Appropriation of Privacy Management Within Social Networking Sites Catherine Dwyer New Jersey Institute of Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeless and Self Organization

Anthropology News, vol. 55, 2014, pp. 1-18. HOMELESS AND SELF ORGANIZATION. Ana Inés Heras. Cita: Ana Inés Heras (2014). HOMELESS AND SELF ORGANIZATION. Anthropology News, 55 1-18. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/ana.ines.heras/337 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons. Para ver una copia de esta licencia, visite https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.es. Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. Published bimonthly by the American Anthropological Association Volume56•Issue1–2 JANUARY/FEBRUARY2015 INSIDE THE NEWS Ferguson: An American Story Ferguson and the Right to Black Life Standing Their Ground in #Ferguson Raymond Codrington Steven Gregory Lydia Brassard and Michael Partis The Violence of the Status Quo: Beheaded: An Anthropology Dealing with Reality: Michael Brown, Ferguson and Tanks Christian S Hammons Sexual Harassment in the Field Pem Davidson Buck Beatriz Reyes-Foster and Ty Matejowsky Inside Anthropology News INFOCUS R A | The Violence of the Status Quo: Michael Brown, Ferguson and Tanks ........................................................................................................................ 4 R A | Ferguson and the Right to Black Life .................................................. 5 R -

I V Public Childhoods: Street Labor, Family, and the Politics of Progress

Public Childhoods: Street Labor, Family, and the Politics of Progress in Peru by Leigh M. Campoamor Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Diane Nelson ___________________________ Irene Silverblatt ___________________________ Rebecca Stein ___________________________ Elizabeth Chin Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 i v ABSTRACT Public Childhoods: Street Labor, Family, and the Politics of Progress in Peru by Leigh M. Campoamor Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Diane Nelson ___________________________ Irene Silverblatt ___________________________ Rebecca Stein ___________________________ Elizabeth Chin An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 Copyright by Leigh M. Campoamor 2012 Abstract This dissertation focuses on the experiences of children who work the streets of Lima primarily as jugglers, musicians, and candy vendors. I explore how children’s everyday lives are marked not only by the hardships typically associated with poverty, but also by their -

A Community's Cook Retiring

INSIDE THIS EDITION COMET SPORTS $1.00 Lost tortoise finds Comet graduate Vol. 62, Issue 43 1section • 14 pages its wayhome picks fantasyteam Not over 75% advertising www.braidwoodjournal.com WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2020 | A FREE PRESS NEWSPAPER Indoor dining at bars, restaurants to close in Will County Region 7 hits grants from the Illinois Department increases, hitting 8.2% on Oct. 15, Public health officials are observ- of Commerce and Economic “WE’RE GOING TO SEE THE 8.3% on Oct. 16, and 8.6% on Oct. 17. ing businesses blatantly disregarding three days of Opportunity. By county, Will County saw its mitigation measures, people not Pritzker said on Tuesday after- RIPPLING EFFECTS OF THESE three day average rise to 8.4% on Oct.. social distancing, gathering in large positivity above 8% noon that positive cases were trend- TRENDS.” 15, 8.5% on Oct. 16, and 8.9% on Oct. groups, and not using face coverings. ing upward across the state. State offi- 17. In Kankakee County, the average Mayors, local law enforcement, STAFF REPORT cials said that Illinois was officially in was 7.2%, 7%, and 7.3% on those state’s attorneys, and other commu- the second wave of the virus. JB PRITZKER same days, respectively. nity leaders can be influential in GOVERNOR Bars and restaurants in Will “We’re going to see the rippling Region 7 also had six days of hos- ensuring citizens and businesses fol- County will have to shutter their effects of these trends,” Pritzker said pital admission increases. low best practices. indoor dining services once again at as cold weather approaches. -

THE TUFTS DAILY NEWS | FEATURES Wednesday, November 30, 2005

THE TUFTS Where You Read It First VOLUME L, NUMBER 55 DAILY WEDNESDAY,NOVEMBER 30, 2005 Oh, the places they will go: ROTC seniors get placements BY BRIAN MCPARTLAND Officer Qualifying Test, similar to the SAT Senior Staff Writer but with added sections for pilot and navi- gator topics. The test includes questions on As some seniors go to career fairs for spatial reasoning and asks students to draw finance and others go to fairs for communi- maps. cations, one group of students is headed Dixon took the test in February of her someplace else entirely after graduation: the sophomore year and applied for the pilot U.S. Armed Forces. and navigator programs. Her score qualified In the past couple of weeks, students in her to become a navigator, an eight-year the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) commitment. program have begun to receive their post- She applied for a position in personnel, graduation assignments. though, and received her first choice last Senior Caroline Kennedy will be going April. She was also assigned her third choice into military intelligence in the Army — her location, RAF Mildenhall which is 70 miles first choice. ROTC participants send their outside of London. “I specified that I wanted choices and applications to ROTC head- to be assigned to a base overseas,” she said. quarters for their branch of the military: Dixon applied for a postponement of her Army, Navy or Air Force. Marine Corps stu- active duty to attend graduate school in dents go through the Navy ROTC. community health, and she said she will Kennedy will spend 18 weeks in Ft. -

