Resources for Ghost Boys IN-CLASS INTRODUCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources on Race, Racism, and How to Be an Anti-Racist Articles, Books, Podcasts, Movie Recommendations, and More

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” – JAMES BALDWIN DIVERSITY & INCLUSION ————— Resources on Race, Racism, and How to be an Anti-Racist Articles, Books, Podcasts, Movie Recommendations, and More Below is a non-exhaustive list of resources on race, anti-racism, and allyship. It includes resources for those who are negatively impacted by racism, as well as resources for those who want to practice anti-racism and support diverse individuals and communities. We acknowledge that there are many resources listed below, and many not captured here. If after reviewing these resources you notice gaps, please email [email protected] with your suggestions. We will continue to update these resources in the coming weeks and months. EXPLORE Anguish and Action by Barack Obama The National Museum of African American History and Culture’s web portal, Talking About Race, Becoming a Parent in the Age of Black Lives which is designed to help individuals, families, and Matter. Writing for The Atlantic, Clint Smith communities talk about racism, racial identity and examines how having children has pushed him the way these forces shape society to re-evaluate his place in the Black Lives Matter movement: “Our children have raised the stakes of Antiracism Project ― The Project offers participants this fight, while also shifting the calculus of how we ways to examine the crucial and persistent issue move within it” of racism Check in on Your Black Employees, Now by Tonya Russell ARTICLES 75 Things White People Can Do For Racial Justice First, Listen. -

Anti-Racism Resources

Anti-Racism Resources Prepared for and by: The First Church in Oberlin United Church of Christ Part I: Statements Why Black Lives Matter: Statement of the United Church of Christ Our faith's teachings tell us that each person is created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27) and therefore has intrinsic worth and value. So why when Jesus proclaimed good news to the poor, release to the jailed, sight to the blind, and freedom to the oppressed (Luke 4:16-19) did he not mention the rich, the prison-owners, the sighted and the oppressors? What conclusion are we to draw from this? Doesn't Jesus care about all lives? Black lives matter. This is an obvious truth in light of God's love for all God's children. But this has not been the experience for many in the U.S. In recent years, young black males were 21 times more likely to be shot dead by police than their white counterparts. Black women in crisis are often met with deadly force. Transgender people of color face greatly elevated negative outcomes in every area of life. When Black lives are systemically devalued by society, our outrage justifiably insists that attention be focused on Black lives. When a church claims boldly "Black Lives Matter" at this moment, it chooses to show up intentionally against all given societal values of supremacy and superiority or common-sense complacency. By insisting on the intrinsic worth of all human beings, Jesus models for us how God loves justly, and how his disciples can love publicly in a world of inequality. -

Mtv and Transatlantic Cold War Music Videos

102 MTV AND TRANSATLANTIC COLD WAR MUSIC VIDEOS WILLIAM M. KNOBLAUCH INTRODUCTION In 1986 Music Television (MTV) premiered “Peace Sells”, the latest video from American metal band Megadeth. In many ways, “Peace Sells” was a standard pro- motional video, full of lip-synching and head-banging. Yet the “Peace Sells” video had political overtones. It featured footage of protestors and police in riot gear; at one point, the camera draws back to reveal a teenager watching “Peace Sells” on MTV. His father enters the room, grabs the remote and exclaims “What is this garbage you’re watching? I want to watch the news.” He changes the channel to footage of U.S. President Ronald Reagan at the 1986 nuclear arms control summit in Reykjavik, Iceland. The son, perturbed, turns to his father, replies “this is the news,” and lips the channel back. Megadeth’s song accelerates, and the video re- turns to riot footage. The song ends by repeatedly asking, “Peace sells, but who’s buying?” It was a prescient question during a 1980s in which Cold War militarism and the nuclear arms race escalated to dangerous new highs.1 In the 1980s, MTV elevated music videos to a new cultural prominence. Of course, most music videos were not political.2 Yet, as “Peace Sells” suggests, dur- ing the 1980s—the decade of Reagan’s “Star Wars” program, the Soviet war in Afghanistan, and a robust nuclear arms race—music videos had the potential to relect political concerns. MTV’s founders, however, were so culturally conserva- tive that many were initially wary of playing African American artists; addition- ally, record labels were hesitant to put their top artists onto this new, risky chan- 1 American President Ronald Reagan had increased peace-time deicit defense spending substantially. -

