Introduction: Historical Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publications of Interest

PUBLICATIONS OF INTEREST Compiled by Beryl M. Benjers, Ph.D. Technical Information Specialist This list of references offers Journal readers significant information on the availability of recent rehabilitation literature in various scientific, engineering, and clinical fields. The Journal provides this service in an effort to fill the need for a comprehensive and interdisciplinary indexing source for rehabilitation literature. A listing of the periodicals reported on follows the references. To obtain reprints of a particular article or report, direct your request to the appropriate contact source listed in each citation. Assessment of a New Hip Dynamometer. Green J, McKenna F, Ellis M, Helliwell P, Howe A, Cham- Adapting Personal Computers for Use by High- berlain MA, Eng Med 16(4):213-216, 1987. Level Quadriplegics. Kilgallon MJ, Roberts DP, (CONTACT: J. Green, The Rheumatism and Reha- Miller S, Med Instrumen 21(2):97-102, 1987. bilitation Research Unit, University of Leeds, Leeds, (CONTACT: Michael Kilgallon, Physical Sciences England) Dept., Calspan Corp., PO Box 400, Buffalo, NY 14225) Automatic Grasping: An Optimization Approach. Jameson JW, Leifer LJ, IEEE Trans Syst Man Advances in the Fracture Mechanics of Cortical Cybern 17(5):806-814, 1987. Bone. Bonfield W, J Biomech 20(11/12): 1071-1081, (CONTACT: Larry J. Leifer, Stanford University 1987. Mechanical Engineering Dept., Stanford, CA 94305) (CONTACT: W. Bonfield, Dept. of Materials, Behavior of an External Fixation Frame Incorporat- Queen Mary College, London, El 4NS, UK) ing an Angular Separation of the Fixator Pins. Egan JM, Shearer JR, Clin Orthop 223:265-274, 1987. Analysis of the Asymmetrically Loaded Spine by (CONTACT: Dr. -

Echoes in the Halls

An Unofficial History of the University of Alberta ASSOCIATION OF PROFESSORS EMERITI OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from University of Alberta Libraries https://archive.org/details/echoesinhallsunoOOmcin An Unofficial History of the University of Alberta ASSOCIATION OF PROFESSORS EMERITI OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA □OA LES EDITIONS DUVAL The University of Alberta Press Published jointly by Duval House Publishing 18120 - 102 Avenue Edmonton, Alberta T5S 1S7 Telephone: (780) 488-1390 Fax: (780) 482-7213 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.duvalhouse.com University of Alberta Press □OA Ring House 2 Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E2 Telephone: (780) 455-2200 Duval House Publishing and the University of Alberta Press gratefully Canada ac^now^e(^^e financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities. © 1999 Association of Professors Emeriti of the University of Alberta All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic or mechanical—without prior written permission from the publishers. Printed in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Echoes in the halls ISBN 1-55220-074-4 1. University of Alberta-History-Anecdotes. I. Spencer, Mary, 1923- II. Dier, Kay, 1922- III. McIntosh, Gordon. LE3.A619E33 1999 378.7123’3 C99-911163-9 Cover photos: Front: Dr. Mark Arnfield adjusting the Argon-driven dye laser with the -

Creating the Future of Health: the History of the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary, 1967-2012

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2021-02 Creating the Future of Health: The History of the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary, 1967-2012 Lampard, Robert; Hogan, David B.; Stahnisch, Frank W.; Wright Jr., James R. University of Calgary Press Lampard, R., Hogan, D. B., Stahnisch, F. W., & Wright Jr, J. R. (2021). Creating the Future of Health: The History of the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary, 1967-2012. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/113308 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca CREATING THE FUTURE OF HEALTH: Creating the The History of the Cumming School of Medicine Future of Health The History of the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary, 1967–2012 at the University of Calgary, 1967–2012 Robert Lampard, David B. Hogan, Frank W. Stahnisch, and James R. Wright, Jr. ISBN 978-1-77385-165-5 Robert Lampard, David B. Hogan, Frank W. Stahnisch, and James R. Wright, Jr. THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. -