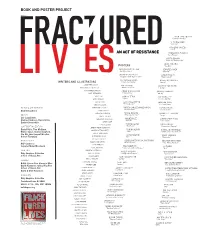

Book and Poster Project an Act of Resistance

BOOK AND POSTER PROJECT IGOR LANGSHTEYN “Secret Formulas” SEYOUNG PARK “Hard Hat” CAROLINA CAICEDO “Shell” AN ACT OF RESISTANCE FRANCESCA TODISCO “Up in Flames” CURTIS BROWN “Not in my Fracking City” WOW JUN CHOI POSTERS “Cracking” SAM VAN DEN TILLAAR JENNIFER CHEN “Fracktured Lives” “Dripping” ANDREW CASTRUCCI LINA FORSETH “Diagram: Rude Algae of Time” “Water Faucet” ALEXANDRA ROJAS NICHOLAS PRINCIPE WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS “Protect Your Mother” “Money” SARAH FERGUSON HYE OK ROW ANDREW CASTRUCCI ANN-SARGENT WOOSTER “Water Life Blood” “F-Bomb” KATHARINE DAWSON ANDREW CASTRUCCI MICHAEL HAFFELY MIKE BERNHARD “Empire State” “Liberty” YOKO ONO CAMILO TENSI JUN YOUNG LEE SEAN LENNON “Pipes” “No Fracking Way” AKIRA OHISO IGOR LANGSHTEYN MORGAN SOBEL “7 Deadly Sins” CRAIG STEVENS “Scull and Bones” EDITOR & ART DIRECTOR MARIANNE SOISALO KAREN CANALES MALDONADO JAYPON CHUNG “Bottled Water” Andrew Castrucci TONY PINOTTI “Life Fracktured” CARLO MCCORMICK MARIO NEGRINI GABRIELLE LARRORY DESIGN “This Land is Ours” “Drops” CAROL FRENCH Igor Langshteyn, TERESA WINCHESTER ANDREW LEE CHRISTOPHER FOXX Andrew Castrucci, Daniel Velle, “Drill Bit” “The Thinker” Daniel Giovanniello GERRI KANE TOM MCGLYNN TOM MCGLYNN KHI JOHNSON CONTRIBUTING EDITORS “Red Earth” “Government Warning” JEREMY WEIR ALDERSON Daniel Velle, Tom McGlynn, SANDRA STEINGRABER TOM MCGLYNN DANIEL GIOVANNIELLO Walter Sipser, Dennis Crawford, “Mob” “Make Sure to Put One On” ANTON VAN DALEN Jim Wu, Ann-Sargent Wooster, SOFIA NEGRINI ALEXANDRA ROJAS DAVID SANDLIN Robert Flemming “No” “Frackicide” -

Designing Privacy Into Online Communities

Dwyer and Hiltz Designing Privacy Into Online Communities Designing Privacy Into Online Communities Catherine Dwyer Starr Roxanne Hiltz Pace University New Jersey Institute of Technology [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Participation has exploded in online communities such as social networking sites, media sharing sites, and blogging sites. This widespread participation has generated substantial concern about the privacy implications of use. Although most online communities include privacy management features, it is not well understood how members of online communities take advantage of privacy management. To explore this issue, a study was conducted that compared privacy management on Facebook and MySpace, two popular social networking sites. Out of 222 subjects, 18.9% or nearly one in five had suffered a privacy incident within the past year. In a particularly striking result, less than half of those who suffered a privacy incident either reviewed or changed their privacy settings. So even though privacy incidents occur regularly, these findings indicate privacy management tools are not extensively used to protect privacy. This provides evidence of poor design of privacy management on social networking sites. To improve design, we argue that privacy must be conceptualized as a quality of an online space, rather than as a collection of access settings to be managed by individual members. This moves privacy from an individual consideration to the level of a structural component of a system. We offer an analysis of current privacy management practices and offer suggestions for improving the design of privacy management in social software. Keywords Online privacy management, social software, system design INTRODUCTION Social networking sites have grown to be the most popular type of computer-mediated communication system to support online communities. -