Black Lives Matter Booklist 2020

Black Lives Matter Booklist Here are the books from our Black Lives Matter recommendation video along with further recommendations from RPL staff. Many of these books are available on Hoopla or Libby. For more recommendations or help with Libby, Hoopla, or Kanopy, please email: [email protected] Picture Books A is for Activist, by Innosanto Nagara The Undefeated, by Kwame Alexander & Kadir Nelson Hands Up! by Breanna J. McDanie & Shane W. Evans I, Too, Am America, by Langston Hughes & Bryan Collier The Breaking News, by Sarah Lynne Reul Hey Black Child, by Useni Eugene Perkins & Bryan Collier Come with Me, by Holly M. McGhee & Pascal Lemaitre Middle Grade A Good Kind of Trouble, by Lisa Moore Ramee New Kid, Jerry Craft The Only Black Girls in Town, Brandy Colbert Blended, Sharon M. Draper Ghost Boys, Jewell Parker Rhodes Teen Non-Fiction Say Her Name, by Zetto Elliott & Loveiswise Twelve Days in May, by Larry Dane Brimner Stamped, by Jason Reynolds & Ibram X. Kendi Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates This Book is Anti-Racist, by Tiffany Jewell & Aurelia Durand Teen Fiction Dear Martin, by Nic Stone All American Boys, by Jason Reynolds & Brendan Kiely Light it Up, by Kekla Magoon Tyler Johnson was Here, by Jay Coles I Am Alfonso Jones, by Tony Medina, Stacey Robinson & John Jennings Black Enough, edited by Ibi Zoboi I'm Not Dying with You Tonight, by Kimberly Jones & Gilly Segal Adult Memoirs All Boys Aren't Blue, by George M. Johnson When They Call You a Terrorist, by Patrisse Khan-Cullors & Asha Bandele Eloquent Rage, by Brittney Cooper I'm Still Here, Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness, by Austin Channing Brown How We Fight for Our Lives, by Saeed Jones Cuz, Danielle Allen This Will Be My Undoing, by Morgan Jerkins Adult Nonfiction Tears We Cannot Stop, by Michael Eric Dyson So You Want to Talk About Race, by Ijeoma Oluo White Fragility, by Robin Diangelo How To Be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. -

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020 1 7 Anti-Racist Books Recommended by Educators and Activists from the New York Magazine https://nymag.com/strategist/article/anti-racist-reading- list.html?utm_source=insta&utm_medium=s1&utm_campaign=strategist By The Editors of NY Magazine With protests across the country calling for systemic change and justice for the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade, many people are asking themselves what they can do to help. Joining protests and making donations to organizations like Know Your Rights Camp, the ACLU, or the National Bail Fund Network are good steps, but many anti-racist educators and activists say that to truly be anti-racist, we have to commit ourselves to the ongoing fight against racism — in the world and in us. To help you get started, we’ve compiled the following list of books suggested by anti-racist organizations, educators, and black- owned bookstores (which we recommend visiting online to purchase these books). They cover the history of racism in America, identifying white privilege, and looking at the intersection of racism and misogyny. We’ve also collected a list of recommended books to help parents raise anti-racist children here. Hard Conversations: Intro to Racism - Patti Digh's Strong Offer This is a month-long online seminar program hosted by authors, speakers, and social justice activists Patti Digh and Victor Lee Lewis, who was featured in the documentary film, The Color of Fear, with help from a community of people who want and are willing to help us understand the reality of racism by telling their stories and sharing their resources. -