Thursday, May 17, 2012 Oral Presentations Classroom D 2F1.04 Walter Mackenzie Centre Poster Presentations Lower Level John W Scott Health Sciences Library

GRADUATE STUDENTS | RESIDENTS | POSTDOCTORAL FELLOWS THURSDAY, MAY 17, 2012 ORAL PRESENTATIONS CLASSROOM D 2F1.04 WALTER MACKENZIE CENTRE POSTER PRESENTATIONS LOWER LEVEL JOHN W SCOTT HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARY 1 Chair’s Welcome Barbara J. Ballermann, MD “Welcome to our Research Day - one of the most important and rewarding days in our academic year! It is a day when we hear about the exciting research projects in which our Graduate Students, Post Doctoral Fellows, Core Internal Medicine and Subspecialty Residents are involved. This year we are fortunate to have as our guest oral adjudicator, Dr. Gary Curhan, Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology, Harvard School of Medicine. Research Day gives the opportunity for all Department members and guests to interact with our young researchers. We currently have a total of 60 Graduate Students, 34 Postdoctoral Fellows and 175 Core Internal Medicine and Subspecialty Residents. As such, I would encourage you to attend the oral presentations in Classroom D and visit at least three posters which will be located in the lower level of the John W Scott Library. Enjoy today and be sure to join us for the presentation of awards at the conclusion of the afternoon oral presentations.” 2 EVANGELOS MICHELAKIS, MD, ASSOCIATE CHAIR, RESEARCH “During the second Persian invasion to Greece (September of 480 BC) a critical battle took place in Thermopylae (“Hot Gates”) a narrow coastal passage in central Greece. The Greek army, under the Spartan King Leonidas, of about 7000 men was called to fight the Persian army, under King Xerxes, of more than 500,000. After the second day of battle, a local resident named Ephialtes betrayed the Greeks by revealing a small path that led behind the Greek lines. -

2005-2006, Rich with Accomplishments and Change

DEPARTMENT of SURGERY Department of Surgery Annual Report July 1, 2005 - June 30, 2006 R.S. McLaughlin Professor and Chair Dr. R. K. Reznick Associate Chair and Vice-Chairs Dr. B.R. Taylor - Associate Chair Dr. J.A. Bohnen - Vice-Chair, Education Dr. R. Richards - Vice Chair, Clinical Dr. B. Alman - Vice-Chair, Research Surgeons-in-Chief Dr. J. Wright - The Hospital for Sick Children Dr. Z. Cohen - Mount Sinai Hospital Dr. L. Smith - St. Joseph’s Health Centre Dr. O. Rotstein - St. Michael’s Hospital Dr. R. Richards - Sunnybrook & Women’s College Health Sciences Centre Dr. L. Tate - Toronto East General Hospital Dr. B.R. Taylor - University Health Network University Division Chairs Dr. M. Wiley - Anatomy Dr. R. Weisel - Cardiac Surgery Dr. Z. Cohen - General Surgery - Bernard and Ryna Langer Chair Dr. J. Rutka - Leslie Dan Professor and Chair of Neurosurgery Dr. J. Waddell - A.J. Latner Professor and Chair of Orthopaedic Surgery Dr. P. Neligan - Wharton Chair in Reconstructive Plastic Surgery Dr. S. Keshavjee - Thoracic Surgery Dr. S. Herschorn - Urology Dr. T. Lindsay - Vascular Surgery TABLE of CONTENTS Report from the Chair ...................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Undergraduate Education ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Postgraduate Education .................................................................................................................................................................. -

MEDICINE at the UNIVERSITY of ALBERTA Published by the Department of Medicine, University of Alberta · Edmonton, AB T6G 2B7

