far post. England and you get a hostile atmosphere. The late equaliser was likened to “a You look at the experience we have in this (Mike) Tyson punch” by Totti, who in squad, and that sort of atmosphere won’t Moscow extended his record as the compe- bother anybody.” tition’s oldest scorer at 38 years and 59 If City caught a glimpse of Roma’s last days. -

Here Weren’T Necessarily Any Rules to Stop Independence

The football Pink The Zinedine Zidane Issue 2 I I3 CONTENTS 4 La Castellane: The upbringing that fueled Zidane’s quest for greatness 10 Enzo Francescoli: Zidane’s idol 14 The foreword to a bestselling career: Zidane’s career in French football 20 Post-Platini decline: France, Euro ‘96 and Zidane’s new generation 26 Zinedine Zidane at Juventus: Becoming the King of Italy 34 Zinedine Zidane: “More entertaining than effective” 38 2003: When Zidane and Ronaldo stunned Old Trafford and Zizou’s sole La Liga title win 44 So near and yet so far: “Why do you want to sign Zidane when we have Tim Sherwood?” 48 Zidane’s swansong: The 2006 World Cup 54 Anger management: Balancing the talent with the tantrums The Zinedine Zidane Effect: Turning the Real Madrid embarrassed by Barcelona into 60 European champions I 66 Zinedine Zidane: The third lightning bolt 72 Understanding Zidanology: An inspiration to a generation 4 I I5 La Castellane: The upbringing that fueled Zidane’s quest for greatness 6 7 Today, Zinedine Zidane is footballing royalty Castellane is a concrete maze which may Zidane building’ during and after his time taught it to himself. It is typical of the street but his humble beginnings don’t paint a not necessarily make you fall in love at first living and developing his legendary skills in footballer to be a very good ball-carrier. It picture bearing any semblance of nobility. sight. this community. While that building has now is generally very much a ‘fend for yourself’ I La Castellane is just over 10km north of the been demolished, Zidane’s legacy lives on environment to develop your skills. -

2015/16 UEFA Champions League Technical Report

CONTENTS 4 6 16 22 INTRODUCTION THE ROAD TO THE FINAL THE WINNING SAN SIRO COACH 24 26 34 38 RESULTS TECHNICAL GOALSCORING GOALS OF THE TOPICS ANALYSIS: THE SEASON FINAL SCORE 40 44 46 48 TALKING POINTS ALL-STAR SQUAD STATISTICS: STATISTICS: ATTEMPTS FIGHTING BACK ON GOAL 49 50 52 54 STATISTICS: STATISTICS: STATISTICS: STATISTICS: BORN TO RUN ROUTE TO GOAL POSSESSION CROSSES 55 56 STATISTICS: TEAM PROFILES CORNERS 3 INTRODUCTION OPINION, DISCUSSION GROUP A GROUP B AND DEBATE Paris Real Madrid CF FC Shakhtar Malmö FF PSV Eindhoven Manchester PFC CSKA VfL Wolfsburg UEFA’s team of technical observers met after the final in Milan Saint-Germain (RM) Donetsk (MAL) (PSV) United FC Moskva (WOL) (SHK) (MU) (CSKA) to review the key trends and tactics from another absorbing (PSG) UEFA Champions League campaign GROUP C GROUP D On a warm evening in Milan, Real Madrid CF and the Football Association of Serbia sporting lifted their 11th UEFA Champions League title director Savo Milosević were also present, along after a hard-fought victory over local rivals Club with UEFA Jira Panel members Peter Rudbæk Atlético de Madrid. The teams could not be (Denmark) and Ginés Meléndez (Spain), both separated after 120 minutes and finally it fell to technical directors in their respective countries, Cristiano Ronaldo to fire the winning penalty and Jean-Paul Brigger, FIFA’s technical study SL Benfica Club Atlético Galatasaray AŞ FC Astana Juventus Manchester Sevilla FC VfL Borussia past Jan Oblak and seal victory for Zinédine group chief. Additional technical observers were (BEN) de Madrid (GAL) (AST) (JUV) City FC (SEV) Mönchengladbach Zidane’s side. -

Seydou Keïta CV

Seydou Keïta Seydou Keïta, Untitled (Fleur De Paris), 1959. Gelatin Silver Print, 24 x 18 cm. Seydou Keïta (1921-2001) was a Malian studio photographer whose photographs eloquently portray Bamako society during its era of transition from a cosmopolitan French colony to an independent capital. Initially trained by his father to be a carpenter, Keïta’s career as a photographer was launched in 1935 by an uncle who gave him his first camera, a Kodak Brownie Flash, which he had purchased during a trip to Senegal. During his adolescence, Keïta mastered the technical challenges of shooting and printing; he later purchased a large-format camera. The larger format not only offered an exceptional degree of resolution, it also made it possible for Keïta to make high quality contact prints without the aid of an enlarger. In 1948, he opened his own studio in Bamako and quickly built up a successful business. Seydou Keïta, Untitled (Portrait), 1949. Gelatin Silver Print, 50 x 60 cm. Whether photographing single individuals, families or professional associations, Keïta balanced a strict sense of formality with a remarkable level of intimacy with his subjects. Like many professional photographers, he furnished his studio with numerous props, from backdrops and costumes, to Vespas and luxury cars. He would renew these props every few years, which later allowed him to establish a chronology for his work. Keïta commented on his studio practice, “It’s easy to take a photo, but what really made a difference was that I always knew how to find the right position, and I was never wrong.