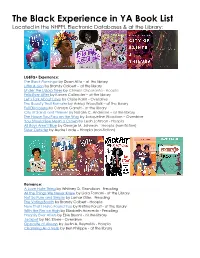

The Black Experience in YA Book List Located in the NHFPL Electronic Databases & at the Library

The Black Experience in YA Book List Located in the NHFPL Electronic Databases & at the Library: LGBTQ+ Experience: The Black Flamingo by Dean Atta – at the library Little & Lion by Brandy Colbert – at the library Under the Udala Trees by Chinelo Okparanta - Hoopla Felix Ever After by Kacen Callender – at the library Let’s Talk About Love by Claire Kann - Overdrive The Beauty That Remains by Ashley Woodfolk – at the library Full Disclosure by Camryn Garrett - at the library City of Saints and Thieves by Natalie C. Anderson – at the library The House You Pass on the Way by Jacqueline Woodson – Overdrive You Should See Me In a Crown by Leah Johnson - Hoopla All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson – Hoopla (non-fiction) Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde – Hoopla (non-fiction) Romance: A Love Hate Thing by Whitney D. Grandison - Freading All the Things We Never Knew by Liara Tamani - at the Library Not So Pure and Simple by Lamar Giles - Freading The Voting Booth by Brandy Colbert - Hoopla Now That I Have Found You by Kristina Forest - at the library With the Fire on High by Elizabeth Acevedo - Freading Happily Ever Afters by Elsie Bryant - at the library Jackpot by Nic Stone - Overdrive Opposite of Always by Justin A. Reynolds - Hoopla Charming As a Verb by Ben Philippe - at the library Fantasy & Sci-Fi: Pet by Akwaeke Emezi – at the library (LGBTQ+) Dread Nation by Justina Ireland - Freading (LGBTQ+) An Unkindness of Ghosts by Rivers Solomon - Hoopla (LGBTQ+) American Street by Ibi Zoboi – Freading A Song Below Water by Bethany C. -

DEAR MARTIN and DEAR JUSTYCE Photo © Nigel Livingstone

CLASSROOM UNIT FOR DEAR MARTIN AND DEAR JUSTYCE Photo © Nigel Livingstone RHTeachersLibrarians.com @RHCBEducators TheRandomSchoolHouse Justyce McAllister is top of his class and set for the Ivy League— but none of that matters to the police officer who just put him in handcuffs. And despite leaving his rough neighborhood behind, he can’t escape the scorn of his former peers or the ridicule of his new classmates. Justyce looks to the teachings of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. for answers. But do they hold up anymore? He starts a journal to Dr. King to find out. Then comes the day Justyce goes driving with his best friend, Manny, windows rolled down, music turned up— way up—sparking the fury of a white off-duty cop beside them. Words fly. Shots are fired. Justyce and Manny are caught in the crosshairs. In the media fallout, it’s Justyce who is under attack. Vernell LaQuan Banks and Justyce McAllister grew up a block apart in the southwest Atlanta neighborhood of Wynwood Heights. Years later, though, Justyce walks the illustrious halls of Yale University . and Quan sits behind bars at the Fulton Regional Youth Detention Center. Through a series of flashbacks, vignettes, and letters to Justyce—the protagonist of Dear Martin—Quan’s story takes form. Troubles at home and misunderstandings at school give rise to police encounters and tough decisions. But then there’s a dead cop and a weapon with Quan’s prints on it. What leads a bright kid down a road to a murder charge? Not even Quan is sure. -

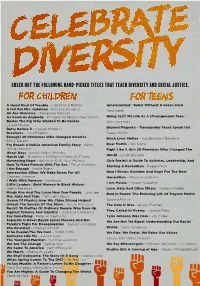

Check out the Following Hand-Picked Titles That Teach Diversity and Social Justice