THE HISTORY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA Published by the Department of Medicine, University of Alberta · Edmonton, AB T6G 2B7. Printed by Friesens, Altona, Manitoba. Printed in Canada. Edited by Dawna Gilchrist, MD. Design by Carol Dragich, Dragich Design. CONTENTS 5 Editor's Foreword 7 NOTES FROM THE CHAIR 9 The Early Years various sources 11 1944-1954 John W. Scott 17 1954-1969 Donald R. Wilson 23 1969-1974 Robert S. Fraser 33 1975-1986 George D. Molnar 41 1986-1990 E. Gamer King 44 The Interregnums Dawna M. Gilchrist 45 1993-1999 Paul W. Armstrong 53 1999-2004 Thomas J. Morrie 59 THE DIVISIONS 61 Cardiology Richard Rossa/I 65 Clinical Hematology and Medical Oncology Robert Turner 69 Dermatology Gilles Lauzon 73 Endocrinology and Metabolism Peter Crockford 78 Gastroenterology Richard Sherbaniuk 81 General Internal Medicine Lee Anhalt 85 Geriatric Medicine Peter McCracken 89 Infectious Diseases George Goldsand 94 Medical Oncology Anthony Fields 98 Nephrology and Immunology Ray Ulan 102 Neurology Fred Wilson & Harold Jacobs 105 Pulmonary Medicine Brian Sproule 109 Rheumatology Anthony Russell 3 111 SPECIAL TOP I CS 113 Medicine Overview Allan M. Edwards 117 Medical Education }. Alan Gilbert 121 Residency Training Richard Rossa/I 123 Transplantation Philip Halloran 125 Poliomyelitis Brian Sproule 130 Tuberculosis Anne Fanning 134 Diabetes Edmond Ryan 13 7 THE THREE ENGLISHMEN 139 John R. Dossetor 145 George Monckton 152 Richard Rossall 159 APPENDIX 161 Chairs of the Department of Medicine 161 Divisional Directors 163 Department Members 1999-2004, GFT 172 Department Members 1999-2004, Adjunct, Emeritus and Clinical 175 Photographs 4 EDITOR'S FOREWORD In 2002, Dr. -

Anaesthesia in the Atlantic Provinces

THE NOVA SCOTIA MEDICAL BULLETIN Editor-in-Ch ief Editorial Board Manaqinq Editor DR. lA~ E. PURKIS DR. c. J. w. BECKWITH Board Corresponding Members Departments D R. I. D. ~1AXWELL Secretaries of Branch Societies ~Iedico-Legal Column D R. D. A. E. SIIEPUARO DR. I. D. ~IAX WELL D R. W. E. P oLLETT Ad vertising D R .\. J. B o oR DR. D. A. E. SHEPHARO T his issue contains a Symposium on Anaesthesia based on papers presented at t he Atlantic Regional Meetin g of the Canadian Anaesthetists' Society, St . J oh n 's, Newfoundland, September 1967. Coordinating Editor: Dr. David Shephard Anaesthesia in the Atlantic Provinces c. 1:. HuoEnsox. ~ID. c:.r. CRCP(C). FACA* St. J ohn"s, Newfoundland The pre entation of this ymposium by anaes .\dvances in medical cience are progre sing at thetists or the Atlantic Province is in itseif signifi such a rapid rate that within the past twenty years can t. It points to the increasingly important role there has been an almost complete change in the ~· hi ch the specialty and its practitioners are playing practice of anae thesia and doctors practi ing in m the medical and urgieal care of patients in thi this field need constant refreshment and renewal. part of the world. The regular attendance at regional and national meetings cannot help but make one appreciate the Tht subjects co,·ered in thi ympo ium are largely nature and rapidity of these changes. For many tho t' presented at the Annual Regional ~ Ieeting of years anaesthe ia was limited to the subduing of the Canadian Anaeslhetists· ociety of the Atlantic patients for surgical inten·entions and very little, Provinces held in t. -

Annual 2019 2020 Report You Are Making a Difference Of

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 2020 YOU ARE MAKING A DIFFERENCE OF A LIFETIME CONTENTS Message from Our Fundraising Leadership & Excellence 03 President & CEO 09 Events 24 in Philanthropy Message from Strategic 2019 – 2020 04 Our Board Chair 12 Partnerships 25 Financial Highlights Major Generosity Canada’s First 06 Investments 13 in Action 35 Stroke Ambulance s I write this message to you, I am struck by how much our world has changed in the past year. We are all experiencing COVID-19, the pandemic that has significantly impacted all of us. AI hope and pray that you and your loved ones are staying safe, and that those of you who need help get it as quickly as possible. We have also experienced changes here, at the MESSAGE University of Alberta Hospital, and, even closer to home, at the University Hospital Foundation. Thank you to each and every one of you who contributed FROM to the Brain Centre Campaign. The campaign wrapped up last September after raising an incredible $70 million, changing brain care dramatically for thousands of Albertans OUR and western Canadians. The researchers that your generosity supports – such as Dr. Glen Jickling who is moving closer and closer to developing a blood test that will diagnose a stroke within PRESIDENT minutes, and Dr. Jack Jhamandas, whose research in Alzheimer’s disease may one day restore the memory in patients living with that terrible condition – stand to transform & CEO brain care for millions around the world. Your donations supported a $10 million gift to the Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute in celebration of its tenth anniversary. -