Historical Museum Reopens

PRSRT-STD SPORTS: Postal Customer U.S. Postage South Lake tops Clermont, FL Paid 34711 Clermont, FL Leesburg, 28-24 Permit #280 SEE PAGE B4 REMEMBER WHEN | B1 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2013 www.southlakepress.com 50¢ NEWSTAND TAVARES GROVELAND Historical Museum reopens Bottler asked ROXANNE BROWN | Staff Writer [email protected] to justify fter months of turmoil that ended earlier this year with A the election of a new board request to of directors, the Lake Coun- ty Historical Society is back on track and has reopened the Lake double usage County Historical Museum. It recently took about 18 vol- Staff Report unteers 140 hours each to move the museum’s collection from Niagara Bottling in has until February the first floor to the fifth floor of to justify its request to the St. Johns River the Lake County Historic Court- Water Management District to nearly dou- house on Main Street in Tavares. ble the amount of water it pumps from the “It was a Herculean job but we Floridan aquifer. did it. It was a big accomplish- District staff said additional technical in- ment for us,” Historical Society formation was needed on the company’s ap- President Rick Reed said. plication and last week sent out a Request for Earlier this year, the Historical Additional Information (RAI) letter. Society was hampered by infight- Niagara has until Feb. 7 to respond to ing that divided the group and saw both sides recognizing their the RAI or to request an extension to the own board members following SEE NIAGARA | A2 separate elections. -

New Paltztimes Imes

Special section Halloween Sports Tribute Healthy Hudson Valley: Where to celebrate OCIAA swimming Longtime Mohonk Mountain Healthy Body & Mind Halloween locally championships House head Bert Smiley dies at 74 INSIDE 4 15 8 THURSDAY, OCT. 25, 2018 $1.50 VOL. 18, ISSUE 43 New Paltz Timimeses www.hudsonvalleyone.com NEWS OF NEW PALTZ, GARDINER, HIGHLAND, ROSENDALE & BEYOND High rise Flag central Supervisor Bettez says the New Paltz New Paltz American fl ag appreciation event draws support, protest town budget is “not pretty” by Terence P Ward EW PALTZ TOWN Supervisor Neil Bettez explained dur- ing the discussion of the 2019 N budget at the October 18 Town Board meeting that the only way the in- crease will be within the tax cap would be with layoff s. Otherwise, contracted pay raises and health-insurance cost hikes together eat up more than the cap, which this year is actually two percent. The tentative budget, fi led Septem- ber 30, shows expenses of $11,872,921, of which $9,898,272 would be raised through taxes. The tax levy of the ap- proved 2018 budget is $8,348,108. Cuts identifi ed by Bettez and comptrol- ler Jean Gallucci bring the increase down to 8.9% from the 17.5% in the “wish-list” round. The tax cap would limit increases to $176,000, which Gallucci called “im- possible,” as fi xed expenses alone will rise $234,000. That includes $40,000 for workers’ compensation and $67,000 in police pay increases agreed to in a past multi-year contract which current council members are bound to honor. -

Via`A Via`A Via`A

VI NER I OMÂN ia NUL XX I R P A G I N I LEGE T V E I R , A , N . 6326 20 + A , 1,2 L - Duminică Sâmbătă 7 - 8 august 2010 UGUST - 6 A 2010 - - Pl e d o a r i e miley a împlinit de curând 27 de ani. Nu a organizat ni cio petrecere de ziua lui pentru că a vrut să se relaxe pentru limba ze și să se odihnească. Și avea și motive să își dorească - română(IX) odihnă, mai ales că artistul a fost de acord să se alătu Meci tare cu Rapidul, Sre celei mai îndrăzneţe campanii de voluntariat din România Neologisme „Let`s Do It, România!” şi nu numai Let`s Do It, România!” este un proiect ambiţios care își pro Idei pune să cureţe întreaga ţară de gunoaie într-o singura zi. Prima N FIECARE S ă P T ă M Â N ă vedeta care s-a alăturat cauzei proiectului este Smiley, care a - filmat și un testimonial prin care susţine ideea. pag. 4 Muzicianul e sută la sută de acord cu această iniţiativă - și e decis să se apuce de strâns peturi, hârtii, ambalaje și mucuri de ţigară. În săptămânile care vor urma, echi Constatări în faţa pa ”Let`s Do It, România!” va prezenta clipuri cu diverse micului ecran vedete, din diferite zone de interes, care vor îndemna pu blicul să se înscrie pentru Ziua de Curăţenie Naţională din Gigolo şi damă 25 septembrie. gratuit diseară, de la ora 20.00 La acea dată toţi românii interesaţi de ţara lor se de partid unesc pentru o cauză comună: curăţarea României de Idei gunoaie. -

Friday, August 31. 2007 Volume 134, Issue 1 - -- __ ...___ --~------~~- 2 August 31, 2007