Check out the following hand-picked titles that teach diversity and social justice. A Good Kind Of Trouble - Lisa Moore Ramee Americanized : Rebel Without A Green Card - A Hat For Mrs. Goldman - Michelle Edwards Sara Saedi All Are Welcome - Alexandra Penfold As Good As Anybody - Richard Michelson, Raul Colon Being Jazz: My Life As A (Transgender) Teen - Baxter The Pig Who Wanted To Be Kosher - Jazz Jennings Laurel Snyder Beyond Magenta - Transgender Teens Speak Out - Betty Before X - Ilyasah Shabazz Dreamers - Yuyi Morales Susan Kuklin - Enough! 20 Protesters Who Changed America Black Lives Matter - Sue Bradford Edwards Emily Easton Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story - Kevin Dear Martin - Nic Stone Noble Maillard Fight Like A Girl: 50 Feminists Who Changed The Ghost Boys - Jewell Parker Rhodes World - Laura Barcella Hands Up! - Breanna J. McDaniel Shane W. Evans Harvesting Hope - Kathleen Krull, Yuyi Morales Girls Resist!: A Guide To Activism, Leadership, And - Tanya Guerrero How To Make Friends With The Sea Starting A Revolution - Kaelyn Rich I Am Enough - Grace Byers Intersection Allies: We Make Room For All - How I Resist: Activism And Hope For The Next Chelsea Johnson Generation - Maureen Johnson I Walk With Vanessa - Kerascoët I Am Malala - Malala Yousafzai Little Leaders : Bold Women In Black History - Vashti Harrison Love, Hate And Other Filters - Samira Ahmed - Lyla Lee Mindy Kim And The Lunar New Year Parade Rest In Power: The Enduring Life Of Trayvon Martin - Mrs. Katz And Tush - Patricia Polacco Queen Of Physics: How Wu Chien Shiung Helped Sybrina Fulton Unlock The Secrets Of The Atom - Teresa Robeson The Hate U Give - Angie Thomas Resist: 35 Profiles Of Ordinary People Who Rose Up They Called Us Enemy - George Takei Against Tyranny And Injustice - Veronica Chambers Say Something - Peter H. -

To Be Black, Caribbean, and American

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2016 To Be Black, Caribbean, and American: Social Connectedness As a Mediator to Racial and Ethnic Socialization and Well-Being Among Afro-Caribbean American Emerging Adults Gihane Emeline Jeremie-Brink Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Counseling Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Jeremie-Brink, Gihane Emeline, "To Be Black, Caribbean, and American: Social Connectedness As a Mediator to Racial and Ethnic Socialization and Well-Being Among Afro-Caribbean American Emerging Adults" (2016). Dissertations. 2286. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2286 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2016 Gihane Emeline Jeremie-Brink LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO TO BE BLACK, CARIBBEAN, AND AMERICAN: SOCIAL CONNECTEDNESS AS A MEDIATOR TO RACIAL AND ETHNIC SOCIALIZATION AND WELL-BEING AMONG AFRO-CARIBBEAN AMERICAN EMERGING ADULTS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN COUNSELING PSYCHOLOGY BY GIHANE E. JÉRÉMIE-BRINK CHICAGO, IL DECEMBER 2016 Copyright by Gihane E. Jérémie-Brink, 2016 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank God, for God’s grace, faithfulness, and tender mercies throughout my life. I would not be here today without the love and sacrifices of my wonderful parents, Dutroy and Yves Emeline Jérémie. -

1. Christ the Servant 2. the Christian As a Servant 3. Serving As Leadership 4. Love, Humility, Gifting. 5. Humbling and Servant