Eponyms in Dermatology Literature Linked to Canada

Dermatology Eponyms DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20131.29 EPONYMS IN DERMATOLOGY LITERATURE LINKED TO CANADA Khalid Al Aboud1, Ahmad Al Aboud2 1Dermatology Department, King Faisal Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia Source of Support: 2Dermatology Department, King Abdullah Medical City, Makkah, Saudi Arabia Nil Competing Interests: None Corresponding author: Dr. Khalid Al Aboud [email protected] Our Dermatol Online. 2013; 4(1): 113-116 Date of submission: 20.09.2012 / acceptance: 12.11.2012 Cite this article: Khalid Al Aboud, Ahmad Al Aboud: Eponyms in dermatology literature linked to Canada. Our Dermatol Online. 2013; 4(1): 113-116 Canada is a North American country with a population of and The Canadian Dermatology Nurses Association was approximately 33.4 million as of 2011. Per capita income is founded on 1997. the world’s ninth highest, and Canada ranks sixth globally in As a testimony of its Excellency in dermatology teaching, human development [1]. there are several specialized fellowships in Canada, in There are several eponyms in dermatology which are linked different subspecialties of dermatology. These fellowships to Canada. In Table I [2-11], we listed selected eponyms in accept candidates from all over the world. dermatology literature which are linked to Canada. There are also important educational resources in Numerous activities related to dermatology have occurred dermatology which are based in Canada. Just an example is, in Canada. The Canadian Dermatology Association, which Dermanities (www.dermanities.com), which was launched in published the well-known periodical, The Journal of 2002 by Benjamin Barankin and David J. Elpern. Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery, was founded in 1925. -

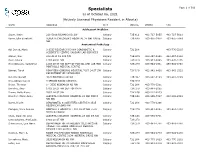

Specialists Page 1 of 509 As of October 06, 2021 (Actively Licensed Physicians Resident in Alberta)

Specialists Page 1 of 509 as of October 06, 2021 (Actively Licensed Physicians Resident in Alberta) NAME ADDRESS CITY POSTAL PHONE FAX Adolescent Medicine Soper, Katie 220-5010 RICHARD RD SW Calgary T3E 6L1 403-727-5055 403-727-5011 Vyver, Ellie Elizabeth ALBERTA CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL 28 OKI DRIVE Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-2978 403-955-7649 NW Anatomical Pathology Abi Daoud, Marie 9-3535 RESEARCH RD NW DIAGNOSTIC & Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3295 SCIENTIFIC CENTRE CALGARY LAB SERVICES Alanen, Ken 242-4411 16 AVE NW Calgary T3B 0M3 403-457-1900 403-457-1904 Auer, Iwona 1403 29 ST NW Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-8225 403-270-4135 Benediktsson, Hallgrimur 1403 29 ST NW DEPT OF PATHOL AND LAB MED Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-1981 493-944-4748 FOOTHILLS MEDICAL CENTRE Bismar, Tarek ROKYVIEW GENERAL HOSPITAL 7007 14 ST SW Calgary T2V 1P9 403-943-8430 403-943-3333 DEPARTMENT OF PATHOLOGY Bol, Eric Gerald 4070 BOWNESS RD NW Calgary T3B 3R7 403-297-8123 403-297-3429 Box, Adrian Harold 3 SPRING RIDGE ESTATES Calgary T3Z 3M8 Brenn, Thomas 9 - 3535 RESEARCH RD NW Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3201 Bromley, Amy 1403 29 ST NW DEPT OF PATH Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-5055 Brown, Holly Alexis 7007 14 ST SW Calgary T2V 1P9 403-212-8223 Brundler, Marie-Anne ALBERTA CHILDREN HOSPITAL 28 OKI DRIVE Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-7387 403-955-2321 NW NW Bures, Nicole DIAGNOSTIC & SCIENTIFIC CENTRE 9 3535 Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3206 RESEARCH ROAD NW Caragea, Mara Andrea FOOTHILLS HOSPITAL 1403 29 ST NW 7576 Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-6685 403-944-4748 MCCAIG TOWER Chan, Elaine So Ling ALBERTA CHILDREN HOSPITAL 28 OKI DR NW Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-7761 Cota Schwarz, Ana Lucia 1403 29 ST NW Calgary T2N 2T9 DiFrancesco, Lisa Marie DEPARTMENT OF PATHOLOGY (CLS) MCCAIG Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-4756 403-944-4748 TOWER 7TH FLOOR FOOTHILLS MEDICAL CENTRE 1403 29TH ST NW Duggan, Maire A. -