Friday, August 31. 2007 Volume 134, Issue 1 - -- __ _... ___ _ --~------~~- 2 August 31, 2007 2 News 6 Editorial 7 Opinion 13 Mosaic ... 19 Classifieds 20 Sports THE REVIEW /Ricky Berl Vandals get creative with their damage to Main Street property~ JrV<~l> excJJJsives Check out these articles and more on udreview.com • Delaware cracks down on its prostitution problem • College of Arts and Sciences remembers dean's legacy THE REVIEW/Ricky Berl THE REVIEW/Ricky Berl The CosmoGirl Sound Stage Tour came to the Students prove there is always time for the role-playing North Green on Aug. 27. game Dagorhir on campus. The Review is published once weekly every Tuesday of the school year, Editor In Chief Administrative News Editor Managing Sports Editors except during Winter and Summer Sessions. Our main office is located at 250 Wesley Case Jessica Lapointe Kevin Mackiewicz, Mike LoRe Perkins Student Center, Newark, DE 19716. If you have questions about advertising Executive Editor City News Editor Sports Editors Sarah Lipman Katie Rogers Matthew Gallo, Greg Arent or news content, see the listings below. National/State News Editor Editorial Editors Elan Ronen Copy Editors Maggie Schiller, Jeff Ruoss News Features Editor Brian Anderson, Catherine Brobston, Copy Desk Chiefs Brittany Talarico Kelly Durkin, Sarah Esralew, Jennifer Hayes, Jennifer Heine, Elisa Lala Display Advertising (302) 831-1398 Lauren DeZinno, Tucker Liszkiewicz Student Affairs News Editor ClassHied Advertising (302) 831-2771 Photography Editor Elena Chin Advertising Director Fax -

Concrete Crushing Can Continue

IN THIS WEEK’S EDITION COALER SPORTS $1.00 Partners honor Courant readers Vol. 119, Issue 43 1 section • 16 pages top volunteer pickdream team Not over 75% advertising www.coalcitycourant.com WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2020 | A FREE PRESS NEWSPAPER Superintendent search moving forward BY ANN GILL Should Exelon proceed with the “I THINK IT’S GOING TO BE A year and implement it with the 2022- are a lot of options for that, but those EDITOR intended closure of the Dresden 2023 school year, the first without are decisions that must be made by Generating Station in November TOUGH SITUATION FOR Bugg as the district’s leader. the seven-member board. The Unit 1 Board of Education 2021, the school district’s tax base will SOMEBODY TO BE HANDED THIS This is something that has the Under the leadership of presi- has made finding a superintendent to significantly shift. MENU AND FOR YOU TO SAY, superintendent concerned. dent Ken P. Miller, the Board of succeed Dr. Kent Bugg a priority. Property taxes paid by the power “You’re going to bring someone Education has been discussing the Bugg has 20 months left on his generator account for about 60% or ‘ALRIGHT THESE ARE THE THINGS new in the 22-23 school year that is various steps to finding a superin- final contract. While that might seem $16 million of the school district’s YOU HAVE TO DO.’ IF THERE IS A going to have to implement a plan tendent and has teamed with the like a considerable amount of time to more than $30 million budget. -

New Paltz Times Briefl Y Noted News of New Paltz, Highland, Gardiner Rosendale & Beyond

SPECIAL SECTION | HOME , LAWN & GARDEN GARDINER | CUPCAKE FEST MAY 20 HIGHLAND | SPRING FEST MAY 20 INSIDE 11 13 One dollar THURSDAY, MAY 18, 2017 www.hudsonvalleyone.com VOL. 17, ISSUE 20 New Paltz TimesTimes NEWS OF NEW PALTZ, GARDINER, HIGHLAND, ROSENDALE & BEYOND New Paltz voters Gearing up pass school budget, incumbent Steve Gabriella O’Shea and Hannah George speak Greenfi eld loses out about the dangers faced by bicyclists seat on the board to newcomers Kathy Preston and Teresa Thompson Teresa Thompson. Kathy Preston. HEN THE POLLS closed on Tuesday, May 16, New Paltz Central School Dis- W trict voters supported the proposed $59 million budget that comes with a 2.3 percent tax levy for the 2017-18 school year. There were 2,228 votes cast, out of which 1,561 votes were for the bud- get with just 667 opposed. The budget Continued on page 16 Highland district voters approve budget and bus proposition, two PHOTOS BY LAUREN THOMAS Gabby O’Shea and Hannah George on the Carmine Liberta Bridge on Route 299 in New Paltz. incumbent trustees to be sworn in again by Terence P Ward ABRIELLA O'SHEA STILL can't ride a bicycle on her own, but she's healed enough that she's ready to speak out about the dangers faced by anyone who pedals along the roads. When Hannah George fi rst started talking publicly about being hit by a car in March, her voice broke. Now it carries a steadiness that refl ects her determination to see bicycle safety treated as a top priority in New Paltz, Ulster County and beyond.