1. Christ the Servant 2. The Christian as a Servant 3. Serving as Leadership 4. Love, humility, gifting. 5. Humbling and servanthood www.legana.org Christ, The Servant LEADER’S NOTES This is a practical Bible Study series. The result of this series should be increased acts of service toward brothers and sisters in Christ, and a willingness to serve in the world. The essence of a Christ-changed life is humility. The fruit of humility is servanthood. In this series we will explore how serving: honours God, reflects Jesus Christ, blesses others, matures believers, evangelises and disciples. We will see that serving costs. It requires humility. It requires sacrifice. It may lead to being misunderstood. It will lead to being unthanked and unappreciated. When we consider the humblest servant of all, Jesus Christ, He was despised, mocked and rejected. Serving can be hard. Christian service is different to mere humanitarian service. The Scriptures teach that God empowers our service- we can serve in His strength. Added to this, God places within the Church those who have the spiritual gift to serve. By seeking God and His strength, the believer is able to do more than they otherwise could. This then becomes a powerful witness because it causes observers to wonder how it is possible. The answer of course leads to God being glorified. Thus, when a believer refuses to stretch in their serving, they are in part depriving God of glory. The questions in this Bible Study series are designed to help lead your group in exploring what the Bible actually says about servanthood; why it might be saying this; and how we can apply those Texts which instruct us in our serving. -

Black Voices Summer 2020.Indd

BLACK VOICES2020 is newsletter features books by contemporary Black authors, across all genres and ages. It is not an exhaustive list, but you will nd both individually highlighted books and lists with more authors and titles to discover. Be sure to visit each author’s website to learn more about them. The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead An American Marriage by Tayari Jones Elwood Curtis is about to enroll in the local black college. But for a black boy in Newlyweds Celestial and Roy are the embodiment of the American Dream. But the Jim Crow South of the early 1960s, one innocent mistake lands him in a juve- as they settle into their life together, Roy is sentenced to twelve years for a crime nile reformatory called the Nickel Academy. In reality, the Academy is a grotesque Celestial knows he didn’t commit. Unmoored, Celestial takes comfort in her friend chamber of horrors where the sadistic staff beats and sexually abuses the students. Andre, and becomes unable to hold on to the love that has been her center as Roy’s More books to check out by two-time Pulitzer Prize winning Colson Whitehead in- time in prison passes. But after fi ve years, Roy’s conviction is suddenly overturned, clude The Underground Railroad, The Noble Hustle, Zone One, Sag Harbor, Apex and he returns to Atlanta ready to resume their life together. Also check out Jones’ Hides the Hurt, John Henry Days, and The Intuitionist. Anchor $15.95. books Silver Sparrow, The Untelling, and Leaving Atlanta. Algonquin $16.95. -

A Reading List for Adults, Teens, and Youth

A READING LIST FOR ADULTS, TEENS, AND YOUTH. ADULTS Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Penguin Random House Publisher In a profound work that pivots from the biggest questions about American history and ideals to the most intimate concerns of a father for his son, Ta-Nehisi Coates offers a powerful new framework for understanding our nation’s history and current crisis. Americans have built an empire on the idea of “race,” a falsehood that damages us all but falls most heavily on the bodies of black women and men—bodies exploited through slavery and segregation, and, today, threatened, locked up, and murdered out of all proportion. What is it like to inhabit a black body and find a way to live within it? And how can we all honestly reckon with this fraught history and free ourselves from its burden? Stamped From the Beginning by Ibram X. Kendi, Bold Type Books Some Americans insist that we're living in a post-racial society. But racist thought is not just alive and well in America--it is more sophisticated and more insidious than ever. And as award-winning historian Ibram X. Kendi argues, racist ideas have a long and lingering history, one in which nearly every great American thinker is complicit. How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi, One World Publisher Antiracism is a transformative concept that reorients and reenergizes the conversation about racism—and, even more fundamentally, points us toward liberating new ways of thinking about ourselves and each other. At its core, racism is a powerful system that creates false hierarchies of human value; its warped logic extends beyond race, from the way we regard people of different ethnicities or skin colors to the way we treat people of different sexes, gender identities, and body types.