Echoes in the Halls : an Unofficial History of the University of Alberta

An Unofficial History of the University of Alberta ASSOCIATION OF PROFESSORS EMERITI OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA An Unofficial History of the University of Alberta ASSOCIATION OF PROFESSORS EMERITI OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA □OA LES EDITIONS DUVAL The University of Alberta Press Published jointly by Duval House Publishing 18120 - 102 Avenue Edmonton, Alberta T5S 1S7 Telephone: (780) 488-1390 Fax: (780) 482-7213 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.duvalhouse.com University of Alberta Press □OA Ring House 2 Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E2 Telephone: (780) 455-2200 Duval House Publishing and the University of Alberta Press gratefully Canada ac^now^e(^^e financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities. © 1999 Association of Professors Emeriti of the University of Alberta All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic or mechanical—without prior written permission from the publishers. Printed in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Echoes in the halls ISBN 1-55220-074-4 1. University of Alberta-History-Anecdotes. I. Spencer, Mary, 1923- II. Dier, Kay, 1922- III. McIntosh, Gordon. LE3.A619E33 1999 378.7123’3 C99-911163-9 Cover photos: Front: Dr. Mark Arnfield adjusting the Argon-driven dye laser with the sixteen fibreoptic cables for interstitially applied PDT in Dunning R3327 rat prostate cancers (photo courtesy of Malcolm McPhee) Back: The trunk -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT YOU MAKE THINGS HAPPEN CONTENTS Message from our Board Chair Major Investments Fundraising Events Festival of Trees Full House Lottery and Strategic Partnerships Donors Gifts in Memory Brain Campaign Donors Financial Statements Planned Giving GiveToUHF.ca 3 our gifts to the University Hospital Foundation write someone else’s story. A story of a life-saving heart MESSAGE surgery, a story of gratitude for prostate cancer care, a story of being cured of debilitating migraines because of Gamma FROM Knife radiosurgery. And behind your gifts are thousands of deeply personal stories that motivated grateful patients, thankful families and supportive businesses to give back — and help push the OUR BOARD boundaries of care and research at the University of Alberta Hospital, the Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute and the Kaye Edmonton Clinic. CHAIR So many innovative developments in the medical field happening right now are only happening because of the generous support from you, our donors. Through your generosity, we can do so much more to advance care, and drive research and advancement. The inaugural issue of HERE magazine, which you received along with your copy of the Annual Report, celebrates innovations, successes and Dan Hanna Cathy Osborne President, Parkwood Master Builder Senior Operating Officer, University Of Alberta Hospital, Dr. Shelley Scott Terry Freeman, FCPA, FCA, ICD.D Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute, Community Volunteer Head of Investments, ATB Capital Kaye Edmonton Clinic Robert Bessette, FMA, ICD.D Jim Allen Joyce Mallman Law Barry James, Past Chair CEO, Jatec Electric Ltd. President, FCPA, FCA, ICD.D Vice President & University Hospital Foundation Chief Corporate Development Officer, Associate Portfolio Manager, Joette Decore Lloyd Sadd Insurance Brokers Bessette Wealth Management, Executive Vice President, RBC Dominion Securities Inc.